Requiem for a program

In 1982 a group of clinicians and scientists in the UBC Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology began offering in vitro fertilization services at UBC Hospital. IVF was in its infancy in North America, and no “made in Canada” IVF pregnancy had been achieved. After some months of unsuccessful attempts, the program shifted to Shaughnessy Hospital where, in the summer of 1983, success was finally achieved. Robby Reid, Canada’s first “test-tube baby,” was born at Vancouver’s Grace Maternity Hospital on 25 December 1983—premature, but healthy.

Having an IVF program in British Columbia was a blessing for many women and their partners, but public opinion remained mixed. The first few pregnancies were slow to arrive, and the IVF process was labor intensive, requiring (as it did then) a laparoscopy under general anesthesia to retrieve eggs from the ovaries. The waiting list ballooned to 2 years. Fortunately, after some years the need for laparoscopy and general anesthesia disappeared, as transvaginal egg retrieval under conscious sedation became the norm.

The costs of treatment for the first few years were, to a large extent, offset by coverage from the Ministry of Health, but in 1988 the Vander Zalm provincial government de-insured IVF treatment. Thereafter, the costs of IVF treatment in British Columbia became the direct responsibility of patients. Requests to restore insurance coverage for IVF treatment were rejected on the grounds that such treatment was “experimental.” Many couples went into debt to pay for their single attempt at IVF, and only a minority returned for a second attempt.

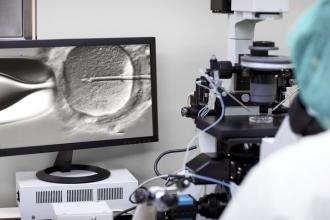

In 1992 the provincial government announced plans to close Shaughnessy Hospital, and a new home for the IVF program was found in Vancouver General Hospital’s Willow Pavilion. Gradually, new techniques such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection, egg donation, and blastocyst culture became incorporated in treatment options, and as the new millennium dawned global IVF pregnancy rates took an upward leap, just in time to meet the demographic shift in the age of women attempting pregnancy for the first time.

The first 20 years of the IVF program were celebrated at a remarkable gathering at the Vancouver Aquarium in 2003. At that celebration, it was acknowledged that the costs of IVF treatment remained beyond the reach of many in British Columbia, and the Hope Fertility Fund was established to provide grants for IVF treatment to those who needed it. The first donation to the fund came from Robby Reid’s mother.

Additional IVF programs in the province gave women and couples more options for IVF treatment, but a core population seemed most comfortable with a program that was based in an institution. However, in 2006 VGH revised its patient footprint, and the UBC IVF Program faced eviction once more. Further negotiations heralded a return to the Shaughnessy Hospital site, by now transformed into BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. The program’s members then had their first experience of working in an area designed specifically for reproductive technology.

A happy couple of years later, UBC’s Faculty of Medicine elected to divest itself of all clinical programs, and the IVF Program (being a not-for-profit entity) had to find a new sponsor. The administration of BC Women’s agreed to take over the program, and did so in late 2010. But the new era did not last. The old building in which the IVF Program was housed was creaking, and renovations in the vicinity of the program began in March 2012, necessitating temporary closure of assisted reproduction activities for fear of contamination. Further audit by the hospital of the aging equipment in the program’s gamete laboratory showed the need for multiple upgrades, the costs of which were considerably beyond the hospital’s budget.

And so the administration elected to close the IVF program.

I don’t wish to revisit this decision: it is what it is. However, I can lament the loss of a BC institution, one which over almost 30 years generated previously unimagined happiness for thousands of families in British Columbia. I can lament the fact that Canada has lost a trailblazing program. I can lament the fact that there is no longer an institution-based, not-for-profit IVF program option for the province. But I can also take comfort in knowing that UBC IVF was a wonderful program that was conceived in exciting times, yielded substantial scientific output, and provided generous service to the people of British Columbia for a long time. I will miss it.

—TCR