Traditional medicines and healing practices

When I entered medical school almost 20 years ago, topics about Indigenous people (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit) were put under the umbrella of Indigenous health. The topics focused on health disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, social determinants of health, and harms caused by culturally unsafe care and discrimination. As outlined in one of my previous editorials,[1] these topics are less about Indigenous people and more about the impacts of colonialism and racism that Indigenous people have endured. The logical questions that follow are: What is Indigenous health, and how can we advance it?

Indigenous health is defined by Indigenous people; is rooted in their traditional ways of knowing, being, and healing; and it outlines their own pathways to wellness. Each Nation will have unique health-related values tied to its traditions, lands, and laws. Cultural and traditional wellness practices provide the foundation for Indigenous health. This is why the ability to access and use traditional medicines and practices is outlined as a fundamental right in article 24 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Call to Action #22. With this foundation, Indigenous communities can augment their traditional healing practices with best practices from Western medicine to lead clinical research, education, and services that are designed for them, by them. This is commonly referred to as a Two-Eyed-Seeing approach, originally coined by Mi'kmaw Elder Albert Marshall, and is used to describe the use of both knowledge systems to ensure the best possible outcomes for Indigenous people.

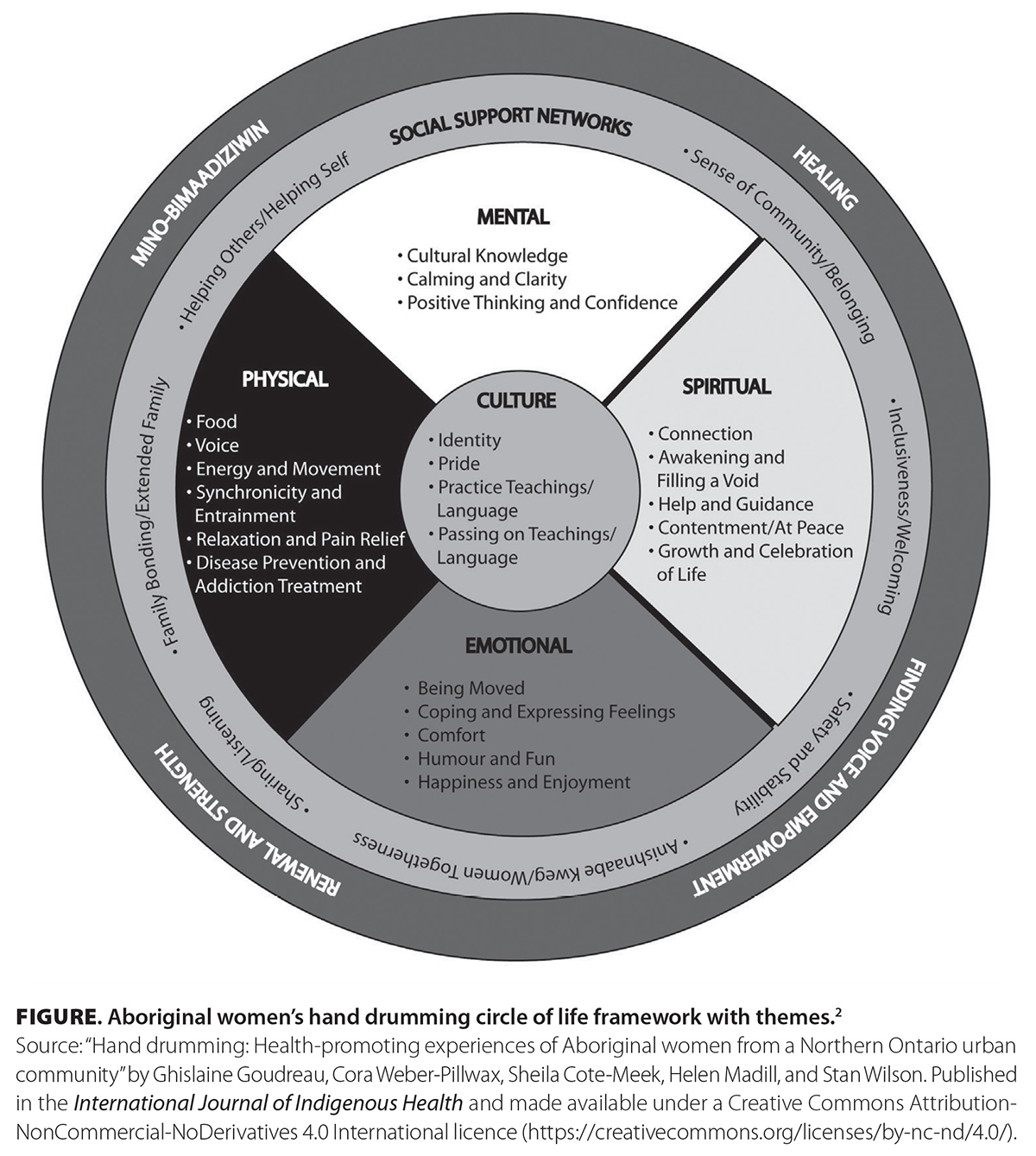

There are many Indigenous models of health, with the medicine wheel being a well-known holistic health model attributed to Plains Nations. The model has many teachings, and I’ll highlight just a few of them. My favorite concept of the medicine wheel [Figure] has culture in the centre, depicting the importance of culture for our health and healing.[2] The next ring of the circle depicts that the health of a person has four elements: physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. This is like the biopsychosocial model taught from a Western lens. Our Elders would teach that each part of the medicine wheel impacts the other parts, and that to restore health, we need to find balance. The outer circles reflect that an individual’s health is influenced by the health of their families, their communities, and all of creation. This is rooted in the belief that we are all connected, and we need to maintain respectful relationships for all to thrive.

There are many Indigenous models of health, with the medicine wheel being a well-known holistic health model attributed to Plains Nations. The model has many teachings, and I’ll highlight just a few of them. My favorite concept of the medicine wheel [Figure] has culture in the centre, depicting the importance of culture for our health and healing.[2] The next ring of the circle depicts that the health of a person has four elements: physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual. This is like the biopsychosocial model taught from a Western lens. Our Elders would teach that each part of the medicine wheel impacts the other parts, and that to restore health, we need to find balance. The outer circles reflect that an individual’s health is influenced by the health of their families, their communities, and all of creation. This is rooted in the belief that we are all connected, and we need to maintain respectful relationships for all to thrive.

The beliefs and practices that help to restore health vary widely among different Indigenous groups and Nations; however, knowing a few key differences can be helpful for health care providers. The two main categories of traditional wellness are traditional medicines and traditional healing practices. Traditional medicines are medicinal herbs, teas, and salves derived from plants and animals that are harvested and prepared for treatment of specific ailments. Traditional healing practices can include ceremonies, energy work, physical practices (e.g., massage), and counseling. These practices vary widely; however, they all work by attuning all aspects of a person’s medicine wheel. Of note, most traditional approaches to health focus on prevention and include teachings about the importance of nutrition, fasting, activity, and ceremony to help guide people to live long, healthy lives in balance with the world around them. As physicians, being curious and open to discuss how and if Indigenous people are using traditional medicines and practices is a key component to cultural safety; however, it is important not to assume that all Indigenous people use or would want to use these methods of healing and not to misappropriate these teachings.

As we find ourselves deep in the winter months, I reflect that this is the time of year during which many northern Indigenous people would enter months of relative solitude in our winter camps. We would often co-locate in smaller family groups and take advantage of the shorter days to rest, pass on our oral histories, create art, build and repair items, and hold ceremonies. The other seasons were quite labor intensive from harvesting and collecting food and raw materials, as well as from larger social gatherings and traveling around the territory. Although the winter months posed a significant threat to our survival from exposure to the elements and a lack of food, it became a crucial time for rest and rejuvenation.

In our fast-moving world, where we are often out of sync with the natural cycle of growth and rest, it is important to remember that rest is crucial. Constant growth and harvesting of ourselves and the world lead to depletion and is not sustainable. I hope you can take time to attune to your medicine wheel in preparation for the tumultuous seasons ahead.

—Terri Aldred, MD

hidden

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Aldred T. Indigeneity is healing. BCMJ 2024;66:73.

2. Goudreau G, Weber-Pillwax C, Cote-Meek S, et al. Hand drumming: Health-promoting experiences of Aboriginal women from a Northern Ontario urban community. Int J Indig Health 2008;4. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijih41200812317.