Management of tick bites and tick-borne diseases in British Columbia

Ticks are known vectors for transmission of tick-borne diseases in British Columbia. Tick bites and concern about tick-borne diseases are common presenting complaints to primary care and urgent care settings, especially during warmer months.[1] This article aims to inform clinicians about the ticks most commonly encountered in BC and the diseases they may transmit to humans.

Ticks and tick-borne diseases in BC

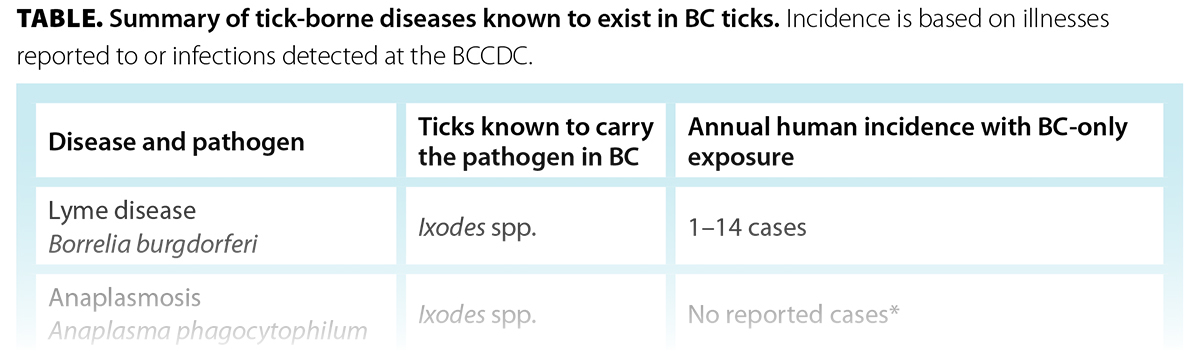

The prevalence of ticks and tick-borne diseases varies by geography.[2] In BC, Ixodes pacificus and Ixodes angustus ticks are predominant in the southern coastal regions, while Dermacentor andersoni are more common in the Interior and Northern regions.[1] Ixodes ticks are capable of transmitting Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma phagocytophilum, and Babesia spp., while Dermacentor ticks are associated with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, tularemia, and tick paralysis [Table].[3]

Management of tick bites

Ticks found on patients should be removed promptly using forceps. Although the vast majority of tick bites in BC do not result in illness, patients should be advised to look for early symptoms of tick-borne diseases, such as fever, rash, fatigue, and aches. A localized rash within the first 48 hours after a tick bite is more likely to be a local reaction to the bite rather than an infection. While antibiotic post-exposure prophylaxis for Lyme disease may be indicated following a tick bite in geographic regions with high prevalence of B. burgdorferi, it is not usually required for tick exposures originating in BC due to the low prevalence (typically < 1%) of B. burgdorferi in BC ticks.[1,4,5] In comparison, highly endemic areas in central and eastern Canada have tick positivity rates greater than 20%.[6] The main reason for this difference is that Ixodes scapularis, found in eastern North America, is a more efficient carrier of B. burgdorferi compared with Ixodes pacificus, which is the predominant vector in BC.[7]

Photos of ticks may also be submitted for free by providers or patients to eTick (www.etick.ca), a public platform for image-based identification of ticks. They will identify the tick species and inform users about pathogens the tick may carry. Clinicians can also send ticks to the BCCDC Public Health Laboratory for free identification and pathogen analysis.[8]

Management of tick-borne diseases

If symptoms develop following a tick bite, clinical features and laboratory test results can guide diagnostic assessment and empiric treatment. Lab confirmation should be sought to determine the suspected cause of illness. Information about laboratory tests available at the Public Health Laboratory can be found at www.elabhandbook.info.

—Jae Ford, MD, MPH

Resident Physician, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, UBC

—Quinn Stewart, MPH

Epidemiologist, BCCDC

—Stefan Iwasawa

Vector Specialist, BCCDC

—Muhammad Morshed, PhD

Clinical Microbiologist, BCCDC Public Health Laboratory, Vancouver

—Mayank Singal, MD, MPH, CCFP, FRCPC

Public Health Physician, BCCDC

hidden

This article is the opinion of the BC Centre for Disease Control and has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Provincial Health Services Authority, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control. Ticks and tick-borne disease surveillance in British Columbia. 2023. Accessed 7 February 2024. www.bccdc.ca/Documents/Ticks_and_Tick-Borne_Disease_Surveillance%20_BC.pdf.

2. Elmieh N., National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health. A review of ticks in Canada and health risks from exposure. 2022. Accessed 7 February 2024. https://ncceh.ca/resources/evidence-reviews/review-ticks-canada-and-health-risks-exposure.

3. Washington State Department of Health. Tick-borne diseases. Accessed 13 March 2024. https://doh.wa.gov/you-and-your-family/illness-and-disease-z/tick-borne-diseases.

4. Morshed MG, Lee MK, Boyd E, et al. Passive tick surveillance and detection of Borrelia species in ticks from British Columbia, Canada: 2002–2018. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2021;21:490-497.

5. Centre for Effective Practice. Early Lyme disease management in primary care. 2020. Accessed 7 February 2024. https://cep.health/media/uploaded/CEP_EarlyLymeDisease_Provider_2020.pdf.

6. Guillot C, Badcock J, Clow K, et al. Sentinel surveillance of Lyme disease risk in Canada, 2019: Results from the first year of the Canadian Lyme Sentinel Network (CaLSeN). Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46:354-361.

7. Couper LI, Yang Y, Yang XF, Swei A. Comparative vector competence of North American Lyme disease vectors. Parasit Vectors 2020;13:29.

8. BC Centre for Disease Control Public Health Laboratory. Parasitology requisition. Accessed 7 February 2024. www.bccdc.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Guidelines%20and%20Forms/Forms/Labs/ParaReq.pdf.