Early detection, lasting prevention: The significance of coronary artery calcium scores

ABSTRACT: Atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease leading to cardiovascular disease, is a major global health challenge. Coronary artery calcium scoring has emerged as a critical tool in assessing the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by quantifying calcified plaque in coronary arteries via computed tomography scans. Coronary artery calcium scoring has been integrated into multiple guidelines for superior risk stratification and personalized treatment approaches. We discusses the basic concept of coronary artery calcium scoring, its interpretation, and the advantages and limitations of incorporating it into cardiovascular risk assessment strategies.

Coronary artery calcium scoring is a valuable tool for refining cardiovascular risk assessment, particularly in intermediate-risk individuals.

Atherosclerosis, a type of chronic inflammation that is marked by the buildup of lipid-rich plaque within the walls of the arteries, is the leading cause of cardiovascular disease, including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral artery disease.[1] As the disease progresses, it can lead to unstable atherosclerotic plaque rupture, vascular narrowing, or blockage due to platelet aggregation and thrombosis, which results in acute cardiovascular disease.[2] This pathological process begins early in life and is influenced by genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. Historically, atherosclerosis was observed in ancient populations, thus underscoring its long-standing impact on human health.[1] Despite advances in medical interventions and preventive strategies, atherosclerosis remains a major global health burden, which highlights the significance of early detection and effective risk assessment.[3]

Coronary artery calcium scoring

Assessment and interpretation

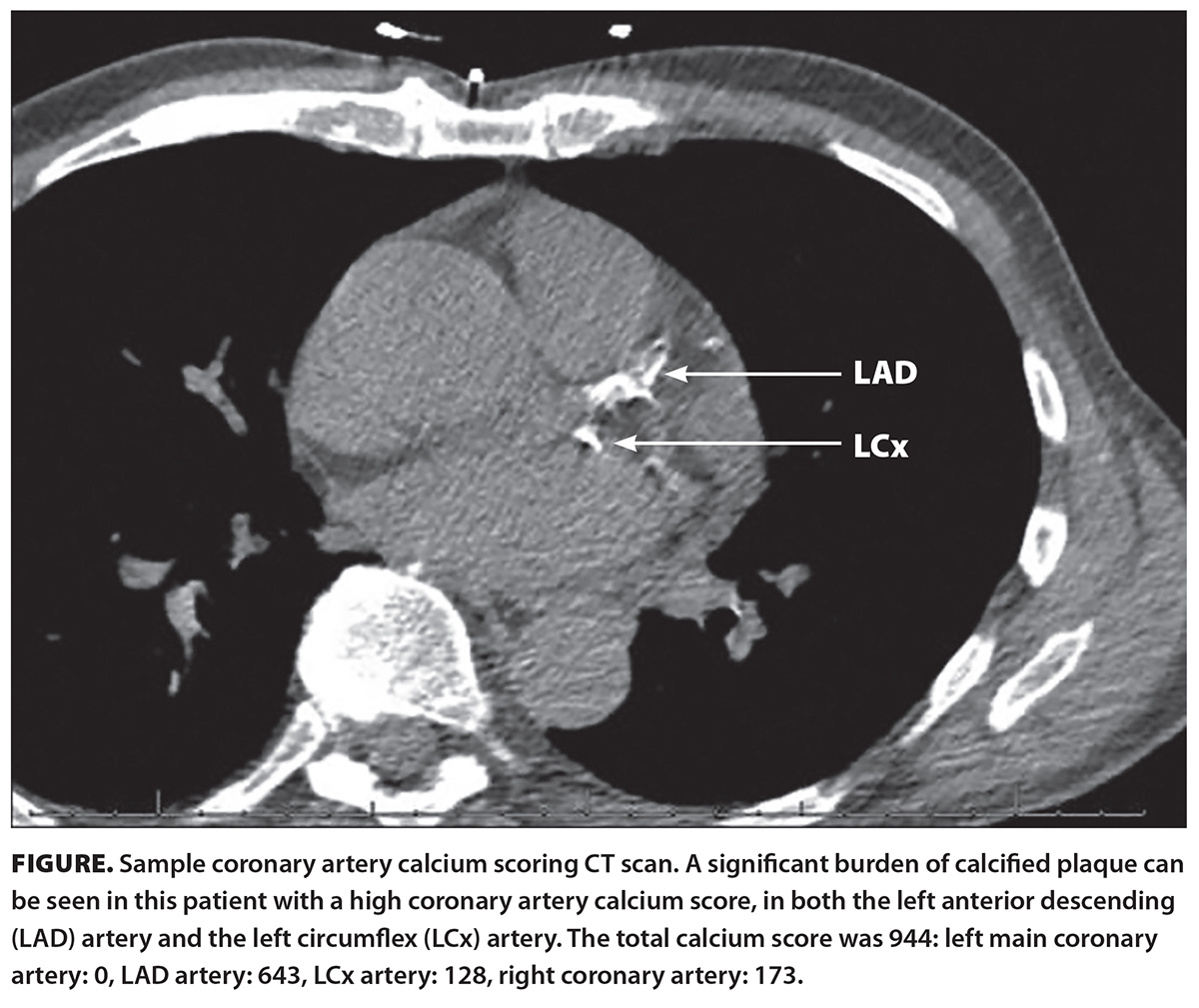

Coronary artery calcium scoring (CACS) is a noninvasive, specialized computed tomography (CT) scan of the heart that is used to assess the presence of calcified plaque in the coronary arteries [Figure]. It is used in evaluating the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in asymptomatic patients and offers a direct measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. It requires approximately 10 minutes of patient time in the procedure room. The radiation exposure of the scan does not exceed 1.0 mSv, which is comparable to that of a screening mammography (approximately 0.8 mSv) and lower than the yearly radiation exposure (i.e., natural environmental radiation) of approximately 3.0 mSv. CACS has been incorporated into various guidelines and criteria, where clinically suitable, including those of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and the Society of Thoracic Radiology.[4-8] The presence of calcium in the coronary arteries is strong evidence of atherosclerotic plaque.[9]

Coronary artery calcium scoring (CACS) is a noninvasive, specialized computed tomography (CT) scan of the heart that is used to assess the presence of calcified plaque in the coronary arteries [Figure]. It is used in evaluating the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in asymptomatic patients and offers a direct measure of subclinical atherosclerosis. It requires approximately 10 minutes of patient time in the procedure room. The radiation exposure of the scan does not exceed 1.0 mSv, which is comparable to that of a screening mammography (approximately 0.8 mSv) and lower than the yearly radiation exposure (i.e., natural environmental radiation) of approximately 3.0 mSv. CACS has been incorporated into various guidelines and criteria, where clinically suitable, including those of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography and the Society of Thoracic Radiology.[4-8] The presence of calcium in the coronary arteries is strong evidence of atherosclerotic plaque.[9]

The Agatston score is the most common method for detecting “regions of interest” in the coronary arteries that contain calcium deposits. Additionally, it helps determine the overall size of lesions that are larger than 1 mm2 and the highest calcific density of lesions that are more than 130 Hounsfield units.[10,11] The Hounsfield unit is a quantitative scale used to measure the density of various tissues on a CT scan.[12] The Agatston score is typically calculated using a CT data set with slice thickness ranging from 2.5 to 3.0 mm.[13] The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography developed the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS), which recommends reporting the total Agatston score and the regional distribution of CACS and provides risk stratification based on the quantified calcium score.[4]

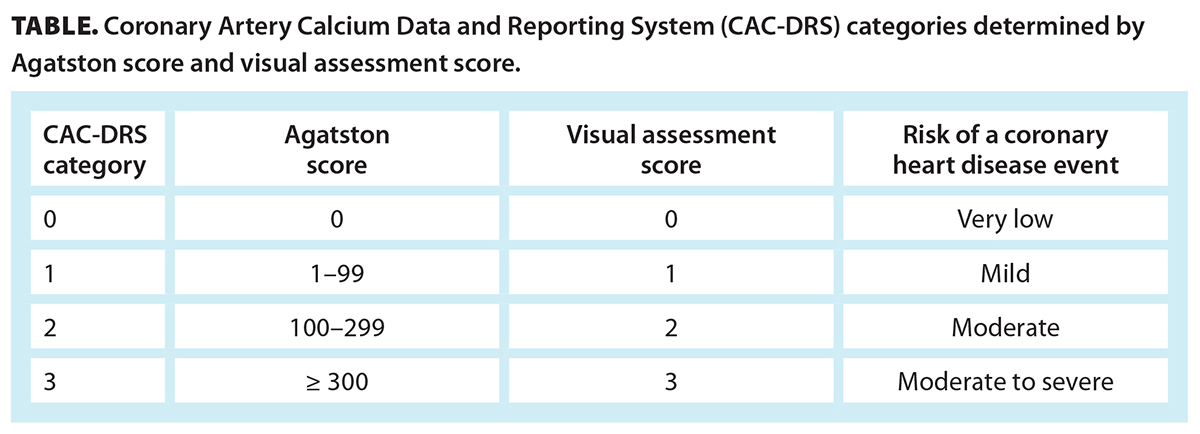

To support clinical decision making, the CAC-DRS aims to create a standardized method for reporting CACS findings on all noncontrast CT scans, regardless of the reason for the scan, and for providing recommendations for future patient management. The CAC-DRS categories, based on the Agatston score, aid understanding of heart attack risk, where scores above zero guide doctors to recommend lifestyle changes such as diet adjustment, exercise, and smoking cessation. When the score is zero, there is no calcified plaque and a very low risk of a coronary heart disease event [Table], which supports the decision to defer statin therapy while focusing on lifestyle modifications. A score from 1 to 99 indicates there is some calcified plaque and a mild risk of a coronary heart disease event, which supports considering statin therapy and addressing modifiable risk factors. Scores from 100 to 299 indicate there is a greater burden of calcified plaque and a moderate risk of a coronary heart disease event. Scores of 300 and higher suggest there is a large amount of calcified plaque and a moderate to severe risk of a coronary heart disease event. In this case, aggressive preventive interventions, such as moderate- to high-intensity statin therapy, the addition of other lipid-lowering medications and aspirin, and referral to a cardiologist, may be needed.[13-16] Additionally, CACS results are compared against reference data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis to determine the patient’s percentile, which indicates their coronary artery calcium burden relative to others in their demographic group.[17] Age, sex, and ethnicity/race are considered in estimating the percentile.

An initial scan for risk stratification is recommended at 42 years of age for men and 58 years of age for women who have no risk factors.[18] The recommended age is 6.4 years earlier for individuals who have diabetes.[18] This implies there is a 25% likelihood of a CACS result greater than zero in women with diabetes at age 50 and in men with diabetes at approximately age 36 to 37.[18] The initial step in evaluating asymptomatic patients for primary prevention is to determine their risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by referencing risk scores such as the Framingham Risk Score, the Reynolds Risk Score, and the Pooled Cohort Equations Risk Calculator.[19]

In British Columbia, CACS is not covered under the Medical Services Plan.[20] However, select hospitals may offer the test to patients at no cost, and private diagnostic laboratories provide it for a fee. Family physicians and specialists can order the test, provided it is supported by appropriate clinical indications and considerations.

Advantages and limitations

CACS is a superior tool for assessing cardiovascular risk compared with traditional risk factors and other markers, because it can help identify the patient group for therapeutic interventions, and it offers a highly personalized risk assessment. Additionally, it can enhance patient adherence to long-term treatment strategies, including dietary modifications, exercise regimens, and statin medications, which contributes to more effective and tailored health care.[21]

However, CACS has some limitations. It identifies only calcified plaque, not noncalcified (soft) plaque, and it does not differentiate between stable and unstable plaque. The composition of plaque is crucial to understanding the true risk of cardiovascular events.[3] Additionally, it may have limited predictive value in specific populations, such as younger individuals and those with diabetes. In these groups, the absence of coronary calcium does not necessarily mean there is a low risk of cardiovascular events, in part due to the potential for noncalcified plaque to be present.[18] CACS also does not provide detailed information about plaque morphology or the degree of stenosis in coronary arteries.[22] This may lead to a lack of precision in assessing the severity and clinical significance of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Last, while CACS has the potential to optimize risk stratification, the upfront cost of the procedure and subsequent follow-up testing may be a concern. The overall cost-effectiveness of integrating CACS into routine cardiovascular risk assessment needs careful consideration.[3]

Furthermore, CACS does not replace CT coronary angiography, especially in patients with concerning symptoms of coronary heart disease. CT coronary angiography performed noninvasively by administration of intravenous contrast provides direct visualization of the coronary artery lumen and is capable of detecting both noncalcified and calcified plaque. It assesses the anatomical severity of stenosis and is commonly used in symptomatic patients and those with abnormal exercise stress test results. Moreover, invasive coronary angiography allows for immediate therapeutic intervention, such as percutaneous coronary intervention or stenting, when necessary. Although CT coronary angiography provides greater anatomic detail and functional assessment, it is associated with higher radiation exposure and procedural risks compared with CACS. Therefore, while CACS is suitable for primary prevention and risk stratification, CT coronary angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing and managing obstructive coronary heart disease in symptomatic patients and those with high pretest probability.[16,23]

Despite these limitations, CACS is a useful tool for assessing atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, particularly in certain populations. However, health care professionals must be aware of these limitations and use CACS in conjunction with other clinical information for a more comprehensive risk evaluation.

The power of zero

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis indicated that a CACS result of zero is the most significant negative risk marker among various clinical and imaging tests for cardiovascular risk. Low-risk patients with a CACS result of zero had a very low probability of developing coronary heart disease and of other cardiovascular disease events over a 10-year follow-up period.[24] The score significantly reduced the posttest risk assessment compared with other risk indicators, such as high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and carotid intima-media thickness. Furthermore, the absence of coronary artery calcification, indicated by a CACS result of zero, led to the most accurate significant downward adjustment of cardiovascular risk assessment. Thus, individuals initially assessed as having moderate or high risk based on traditional factors could have their risk downgraded after a CACS result of zero and thus potentially avoid unnecessary treatments such as statin therapy.[24]

Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines

In Canada, CACS is used selectively rather than for routine screening. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society’s 2021 guidelines recommend CACS scanning for individuals age 40 and older who are at intermediate risk (10.0% to 19.9% based on risk scores such as the Framingham Risk Score) and for whom treatment decisions are uncertain. In these individuals, CACS can help refine cardiovascular risk and guide decisions regarding statin therapy. Specifically, the presence of a CACS result greater than zero can prompt the use of more aggressive prevention strategies, such as statin therapy, in those who may not have otherwise been recommended for treatment.[6]

Conclusions

CACS is a valuable tool for refining cardiovascular risk assessment, particularly in intermediate-risk individuals. The integration of novel biomarkers alongside CACS may further enhance early detection and personalized prevention strategies and thus ultimately reduce the burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Fan J, Watanabe T. Atherosclerosis: Known and unknown. Pathol Int 2022;72:151-160. https://doi.org/10.1111/pin.13202.

2. Zhu Y, Xian X, Wang Z, et al. Research progress on the relationship between atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules 2018;8:80. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom8030080.

3. Cheong BYC, Wilson JM, Spann SJ, et al. Coronary artery calcium scoring: An evidence-based guide for primary care physicians. J Intern Med 2021;289:309-324. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13176.

4. Hecht HS, Blaha MJ, Kazerooni EA, et al. CAC-DRS: Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System. An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018;12:185-191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2018.03.008.

5. Shreya D, Zamora DI, Patel GS, et al. Coronary artery calcium score—A reliable indicator of coronary artery disease? Cureus 2021;13:e20149. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.20149.

6. Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:1129-1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.03.016.

7. Voros S, Rivera JJ, Berman DS, et al. Guideline for minimizing radiation exposure during acquisition of coronary artery calcium scans with multidetector computed tomography. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2011;5:75-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcct.2011.01.003.

8. Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, et al. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:434-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.027.

9. Mohan J, Bhatti K, Tawney A, et al. Coronary artery calcification. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

10. Burge MR, Eaton RP, Comerci G, et al. Management of asymptomatic patients with positive coronary artery calcium scans. J Endocr Soc 2017;1:588-599. https://doi.org/10.1210/js.2016-1080.

11. Neves PO, Andrade J, Monção H. Coronary artery calcium score: Current status. Radiol Bras 2017;50:182-189. https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-3984.2015.0235.

12. DenOtter TD, Schubert J. Hounsfield unit. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

13. Kumar P, Bhatia M. Coronary artery calcium data and reporting system (CAC-DRS): A primer. J Cardiovasc Imaging 2023;31:1-17. https://doi.org/10.4250/jcvi.2022.0029.

14. Obisesan OH, Osei AD, Uddin SMI, et al. An update on coronary artery calcium interpretation at chest and cardiac CT. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging 2021;3:e200484. https://doi.org/10.1148/ryct.2021200484.

15. Miedema MD, Duprez DA, Misialek JR, et al. Use of coronary artery calcium testing to guide aspirin utilization for primary prevention: Estimates from the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014;7:453-460. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000690.

16. Lima MR, Lopes PM, Ferreira AM. Use of coronary artery calcium score and coronary CT angiography to guide cardiovascular prevention and treatment. Ther Adv Cardiovasc Dis 2024;18:17539447241249650. https://doi.org/10.1177/17539447241249650.

17. McClelland RL, Jorgensen NW, Budoff M, et al. 10-year coronary heart disease risk prediction using coronary artery calcium and traditional risk factors: Derivation in the MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) with validation in the HNR (Heinz Nixdorf Recall) study and the DHS (Dallas Heart Study). J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1643-1653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.035.

18. Dzaye O, Razavi AC, Dardari ZA, et al. Modeling the recommended age for initiating coronary artery calcium testing among at-risk young adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 2021;78:1573-1583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.08.019.

19. Lloyd-Jones DM, Braun LT, Ndumele CE, et al. Use of risk assessment tools to guide decision-making in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation 2019;139:e1162-e1177. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000638.

20. Government of British Columbia. Services not covered by the Medical Services Plan (MSP). Updated 23 January 2020. Accessed 23 January 2020. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/health-drug-coverage/msp/bc-residents/benefits/services-not-covered-by-msp.

21. Blaha MJ, Silverman MG, Budoff MJ. Is there a role for coronary artery calcium scoring for management of asymptomatic patients at risk for coronary artery disease?: Clinical risk scores are not sufficient to define primary prevention treatment strategies among asymptomatic patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2014;7:398-408. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000341.

22. Bergström G, Persson M, Adiels M, et al. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis in the general population. Circulation 2021;144:916-929. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.055340.

23. Malik TF, Tivakaran VS. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2018.

24. Blaha MJ, Cainzos-Achirica M, Greenland P, et al. Role of coronary artery calcium score of zero and other negative risk markers for cardiovascular disease: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation 2016;133:849-858. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018524.

Dr Aldarmasi is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Medicine at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and a clinical fellow in the Cardiac Rehabilitation and Prevention Program at the University of British Columbia. Dr Ignaszewski is a clinical associate professor at UBC. Dr Taylor is a clinical associate professor at UBC and medical director for the Cardiac Rehabilitation Program at St. Paul’s Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Moroj A. Aldarmasi, maldarmasi@kau.edu.sa.