The public health paradox of wildfire smoke

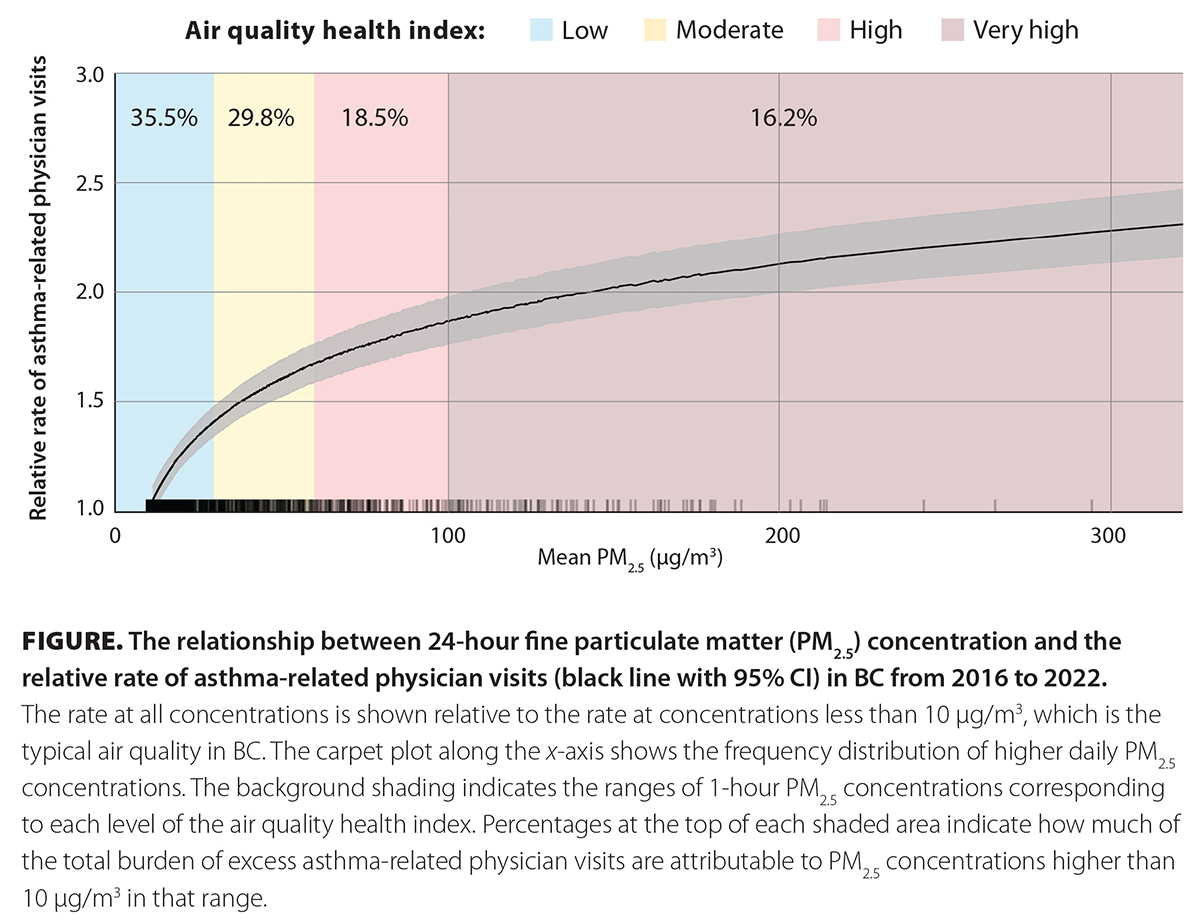

When the BCCDC presents on the public health impacts of wildfire smoke, we often ask audiences to consider the following question: If there are 10 asthma-related physician visits on a slightly smoky day, how many occur on a day with 10 times as much smoke? Based on epidemiologic evidence, the answer is about 20 [Figure]. Based on human intuition, however, the most common response is 100. This is true even among professionals who are trained in environmental public health.

When the BCCDC presents on the public health impacts of wildfire smoke, we often ask audiences to consider the following question: If there are 10 asthma-related physician visits on a slightly smoky day, how many occur on a day with 10 times as much smoke? Based on epidemiologic evidence, the answer is about 20 [Figure]. Based on human intuition, however, the most common response is 100. This is true even among professionals who are trained in environmental public health.

Wildfire smoke is a complex mixture of gases and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), all of which can affect health.[1] However, concentrations of PM2.5 are typically used as a proxy for the whole mixture, for a few reasons. First, PM2.5 is the ambient air pollutant most consistently elevated by wildfire smoke. Second, PM2.5 is widely measured by regulatory and community science air-quality monitoring networks. Third, decades of research have demonstrated that PM2.5 exposure is harmful to respiratory, cardiovascular, endocrine, brain, and reproductive health.[2]

Despite human intuition, the relationship between PM2.5 concentrations and acute respiratory outcomes is nonlinear, with steeper slopes at lower concentrations and a plateau at higher concentrations [Figure]. The same pattern has been described for long-term PM2.5 exposure and the development of cardiovascular disease.[3] This nonlinear concentration-response relationship is likely due to biological saturation of the cellular processes that cause health harms at high PM2.5 concentrations.[4]

Here lies the public health paradox: wildfire smoke gets a lot of public and media attention when PM2.5 concentrations are extreme, but it causes much more harm at the lower concentrations that occur more frequently. In BC, concentrations over 100 µg/m3 are responsible for less than 20% of asthma-related visits attributable to wildfire smoke. However, more than 35% occur at concentrations between 10 and 30 µg/m3 [Figure].

The climate in BC is changing, and wildfire smoke is starting to dominate our lifetime exposure to air pollution.[5] As with all other types of air pollution, reducing exposure to wildfire smoke will reduce the associated health risks. If we focus our attention on the extreme events and ignore the more moderate impacts, we miss most of our opportunity to protect health. We should collectively start to manage exposures whenever wildfire smoke is affecting air quality.

Most people spend the majority of their time indoors, so cleaner indoor air should be the primary focus. Large buildings need smoke-readiness plans, while commercial and DIY air cleaners are effective for homes and smaller spaces.[6] If we combine cleaner indoor air with other simple strategies such as taking it easy outdoors and wearing respiratory protection when appropriate, we can reduce the short- and long-term health impacts of wildfire smoke.

—Sarah B. Henderson, PhD

Scientific Director, BCCDC Environmental Health Services

—Phuong D.M. Nguyen, BSc

Research Assistant, BCCDC Environmental Health Services

—Jiayun Angela Yao, PhD

Senior Scientist, BCCDC Environmental Health Services

—Michael J. Lee, PhD

Environmental Epidemiologist, BCCDC Environmental Health Services

hidden

This article is the opinion of the BC Centre for Disease Control and has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Reisen F, Duran SM, Flannigan M, et al. Wildfire smoke and public health risk. Int J Wildland Fire 2015;24:1029-1044.

2. Feng S, Gao D, Liao F, et al. The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2016;128:67-74.

3. Smith KR, Peel JL. Mind the gap. Environ Health Perspect 2010;118:1643-1645.

4. Thangavel P, Park D, Lee YC. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2.5)-mediated toxicity in humans: An overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:7511.

5. Burke M, Childs ML, de la Cuesta B, et al. The contribution of wildfire to PM2.5 trends in the USA. Nature 2023;622:761-766.

6. Barn PK, Elliott CT, Allen RW, et al. Portable air cleaners should be at the forefront of the public health response to landscape fire smoke. Environ Health 2016;15:116.