Dr David A. Haughton: From ER to studio

Dr Haughton traded his stethoscope for a paint brush, and now signs his emails, “Sincerely, David the Painter.”

|

| David Haughton in his New Westminster home studio. |

A black-and-white photo shot at the end of his final night shift in the emergency department speaks volumes. Sitting on a gurney, arms crossed, grinning ear to ear, Dr David Haughton has a face that confidently says, “I did it!”

BC Children’s Hospital emergency physician Dr David A. Haughton took the plunge and dove into painting as of 7:30 a.m. on 29 October 2017. And once he plunged, he wasted no time. He gave away his medical equipment and textbooks, took a few things off the wall, and left the hospital with a box containing just a few items—including his stethoscope in case he needed to check his blood pressure. The next day he canceled his medical licence and CMPA insurance and stopped practising as a physician.

The move wasn’t a surprise. Haughton had been an artist for 40 years and a physician for 32. His plan all along had been to become successful enough as an artist, in parallel to medicine, to eventually become an artist full time.

Haughton applied the same boundless passion and dedication to medicine as he does to his art. He was an exceptional medical leader, mentor, and teacher who presided over the Section of Emergency Medicine for 11 years. Mr Rob Hulyk, director of Physician Advocacy at Doctors of BC, considers Haughton to have been the association’s most persistent and effective section head. He was regularly spotted at the association’s West Broadway offices perched at a window seat in the staff lounge, with a view of the North Shore mountains, working on his laptop. It has taken three co-presidents to fill Haughton’s extraordinary shoes as section head, divvying up the large portfolio and leading its 500 members and 23 executive members. The Section of Emergency Medicine established an award in Haughton’s name to honor his leadership legacy—his trademark style of enthusiasm, integrity, honesty, and respect. His exemplary collegial interactions with patients and peers, his visionary leadership, and his strategic orientation did not go unnoticed.

Medical practice

Haughton chose emergency medicine deliberately. Few other specialties include no call, no pager, scheduled shifts, and the flexibility to work part-time. The freedom of an emergency medicine physician working 36 hours a week is vastly different from an orthopedic surgeon or pediatrician taking calls a few nights a week and managing a busy practice. He gradually discovered he enjoyed working night shifts—working 3 or 4 nights in a row was easier than working the occasional night. Emergency medicine allowed him to care for children, yet separate himself from the ongoing needs of his young patients, freeing up time for nonclinical activities.

Experiences from Haughton’s early medical training became an unforeseen source of inspiration for his first series of figurative paintings, Kindertotentanz, depicting his sense of ambivalence toward modern medicine while working as a pediatric resident in the mid-’80s. Feelings of disturbance, anger, and helplessness compelled Haughton to paint critically ill and deformed children and babies fighting for their lives. “When the doctors and parents pursued the hope of newer medicines, more aggressive modalities, combinations of treatments; when the children bled, grew feverish, or gasped for breath, I did what I could. Often, the attending doctors were unavailable, jostling in administrative meetings or presenting new research proposals. The mothers held their dying children, facing the reality of the diseases.” In this series Haughton felt that he was advocating for the children and for their parents’ anguish over their children’s pointless pain.[1]

While Haughton was glad to make proper diagnoses as a physician, he says the real joy came from interactions with the kids who showed up in the ER. With a big smile Haughton recalls the many times he played games with a 6-month-old or a 2-, 5-, or 15-year-old who arrived in the ER scared to death. Checking for a child’s reaction to him acting goofy was useful as a diagnostic tool to rule out meningitis. By playing with the kids, he managed to get them laughing, sometimes laughing at him, or just giggling, providing priceless moments of delight.

|

| Dr David Haughton’s last shift at the BC Children’s Hospital emergency department. |

Artistic practice

The top floor of Haughton’s New Westminster home has been his studio since 1995. A bright, cozy, inviting space, located under the eaves, packed with art, painting supplies, and books on his masters, all largely self-taught like him: Cézanne, Homer, van Gogh, and Goya. In ninth grade, he stumbled across his Japanese 17th-century “artist super hero,” Katsushika Hokusai, famed for The Great Wave, who created his best work in his 90s. Hokusai has provided an artistic compass and inspires Haughton to this day. Hokusai’s artistic ethos, the beauty and simplicity of his images, and the ferocious enthusiasm with which he worked as an artist until his old age all captivate Haughton’s imagination.

Travel and painting have always been intertwined for Haughton, both before and after he became a physician. In 1975 he spent a year in Greece and began mastering pen-and-ink drawings of landscapes and monasteries using a drafting pen with no pre-sketching or notation. For a dozen years he worked almost exclusively in pen and ink before moving to watercolors.

While a physician, he dedicated up to 2 months a year to painting. For the last decade, Haughton and his wife, Dr Lyne Filiatrault, have retreated to remote Tofino during storm season, which inspired a series entitled Fear, Hope and Longing. Painting this series helped him face and express the anxiety related to aging and the looming end of his medical career. In his 2016 art newsletter he wrote, “Lately I’m inspired by an intense feeling of personal vulnerability and evanescence. Perhaps it is that I am perched on the seam between two tectonic plates in temporary equipoise, awaiting the slip, the earthquake, the tsunami. Perhaps it is that I am on the edge of leaving a secure income for a life of full-time painting. More likely: I am 60 years old.”[2]

Haughton’s artistic process for landscapes starts with capturing the scene. Usually with his digital camera close by or clipped to his belt, he takes photographs, sometimes several dozen different shots—close-ups, at a distance, panoramas, and so on. Then, back in his studio—days, months, or even years later—with photographs displayed, he imagines himself there again, and starts a painting with a pencil sketch. He currently has about 200 paintings in different states of completion.

His landscape paintings are much more than pretty images; they are his emotional response. In his paintings Haughton tries to capture his initial, immediate emotional and intellectual reaction. He hopes it triggers the viewer in a similar way, and maybe even sets their heart aflutter.

Fully immersed in art

Today Haughton the artist paints in acrylics exclusively and has developed a unique painting style. Superficially, his landscapes might look like a Group of Seven or Impressionist painting. However, his painterly technique is totally different. First, he paints on multimedia artboard on a flat surface, not on canvas on an easel. He’s never come across an artist who uses artboard in combination with acrylics the way he does. “It’s my own and it’s new. Nobody else has done it,” he says. What he’s referring to is his technique that gives his paintings a jewel-like depth, achieved by layering and glazing three or four times to pop the color. He likens it to transparent sheets of very thin glass.

Now fully immersed in his art, Haughton doesn’t think about medicine the way he used to. However, between brushstrokes, his wife will not allow him to forget his medical past. Dr Filiatrault, also a retired emergency medicine physician, has shifted into medical administration, leading VGH’s Medical Staff Association. She brings home stories that remind him that while he misses his medical colleagues, he does not miss the politics of medicine.

Haughton’s brilliant leadership skills have a new application. Not only is he now a full-time artist, he is also a gallerist, working to keep a not-for-profit Seattle gallery alive. He says the learning curve to becoming a gallerist is steep and completely different than being an artist, but he’s enjoying it. “The whole bandwidth that was involved in the politics of medicine is now involved in the politics of the art world,” he says.

“To quote Frank Sinatra,” says Haughton, “What I’m most proud of is that I did it my way. I feel enormously happy and content that I had the courage to make the jump.”

Haughton’s art can be viewed at www.haughton-art.ca.

|

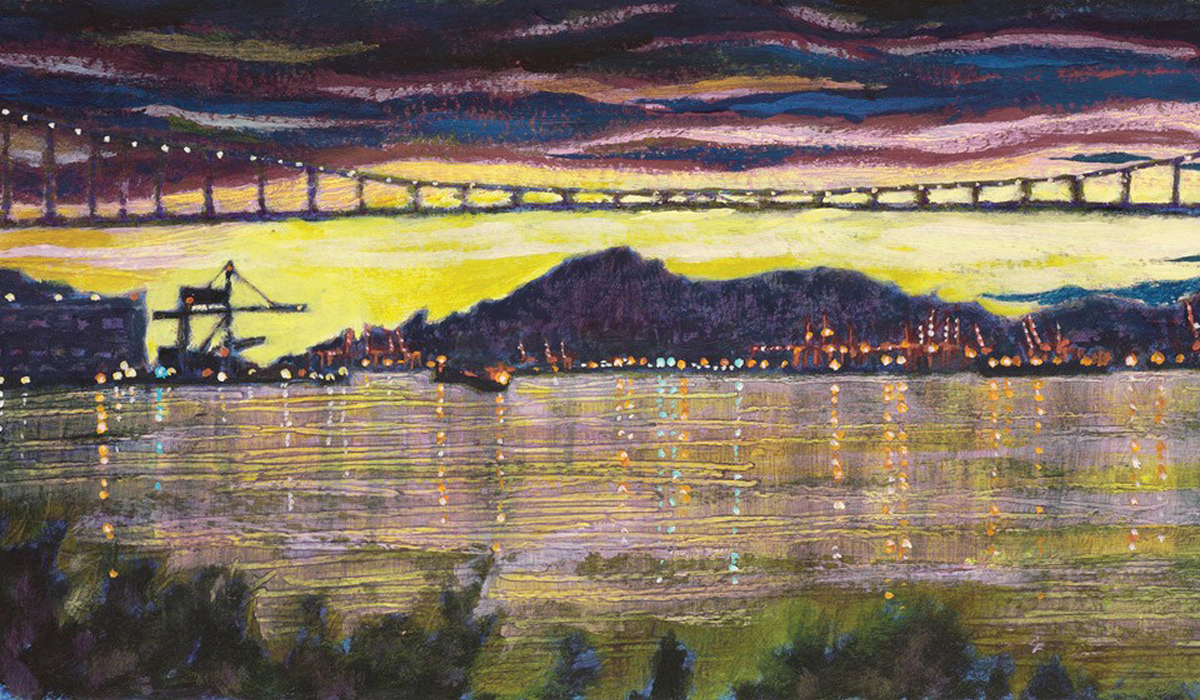

| Before Dawn IV—Under the Bridge by David Haughton. Acrylic on multimedia artboard, 2015. |

hidden

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

1. Fraser JL. Articulating the unthinkable. CMAJ 2009;181:E173-E174.

2. Haughton DA. Invitation to fear, hope & longing. Artist website. Accessed 26 October 2018. www.haughton-art.ca/invitation-to-fear-hope-and-longing-iii.

hidden

Ms Lynch-Staunton has worked as a sections coordinator with Doctors of BC since 2000.