Innovative use of point-of-care ultrasound improves health care on Haida Gwaii

ABSTRACT: Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can improve patient care by reducing diagnosis, treatment, and transport times; reducing transfers; and providing medical care closer to home. However, barriers to acquiring and maintaining proficiency with POCUS result in widespread underuse of this technology. The medical community on Haida Gwaii, a remote archipelago off the coast of British Columbia, is using POCUS in innovative and sustainable ways. Employing an interpretive description methodology and the theoretical framework of the Eco-Normalization Model, we conducted semi-structured interviews with a community physician, a local hospital administrator, and a patient to discover the factors that led to the successful implementation of POCUS. Drivers included local physician “POCUS champions” and the desire to provide better and more compassionate medical care. Enablers included specific medical education, excellent administrative support, a culture of learning and collaboration, and patient satisfaction.

Physician champions of point-of-care ultrasound, along with educational and administrative supports, have significantly enhanced the provision of cost-effective, compassionate, patient-centred care on Haida Gwaii.

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) can improve patient care by expediting the diagnosis and treatment of traumatic and other medical conditions. From its origins in the emergency department, its use has now spread to critical care, hospital, and clinic settings. This important tool is especially valuable in rural health care settings, which often lack immediate access to consultative diagnostic imaging and definitive specialist care.[1,2] Additionally, the use of POCUS can reduce the volume of transfers to referral centres and ease the challenges of patient transport,[2-4] which is the largest barrier in practice for rural emergency department practitioners.[5] Furthermore, patients’ satisfaction with care improves due to immediate access to information on their clinical condition.[4,6] A recent survey on POCUS use among rural health care providers in British Columbia revealed that 43% of those surveyed used it more than once per day.[7]

In 2015, recognizing the barriers to acquiring and maintaining proficiency in POCUS, the University of British Columbia’s Rural Continuing Professional Development program, with the support of the Rural Coordination Centre of BC (RCCbc), launched the Hands-On Ultrasound Education (HOUSE) program, an innovative traveling education program on POCUS designed to meet the unique needs of rural physicians in BC.[8] The program was developed with an understanding and appreciation of potato ethics, a “particular rural health care sensibility” described as “an ethics rooted in the duty to make oneself useful … cooperating in the service of whatever is necessary and actively learning whatever is needed to do so.”[9]

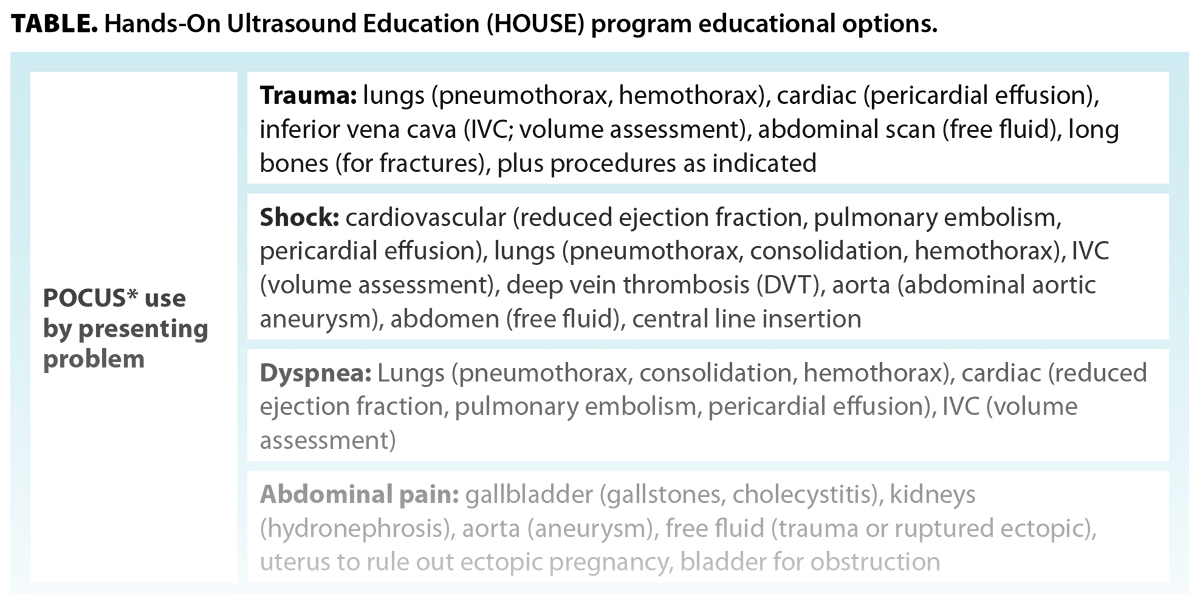

The HOUSE program teaches a wide variety of POCUS applications, and communities customize their learning by creating an agenda from a menu of options [Table]. This can include thematically based learning, such as the multisystem workup of trauma, shock, or dyspnea; specialty-based agendas, such as obstetrics or pediatrics; and agendas based on applications that are not clinically linked, such as exams relevant to the clinic setting (e.g., IUD placement, screening for the presence of an asymptomatic abdominal aortic aneurysm). The course length is determined by the community and can be between half a day and 2 days. Residents and allied health practitioners can be included, at the discretion of the community.

The HOUSE program was piloted on Haida Gwaii in 2015 and was offered again in 2022. HOUSE course instructors, which include experienced rural physicians, have a unique window into rural POCUS patterns of practice across the province. Instructors noted a significant advancement of POCUS skills in the years between the two courses. They were particularly impressed by the depth and breadth of those skills among local practitioners and by the innovative use of POCUS to address challenges in access to health care. We aimed to discover the factors that led to this, in the hopes that this information might be of value to both the HOUSE program and medical communities interested in expanding local POCUS skills.

Haida Gwaii’s population of approximately 5000 (50% Haida and 50% non-Haida) is served locally by two hospitals: Xaayda Gwaay Ngaaysdll Naay (Haida Gwaii Hospital and Health Centre) in Daajing Giids (formerly Queen Charlotte City) and Northern Haida Gwaii Hospital and Health Centre in Gaw (formerly Masset). Xaayda Gwaay Ngaaysdll serves 3000 residents and provides inpatient, clinic, emergency, obstetric, and oncology services. At the time of this research, six family physicians and two midwives were working there. All providers were using POCUS, and two of the physicians, self-described “POCUS champions,” were supporting their colleagues as well.

Haida Gwaii is a remote group of islands off the coast of BC, approximately 200 km by water from the nearest referral centre, in Prince Rupert. Because there is no access to radiology department ultrasound service on Haida Gwaii, patients face expensive and inconvenient travel for this service. Additionally, the difficulties of being without family support during times of illness and uncertainty cannot be understated. Thus, innovations that provide more services locally are of significant value for Haida Gwaii residents.

“We have no [radiology department] ultrasound services on Haida Gwaii, so for a mother to get an ultrasound for her baby, it’s a 7-hour ferry ride. You have to get in a lineup for the ferry 2 hours before it sails. It takes about 45 minutes to unload the ferry. So it’s like 10 hours one way to get to Prince Rupert. And then … you’re there anywhere from 2 to 4 nights in a hotel. And if you have your vehicle … it’s $700 now, and then there’s hotels and then your meals.” (Physician)

Methods

![FIGURE. Eco-Normalization Model and the six critical questions. Adapted from Hamza and Regehr.[10] (POCUS = point-of-care ultrasound).](https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No6_point-of-care-ultrasound_Figure.jpg) We conducted a retrospective evaluation of the factors that led to the emergence of the innovative use of POCUS on Haida Gwaii. Traditional models of program evaluation were not a good fit, because they were generally prospective and focused on programs that were intentional rather than emergent. The Eco-Normalization Model, a theoretical framework derived from implementation science theories, examines the longevity of an innovation within the context of the local ecosystem and explores features of the ecosystem that may enhance (or detract from) the innovation’s longevity.[10] The model gives rise to six critical questions to consider [Figure]. We contextualized the original model to account for this unique application and expanded the original domain of “people doing the work” to “people involved in the innovation” to include the patient perspective.

We conducted a retrospective evaluation of the factors that led to the emergence of the innovative use of POCUS on Haida Gwaii. Traditional models of program evaluation were not a good fit, because they were generally prospective and focused on programs that were intentional rather than emergent. The Eco-Normalization Model, a theoretical framework derived from implementation science theories, examines the longevity of an innovation within the context of the local ecosystem and explores features of the ecosystem that may enhance (or detract from) the innovation’s longevity.[10] The model gives rise to six critical questions to consider [Figure]. We contextualized the original model to account for this unique application and expanded the original domain of “people doing the work” to “people involved in the innovation” to include the patient perspective.

We employed an interpretive description methodology—a methodology well suited to medical education. This is a highly adaptable qualitative approach that “captures the subjective experience of individuals while drawing on lessons from broader patterns within the phenomenon being studied,”[11] which aligned well with the intentions of our study.

The questions arising from the Eco-Normalization framework guided the creation of an interview process. Semi-structured one-on-one interviews approximately 1 hour in duration were conducted by a research assistant via videoconference. Using purposeful sampling, a family physician, a senior hospital administrator, and a local resident who had received POCUS as part of their medical care were interviewed. Transcribed interviews were shared with the research team. Each team member reviewed the interview data independently, recorded reflections, and noted recurring themes. The team convened after each interview to discuss individual reflections, which expanded our collective understanding of the data. Team members included two rural physicians with extensive experience in POCUS education, a HOUSE course program manager with UBC Continuing Professional Development (CPD), a research assistant with UBC CPD, a research scientist with RCCbc, and a rural research facilitator with RCCbc. The diverse perspectives and backgrounds of the research team contributed to the depth of the data analysis. As the findings of the group were collated, the team combined the data into key thematic categories, based on consensus among team members. Ethical approval for our study was obtained from the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board.

Results

Innovative use of POCUS

POCUS is embedded throughout the health care system on Haida Gwaii: there are ultrasound units in the emergency department, on the inpatient ward, in the outpatient clinic, and in outreach clinics to smaller communities. All POCUS users have support for ongoing learning, in that some physicians, “POCUS champions,” make themselves readily available to support colleagues. Three more experienced users regularly record and upload their POCUS images to the electronic medical records system, which makes them available to other members of the health care team (e.g., nurses, physiotherapists, distance-based specialists). Surgeons use the images to assist with pre-op planning, and other specialists (e.g., cardiologists, radiologists, obstetricians) use the images to guide the creation of patient care plans. Local physicians also use POCUS to support local midwives. To our knowledge, no other community in the province is archiving and sharing POCUS images to this degree.

“It’s probably used 10 to 12 times a day, at least, in the clinic.” (Physician)

“When I did have to go for the surgery, the surgeon met me, and he was, like, up to snuff, and he actually had little pictures from the ultrasound.” (Patient)

“Both of [the midwives] are using it. We used to be called in to do the dating and they would watch. And then it became ‘All right; here’s how you do it,’ and [now they] do the dating and we watch.” (Physician)

Drivers of innovation

POCUS champions: A POCUS champion is an informal designation for a highly motivated local physician who has or is acquiring proficiency in POCUS; recognizes the value of it; and supports its integration into the health care system in a variety of ways, such as by providing educational opportunities, access to machines, and one-on-one collegial support. This role is generally not formally recognized or supported outside of crossover from other leadership roles, such as an educational or departmental lead position. For example, the physician we interviewed invested considerable time to work out the process for archiving POCUS images, which involves saving them to and downloading them from the POCUS unit and then manually uploading them into the electronic medical records system. Additional work included supporting the process of acquiring POCUS units, which involved a team-based decision-making process, community fundraising, and administrative support at both the local and health authority levels. This physician was quick to describe their role as building on the work done by the previous champion, a retired physician. Due to the depth and breadth of support provided by this champion, it is unlikely that significant and sustainable POCUS innovation could have developed without this strong driver.

“There are probably two champions, me and [X]. I mean champions in the sense [that] we use [POCUS] all the time. When we’re teaching, we’re promoting it to our colleagues, and we’re also available for consult as well. So, very frequently, we’re asked to review a scan or do a scan as a second opinion, probably several times a week … sometimes in the middle of the night, especially if it’s a really important scan … especially if it’s going to save a transfer for a procedure.” (Physician)

“That’s an additional huge learning curve … to get the information off the device and into the record.” (Physician)

Compassionate care: The understanding that POCUS might allow patients to stay home and avoid a difficult transfer for further investigations was an essential driver of the innovation. When a patient was able to stay home as a result of the use of POCUS, their medical experience was more compassionate and more patient centred. Both providers and patients valued this.

“Is the baby going to survive? That’s a key [indication for POCUS]. … Ensuring that there was a heartbeat and that things were looking healthy [was] very much a game changer, because every one of those women would be so nervous. We’d put them on a ferry, and they’d have a miscarriage on the ferry, or in Prince Rupert, away from their family. Very tragic, tragic stuff … and then they’d have to come back bleeding and cramping on the ferry—like, brutal. And I could tell you, like in 5 minutes, [that the baby was alive].” (Physician)

“My granddaughter … had an ultrasound at the hospital here as an outpatient, and again it was invaluable. … [It] saves a lot of stress, you know, wondering what’s happening or how serious something is. If it’s not something real serious, that really helps bring the stress level down on everybody.” (Patient)

“I realized … that [POCUS] was going to improve patient care more than any other kind of learning I could do, like, hands down, be more effective, be more time efficient, be more satisfied myself. But most importantly, people are going to get better care in community by me doing this and being as good as possible.” (Physician)

“To come and go from here during the winter months is not so easy, because we have the ferry three times a week. So, certainly, [POCUS] saves a lot of worry, and it also saves a big trip. The average person has a tough time financially to do all of that.” (Patient)

Apart from logistic and financial considerations, the physician interviewed emphasized the cultural impact of providing services in community, especially those related to birth and death.

“It is also important for cultural reasons, especially for services around birth and end of life. It is more important for Haida people culturally to want to be born here and to die here.” (Physician)

“As far as dying goes, how does ultrasound help in that experience? There are lots of conditions … an Elder will come in with that are life threatening, that we can kind of give them a sense of how … likely they are to die if they go out. And that’s a key factor in their decision making [to be transferred or not] … because being sent away … you’re alone, you don’t know what’s going on. And then to die there…” (Physician)

Enablers of innovation

Educational considerations: POCUS education that is learner focused, that inspires curiosity over fear, and that is taught locally to the community of physicians was reported as a driving factor in the adoption of POCUS and in ongoing skill acquisition. The HOUSE course, which is taught in rural communities by a mix of rural physician peers and sonographers with an emphasis on a learner-centred, relaxed, and collegial learning environment, was highly valued for its approach.[8] Longitudinal POCUS education through provincial rounds and conferences helps solidify the culture of a POCUS-integrated practice.

“It was really the HOUSE course … that kickstarted us big time. You could pick and choose what you want to learn. You learn as a group, and you learn in community. It’s you learning with the people that you’re going to be continuing to work with, and you’re all taking a common course in community with your own machines. If you do it on [your] machines in [your] town, you’re golden.” (Physician)

Administrative and system-level support: The local administrator worked alongside health care providers to support POCUS use and ultrasound acquisition. The administrator described that role as “an enabler of [the] physician group” and as being “able to get [the group] through the bureaucracy.” For example, the administrator deferred to the local physicians in the selection process of purchasing a new POCUS unit and then stepped in to ensure the procedures for device sterilization were developed in a way that minimized clinician workload. Northern Health, the regional health authority, was also supportive.

“[The local administrator is] incredible. … We need to give kudos and thanks to really good administrators … [with] openness to just let it flourish and not get in the way.” (Physician)

“We’re the size of France, and we have less than half a million people. Geographically, we’ve always been spread out. Northern Health, I think, is … doing pretty good as far as being innovators.” (Administrator)

Learning and collaboration: Positive aspects of the culture of medicine on Haida Gwaii were highlighted by all three study participants. Local physicians, allied health professionals, and administrators all work together to foster a collaborative and supportive approach, where asking for help is encouraged. Medical learners also seek out electives on Haida Gwaii because of its reputation as a hub for leading POCUS users, innovators, and teachers. As physicians teach the ongoing wave of new learners, a culture develops of POCUS being integral to family practice.

“We’re a small site … we’re the smallest maternity program in British Columbia, we’re the smallest systemic IV therapy BC Cancer site in the province. There’s a reason why these GPs … punch heavier than their weight limit. Not only are they invested in the community … but they also are invested in providing better patient care.” (Administrator)

“I noticed that they also reached out to the broader medical community if they saw something that they weren’t sure about. … They would ask me ‘Can I send this off?’ So they were able to get more input, and that’s without me leaving Haida Gwaii. That whole part just enhances care.” (Patient)

“You know, we know each other’s skills and support each other well, and there’s no shyness around connecting with each other for that.” (Physician)

“Every single [resident] wants and craves as much ultrasound as possible. … If I have a case that’s interesting, I’ll grab the resident no matter where they are … have them come in and do it with me. … It’s the number one learning thing that they say, because we’re kind of known for ultrasound.” (Physician)

Patient and provider satisfaction: Both patients and physicians reported increased satisfaction with the addition of POCUS to the patient encounter. Physicians felt empowered by the extra knowledge gained through POCUS findings, and patients readily appreciated the many ways in which POCUS positively impacted their health care experience.

“We’re fortunate that we have access to that machine. … That really enhanced my care and enhanced treatment for me, so I think that’s pretty amazing for a little community that they’re able to do that.” (Patient)

“[My doctor] was able to share those images with the surgeon in Prince Rupert. … When I got there, the surgeon said it saved him a lot of time. … The images [he] had were adequate for him to be able to set me up for the surgery.” (Patient)

“You speed up healing, because at the moment you see them, you diagnose the problem and then you do a procedure right away. I mean, that’s amazing. It feels so good to be able to do that.” (Physician)

“You feel almost like a magician sometimes to be able to see inside. And like in 5 seconds you can see a problem, which it would [instead] take all these blood tests and lots of exams and guessing and tries to treat and see if they get better, and ultimately an ultrasound … [in] Prince Rupert.” (Physician)

Discussion

The use of POCUS on Haida Gwaii is an example of how grassroots-led innovation can arise to meet local needs in sustainable and impactful ways. The enthusiasm and vision of a physician champion, educational supports that are responsive to community needs, and clear-sighted administrative support led to the creation of a system of care that is cost-saving, provides better medical care, improves patient and provider satisfaction, and significantly enhances the provision of compassionate and patient-centred care on Haida Gwaii.

The innovative and valuable POCUS practice arose from the combination of the innovation itself, the right people, and the right level of system support to meet the needs of the community. This process has much more in common with an Indigenous world view than conventional approaches to scaling up health care services. It can be summarized by the Haida saying Gina 'waadluxan gud ad kwaagid (“Everything depends on everything else”). Needs and gaps in rural health care arise from local resource scarcity and geography and are unique to each community. These needs are intimately known to local providers and patients, and solutions to navigating these barriers should include local knowledge.

In this challenging time in health care, it is refreshing to see a medical community flourishing and a health care system becoming more compassionate. Some of the most vulnerable patients in our health care system, residents of an exceptionally isolated island, are benefiting from a readily available and cost-saving innovation that provides compassionate and closer-to-home care. This is an example of how rural health potato ethics—“cooperating in the service of whatever is necessary and actively learning whatever is needed to do so”[9]—can guide us in building a better, kinder, and more equitable health care system for everyone.

Study limitations

This study was not a comprehensive evaluation of the development of the POCUS program on Haida Gwaii, but rather an overview of key factors that led to its emergence and sustainability. It is possible that there are other aspects of the program that remain unexamined. Additionally, the program emerged from the confluence of locally based needs, providers, and administration; therefore, the specifics may not be generalizable to other sites.

Suggestions for future research

Further research into potato ethics as a driver in rural health care and innovation could be valuable for learning how we might further support the process of valuable innovation in rural medical communities and health care system transformation in general.

Funding

This research was made possible in part by funding provided by RCCbc and the Joint Standing Committee on Rural Issues through the Rural Physician Research Grant Program.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Nixon G, Blattner K, Koroheke-Rogers M, et al. Point-of-care ultrasound in rural New Zealand: Safety, quality and impact on patient management. Aust J Rural Health 2018;26:342-349. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12472.

2. Flynn CJ, Weppler A, Theodoro D, et al. Emergency medicine ultrasonography in rural communities. Can J Rural Med 2012;17:99-104.

3. Henwood PC, Mackenzie DC, Rempell JS, et al. A practical guide to self-sustaining point-of-care ultrasound education programs in resource-limited settings. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:277-285.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.04.013.

4. Kornelsen J, Ho H, Robinson V, Frenkel O. Rural family physician use of point-of-care ultrasonography: Experiences of primary care providers in British Columbia, Canada. BMC Prim Care 2023;24:183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-023-02128-z.

5. Wilkinson T, Bluman B, Keesey A, et al. Rural emergency medicine needs assessment, British Columbia, Canada, 2014-2015: Final report. UBC Rural Continuing Professional Development Program, 26 March 2015. Accessed 19 August 2024. https://ubccpd.ca/sites/default/files/documents/Full%20Report_BC%20Rural%20EM%20Study_Mar%2026%202015.pdf.

6. Sheppard G, Devasahayam AJ, Campbell C, et al. The prevalence and patterns of use of point-of-care ultrasound in Newfoundland and Labrador. Can J Rural Med 2021;26:160-168. https://doi.org/10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_61_20.

7. Morton T, Kim DJ, Deleeuw T, et al. Use of point-of-care ultrasound in rural British Columbia: Scale, training, and barriers. Can Fam Physician 2024;70:109-116. https://doi.org/10.46747/cfp.7002109.

8. Young K, Moon N, Wilkinson T. Building point-of-care ultrasound capacity in rural emergency departments: An educational innovation. Can J Rural Med 2021;26:169-175. https://doi.org/10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_65_20.

9. Fors M. Potato ethics: What rural communities can teach us about healthcare. J Bioeth Inq 2023;20:265-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-023-10242-x.

10. Hamza DM, Regehr G. Eco-normalization: Evaluating the longevity of an innovation in context. Acad Med 2021;96:S48-S53. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000004318.

11. Thompson Burdine J, Thorne S, Sandhu G. Interpretive description: A flexible qualitative methodology for medical education research. Med Educ 2021;55:336-343. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14380.

Dr Wilkinson is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Family Practice, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia. She practises rural emergency medicine in BC and is a member of the Rural Coordination Centre of BC (RCCbc). Mr Curran is the manager of research and physician engagement in the Interior Health Authority’s Research Department and a member of RCCbc. Dr Robinson is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Family Practice, Faculty of Medicine, UBC; a staff physician at Elk Valley Hospital in Fernie; the medical lead of the Hands-On Ultrasound Education Obstetrics program in the Division of Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, UBC; and a member of RCCbc. Ms Moon is a program manager for the Division of Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Ms Rozhenko is a research and events assistant for the Division of Continuing Professional Development, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Ms DeLeeuw is a rural research and project facilitator with the Interior Health Authority and RCCbc.