I recently came across a Medscape Medical News item from July 2020 about a medical student’s complaint, on Twitter, about an inappropriate description of Cushing disease in a popular textbook, Dr Pestana’s Surgery Notes, printed in 2020. According to the textbook, the effect of the disease was to turn a “lovely young woman” into a “monster.” If she did not have Cushing disease, then she was just a “fat hairy lady.” The textbook’s publisher apologized for the sexist description of this patient and pledged to correct future editions of the book.

I thought, well done, observant student! Then the topic of Cushing disease took me back 66 years to my fourth year of medical school. My professor of neurology very respectfully introduced my small clinical group to a 40-year-old woman with a symptom complex of weight gain, distorted facial features, hirsutism, fatty tissue deposits between the shoulders, and thinning and fragile skin. The patient had Cushing disease.

I remember the professor explaining that a similar symptom complex was first mentioned by Dr William Osler in 1898, but at that time the condition was not understood. The concept of “hormones” was just emerging and Osler thought his patient suffered from myxedema, then a popular term for those with what today we call hypothyroidism. It was Dr Harvey Cushing who eventually discovered that patients experiencing similar symptomology would have either a pituitary tumor or an adrenal gland tumor on autopsy.

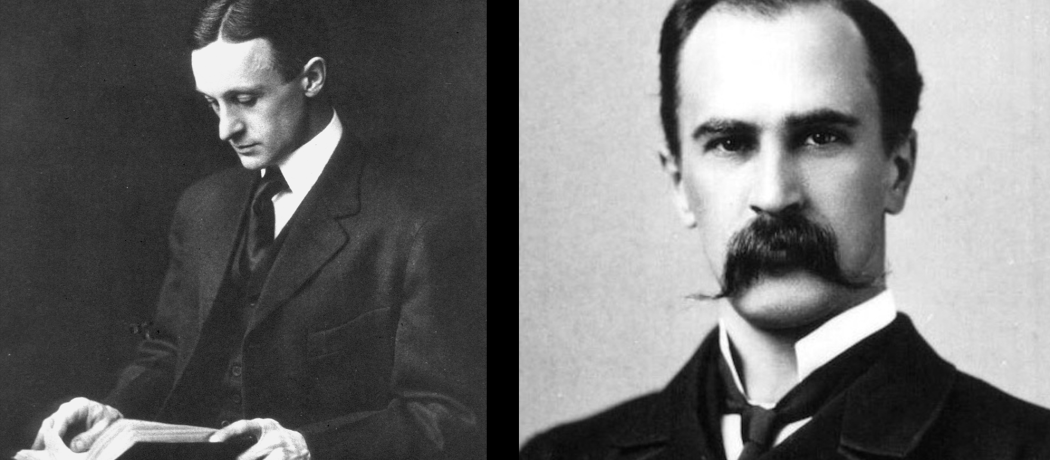

I have not thought of Cushing disease since that clinical session ages ago, but with my memory now stirred, I wanted to know more about the disease, Dr Cushing’s work, and his possible connection to Dr Osler. I looked up the specifics of Cushing disease and Cushing syndrome and was fascinated to learn that William Osler (1849–1919) was a mentor of Harvey Williams Cushing (1869–1939) when they worked at the Johns Hopkins Hospital between 1896 and 1912.

Osler’s interest in neurosciences dated back to 1884 when he studied the brain of a seal. He was in close association with clinical neurologists of the time. At Johns Hopkins Hospital he conducted close to 1000 human autopsies with a focus on localization of brain function. Around the same time, Cushing studied general surgery at Johns Hopkins Hospital with William Stewart Halstead (1852–1927), a famous surgeon who insisted on using new aseptic operating room techniques and championed emerging anesthetic procedures. Neurosurgery in those days was a discouraging field, and Halsted thought Cushing should not move in that direction. But Cushing energetically advanced operative techniques that significantly reduced death rates linked with brain surgery. He became an expert in the diagnosis and treatment of intracranial tumors, including pituitary tumors, which eventually led him to identify the etiology of what today we call Cushing disease.

A deep friendship developed between Osler and Cushing, even though they were of different temperaments. Osler was a great educator, a humanist, and had what descriptions suggest was a joyful way of life. His emphasis on crucial appraisal of research evidence and focus on the patient was the forerunner of our current evidence-based medicine. He was also critical in a friendly way about Cushing’s occasional rudeness with students and members of the staff (though patients thought of Cushing as a very humane physician).

Cushing’s health declined in the last 20 years of his life. He had circulatory problems in his legs related to his heavy smoking habit. He was ill with the flu during the 1918–1919 pandemic and later developed symptoms of Guillain-Barré syndrome, which interfered with his finger movements during his surgical work. In 1925 he produced Osler’s biography, which was honored with a Pulitzer Prize. His extraordinarily productive medical life came to an end in 1939. He died of an acute myocardial infarction.

I wish we had a time machine to meet these two giants of medicine.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

Suggested reading

Bliss M. Harvey Cushing: A life in surgery. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005.

Bliss M. William Osler: A life in medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

Cushing H. William Osler, the man. Ann Med Hist 1919;2:157-167.

da Mota Gomes M. William Osler and Harvey Williams Cushing: Friendship around neurosurgery. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2019;22:384-388.

Mock J. Sexist description in surgical textbook highlights bias in medicine, physicians say. Medscape Medical News. 1 July 2020. Accessed 28 March 2022. www.medscape.com/viewarticle/933264.

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |