Papapalooza: A low-barrier community-based cervical cancer screening initiative

ABSTRACT: Addressing barriers to cervical cancer screening as a public health priority in British Columbia requires innovative approaches. Community-based health promotion initiatives like Papapalooza connect the public with low-barrier cervical cancer screening and accessible health education, offering inclusive, celebratory, and trauma-informed Pap test experiences through pop-up events.

To determine whether patients support Papapalooza as a strategy to reduce screening barriers, we administered 354 pre-Pap surveys and 309 post-Pap surveys to 533 Papapalooza attendees at five events held between March and June 2023. Identified barriers included inaccessible primary care, provider-related factors, and personal factors. Surveys showed increased knowledge and comfort accessing and understanding the importance of screening, with 93.8% of post-Pap survey participants “very likely” to attend another Papapalooza.

Community-based health promotion is an acceptable means of connecting patients with important screening, while creating meaningful opportunities to enhance health literacy.

A study to determine whether a community-based pop-up event model is an acceptable strategy among patients to improve access to cervical cancer screening.

Cervical cancer deaths are preventable, thanks to advances in the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine and population-based cervix screening programs. However, approximately 1300 people in Canada are diagnosed with cervical cancer yearly, with roughly 400 of these diagnoses leading to death.[1] While routine cervical cytology screening is recommended every 3 years, or HPV screening every 5 years, for people with a cervix who are aged 25 to 69, 37% of those diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer in Canada between 2011 and 2013 were not up to date on screening.[2]

British Columbia operates a publicly funded cervical cancer screening program. Previously, this included Papanicolaou (Pap) cytology testing, though recent advancements to the screening program, liquid-based cytology, and HPV self-screening aim to increase capacity for testing and mitigate access barriers. Despite these advancements, inequities and access barriers persist. Notably, individuals from equity-deserving populations (e.g., 2SLGBTQIA+, those of low socioeconomic status, those who live in rural communities) continue to experience barriers to culturally safe and trauma-informed screening.[3] The COVID-19 pandemic and primary care crisis have further exacerbated these inequities, leading to lower screening rates and increased mortality.[4,5]

Community-based cancer screening events such as cultural gatherings, charity runs, and health fairs can circumvent these barriers.[6] They aim to attract large numbers of people, increase health literacy, and provide culturally and linguistically accessible health care.[6,7] Studies suggest that community-based cancer screening events positively influence attendees’ decisions to participate in screening.[6]

Background

Papapalooza is a community-based pop-up cervical cancer screening initiative that aims to improve access for underserved BC populations. A secondary intention is to enhance health literacy related to preventive care. Events embody a Pap party, with colorful decorations, snacks, and music. Five Papapalooza events were held across BC in 2023. Patients had 10- to 15-minute appointments to complete the exam and receive education from physicians. At least one physician at each event had training in trauma-informed care. Patients were provided with brochures outlining the BC Cancer guidelines and were referred to the BC Cancer website for further information. All attendees were informed of their results, and positive tests were followed by respective Papapalooza host clinics.

This study’s purpose was to determine whether the Papapalooza community-based pop-up event model is an acceptable strategy among patients to improve access to screening.

Methods

Ethics approval for this study was obtained through the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (H22-03798). Pre-Pap and post-Pap web-based Qualtrics surveys were administered at five Papapalooza events held between March and June 2023 in Nanaimo, Victoria, Vancouver, Kelowna, and Prince George. Questions addressed barriers to accessing Pap tests, knowledge of cervical cancer screening, and perspectives on the event. Surveys included multiple-choice, short-answer, and Likert-scale questions.

Events were promoted on social media [Figure 1], in newspapers, and on the radio. People were eligible to attend Papapalooza if they were 25 to 69 years of age, due for a Pap test, and unable to access screening through alternative means. All Papapalooza attendees were invited to complete the surveys. Participants completed an informed consent form and self-administered the surveys. All responses were anonymous. No remuneration was offered for participation.

Inductive qualitative analysis of short-answer responses was performed by three study team members. All three reviewers independently coded a randomly selected sample of 10% of responses. The research team, including two members who did not participate in data analysis, reviewed the preliminary analysis, generating a list of codes based on commonly identified themes. Analysis of the remaining data set was performed independently by three reviewers, and final codes were assigned based on agreement by at least two out of three reviewers. Quantitative analysis of multiple-choice and Likert-scale questions was performed using Microsoft Excel.

Results

All 533 Papapalooza attendees were eligible to participate in the event. Of those, 354 patients (66.4%) participated in the pre-Pap survey, and 309 patients (58.0%) participated in the post-Pap survey. Of the 354 pre-Pap survey participants, 45 attended the event in Nanaimo, 40 in Kelowna, 61 in Prince George, 90 in Victoria, and 118 in Vancouver.

The majority of pre-Pap survey participants (74.6%) had received at least one Pap test previously. Of those, 17.7% had their previous Pap test within the recommended screening interval. Of the 354 pre-Pap survey participants, 64.1% responded that a health care provider had discussed the importance of cervical cancer screening with them. When asked why their screening was not up to date, most pre-Pap survey participants (65.1%) reported that they did not have a primary care provider. However, even participants with a provider reported challenges: “Very difficult to book appt. Only does [Paps] on certain day of the month.” “My [doctor] is out of his office frequently and there are very long wait lists to see him.” The COVID-19 pandemic was also frequently mentioned: “Covid made walk-in clinics a nightmare.”

Many pre-Pap survey participants reported feeling uncomfortable with their primary care provider performing Pap tests: “Male family doctor and I prefer a female practitioner for a [Pap].” “Don’t know him well enough to have a [Pap] done by him.” “I was a sex worker for 10 years and [am] pretty shy about finding the right doctor to talk to about it.”

Unique barriers were shared by certain populations, such as those who were new to BC, lived in remote communities, or had a history of medical trauma: “I’m waiting for my Permanent Residence, so I don’t have a family doctor and I can’t leave the country.” “[GP is] more than 1 hour away.” Another participant shared their history of “violation of position of power by doc in office.”

Personal factors like “never getting around to it” and lack of child care were reported barriers. Of the pre-Pap survey participants, 12% reported not knowing when their next Pap test should be: “Had a couple abnormal [Paps] but was not followed up with.” “I was not reminded I was due.” Other participants shared misunderstandings of cervical cancer screening recommendations: “I have [only] one partner.” “My family doesn’t have cancer in the family.”

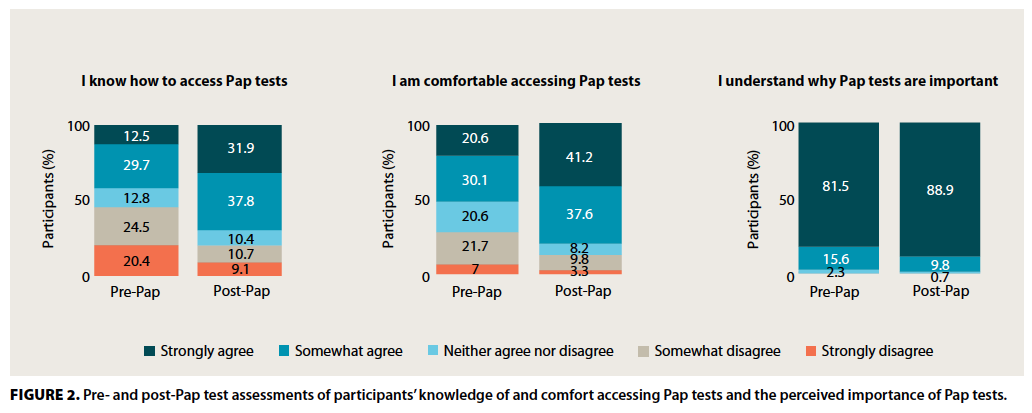

Before the event, only 12.5% of pre-Pap survey participants strongly agreed that they knew how to access Pap tests, and only 20.6% strongly agreed that they felt comfortable accessing Pap tests, despite 81.5% strongly agreeing that screening was important [Figure 2]. After attending Papapalooza, post-Pap survey participants demonstrated a global increase in knowledge, comfort, and perceived importance of screening [Figure 2].

In the post-Pap survey, participants described the event as empowering and inclusive, with an uplifting environment: “Positive space, women supporting women.” “I liked the . . . celebration.” Participants also appreciated the educational nature of the event: “Informative [. . .] before, during, and after.”

Participants commented on their positive experiences with Papapalooza providers: “The doctor was very kind, understanding and informative.” “Approachable and made me comfortable.” “Explained all the steps that were going to happen.” “Gained my consent multiple times throughout the exam.”

Participants described the event as accessible, noting convenience, efficiency, and availability of appointments: “Appreciated that it was fast and efficient, and the appointment happened on time, allowing my schedule for the day to stay on track.”

Overall, 93.8% of post-Pap survey participants indicated they were very likely to attend another Papapalooza or community-based health care event.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that community-based health promotion events like Papapalooza are an acceptable strategy among patients to improve accessibility and increase knowledge of and participation in cervical cancer screening. An overarching theme explaining why patients attended Papapalooza was a lack of accessible primary care. Innovative community-based events like Papapalooza can reconnect patients with low-barrier screening, given the ongoing BC primary care crisis.

Many pre-Pap survey participants described avoiding screening due to discomfort with their primary care provider, demonstrating the importance of provider–patient rapport. Some appreciated that their Papapalooza provider was female, with several reporting that lack of access to a female provider was a barrier. While the literature on Pap provider gender preferences is inconclusive, our results demonstrate that providers’ gender identity factors into some patients’ decision to access screening.[8,9]

Many patients, particularly those from equity-deserving groups, have experienced sexual and medicalized trauma, leading to heightened anxiety and shame around gynecologic procedures and reduced engagement with cervical cancer screening.[10,11] Post-Pap survey participants indicated that a comfortable and inclusive environment encouraged participation from patients who might otherwise feel excluded from this care. Anyone interested in hosting similar events should aim to preserve this environment by practising trauma-informed care, ensuring consent and clear communication throughout the exam, and prioritizing patients’ dignity.

Several pre-Pap survey participants’ responses reflected their misunderstandings regarding cervical cancer screening and a desire for greater health education. The literature suggests that cervical cancer screening rates more than double after educational interventions.[12] We aimed to provide low-barrier education through social media, a take-home brochure, and discussions with physicians. Our results emphasize patients’ desire for and the importance of this education as an intrinsic part of routine preventive care.

We acknowledge that the primary means of recruitment for our study was through social media, which may skew results toward younger demographics. Additionally, event attendees dissatisfied with their experience may have opted out of the survey, leading to response bias. Additionally, our events occurred before the introduction of HPV self-swabs, which now mitigate many of the access and provider-related barriers. Nonetheless, provider-collected HPV swabs and Pap tests remain essential for many patients, including people with a history of atypical screening results or positive self-swabs, those with disabilities or no fixed address, and anyone who would benefit from an in-person exam.

This study demonstrates that Papapalooza is an acceptable community-based cervical cancer screening event. Further engagement with providers and communities will help define how similar events can best serve the needs of our population.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Christine Layton and Kristi Kyle, Papapalooza founders, and Dr Sophie Harasymchuk. They are grateful to the more than 40 medical student volunteers and clinicians across the province whose support was essential to this initiative.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Zhu P, Tatar O, Haward B, et al. Assessing Canadian women’s preferences for cervical cancer screening: A brief report. Front Public Health 2022;10:962039. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.962039.

2. Saraiya M, Steben M, Watson M, Markowitz L. Evolution of cervical cancer screening and prevention in United States and Canada: Implications for public health practitioners and clinicians. Prev Med 2013;57:426-433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.01.020.

3. Racey CS, Albert A, Donken R, et al. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia rates in British Columbia women: A population-level data linkage evaluation of the school-based HPV immunization program. J Infect Dis 2020;221:81-90. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz422.

4. Baaske A, Brotto LA, Galea LAM, et al. Barriers to accessing contraception and cervical and breast cancer screening during COVID-19: A prospective cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2022;44:1076-1083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2022.05.011.

5. Rush KL, Burton L, Seaton CL, et al. A cross-sectional study of the preventive health care activities of western Canadian rural-living patients unattached to primary care providers. Prev Med Rep 2022;29:101913. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101913.

6. Escoffery C, Liang S, Rodgers K, et al. Process evaluation of health fairs promoting cancer screenings. BMC Cancer 2017;17:865. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-017-3867-3.

7. Escoffery C, Rodgers KC, Kegler MC, et al. A systematic review of special events to promote breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening in the United States. BMC Public Health 2014;14:274. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-274.

8. Janssen SM, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Physician’s gender, communication style, patient preferences and patient satisfaction in gynecology and obstetrics: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89:221-226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.06.034.

9. Hoke TP, Berger AA, Pan CC, et al. Assessing patients’ preferences for gender, age, and experience of their urogynecologic provider. Int Urogynecol J 2020;31:1203-1208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04189-0.

10. Marshall DC, Carney LM, Hsieh K, et al. Effects of trauma history on cancer-related screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Lancet Oncol 2023;24(11):e426-e437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(23)00438-2.

11. Mkuu RS, Staras SA, Szurek SM, et al. Clinicians’ perceptions of barriers to cervical cancer screening for women living with behavioral health conditions: A focus group study. BMC Cancer 2022;22:252. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-022-09350-5.

12. Musa J, Achenbach CJ, O’Dwyer LC, et al. Effect of cervical cancer education and provider recommendation for screening on screening rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0183924. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183924.

Ms Dissanayake,* Ms Jiang,* and Ms Wasylyk* are fourth-year medical students at the University of British Columbia. Dr Brown is a resident in the Department of Medicine at UBC. Dr Hussey is a resident in the Department of Emergency Medicine at UBC.

[*co–first authors]