COVID-19 fatalities among long-term care residents in the Vancouver Coastal Health region

ABSTRACT

Background: Advanced age and chronic comorbidities were established as important risk factors of severe illness early in the COVID-19 pandemic. We examined COVID case fatality rates among long-term care residents in the Vancouver Coastal Health region to reveal the scale and temporal patterns of fatalities during the initial waves of local disease transmission during the pandemic.

Methods: Data were obtained from Vancouver Coastal Health surveillance records and the British Columbia Vital Statistics Agency, spanning 12 January 2020 to 25 June 2022. The fatality rate of long-term care residents within the Vancouver Coastal Health region who were COVID-positive was measured across six phases of the pandemic. “COVID-19-related” and “30-day all-cause” case fatality variables were used, and data were stratified by time period and age group.

Results: In total, 3418 COVID cases were included. The COVID-related fatality rate among long-term care residents declined from wave 1 (34.3%) to wave 6 (1.9%); the overall fatality rate was 9.9%. The overall 30-day all-cause case fatality rate also declined from wave 1 (32.9%) to wave 6 (6.0%), with an overall 30-day all-cause case fatality rate of 13.6%.

Conclusions: The significant reduction in COVID-related fatality rates among long-term care residents in the Vancouver Coastal Health region in association with vaccination uptake and effectiveness, hybrid immunity, and changing viral strains emphasizes the critical role of timely vaccinations in safeguarding vulnerable populations.

Continued efforts to enhance vaccination coverage and monitor emerging viral strains are essential to mitigate the impact of novel communicable diseases on long-term care residents.

Background

Understanding of SARS-CoV-2 infection has evolved considerably since the virus was first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. However, advanced age, in particular among those with chronic comorbidities, was established as an important risk factor for severe illness and mortality early in the COVID-19 pandemic.[1] Canadian data indicate that although individuals 70 years of age and older have accounted for only 14% of all reported COVID cases, they represent more than 80% of all COVID-related deaths.[2]

In British Columbia, long-term care facilities provide care to individuals with complex health needs, who often require 24-hour professional supervision and help with most or all daily activities.[3] Seventy-five long-term care facilities provide care in the Vancouver Coastal Health region, which serves 1.25 million people. The facilities are located in the Howe Sound, North Shore, Sunshine Coast, and Central Coast regions, as well as the cities of Vancouver and Richmond.[4] Thirty-five (47%) are operated by the health authority; 40 (53%) are operated by nongovernmental and other organizations, mostly not-for-profits.[5]

SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of long-term care facilities was associated with the rapid spread of infection and devastating mortality. The first outbreak in a long-term care facility in Canada was reported in the Vancouver Coastal Health region. Thus, early in the pandemic, resource-intensive and intrusive interventions were implemented in long-term care facilities to prevent the importation of the virus and limit its spread. This included daily screening of staff and residents, cancellation of group recreation activities, limitation of in-person visitation by family and friends to exceptional situations only, and isolation of ill residents and exposed contacts (usually the rest of the unit) for prolonged periods.[6] Despite these measures, a study by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) indicated that in 2020, Canada had the highest mortality of long-term care residents compared with community-dwelling older persons in 12 OECD member countries.[7]

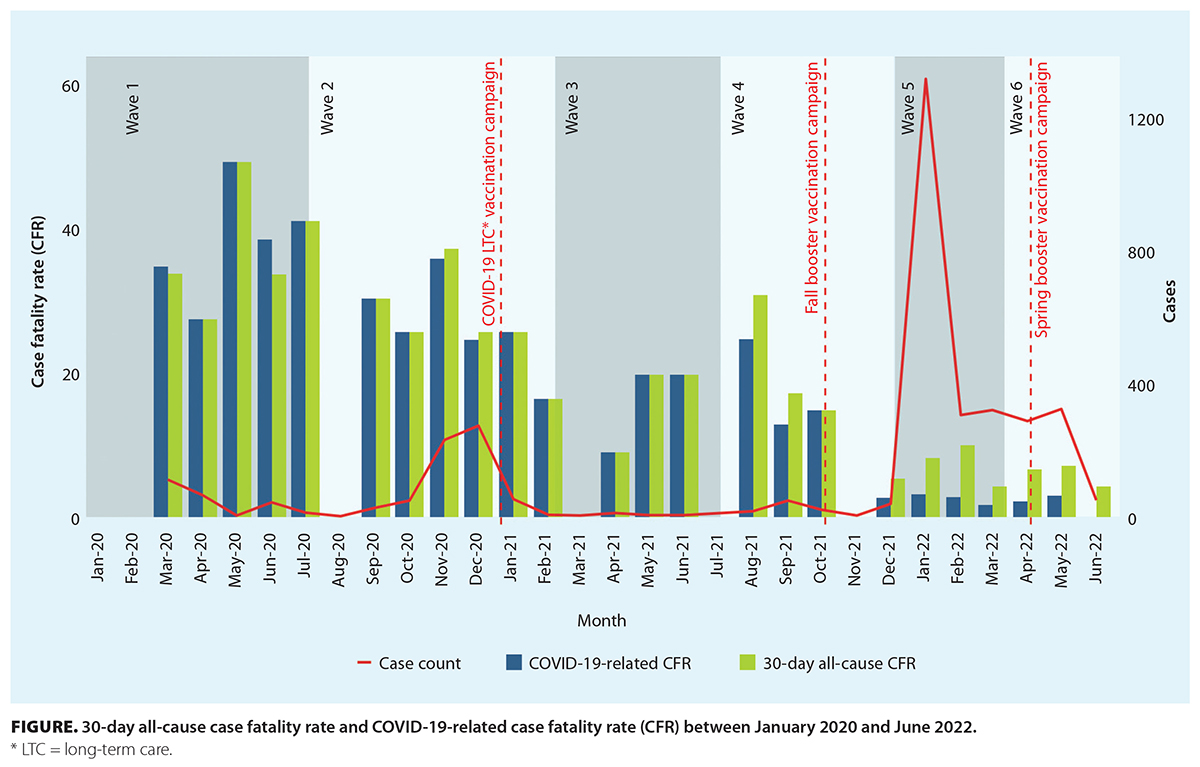

Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were first approved by Health Canada on 9 December 2020, less than 1 year after the novel virus was first identified. An immunization campaign began in BC on 15 December 2020, with long-term care staff among the first group eligible to be immunized. Immunization of long-term care residents began 1 week later, corresponding with permission to move the vaccine from central holding points.[8] This was followed by several cycles of immunization campaigns to complete the primary two-dose series in long-term care facilities by spring 2021, and booster campaigns were implemented biannually starting in fall 2021. The highly changeable nature of SARS-CoV-2 led to waves of illness activity in the community and in long-term care facilities. Though the illness experience among long-term care residents evolved in 2021, the most dramatic shift was noted with the arrival of the Omicron wave in December 2021.[9]

We examined COVID case and case fatality data among long-term care residents in the Vancouver Coastal Health region from the beginning of the COVID pandemic to June 2022 to reveal the scale of COVID case fatality among those residents and examine temporal patterns of fatalities across each wave of local disease transmission.

Methods

Study design

Case and mortality data were obtained from Vancouver Coastal Health Public Health surveillance records spanning 12 January 2020 to 25 June 2022. For the purpose of sensitivity analysis, mortality data were also obtained through linkage with the BC Centre for Disease Control’s Public Health Reporting Data Warehouse (PHRDW), which includes several data sources, such as BC Vital Statistics.[10] The PHRDW collates information from data sources across BC and provides it to public health partners for real-time surveillance activities,[10] though there is some delay in complete capture of all deaths. Data for this study were accessed on 5 July 2023, and we had access to identifiable information on residents during and after data collection.

We performed a retrospective analysis of all cases of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 among long-term care residents within the Vancouver Coastal Health region by measuring crude fatality rate across six phases of the pandemic. Long-term care facilities reported all cases of COVID infection of residents to Vancouver Coastal Health Public Health daily. The reports were updated to include case outcomes, such as hospitalization and death, as they occurred. The reported mortality data were supplemented with a data linkage between case reports and all resident deaths reported administratively to Vancouver Coastal Health. During waves 1 and 2 of the pandemic, from 12 January 2020 to 6 February 2021, all deaths of COVID-positive patients in long-term care facilities were attributed to their COVID infection and thus were deemed COVID related. Beginning during wave 3 (7 February 2021 to 3 July 2021) and onward through wave 6 (13 March 2022 to 25 June 2022), Vancouver Coastal Health medical health officers reviewed any death of long-term care residents to determine the causal relationship with preceding infection. This produced a binary “COVID-19-related fatality” variable: “yes” indicated that the death was determined to be due to COVID; “no” indicated the death was determined to have occurred following an active COVID infection but was deemed to not be due to the infection.

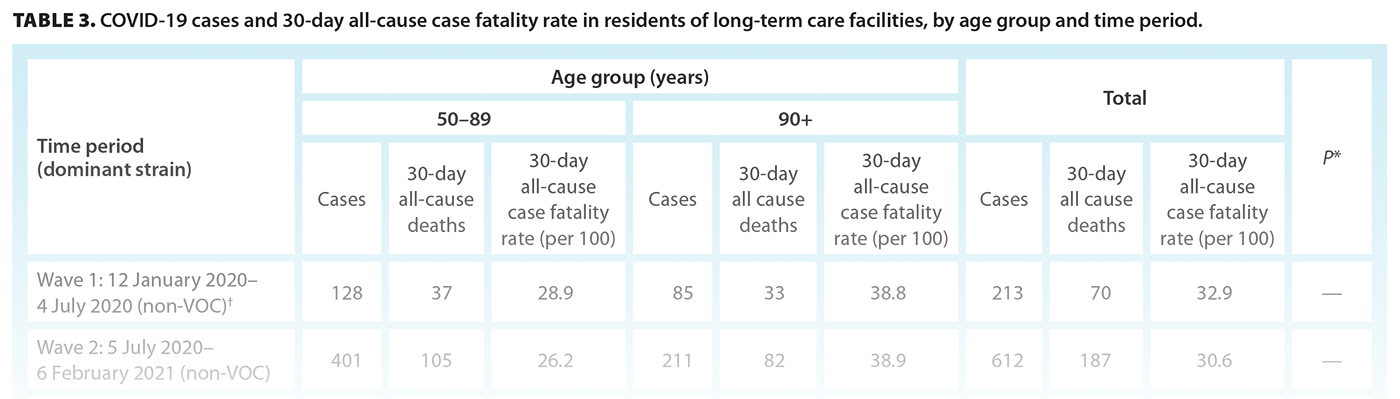

We also examined deaths due to any cause in COVID-infected individuals within 30 days of the collection of their positive specimen. Where the date of specimen collection was not known, symptom onset date was used, based on the more comprehensive PHRDW data linkage. The “30-day all-cause case fatality” variable was applied to all COVID cases in the study population: “yes” indicated the death had occurred within 30 days of the specimen collection or onset date; “no” indicated otherwise.

Analysis

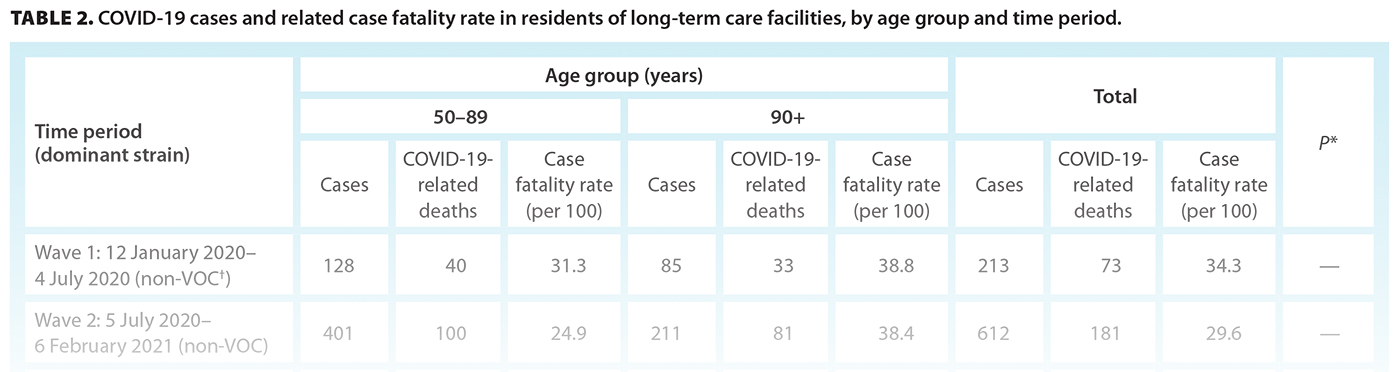

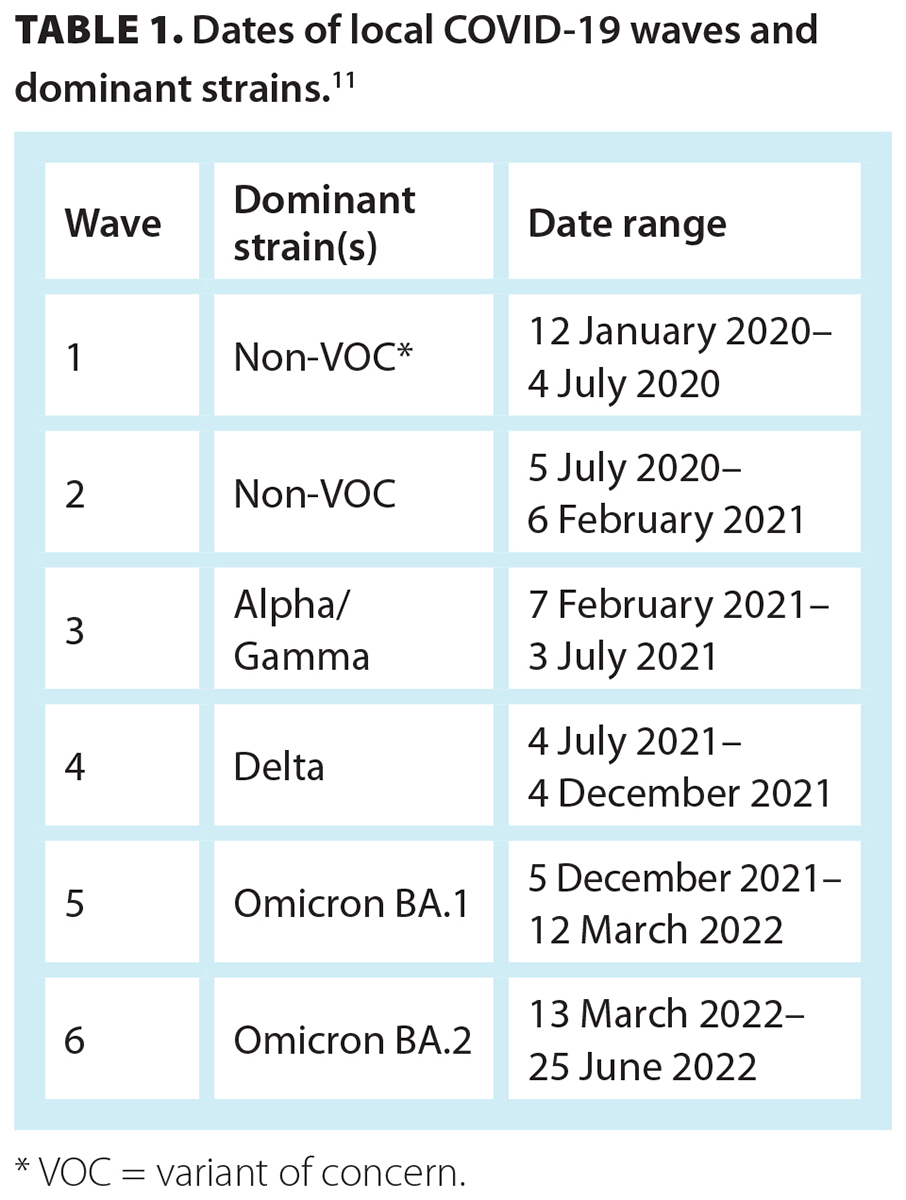

We performed two separate analyses to compare fatality rates using the COVID-19-related and 30-day all-cause fatality variables. Data were stratified by age group and time period. Age groups were divided into residents who were 50 to 89 years of age and those who were 90 years of age or older. To ensure confidentiality, residents who were younger than 50 years of age were excluded from the analysis due to the small sample size. Time periods were based on the dominant viral strain that was circulating among the local population [Table 1].[11] Date ranges of each pandemic phase, or wave, were informed by the epidemic curve of COVID cases known among the BC population, as well as local circulation within the Vancouver Coastal Health region.[11] Genomic sequencing data from the BC Centre for Disease Control’s Public Health Laboratory were used to determine the dominant viral strains that were most prevalent during each wave. The Mann-Kendall trend test was used to determine trends across the waves of the pandemic. All analyses were conducted using R, version 4.3.1.[12] Study-specific ethics approval was waived by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board, because public health surveillance is within the mandate of the local medical health officer under the provisions of BC’s Public Health Act.

We performed two separate analyses to compare fatality rates using the COVID-19-related and 30-day all-cause fatality variables. Data were stratified by age group and time period. Age groups were divided into residents who were 50 to 89 years of age and those who were 90 years of age or older. To ensure confidentiality, residents who were younger than 50 years of age were excluded from the analysis due to the small sample size. Time periods were based on the dominant viral strain that was circulating among the local population [Table 1].[11] Date ranges of each pandemic phase, or wave, were informed by the epidemic curve of COVID cases known among the BC population, as well as local circulation within the Vancouver Coastal Health region.[11] Genomic sequencing data from the BC Centre for Disease Control’s Public Health Laboratory were used to determine the dominant viral strains that were most prevalent during each wave. The Mann-Kendall trend test was used to determine trends across the waves of the pandemic. All analyses were conducted using R, version 4.3.1.[12] Study-specific ethics approval was waived by the University of British Columbia’s Research Ethics Board, because public health surveillance is within the mandate of the local medical health officer under the provisions of BC’s Public Health Act.

Results

In total, 3545 cases of COVID-19 infection in Vancouver Coastal Health long-term care facilities were identified by laboratory testing between 12 January 2020 and 25 June 2022. During this period, 127 cases (3.6%) were excluded from the analysis because the individuals were under 50 years of age at diagnosis. Individuals between 50 and 89 years of age represented 64.0% (n = 2189) and those 90 years of age and older represented 35.2% (n = 1202) of the total 3418 cases included in the analysis [Table 2]. The highest overall caseload in long-term care occurred during wave 5, between 5 December 2021 and 12 March 2022 (n = 1675, 49.0%). However, the highest overall number of deaths in long-term care residents occurred during wave 2, between 5 July 2020 and 6 February 2021 (n = 181, 53.6%).

In total, 3545 cases of COVID-19 infection in Vancouver Coastal Health long-term care facilities were identified by laboratory testing between 12 January 2020 and 25 June 2022. During this period, 127 cases (3.6%) were excluded from the analysis because the individuals were under 50 years of age at diagnosis. Individuals between 50 and 89 years of age represented 64.0% (n = 2189) and those 90 years of age and older represented 35.2% (n = 1202) of the total 3418 cases included in the analysis [Table 2]. The highest overall caseload in long-term care occurred during wave 5, between 5 December 2021 and 12 March 2022 (n = 1675, 49.0%). However, the highest overall number of deaths in long-term care residents occurred during wave 2, between 5 July 2020 and 6 February 2021 (n = 181, 53.6%).

The COVID-19-related case fatality rate across waves 1 to 6 was 9.9% (n = 338) [Table 2]. Even though the rate during wave 4 increased by 4.0 percentage points over that of wave 3, there was a statistically significant decrease from 34.3% during wave 1 to 1.9% during wave 6 (P < .001). Vaccines were first introduced in long-term care facilities in December 2020, near the end of wave 2 [Figure]. Second doses were given to long-term care residents with a minimum interval of 28 days from the first dose. By the end of the spring 2021 immunization campaign, 97% of long-term care residents had received at least one dose of the vaccine, and 92% had received two doses.

The overall 30-day all-cause case fatality rate across waves 1 to 6 was 13.6% (n = 464) [Table 3]. The rate during wave 4 increased by 7.5 percentage points over that of wave 3, but overall, there was a statistically significant decrease from 32.9% during wave 1 to 6.0% during wave 6 (P < .001).

Discussion

Between 12 January 2020 and 25 June 2022, the overall case fatality rate in residents of long-term care facilities in the Vancouver Coastal Health region was 13.6% based on the 30-day all-cause fatality variable and 9.9% based on the COVID-19-related case fatality variable. Based on all data available from the beginning of the COVID pandemic to September 2023, the Public Health Agency of Canada reported a case fatality rate of 1.5% across all age groups in BC, 1.5% for individuals between 50 and 89 years of age, and 8.5% for persons 90 years of age and older.[2] Though caution should be used in making comparisons with these results due to different variable definitions and time periods used, our data indicate a disproportionate impact of COVID on residents of long-term care facilities in the Vancouver Coastal Health region.

The evaluation of COVID-19-related case fatality rates in long-term care facilities in our study indicated that the original virus, or non–variant of concern strain of SARS-CoV-2, was associated with a 30% to 34% case fatality rate among residents. The rate declined to 11% during the Alpha/Gamma wave (wave 3), which was likely a result of both the protective effect of the primary series of COVID vaccines and changes in the virulence of the circulating strain. The protective effect of the COVID vaccines on hospitalization and mortality rates is well documented.[7,13-16] In addition, several biannual booster campaigns have been implemented since the original primary series was offered, all of which have included long-term care residents. The Delta variant (wave 4) was associated with increased transmissibility compared with previous variants and significant mortality of community-dwelling adults in jurisdictions that did not have access to vaccines;[17] in our local context, the COVID-19-related case fatality rate among long-term care residents increased to 15.1%, and the 30-day all-cause case fatality rate increased to 18.6%.

The arrival of the Omicron variant (wave 5) was notable, because it was characterized by high transmissibility and vaccine immune evasion. Infection-acquired seroprevalence among Canadians rose rapidly to 76% in the latter half of 2022 in association with the introduction of the Omicron BA.1 and BA.2 variants.[18] However, there was a significant reduction in the severity of illness following infection with the Omicron variant compared with the Delta variant.[19,20] Though the seroprevalence of infection-induced antibodies remained lowest among individuals 60 years of age and older in the general population (less than 60%) in March 2023,[18] and though it was likely higher among long-term care residents given their congregated living arrangement, our results support the attenuated severity of the Omicron variant, given that the lowest case fatality rate in long-term care residents occurred in waves 5 and 6. The 30-day all-cause case fatality rate was 8.4% and 6.0%, respectively, while the COVID-19-related case fatality rate was 3.2% and 1.9%, respectively.

Overall, our results underscore the importance of timely vaccination efforts to protect long-term care residents, especially given their heightened vulnerability to severe outcomes due to both age and comorbidities. Our data also suggest that public health monitoring of viral strains and their associated transmissibility and severity will remain important for determining nuanced public health interventions that are proportionate to time, geography, and population-specific risk. Long-term care facilities faced highly restrictive policies during the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a number of documented negative effects, including physical health consequences, reduced nutrition, increased physical pain, loneliness, depressive symptoms, agitation, aggression, and reduced cognitive ability.[21,22] Because long-term care facilities are homes for frail individuals, creating a balance between managing the risks posed by an emerging virus and the unintended harms of pandemic control restrictions on quality of life for residents is recommended. This is a crucial assessment that should be built into pandemic plans and should consider emerging information and advances in prevention and control, including the availability of vaccines and treatment. Studies from BC and Canada provide suggestions for future mitigation of risk within long-term care facilities.[23,24]

Study limitations

Our study may have been limited by an incomplete case ascertainment and underreporting of deaths among long-term care residents. Given that the systematic review of COVID-19 case fatality in long-term care facilities was implemented only at the beginning of the third wave of the pandemic, it is possible that COVID-related fatality was overreported during the first two waves. Nevertheless, due to early implementation of twice-a-day symptom-based surveillance, low-threshold testing of symptomatic individuals, close care coordination between Vancouver Coastal Health Public Health and facilities regarding case management, and heightened vigilance within long-term care facilities, it is unlikely that incomplete case ascertainment or underreporting/overreporting was a significant factor during the first 2 years of the pandemic. Given the rapid increase in infections following the arrival of the Omicron variant, it is possible that individuals with mild infection may not have been tested or reported. Seroprevalence studies identified a large prevalence of asymptomatic infections, though clinical relevance of those infections beyond provision of infection-acquired immunity is unclear.

The probability that deaths were not reported is low, though this remains a source of concern when interpreting trends in fatality rates. We compensated for this by calculating both the COVID-19-related case fatality rate and the 30-day all-cause case fatality rate, the latter of which provided the upper bounds of severity of COVID-related illness in facilities. Long-term care residents are frail individuals with complex underlying health conditions. The 30-day all-cause case fatality rate during waves 5 and 6 approximated a return to baseline fatality from other natural causes and at worst was an outer estimate for case fatality rate due to COVID. In total, 168 deaths during waves 5 and 6 that were not reported in real time by long-term care facilities were detected using the retrospective 30-day analysis. Given the close and frequent collaboration between the Office of the Chief Medical Health Officer and the long-term care sector, including daily to weekly contact with facilities that were experiencing illness, we are reasonably confident that if those deaths had been attributed to COVID, they would have been reported to the Office of the Chief Medical Health Officer for further review. Additionally, the trend in our reported COVID-19-related case fatality rate was consistent with the trend observed by the neighboring Fraser Health Authority through its surveillance (personal communication, Dr Jing Hu, 26 October 2023). An internal review of long-term care licensing data across the Vancouver Coastal Health region indicated that the yearly mortality rate in long-term care facilities in 2022 was 18.7%, lower than the 2019 prepandemic rate of 22.6%, which further indicates a return to baseline fatality from all causes within long-term care facilities by the time pandemic precautions had been lifted. Finally, the relatively small sample size in our study precluded further subanalyses involving other covariates related to COVID-19 case fatality, though they have been examined in the literature.[25-27]

Conclusions

The introduction of vaccines and the changing viral landscape significantly influenced case fatality rates in long-term care facilities in the Vancouver Coastal Health region, which emphasizes the critical role of vaccinations in safeguarding vulnerable populations. Continued efforts to enhance vaccination coverage and monitor emerging viral strains are essential to mitigating the impact of novel communicable diseases on long-term care residents. Such strategies are crucial to ensure the well-being and safety of this population during ongoing and future public health challenges.

Competing interests

Dr Schwandt is a member of the BCMJ Editorial Board but did not participate in the review or decision-making process.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Mueller AL, McNamara MS, Sinclair DA. Why does COVID-19 disproportionately affect older people? Aging (Albany, NY) 2020;12:9959-9981. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103344.

2. Public Health Agency of Canada. COVID-19 daily epidemiology update: Summary. 2021. Accessed 3 October 2023. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/.

3. BC Ministry of Health. Long-term care services. 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/accessing-health-care/home-community-care/care-options-and-cost/long-term-care-services.

4. Vancouver Coastal Health. Long-term care. 2023. Accessed 10 October 2023. www.vch.ca/en/health-topics/long-term-care.

5. Vancouver Coastal Health. VCH LTC matrix. 2022. Accessed 10 October 2023. www.vch.ca/en/media/20441.

6. Baker R. Relaxed visiting rules take effect at B.C. long-term care facilities. CBC News. 1 April 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-ltc-visitor-rules-1.5972310.

7. Sepulveda ER, Stall NM, Sinha SK. A comparison of COVID-19 mortality rates among long-term care residents in 12 OECD countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21:1572-1574.E3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.08.039.

8. Health Canada. Health Canada authorizes first COVID-19 vaccine. 2020. Accessed 10 October 2023. www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/news/2020/12/health-canada-authorizes-first-covid-19-vaccine0.html.

9. COVID-19 Immunity Task Force. Seroprevalence in Canada. Accessed 12 November 2023. www.covid19immunitytaskforce.ca/seroprevalence-in-canada/.

10. BC Centre for Disease Control. Data and analytic services. 2023. Accessed 2 February 2024. www.bccdc.ca/our-services/service-areas/data-analytic-services.

11. BC Centre for Disease Control. Respiratory surveillance: Genomic surveillance. 2023. Accessed 14 November 2023. https://bccdc.shinyapps.io/genomic_surveillance.

12. R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2021. Accessed 10 October 2023. https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/fullrefman.pdf.

13. Wright BJ, Tideman S, Diaz GA, et al. Comparative vaccine effectiveness against severe COVID-19 over time in US hospital administrative data: A case-control study. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:557-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(22)00042-X.

14. de Gier B, van Asten L, Boere TM, et al. Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on mortality by COVID-19 and on mortality by other causes, the Netherlands, January 2021–January 2022. Vaccine 2023;41:4488-4496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2023.06.005.

15. Steele MK, Couture A, Reed C, et al. Estimated number of COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths prevented among vaccinated persons in the US, December 2020 to September 2021. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2220385-e2220385. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.20385.

16. Wu N, Joyal-Desmarais K, Ribeiro PAB, et al. Long-term effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against infections, hospitalisations, and mortality in adults: Findings from a rapid living systematic evidence synthesis and meta-analysis up to December, 2022. Lancet Respir Med 2023;11:439-452. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-2600(23)00015-2.

17. Atherstone CJ, Guagliardo SAJ, Hawksworth A, et al. COVID-19 epidemiology during Delta variant dominance period in 45 high-income countries, 2020–2021. Emerg Infect Dis 2023;29:1757-1764. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2909.230142.

18. Murphy TJ, Swail H, Jain J, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in Canada: A time-series study, 2020–2023. CMAJ 2023;195:E1030-E1037. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.230249.

19. Kow CS, Ramachandram DS, Hasan SS. The risk of mortality and severe illness in patients infected with the Omicron variant relative to Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ir J Med Sci 2023;192:2897-2904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-03266-6.

20. Jassat W, Abdool Karim SS, Ozougwu L, et al. Trends in cases, hospitalizations, and mortality related to the Omicron BA.4/BA.5 subvariants in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2023;76:1468-1475. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac921.

21. Hugelius K, Harada N, Marutani M. Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2021;121:104000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104000.

22. Liu M, Maxwell CJ, Armstrong P, et al. COVID-19 in long-term care homes in Ontario and British Columbia. CMAJ 2020;192:E1540-E1546. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.201860.

23. Yau B, Vijh R, Prairie J, et al. Lived experiences of frontline workers and leaders during COVID-19 outbreaks in long-term care: A qualitative study. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:978-984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2021.03.006.

24. Vijh R, Prairie J, Otterstatter MC, et al. Evaluation of a multisectoral intervention to mitigate the risk of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission in long-term care facilities. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021;42:1181-1188. https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2020.1407.

25. Dessie ZG, Zewotir T. Mortality-related risk factors of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 42 studies and 423,117 patients. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:855. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06536-3.

26. Flook M, Jackson C, Vasileiou E, et al. Informing the public health response to COVID-19: A systematic review of risk factors for disease, severity, and mortality. BMC Infect Dis 2021;21:342. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-05992-1.

27. Booth A, Reed AB, Ponzo S, et al. Population risk factors for severe disease and mortality in COVID-19: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021;16:e0247461. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247461.

All authors work in the Office of the Chief Medical Health Officer, Vancouver Coastal Health. Ms Moustaqim-Barrette is an epidemiologist; Mr Ramler is a public health information analyst; Mr St-Jean is an epidemiologist; Dr Daly is the chief medical health officer and vice-president, public health; Dr Hayden is a medical health officer; Dr Lysyshyn is the deputy chief medical health officer; Dr Schwandt is a medical health officer; Ms MacDonald is the regional director, public health surveillance unit; and Dr Dawar is a medical health officer.