Cannabis use by adolescents: Practical implications for clinicians

It is not clear whether marijuana will turn out to be medicinal at all. Looking for data that might shed some light on the question, the author undertook a review of recent literature and performed a qualitative structured analysis of narratives from 100 adolescent patients who smoke cannabis daily.

On 17 October 2018, Canada joined nine American states and Uruguay by enacting legislation to legalize, regulate, and restrict access to cannabis for nonmedical purposes. So far, legalization has had mixed reviews.

The good news is that teen use appears to be dropping, now that there are serious penalties for selling to minors.[1] The rate of violent crime has decreased by 10%,[2] and tax revenues have increased, giving some states over US$100 million annually to spend on programs for mental health and addiction.[3]

The bad news is that there are more accidental overdoses and deaths,[4] more cannabis-related convictions for driving under the influence, and more fatal crashes.[5] Furthermore, high taxes on cannabis have left plenty of room for the black market to continue to thrive.[6]

The most troubling trend is that overall use is increasing in the US.[7] In Colorado, where there are more marijuana dispensaries than there are Starbucks and McDonald’s combined, legal sales increased by 33% in the last year and by 700% since 2012.[8] This makes the US cannabis market larger than that for coffee, wheat, or corn[9] and explains why the three largest cannabis stocks now have a market capitalization of over US$30 billion and growing.[10]

Cannabis usage

Cannabis is the most commonly used illicit drug globally. According to Statistics Canada, nationally, 14% of Canadians aged 15 years and older reported some use of cannabis products in the surveyed period (February to April 2018) (Figure 1).[11] Approximately 8% of all users used some form of cannabis daily or weekly.[11] These are the important metrics because they are most closely correlated to health risks.[12,13]

If you’re looking at this scientifically, you might have an issue with the correlation of use to health risks, because one “daily user” may smoke all day, every day, and another “daily user” may have a few puffs before bed. Nevertheless, the metric of “how many times a week do you smoke” is still valuable, because it allows you to subdivide users into three groups:

- Recreational: less experienced, use less than once per week, more likely to present with drug-induced psychosis and panic attacks.

- Social: moderately experienced, use mostly on weekends (1 to 2 times per week), more likely to experience short-term impairment in cognition and productivity, least likely to present to you clinically.

- Medicinal: most experienced, self-medicate physical but also psychological symptoms, most likely to experience withdrawal and long-term sequelae such as amotivation and chronic depression.

Understanding cannabis

If we are to make any sense of cannabis clinically, we must first appreciate what the drivers are for youth using cannabis, and why they so passionately defend its use.

The North Shore ADHD and Addiction Clinic, based in North Vancouver, British Columbia, provides longitudinal care under the Medical Services Plan. To help better understand cannabis use among adolescents, we identified 100 charts in our clinic’s EMR of patients who met the following criteria:

- Age: 13 to 25 years old.

- Diagnosis: Cannabis use disorder, DSM-5 304.3.

- Date of first visit: January 2015 to October 2017.

- Inclusion criteria: Self-reported smoking cannabis > 20 days per month.

- Positive drug screen for cannabinoids.

We used qualitative content analysis using a standard approach.[14] Patients were asked standardized questions as part of a comprehensive mental health and addiction assessment at our clinic.

The data were anonymized and deidentified of any demographic information and exported from our EMR, Accuro, to a spreadsheet and then into narrative analysis software, QSR NVivo 11 for Mac. Coding and thematic organization was done by two blinded researchers from our clinic. Numeric data fields included a random numerical identifier and number of days smoked per month. Narrative fields included type of cannabis smoked and patient-rated Cannabis indica and Cannabis sativa positive and negative effects.

Clinical scenario: The reality of heavy cannabis use

Monday morning, you walk into your office to meet an intelligent 20-year-old postsecondary student. She has been struggling with depression and difficulty concentrating, and is now on academic probation. She is brought to you by supportive parents after a brief episode of drug-induced paranoid delusions. Upon further questioning, she tells you that she finds school boring and she spends most of her waking hours on her phone, playing video games, and smoking cannabis.

You, like most physicians you know, after summing up the available data, have developed a generally negative view on cannabis as a cure-all, are avoiding discussing your views with patients because you don’t feel well-enough informed, or are taking a wait-and-see approach.

Now is the time to take a deep dive into cannabis.

Cannabis botany

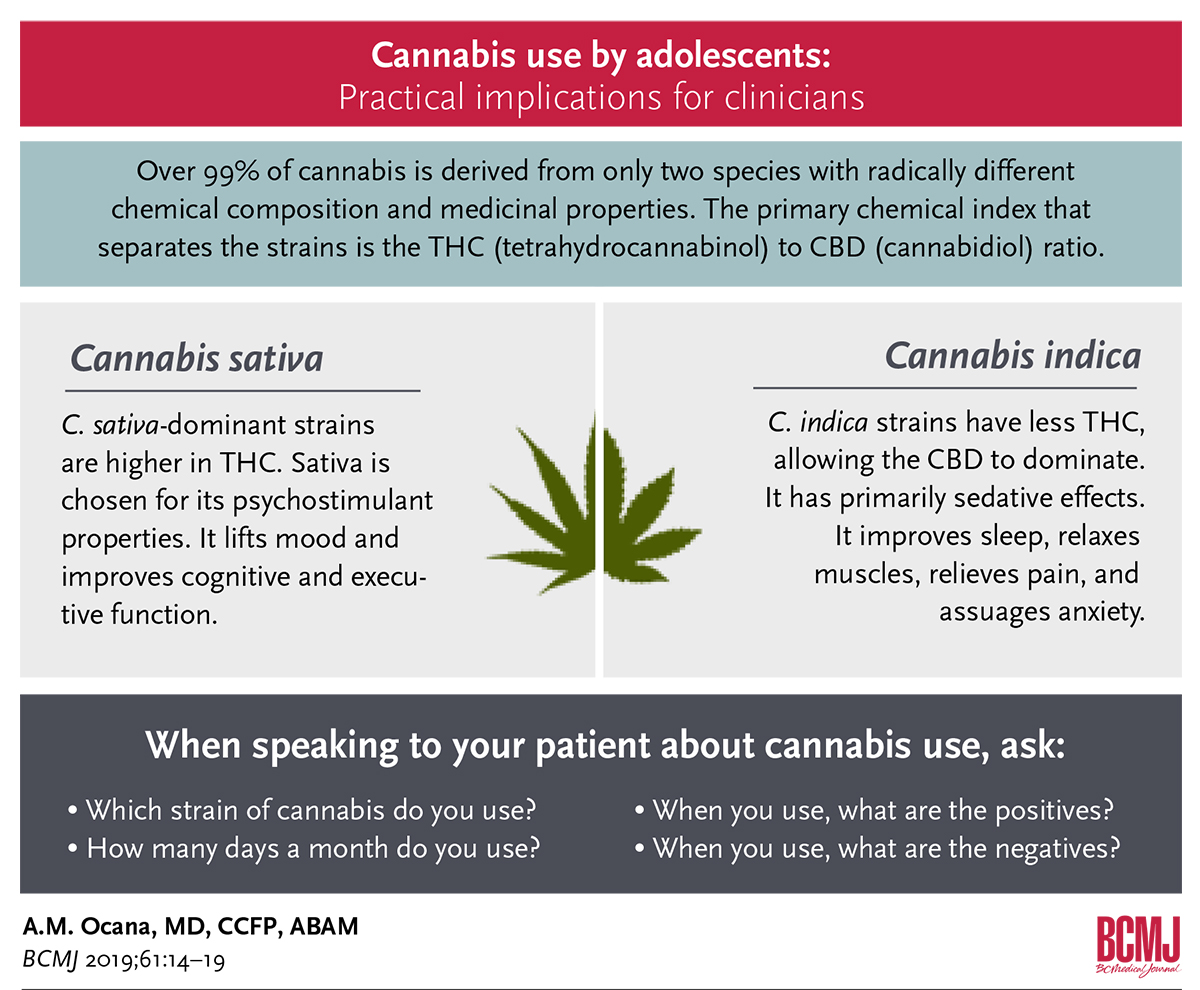

Despite the huge variety of cannabis available, over 99% is derived from only two species with radically different chemical composition and medicinal properties. They are essentially polar opposites: C. sativa, which is a stimulant, and C. indica, which has primarily sedative effects.

While extensive cross-breeding has entangled the species over the years, phytochemical, genetic, and clinical research continues to support their separation.[15]

Cannabis chemistry

The primary chemical index that separates C. sativa and C. indica is the THC (tetrahydrocannabinol) to CBD (cannabidiol) ratio. C. sativa-dominant strains are higher in THC. C. indica strains have relatively less THC effect, allowing the CBD effect to dominate.[15]

Results from US federal drug detection laboratories in Colorado indicate that the average C. sativa strain has a THC to CBD ratio of 250:1, whereas the average C. indica strain has a ratio of 100:1.

Hybrids vary in their composition of THC, CBD, and other cannabinoids. They are referred to by the dominant cannabinoid ratio inherited from their lineage, and they are often given colorful names such as Acapulco Gold, Northern Lights, or Purple Kush.[16] Even today, no one really knows if THC and CBD are the most relevant cannabinoids. Significant data support the inclusion of multiple other active chemicals such as cannabitriol and terpenes in some strains.[17]

Cannabis neurobiology

The different strains of cannabis exert their psychoactive effects relative to which cannabinoid receptors are stimulated or inhibited. The CB1 receptor is densely distributed predominantly throughout the brain, while the CB2 receptor affects immune tissues and cells in the periphery.

These receptors subsequently modulate neurotransmission in multiple circuits:

- The increase in peripheral serotonergic tone is associated with pain relief, sedation, anxiolysis, and in the extreme, hallucinations.

- The stimulation of mesolimbic dopaminergic circuits is associated with the reward and psychostimulant effects.[18]

- The decrease in glutamatergic neurotransmission and the stimulation of GABA and various other permutations of circuits are associated with antinausea, mood-stabilizing, and antiseizure properties. Glutamate inhibition also explains how C. indica produces the “turning off my brain” effect that is so prized for its ability to promote sleep.[19]

Cannabis as self-medication

Adolescents don’t choose to become addicted to cannabis. However, when they experience improved sleep or mood, or lessened pain, cannabis becomes their best friend and self-medication of choice, the synthesis of which usually cements their opposition to further discussion.

Self-medication is the most consistent theme in our patients’ narratives. As opposed to recreational users, chronic daily users specifically modulate three key factors to obtain their desired therapeutic effects:

- Strain (C. sativa versus C. indica)

- Amount used

- Day or evening use

Specifically, C. sativa is chosen for its psychostimulant properties. It lifts mood and improves cognitive and executive function. C. indica is generally experienced as sedating. It improves sleep, relaxes muscles, relieves pain, and assuages anxiety (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

This narrative from a 19-year-old daily cannabis user is typical of the cohort: “I smoke sativa during the day. It is more stimulating and it helps me get things done. I smoke indica before bed. It relaxes my muscles and eventually helps me sleep. Psychologically, it slows down my thinking process and I feel subtly happier, and calm. The problem is, I wake up in a daze and I need a coffee to get out the door.”

Practical implication for clinicians

These two strains of cannabis have radically different chemical composition, medical properties, and neurobiological effects. They are essentially opposites, a crucial insight unknown by most clinicians.[15] Therefore, it behooves clinicians to know the difference and specify the strain. Similarly, research that has not segmented the data by strain are uninterpretable.

When speaking to your patient about cannabis use, ask:

- Which strain of cannabis do you use?

- How many days a month do you use?

- When you use, what are the positives? What are the negatives?

In doing so, you will gain credibility, laying the foundation for an ongoing therapeutic alliance.

Heavy cannabis use is associated with multiple comorbidities. Screening for depression, anxiety, panic, ADHD, trauma, psychosis, and mania may help tease out the underlying cause for the affect dysregulation for which cannabis is the cure. A family history of substance use is not uncommon.[20]

Dealing with misinformation

As explained in the new video on the CMA website (www.youtube.com/watch?v=fMsypYm9Kho), “Cannabis may be legal, but it is not harmless because it can hurt your health, cause dependence, impair attention, memory, and ability to make decisions, and make it hard to think, study, work, or cope.”[21,22] Listing these facts to your patients will not likely be very fruitful because they may be operating under a number of false beliefs and rationalizations that contradict them. The three most commonly held false beliefs about cannabis are that it is not harmful, it is not addictive, and there are no withdrawal symptoms.

False belief 1: Cannabis is not harmful

The misperception that cannabis is not harmful is captured by Monitoring the Future, a cross-sectional survey of more than 250 000 American high school students that documents the steady decrease in perceived harmfulness of cannabis in the last 10 years.[23]

It’s true that, relatively speaking, the morbidity, mortality, and economic harm to society associated with other legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco dwarf those associated with marijuana use.[24] However, it’s not relative harm that matters, but absolute harm, specifically to the most vulnerable—adolescents with mental health challenges.

The first and most expensive harm of cannabis legalization, from the point of view of health authorities, will be felt in emergency departments from the increase in poisoning, adverse events, and drug-induced psychosis. Researchers in Colorado found that the annual number of visits associated with a cannabis-related diagnostic code, accompanied by a positive marijuana urine drug screen, more than quadrupled between 2005 and 2014 (from 146 to 639).[25]

That trend will continue because legalization has dramatically increased the number of novice users, who are more likely to underestimate the potency of their cannabis and are therefore responsible for most cannabis-induced ER visits. The symptoms exhibited by these patients include nausea, vomiting, suspicion/paranoia, agitation, psychosis, and occasional respiratory depression, which, in combination with other drugs, can be life threatening.

Edible cannabis products pose the greatest risk to the inexperienced.[26] Their presentation is purposefully misleading. They are often unlabeled and packaged as candy in the shape of lollipops or gummy bears. Health Canada, in consultation with experts, has published guidelines that will require edibles to be sold in fixed dosages and, for the moment, edibles remain off the market.[27]

Fixed dosages unfortunately do not make much difference to novices who still have not titrated dose to effect. Getting edibles right is difficult for any user because the cannabinoids in edibles are absorbed through the GI tract, thus having a slower onset and longer-lasting effects. Given no way to predict the time of onset or gauge the intensity of effect, first-time users often eat too much initially or do not wait long enough for effects to take place before having more, sometimes leading to a hospital visit. It would be helpful to know, and as such be able to warn users about, which strains are particularly psychosis-inducing.

False belief 2: Cannabis is not addictive

The 20-year-old patient in our clinical scenario may point out that only 10% of those who experiment with cannabis get addicted to it—less than cocaine, methamphetamine, or even alcohol.[28] This is true, but half of all those who use cannabis regularly become heavy users. And your patient by her own admission is a heavy user. You ask whether she experiences any negative effects, and she admits to the following:

- Significant impairment in her cognition, associated with social anxiety, academic underfunction, and decreased occupational productivity, at least in the short term.

- Noticeable dysphoria upon quitting, which prompted her return to continued use.

Since continued use (despite negative consequences) is the de facto criteria for a substance use disorder, it would be fair to say that cannabis is addictive after all.[29]

This would be a good time to discuss SMART goals with your patient, an acronym that refers to patient-initiated changes that are Specific, Measurable, Agreed upon, Realistic, and Time based. Motivational interviewing might also be effective because it encourages accountability and exploration of patient motivation for using versus quitting.[30]

False belief 3: There is no withdrawal from cannabis

True, the experience of withdrawal is often less with cannabis than with other drugs. Cannabinoids are fat soluble and therefore stored in adipose tissue, including that of the testes and ovaries. Cannabis also has active metabolites, the combination of which results in slower decay of serum levels of cannabinoids, thus decreasing the experience of withdrawal.[31]

However, the experience of withdrawal has changed over the years as the potency of cannabis has increased markedly. Forty years ago the average potency of smoked flower was 3% to 5% THC. In Colorado in 2015, the average THC level in legal cannabis was 18.7%, with some products containing 30%. Shatter, a crystalized cannabis extract, is 80% THC.[32] Higher potency cannabis results in higher serum cannabinoids levels, some of which decay quickly upon cessation of use, thus increasing the experience of withdrawal, dependence, addiction, and relapse.[32] At the moment, no one knows which strains are the most addictive.

Here is a typical narrative from a daily cannabis user who recently quit: “When I cut pot out completely, I became more anxious and found that I could not sleep, and that bothered me. When I started smoking again, I felt better, but then I felt like I was addicted and that’s not really what I wanted.”

Addressing adolescent cannabis use disorder is a process. Inviting your patient to two or three further visits will give you the time to align and address the challenges together.

Managing the impact of cannabis legalization

Overall Canada’s approach to cannabis legalization gets high scores for prevention and harm reduction. Approaching this as a public health challenge, the federal government has sponsored cannabis education flyers, youth-oriented television ads, and videos on the Internet. The CMA has partnered with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and a number of other entities and has created sensible guidelines for safer consumption.[33] Local programs in British Columbia have done a masterful job of bringing mental health concepts into schools and creating a system of youth-oriented mental health clinics, known as Foundry.

What Canada lacks, however, is a cohesive information technology (IT) system to measure and compare the impact of different strains of cannabis, or the impact of treatment with cannabis compared with other interventions (e.g., the benefits of cannabis versus opiates to control chronic pain). More importantly, according to Harvard economics professor Michael Porter, there is no way to compare the economic benefits of different interventions until we can collect patient-centric metrics—at the point of care, across the entire care journey.[34] Without such predictive analytics, it is impossible to determine, for example, the best approach to the opiate crisis. Should we prioritize training more addiction specialists, teaching firefighters to administer naloxone, paying family physicians to integrate mental health into workflow, or supporting the patient medical home?

At the moment, mental health and addiction present an expensive, painful, and unmanaged burden on society. We could probably do better if we knew what to do.

Acknowledgments

Sections of this article were published in Addiction Medicine and Therapy (https://medcraveonline.com/MOJAMT/MOJAMT-05-00119.php).

Competing interests

None declared.

hidden

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

1. Cerdá M, Wall M, Feng T, et al. Association of State Recreational Marijuana Laws with Adolescent Marijuana Use. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171:142-149.

2. Heuberger B. Despite claims, data show legalized marijuana has not increased crime rates. 22 March 2017. Accessed 28 October 2018. www.coloradopolitics.com/news/despite-claims-data-show-legalized-marijuana-has-not-increased-crime/article_64dd25c9-bcb1-5896-8c62-735e953da28a.html.

3. Williams T. Marijuana tax revenue hit $200 million in Colorado as sales pass $1 billion. 12 February 2017. Accessed 28 October 2018. www.marketwatch.com/story/marijuana-tax-revenue-hit-200-million-in-colorado-as-sales-pass-1-billion-2017-02-10.

4. Wang GS, Le Lait MC, Deakyne SJ, et al. Unintentional pediatric exposures to marijuana in Colorado, 2009-2015. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:e160971.

5. Migoya D. Traffic fatalities linked to marijuana are up sharply in Colorado. Is legalization to blame? Denver Post. 25 August 2017. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.denverpost.com/2017/08/25/colorado-marijuana-traffic-fatalities.

6. Saminather N. Why Canada’s pot legalization won’t stop black-market sales. Reuters. 7 June 2018. Accessed 18 December 2018. https://ca.reuters.com/article/businessNews/idCAKCN1J40FS-OCABS.

7. Kerr DCR, Bae H, Phibbs S, Kern AC. Changes in undergraduates’ marijuana, heavy alcohol and cigarette use following legalization of recreational marijuana use in Oregon. Addiction 2017;112:1992-2001.

8. Colorado Department of Revenue. Marijuana sales report. 12 January 2018. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.colorado.gov/pacific/revenue/colorado-marijuana-sales-reports.

9. Grant K. Cannabis investing: 2 of the easiest stocks to buy to play the legal weed boom. 1 April 2018. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.thestreet.com/story/14539600/1/how-to-invest-in-cannabis-with-stocks.html.

10. Smallcap Power. Canada’s Liberal government has paved the way for recreational use in the near future, boosting the value of these Canadian marijuana stocks or pot stocks. 18 October 2018. Accessed 28 October 2018. https://smallcappower.com/canadian-marijuana-stocks-pot-stock.

11. Statistics Canada. National cannabis survey, first quarter 2018. 27 April 2018. Accessed 26 October 2018. www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/180418/dq180418b-eng.htm.

12. Health Effects of Cannabis. Government of Canada. Accessed 5 November 2018. www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/campaigns/27-16-1808-Factsheet-Health-Effects-eng-web.pdf.

13. Broyd SJ, van Hell HH, Beale C, et al. Acute and chronic effects of cannabinoids on human cognition—a systematic review. Biol Psychiatry 2016;79:557-567.

14. Forman J, Damschroder L. Qualitative content analysis. In: Jacoby L, Siminoff LA, editors. Empirical Methods for Bioethics: A Primer (Advances in Bioethics, Volume 11). Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2007. pp. 39-62.

15. Madras BK. Update of cannabis and its medical use. Accessed 18 December 2018. https://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/6_2_cannabis_update.pdf.

16. Rappold RS. Year 1 of legal marijuana: Lessons learned in CO. WebMD Health News. 6 November 2014. Accessed 28 October 2018. www.webmd.com/brain/news/20141106/legal-marijuana-year-one#1.

17. Elsohly MA, Slade D. Chemical constituents of marijuana: The complex mixture of natural cannabinoids. Life Sci 2005;78:539-548.

18. Rigucci S, Xin L, Klauser P, et al. Cannabis use in early psychosis is associated with reduced glutamate levels in the prefrontal cortex. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2018;235:13-22.

19. Gonzalez R. Acute and non-acute effects of cannabis on brain functioning and neuropsychological performance. Neuropsychol Rev 2007;17:347-361.

20. Turner SD, Spithoff S, Kahan M. Approach to cannabis use disorder in primary care. Can Fam Phys 2014;60:801-808.

21. Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: An integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:286-293.

22. Cerdá M, Moffitt TE, Meier MH, et al. Persistent cannabis dependence and alcohol dependence represent risks for midlife economic and social problems: A longitudinal cohort study. Clin Psychol Sci. 2016;4:1028-1046.

23. Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the future, national survey results on drug use: 1975-2017. 2017 Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2017.pdf.

24. Meier MH, Caspi A, Cerdá M, et al. Associations between cannabis use and physical health problems in early midlife: A longitudinal comparison of persistent cannabis vs tobacco users. JAMA Psychiatry 2016;73:731-740.

25. Science Daily. ER visits related to marijuana use at a Colorado hospital quadruple after legalization. 4 May 2017. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/05/170504083114.htm.

26. Nicholson K. Spike in cannabis overdoses blamed on potent edibles, poor public education. CBC News. 28 August 2018. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.cbc.ca/news/health/cannabis-overdose-legalization-edibles-public-education-1.4800118.

27. Government of Canada. Legalizing and strictly regulating cannabis: The facts. 13 March 2018. Accessed 5 November 2018. www.canada.ca/en/services/health/campaigns/legalizing-strictly-regulating-cannabis-facts.html.

28. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services, et al. Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed tables. Accessed 28 October 2018. www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015/NSDUH-DetTabs-2015.htm.

29. Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: Recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry 2013;170:834-851.

30. Psychology Today. Motivational interviewing. Accessed 18 December 2018. www.psychologytoday.com/ca/therapy-types/motivational-interviewing.

31. Greene MC, Kelly JF. The prevalence of cannabis withdrawal and its influence on adolescents’ treatment response and outcomes: A 12-month prospective investigation. J Addict Med 2014;8:359-367.

32. Walton AG. New study shows how marijuana’s potency has changed over time. Accessed 4 February 2018. www.forbes.com/sites/alicegwalton/2015/03/23/pot-evolution-how-the-makeup-of-marijuana-has-changed-over-time/#2b989ca559e5.

33. CAMH. Canada’s lower-risk cannabis use guidelines. Accessed 22 July 2018. www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs---reports-and-books---research/canadas-lower-risk-guidelines-cannabis-pdf.pdf.

34. Porter ME. Redefining health care: Creating value-based competition on results. Atlantic Econ J 2007;35:491-501.

hidden

Dr Ocana is an addiction medicine specialist accredited by the American Board of Addiction Medicine and cofounder of the North Shore ADHD and Addiction Clinic.