Taking serious illness conversations seriously: Unveiling South Asian perspectives on advance care planning using the Serious Illness Conversation Guide

ABSTRACT

Background: Advance care planning and advance directives help patients define goals of care in case of incapacity or end-of-life situations and thus improve quality of life and reduce unnecessary treatments. The Serious Illness Conversation Guide facilitates these discussions, though cultural beliefs influence patients’ values and decisions.

Methods: We used a qualitative study to explore the South Asian community’s understanding of advance care planning and advance directives using the Serious Illness Conversation Guide. Eighteen English-speaking South Asian adults participated in focus groups and a survey.

Results: Participants identified three key themes regarding discussions of advance care planning and advance directives in the South Asian community: generational differences in the willingness to engage in such discussions, the role of family members in making health care decisions, and the power differential between patients and health care providers. Recommendations were made for providing culturally appropriate phrasing in the Serious Illness Conversation Guide.

Conclusions: Cultural awareness is needed in advance care planning and advance directives discussions with South Asian Canadians. Clinicians should consider acculturation levels and adapt language to improve engagement, particularly for older adults and new immigrants. Further research should explore strategies for enhancing access to advance care planning and advance directives in diverse communities.

Clinicians should consider acculturation levels and adapt language to improve engagement in advance care planning and advance directives discussions with South Asian Canadians, particularly older adults and new immigrants.

Background

Advance care planning and advance directives involve discussions with patients and their families about their values, goals, and beliefs in advance of incapacity or when faced with end-of-life care. These early discussions in palliative care can improve the patient’s quality of life, reduce aggressive interventions, and improve family and caregiver outcomes.[1-3]

Numerous factors, including cultural, social, and personal beliefs, can significantly impact the effectiveness and outcomes of advance care planning and advance directives discussions. Given the deeply personal nature of these conversations, it is crucial to consider the cultural context in which they occur.[4] Culture includes one’s beliefs, ideas, and customs that are shared within an individual’s community.[4] The importance of cultural knowledge when having these discussions is invaluable due to the sensitive and important nature of advance care planning and advance directives. Cultural influences are particularly significant for communities transitioning to Western countries that have different cultural perspectives, as evidenced in the South Asian diaspora. Conflicts may arise as these individuals try to balance their traditional values with those of their adopted countries, since their cultural influences pervade through multiple generations.[5] Culture also influences how difficult news is processed and how willingly an individual engages with advance care planning and advance directives.[4,6]

In many home countries of the South Asian diaspora, there is minimal exposure to palliative care services.[5] In many South Asian cultures, maintaining harmony in the clinician–family relationship means avoiding direct confrontation, minimizing distress, and preserving the family unit. This often manifests as a reluctance to openly discuss prognosis or end-of-life care, because such conversations may be perceived as disrespectful or as diminishing hope. Instead, decision making tends to be shared among family members, sometimes overriding individual patient autonomy.[4,5,7] In the West, decision making happens through discussions with the health care team and is built upon patient autonomy.[4] In contrast, South Asian communities avoid discussions about illness and death and commonly take a family-based approach to decision making.[8,9] These taboo conversations may result in family members withholding information from the patient, commonly referred to as “family autonomy” in the literature.[10] Some have argued that family autonomy embodies the holistic meaning of autonomy because of its relational nature. This “relational autonomy” identifies and protects a patient’s best interests within the South Asian community; it acknowledges an individual’s relationships with their family in decision making.[4] Unsurprisingly, the shift toward Western-informed patient-driven care confuses the South Asian diaspora. This confusion stems from the shift in power from the medical team toward the patient and a separation of the individual from the family unit. This is considered a foreign concept since the patient and family are commonly seen as entities within South Asian communities.[5,11]

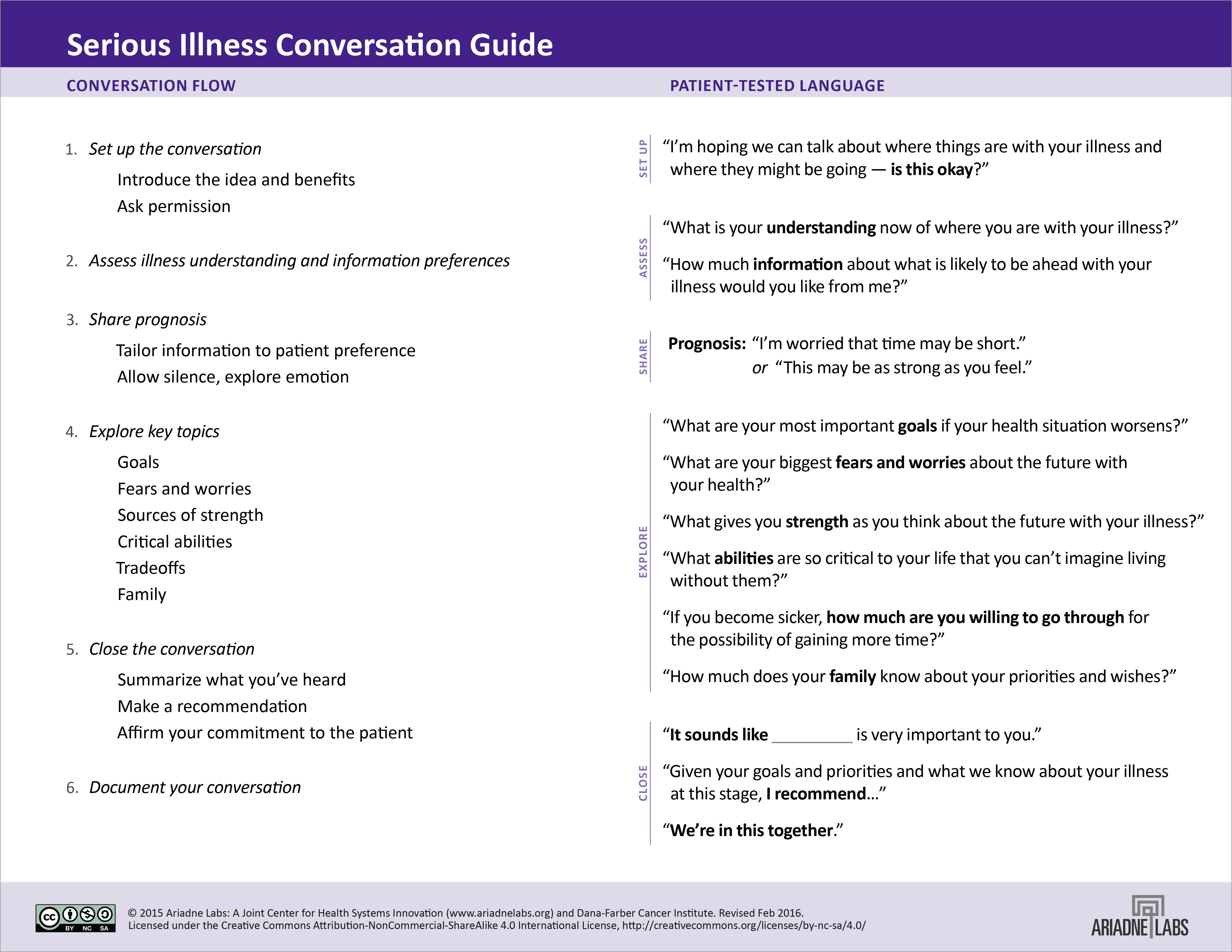

Understanding these cultural nuances is crucial, especially in the context of integrating Western health care practices with those of the South Asian diaspora. Standardized tools, which include the Serious Illness Conversation Guide (SICG), have been developed to facilitate patient-centred discussions when a patient is faced with a serious illness.[6] The SICG is a structured framework developed by Ariadne Labs to support health care providers and patients with serious illnesses in exploring the patient’s values and goals and the delivery of medical information.[6] However, while this tool is used in Western health care settings, its effectiveness among diverse cultural groups, such as the South Asian community, remains underexplored. Given that cultural beliefs influence how illness, prognosis, and decision making are approached, there is a need to evaluate whether the SICG’s language and structure also benefit South Asian patients and their families.

The South Asian community is the largest visible minority group in Canada, particularly in British Columbia; it comprised 28% of the province’s total visible minority population in 2021.[12] With the anticipated increase in demand for palliative care within Canada, it is crucial to provide culturally sensitive and culturally appropriate care to these communities.[13] However, there is limited research on how the SICG is perceived and used within the South Asian community, particularly among English-speaking individuals. We explored how South Asian patients and families understand advance care planning and advance directives in the context of serious illness discussions using the SICG. Our findings will inform strategies for improving advance care planning and advance directives conversations within this community.

Methods

Study design

We recruited English-speaking members of the c community from the Lower Mainland of BC.[8] Participants were 18 years of age or older. Recruitment materials were disseminated through community partners, and subsequent recruitment occurred through chain-sampling recruitment.

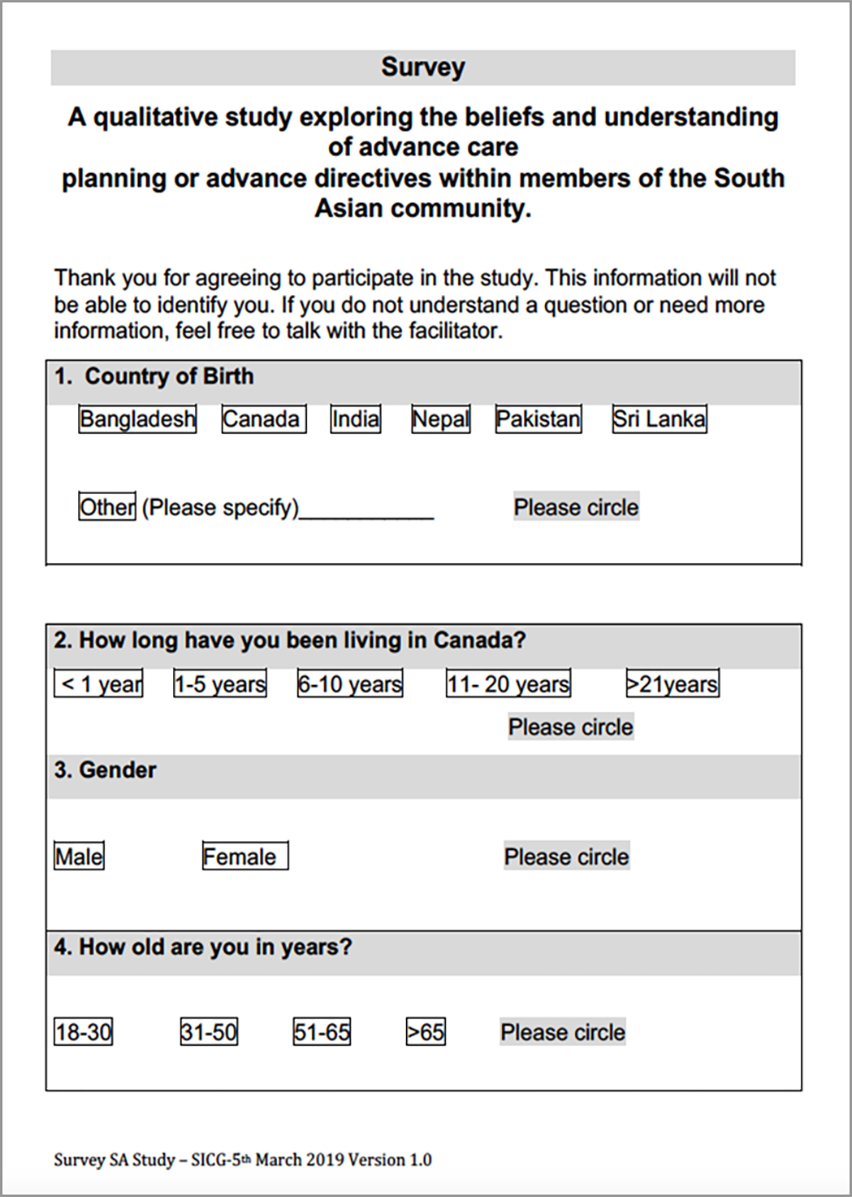

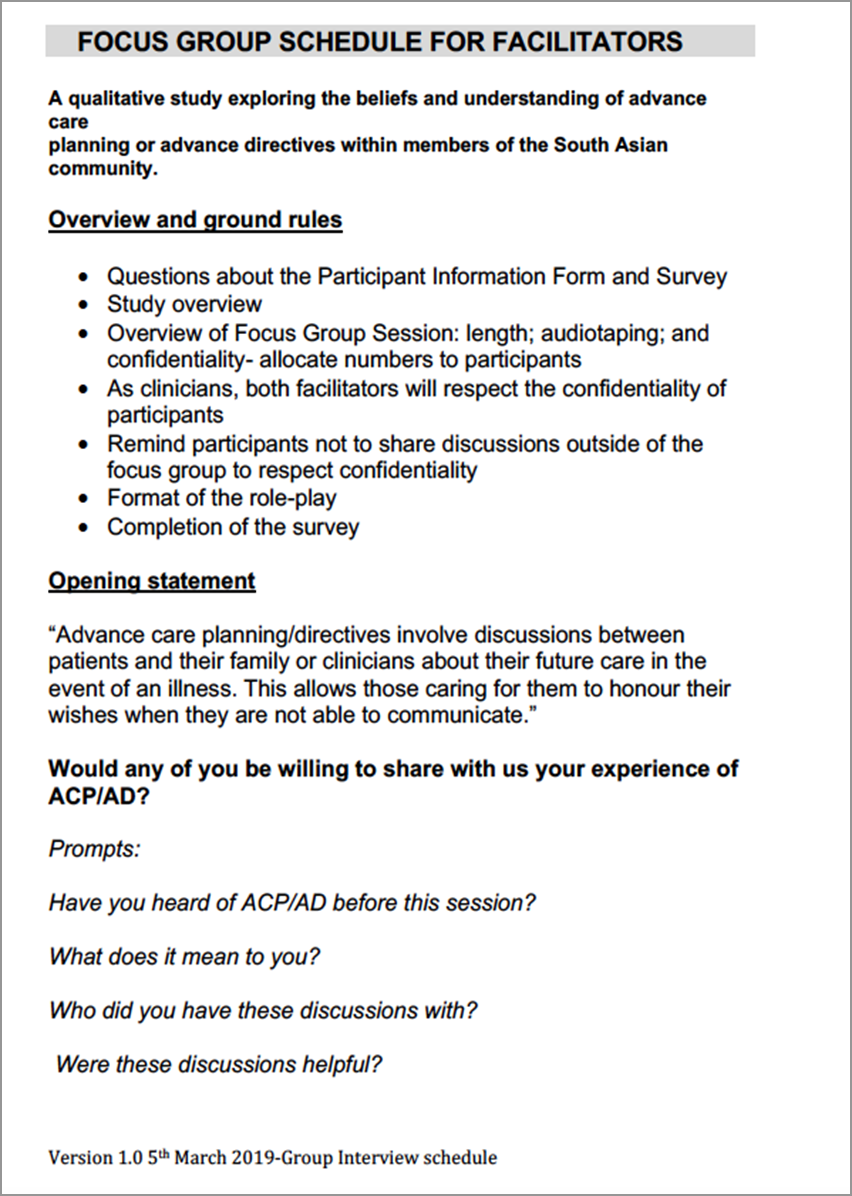

For this qualitative study, we used a survey [Figure S1] and focus groups to explore participants’ understanding of advance care planning and advance directives. The survey included questions about demographics and awareness of advance care planning and advance directives. During the focus groups, participants witnessed a role-play exercise that simulated a conversation between a patient and a physician using the SICG. Facilitators used natural pauses in the SICG to prompt participants to reflect on each question’s meaning, clarity, and cultural appropriateness [Figure S2]. Participants were then encouraged to suggest alternative wording that might better align with South Asian cultural norms. The discussions were facilitated by using semi-structured questions, which allowed direct responses to SICG content and encouraged open-ended dialogue about broader themes of advance care planning and advance directives. Focus group discussions used prompts from the 2016 SICG [Figure S3], the version used by the research team’s health authority at the time of the study.[6]

Data collection and analysis

Qualitative research seeks to understand phenomena through personal experiences.[14] We used interpretive phenomenological analysis to identify themes from interviews and describe how individuals of South Asian heritage approach advance care planning and advance directives discussions using the SICG.[15]

Five focus groups, which were shifted to an online format due to COVID-19 restrictions, were conducted with all researchers present. Sessions were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using NVivo 12 (Lumivero, formerly QSR International Pty Ltd.).[16] Two researchers of South Asian heritage facilitated and demonstrated the SICG. All four researchers, experienced palliative care clinicians, contributed to the process. Data analysis followed an inductive approach, using a reflexive lens to identify concepts and patterns from participants’ perspectives. Field notes and researchers’ shared experiences informed the process. Codes were developed based on consensus after thematic saturation, grouped into categories, and later refined into the study’s key themes.

The University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board approved this study (H19-02322). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study began.

Results

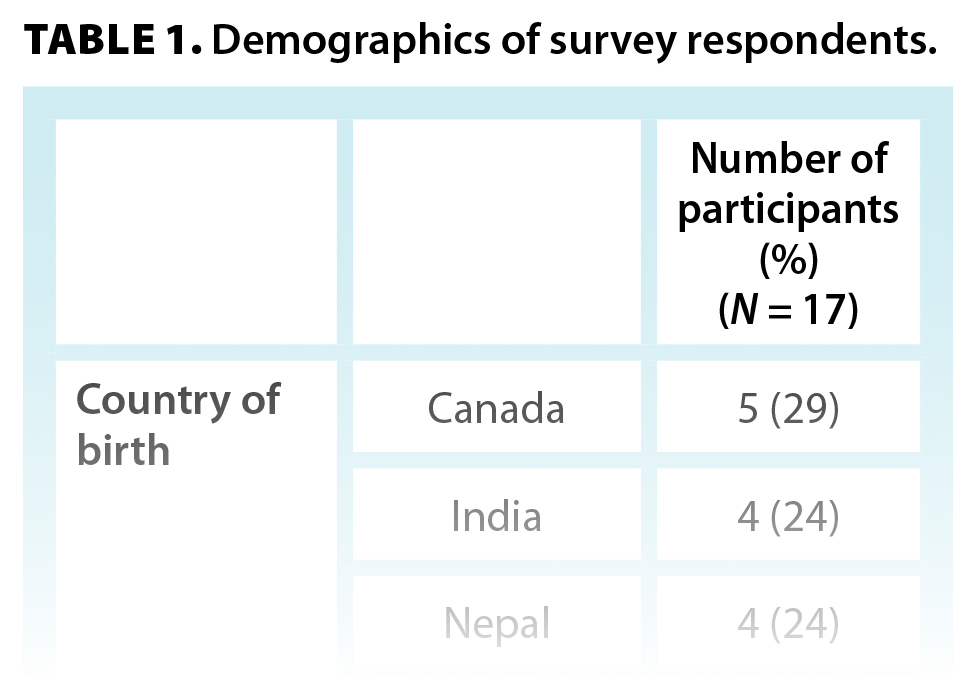

Eighteen individuals participated in the focus groups, but one survey was left blank (N = 17). Most participants were female (76%), were aged 18–50 years (76%), had a university degree (82%), had lived in Canada for at least 10 years (88%), and identified as Hindu (59%) [Table 1]. No gender-specific patterns were observed in the data.

Eighteen individuals participated in the focus groups, but one survey was left blank (N = 17). Most participants were female (76%), were aged 18–50 years (76%), had a university degree (82%), had lived in Canada for at least 10 years (88%), and identified as Hindu (59%) [Table 1]. No gender-specific patterns were observed in the data.

Key themes

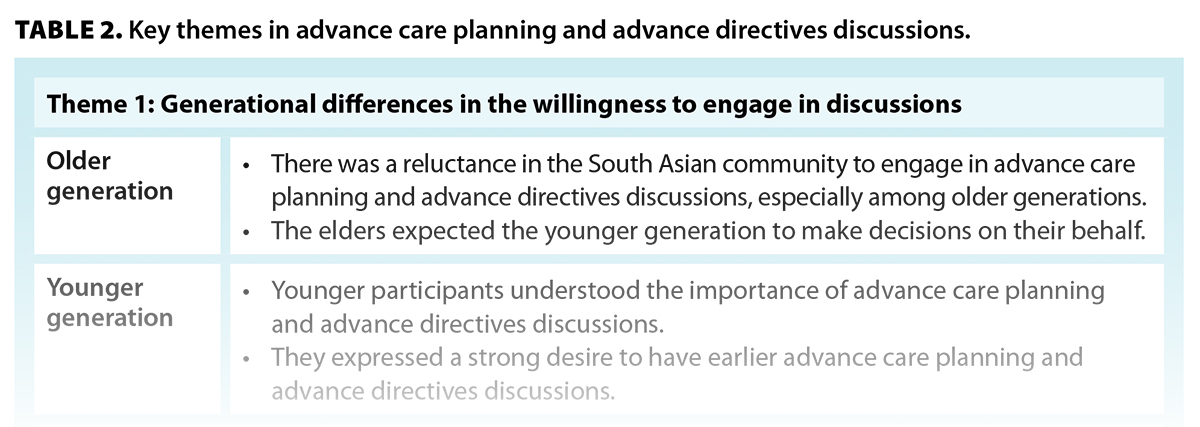

Participants shared the following themes: the generational differences in the willingness to engage in advance care planning and advance directives discussions; the family structure during discussions; and the power differential between patients and health care providers [Table 2]. Quotations that illustrate these themes are attributed using the format (G#-P#), where G# refers to the focus group and P# indicates the participant.

Generational differences in the willingness to engage in discussions. Most participants did not have any direct experience with advance care planning and advance directives discussions. Most of their knowledge stemmed from indirect experiences—for example, previous deaths in the family, family and/or friends dealing with cancer, or family members working in health care. Yet, they knew advance care planning may involve discussions about do-not-resuscitate status and preferences for medical care.

Familiarity with Western health care models affects advance care planning and advance directives discussions. Increased exposure to Western health care perspectives positively correlates with a willingness to engage in these discussions. This was evident with the younger members of our focus groups. They understood the importance of advance care planning and advance directives discussions when making medical decisions, particularly within a Western health care model, and they expressed a desire to have earlier discussions.

Death and dying are taboo subjects in South Asian communities due to the fear that these conversations are disrespectful and remove hope, especially among older generations. One of the participants described this phenomenon as a “cultural veil”:

“[There is a reluctance] to admit weakness or difficulty. . . . Personal situations are harder to admit. . . . There is a cultural veil around deeply personal conversations, making advanced care discussions even more difficult.” (G2-P3)

The symbol of a veil was corroborated by other participants—a phenomenon that prevents these discussions with healthy family members and delays these conversations until an individual is too ill.

“There is a relationship of respect with elders. . . . Bringing up these topics could be seen as disrespectful or wishing harm. . . . Even thinking about it is considered disrespectful.” (G2-P4)

A fatalistic belief was prevalent among our focus group participants, especially in older generations. This belief was described as a predetermined view and is a common reason for delaying or avoiding difficult conversations. “What will be will be” was an accepted rationale for not having these discussions.

“It’s beyond human capacity; we shouldn’t try. . . . Things will be taken care of as they will.” (G2-P3)

“Whatever happens will happen. . . . The Almighty will provide the planning.” (G2-P1)

Most participants acknowledged the difference between health care delivery in Canada versus their home country. When referring to their home country—where an individual was born and raised, or their stated ancestral home—participants said that palliative care services were not well established or available. Advance care planning and advance directives discussions are embedded within but are not exclusive to palliative care services. The paucity of palliative care services in their home countries results in a decreased awareness of advance care planning and advance directives in medical care. Hence, these discussions are less likely to occur.

“In my [home] country . . . advanced care planning doesn’t exist. . . . Decisions are made by family members.” (G2-P3)

Filial piety was a prevalent expectation within the focus groups. Older generations expect, out of duty, that the younger generation will make decisions for them.

“We don’t have to think about what will happen to us. Our kids will think about what they will do for us.” (G3-P1)

“So, when we go off, when we get old and [we’ve] got to make [decisions], our kids will make the decision with the best of their family.” (G3-P5)

Despite a lack of advance care planning and advance directives discussions, elders assume their children will know their wishes. The younger generation expressed concerns about this assumption, because it was described as a major responsibility placed upon them, yet they maintain respect for their elders and understand the reasoning behind this expectation.

“I’d be making decisions for [my parents] based on what I think they would want, but not explicitly knowing what it is.” (G2-P4)

Younger participants are faced with a filial paradox in relation to their duties. Hence, they expressed a desire to have earlier advance care planning and advance directives discussions to alleviate the internal conflict of sole responsibility for decision making.

“Taking that pressure off from everybody else and making sure . . . everyone knows what your decision is. I wouldn’t want my parents to take the burden on.” (G4-P1)

Family structure during discussions. In the South Asian community, family members play a major role in making health care decisions. This is in keeping with the collectivist approach that is prevalent within this community, especially among older generations. This concept of filial piety was evident throughout our focus groups. In the South Asian community, autonomy is not solely about the individual, but also incorporates the interests of the family unit. This family-centred approach is known in the literature as “relational autonomy.”[4,17] Between the generations, the dominance of relational autonomy varies. In our study, the younger generation understood the importance of involving family during decision making but shared their concerns about the dominance of a family-centred approach.

“I think . . . a lot of South Asian families [are] very family oriented, and [the] family [makes] decisions.” (G4-P1)

“Our culture expects you to do everything with your family. They are involved in every kind of decision.” (G5-P1)

In our focus groups, relational autonomy was stated to be more dominant among the older generation. It preserves hope and maintains a facade around difficult conversations. The younger participants acknowledged that love is the primary motivator for this illusion. It is described as compassionate care by protecting members of the community during times of illness.

“That desire to kind of hold on to hope would kind of shut down any conversations of ‘If you become sicker, what would you do?’ That would be very triggering.” (G5-P2)

“In our culture, lots of people say ‘Don’t tell mom, dad, grandpa, grandma what’s going on, because they’ll lose hope.’” (G1-P2)

The family hierarchy within South Asian communities is a powerful force when making decisions regarding health. Due to this hierarchy, the responsibility for making decisions is usually given to the older members of the family. Younger participants exert minimal influence within this hierarchical structure. Furthermore, a large family increases the risk of competing opinions, as this hierarchy becomes more pronounced. These power dynamics contribute to confusion when identifying a substitute decision-maker. This complex family process can obscure the patient’s wishes during the conversation.

“We have a large family; everybody has a different idea of what we should be doing. . . . There is a lot of say from the family. Because the kids are speaking on your behalf, you have your grandkids speaking on your behalf, but nobody really knows what the person would want.” (G1-P3)

Power differential between patients and health care providers. Autonomy is one of the central tenets in the provision of health care in Canada. Older generations and new immigrants from South Asian communities may not fully appreciate this patient-centred approach. In South Asian countries, the health care provider takes a leading role in directing care within the therapeutic relationship. In their home countries, the physician is viewed as the expert, and their authority matters the most in decision making. A physician’s paternalistic approach to care is expected and welcomed.

In our focus groups, there were differing opinions between generations about the extent of power held by the physician. Most participants commented on how older generations view the physician as an authority figure. Hence, the younger members of our focus groups stated that health care providers, especially physicians, have a pivotal role in initiating advance care planning and advance directives discussions. For the elders, this approach can increase their willingness to engage in difficult conversations. Paradoxically, the older generations are hesitant to ask the physician questions due to this power imbalance.

“With the older generations, a physician is a means of authority. . . . They expect everything to come from the physician. There is no real expectation of two-way communication.” (G2-P1)

Younger participants appreciated and expected an opportunity to partner with health care providers in their care. There was no perception of a power imbalance between them and health care providers. They were comfortable with the concept of actively being a part of their health care decisions. They understood the duty of health care teams in fostering patient autonomy and building therapeutic relationships. This understanding among younger participants was highlighted by their comfort in having these conversations independently with their health care provider. The younger generation saw the physician as a partner in making their health care plan.

“[I] might actually want to only have that conversation alone with the doctor.” (G4-P3)

Within South Asian communities, there is an expectation about accompanying older members during their medical appointments. Younger participants raised concerns about language barriers and a need for an interpreter, which would be addressed by the presence of family. More importantly, the family can selectively share information with the patient and maintain the facade of hope. This is in alignment with the phenomenon of the cultural veil.

“A big part of our culture . . . [is] to shelter our older family members [from] having harsh questions presented to [them].” (G5-P2)

Recommendations for the Serious Illness Conversation Guide

A clinician’s goal is to provide patient-centred care, which must include an understanding of the culture of their patients and their families. The intentional language used during advance care planning and advance directives discussions is important, particularly when cultural nuances exist. Words and phrases in a conversational tool must include cultural awareness to achieve its desired outcomes and prevent misinterpretation. A tool that incorporates cultural differences and an understanding of the impact of language is vital in clinical practice.

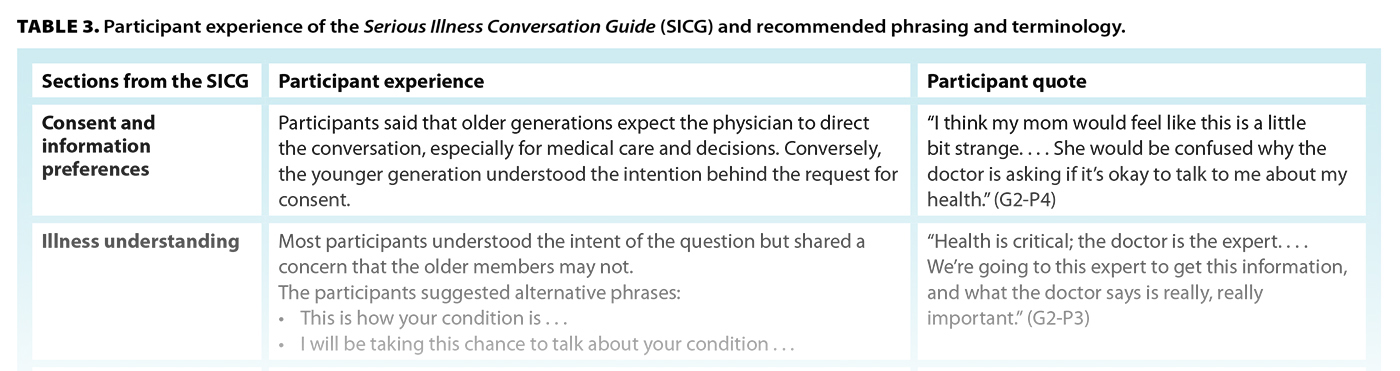

The SICG was used as a foundation for discussions during our focus groups. This tool has natural pauses within its structure. We used these pauses as opportunities for discussion. The participants provided suggestions for phrasing or wording changes in the SICG to facilitate cultural sensitivity within the South Asian community [Table 3].

Discussion

The findings from our focus groups align with the literature on barriers to advance care planning and advance directives discussions in the South Asian community. These barriers include a taboo about death and dying, particularly with elders due to power dynamics; the limited awareness and understanding of palliative care services in South Asian countries; a fatalistic view in medical decision making; a deference to family in medical conversations; and the perception of health care providers, especially physicians, as the primary decision-makers.[20-24] These barriers are more pronounced among older generations.

Racial and ethnic disparities in advance care planning and advance directives discussions are well documented in minority communities.[25-26] As the largest visible minority group in Canada, the South Asian community faces distinct challenges in these conversations. However, health care culture is evolving to improve these conversations. Tools like the SICG have been developed to facilitate advance care planning and advance directives discussions in the general population, but no research has explored its use among English-speaking Canadians of South Asian origin. Our study contributes valuable insights on the experiences of this community with the SICG.

Effective palliative care requires strong communication skills, particularly in understanding patients’ goals and values. Our study builds on the SICG’s foundation by emphasizing cultural nuances when using the tool with English-speaking South Asian Canadians. Participants’ feedback on alternative wording and phrases provided a relativistic perspective on the SICG. Their insights will help clinicians navigate the tension between traditional beliefs from their countries of origin and the realities of health care in Canada and thus enhance the skills needed to have palliative care and serious illness conversations with the South Asian community.

Our study benefited from the diverse cultural backgrounds of our research team, which included South Asian, Chinese, and Filipino researchers. All have experience in collectivist cultures, where decision making is often shared, which strengthened the interpretation of the data from this perspective. The team’s cultural background enhanced the reflexivity of the data analysis and enriched discussions during theme consensus building. While a perspective from a traditional Western lens may have added additional viewpoints, the research team’s extensive experience in a Western health care system ensured both Western and Eastern perspectives were incorporated into the analysis.

All our researchers work primarily in hospice and palliative care settings and are experienced users of the SICG. However, we acknowledge that advance care planning and advance directives discussions extend beyond hospice care, as palliative care services are increasingly integrated earlier in the patient’s journey. The SICG is applicable across the care continuum for all patients with serious illness, and our findings have relevance for specialists across health care sectors, particularly when engaging with the South Asian community.

Study limitations

Our study focused on English-speaking Canadians of South Asian origin from the Lower Mainland of BC. While the findings cannot be generalized to the broader South Asian Canadian community, they provide valuable insights into challenges in providing care to this group. We intentionally selected English-speaking participants to evaluate the SICG as an English-delivered tool, but we acknowledge that due to the South Asian community’s diversity—encompassing a variety of beliefs, languages, and cultural practices—the findings represent only one aspect of the broader experience.

Participants were presented with hypothetical case studies, which do not fully capture the complexity and emotions of real-life scenarios. However, they were encouraged to draw on personal experiences to connect with the case study and share perspectives as family members or patients. Despite the artificial nature of those simulations, meaningful insights were gained from the focus groups.

While most participants identified as Hindu, this does not imply that the findings are representative of a specific religious perspective, because the South Asian community encompasses diverse religious groups. Additionally, most participants lacked direct experience with advance care planning and advance directives discussions, which limits the generalizability of the findings. However, the results provide valuable insights into the cultural influences that shape advance care planning and advance directives discussions within South Asian communities.

Further research should aim to include a broader demographic representation, including older age groups, male participants, varied socioeconomic backgrounds, newly arrived immigrants, individuals from different religious communities, and those with personal experience in advance care planning and advance directives discussions.

Conclusions

In keeping with the collectivistic nature of the South Asian community, our study highlights the predominant role family plays during advance care planning and advance directives discussions and medical decision making. It also highlights the potential barriers to and the benefits and challenges of using a Western-devised tool for having serious illness conversations with members of the South Asian community in Canada. The SICG’s choice of words and phrases were viewed as predominantly individualistic. Our findings help facilitate cultural awareness and sensitivity in clinical practice among members of the South Asian community. Hence, clinicians can appreciate the impact of the culture and family during advance care planning and advance directives discussions.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Lennie Tan and Ms Amy Booth for their support in recruitment and Ms Shannon Long for her literature review.

Supplementary figures

|

|

| FIGURE S1. The survey used for this qualitative study. | FIGURE S2. The focus group schedule for facilitators. |

|

| FIGURE S3. Excerpt from the Serious Illness Conversation Guide. |

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994-2003. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271.

2. Dias LM, Frutig M de A, Bezerra MR, et al. Advance care planning and goals of care discussion: Barriers from the perspective of medical residents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:3239. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043239.

3. Kang L, Liu X-H, Zhang J, et al. Attitudes toward advance directives among patients and their family members in China. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:808.e7-808.e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.05.014.

4. Bharadwaj AD. Culture in end-of-life care. Perspect Biol Med 2021;64:271-280. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2021.0012.

5. Khosla N, Washington KT, Shaunfield S, Aslakson R. Communication challenges and strategies of U.S. health professionals caring for seriously ill South Asian patients and their families. J Palliat Med 2017;20:611-617. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0167.

6. Ariadne Labs. Serious illness conversation guide. 2016. Accessed 3 April 2025. www.ariadnelabs.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/SI-CG-2017-04-21_FINAL.pdf.

7. Martina D, Lin CP, Kristanti MS, et al. Advance care planning in Asia: A systematic narrative review of healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitude, and experience. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22:349.e1-349.e28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.12.018.

8. Con A. Cross-cultural considerations in promoting advance care planning in Canada. Health Canada, BC Cancer Agency, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, 2008. Accessed 3 April 2025. www.virtualhospice.ca/Assets/Cross%20Cultural%20Considerations%20in%20Advance%20Care%20Planning%20in%20Canada_20141107113807.pdf.

9. Lim S, Mortensen A, Lee H. Advance care planning: Guidelines for working with Asian patients and their families. Auckland, New Zealand: WDHB Asian Health Support Services, 2012. Accessed 3 April 2025. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/62e8790dafcbaf632ac96c76/t/674e56f0342b894b97946ac9/1733187314770/Asian+health+support+services+guidelines+for+advance+care+planning.pdf.

10. Khan RI. Palliative care in Pakistan. Indian J Med Ethics 2017;2:37-42. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2017.007.

11. King-Shier K, Lau A, Fung S, et al. Ethnocultural influences in how people prefer to obtain and receive health information. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:e1519-e1528. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14281.

12. Statistics Canada. Census profile, 2021 census of population: Profile table. Last modified 2 August 2024. Accessed 10 March 2025. www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm.

13. Woods RR, Coppes MJ, Coldman AJ. Cancer incidence in British Columbia expected to grow by 57% from 2012 to 2030. BCMJ 2015;57:190-196.

14. Castleberry A, Nolen A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr Pharm Teach Learn 2018;10:807-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2018.03.019.

15. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

16. Lumivero (formerly QSR International Pty Ltd.). NVivo 12 [software]. 2017. www.qsrinternational.com.

17. Gómez-Vírseda C, de Maeseneer Y, Gastmans C. Relational autonomy: What does it mean and how is it used in end-of-life care? A systematic review of argument-based ethics literature. BMC Med Ethics 2019;20:76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0417-3.

18. Biondo PD, Kalia R, Khan R-A, et al. Understanding advance care planning within the South Asian community. Health Expect 2017;20:911-919. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12531.

19. Doorenbos AZ, Nies MA. The use of advance directives in a population of Asian Indian Hindus. J Transcult Nurs 2003;14:17-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659602238346.

20. Kwak J, Ko E, Kramer BJ. Facilitating advance care planning with ethnically diverse groups of frail, low-income elders in the USA: Perspectives of care managers on challenges and recommendations. Health Soc Care Community 2014;22:169-177. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12073.

21. Periyakoil VS, Neri E, Kraemer H. Patient-reported barriers to high-quality, end-of-life care: A multiethnic, multilingual, mixed-methods study. J Palliat Med 2016;19:373-379. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2015.0403.

22. Rao AS, Desphande OM, Jamoona C, Reid MC. Elderly Indo-Caribbean Hindus and end-of-life care: A community-based exploratory study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1129-1133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01723.x.

23. Sharma RK, Khosla N, Tulsky JA, Carrese JA. Traditional expectations versus US realities: First- and second-generation Asian Indian perspectives on end-of-life care. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:311-317. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1890-7.

24. Worth A, Irshad T, Bhopal R, et al. Vulnerability and access to care for South Asian Sikh and Muslim patients with life limiting illness in Scotland: Prospective longitudinal qualitative study. BMJ 2009;338:b183. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b183.

25. Radhakrishnan K, Van Scoy LJ, Jillapalli R, et al. Community-based game intervention to improve South Asian Indian Americans’ engagement with advanced care planning. Ethn Health 2019;24:705-723. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1357068.

26. Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Bonares MJ, et al. Association be-tween Chinese or South Asian ethnicity and end-of-life care in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ 2020;192:E266-E274. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190655.

Dr Joshi is a palliative physician in the Richmond Integrated Hospice Palliative Care Program, Vancouver Coastal Health. Ms Musa is a palliative clinical nurse educator in the Richmond Integrated Hospice Palliative Care Program, Vancouver Coastal Health. Dr Kara is a palliative physician in the Fraser Health Hospice Palliative Care Program. Ms Wang is a registered nurse in Vancouver Coastal Health. Dr Ruiz is a program advisor (data and measurement) with Vancouver Coastal Health, Medical Quality, Leadership and Practice. Mr Liow is a research facilitator in the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (Coastal and Richmond branches). Ms Sheikh is a research coordinator in the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute (Richmond branch).

Corresponding author: Dr Amrish Joshi, Amrish.Joshi@vch.ca.