The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child in Vancouver’s inner city

Results from a survey exploring an inner-city community’s knowledge of and experience with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child

In 1989, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) [Figure 1].[1] The UNCRC was informed by previous declarations, including the 1924 Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child and the 1959 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child.[1] These early documents were limited in scope, with 5 and 10 articles, respectively, and they did not define the start or end of childhood. The much-expanded 54 articles of the UNCRC outline the rights of all humans under the age of 18, or the age of majority, to fully develop their personalities; assume community responsibilities; and live with equality, dignity, and peace.[1]

In 1989, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) [Figure 1].[1] The UNCRC was informed by previous declarations, including the 1924 Geneva Declaration of the Rights of the Child and the 1959 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of the Child.[1] These early documents were limited in scope, with 5 and 10 articles, respectively, and they did not define the start or end of childhood. The much-expanded 54 articles of the UNCRC outline the rights of all humans under the age of 18, or the age of majority, to fully develop their personalities; assume community responsibilities; and live with equality, dignity, and peace.[1]

The UNCRC is significant because it recognizes children as people with rights who play an active role in their own well-being, as opposed to passive objects in need of adult protection.[2-4] The UNCRC is widely approved, with 196 countries ratifying it.[1] Despite this, the UNCRC does have limitations. It has been criticized for assuming Western ideological notions of childhood as universal, and directly linking UNCRC articles and implementation to indicators of a child’s well-being remains controversial.[4,5]

The UNCRC in Canada

The Canadian government ratified the UNCRC in 1991, with two reservations.[4] The first reservation concerned article 21, which suggested that children might be adopted by caregivers in other countries, potentially limiting their access to their culture, language, and religion (articles 20 and 30). The second reservation pertained to article 37 (detention), because detaining children separately from adults may not always be feasible in the context of the Canadian judicial system. Today, the UNCRC informs areas of Canadian law such as citizenship and divorce; Indigenous law at the federal level; and education, health care, and child welfare at the provincial and territorial level.[4,6]

Canadian delegates played a key role in drafting the UNCRC, and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney co-chaired the subsequent World Summit for Children in 1990; however, Canada still fails to honor the rights of vulnerable children and youth.[6]

The UNCRC in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside and associated inner-city community

In collaboration with Elders and community members, we developed a survey, including a visual summary of the UNCRC and numeric, descriptive, smiley-face Likert scales, to investigate individuals’ experiences with knowledge and access to child and youth rights in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (DTES) and associated inner-city community. The survey was approved by the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (UBC REB #H20-00987).

After exploring participants’ overall familiarity with the UNCRC, participants were asked to consider access to specific UNCRC articles: article 6 (potential), article 12 (views), article 23 (disability), article 24 (health), article 28 (access to education), article 29 (aims of education), article 31 (rest, play, and culture), and article 42 (knowledge) [Table 1]. Elders and community members chose to highlight these articles in our dialogues due to their significance in the community context.

Between September 2020 and November 2021, we used convenience sampling to recruit 45 DTES and associated inner-city community members to participate in the survey (18 youth, 16 caregivers, and 11 staff members). Participant demographics are included in Table 2. Most study participants reported English as their preferred language (84%). Of participants who reported cultural identity (82%), the most prevalent cultural identities were Indigenous (19%) and Canadian (19%); 32% reported multiple identities.

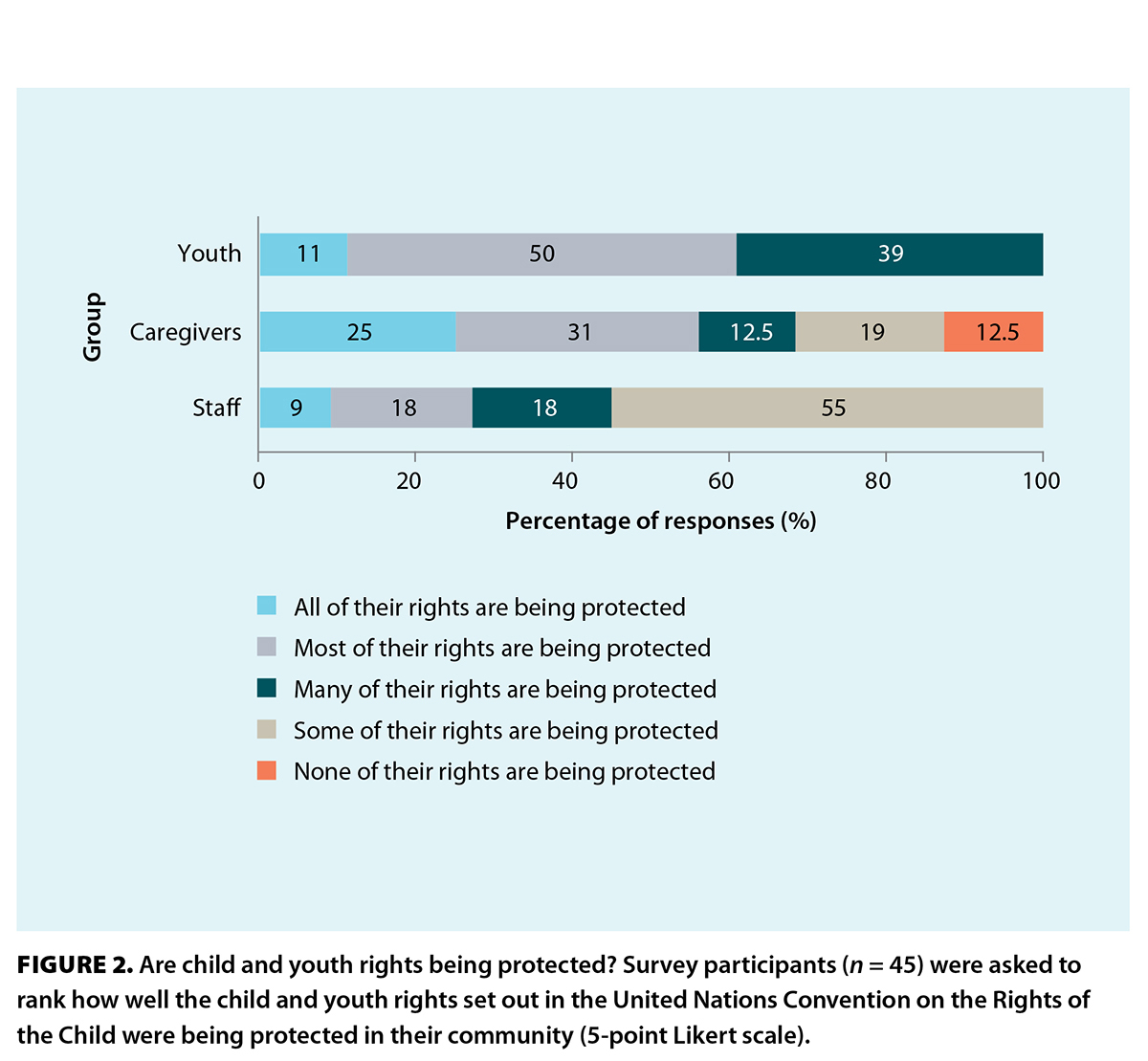

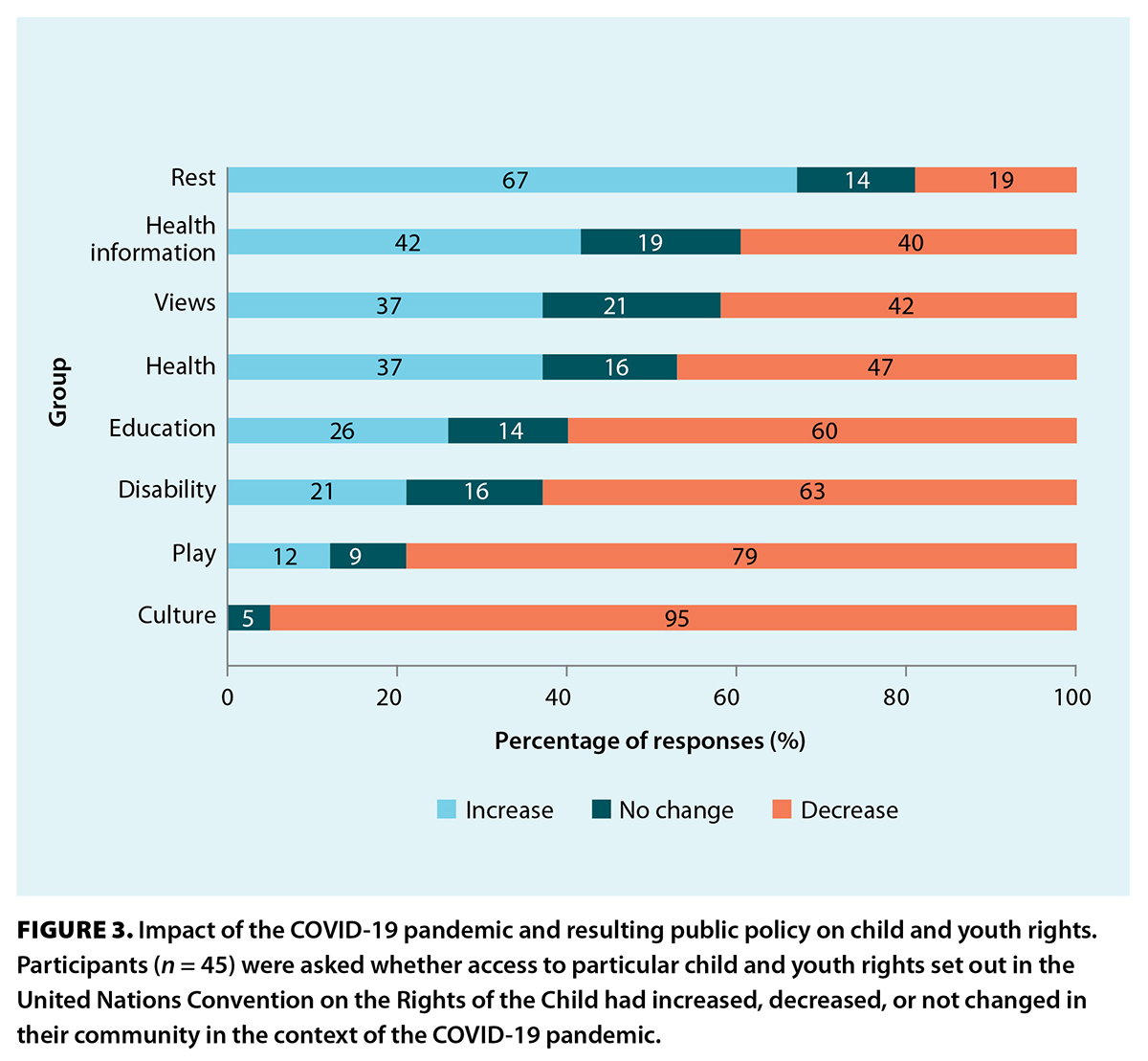

Overall, 72% of youth reported they did not know the UNCRC existed prior to participating in our survey. All participants reported that children and youth of all ages had the most access to rest, play, and culture, and the least access to respect for their opinions and views. Disappointingly, only about half the participants believed that most or all rights outlined in the UNCRC were protected in their community, and almost all reported that the COVID-19 pandemic impacted children and youth’s access to those rights. Most reported increased access to one right—rest—during the pandemic, versus decreased access to play, culture, disability, access to education, and aims of education [Figure 2 and Figure 3].

|

|

Engaging the voices of children and youth was challenging due to the perception from the academic community that they were too vulnerable to participate or provide informed consent. While protecting children and ensuring age-appropriate engagement is of utmost importance, barriers to engaging young children in a discussion of their rights can disempower this vulnerable group further and violate children’s right to have a voice.

Knowledge is power

Knowledge of rights among children and youth has been linked to better self-advocacy and social well-being.[7-9] A 2017 study asked over 54 000 children in 16 countries about their knowledge of their rights and found that 64% of them did not know about the UNCRC, and only 52% thought adults respected their rights.[8] Knowledge of the UNCRC among youth in our community was lower than in the 2017 study, which is concerning, but not surprising. Education about children’s rights is often sporadic or absent, particularly for children experiencing vulnerabilities.[8,10] Clearly identifying knowledge gaps among children and youth with respect to their rights emphasizes the importance of research and education initiatives that engage the voices of children to help communities realize their rights.[2,8,11]

We must continue to engage equity-deserving youth and communities in dialogue about child and youth intersecting rights to bolster education, advocacy, and well-being.

To mobilize learning from our survey results into meaningful action, the survey and research methods developed in this project will be used to foster ongoing dialogue about access to child and youth rights in the DTES and associated inner-city communities and with additional populations, including children and youth with complex health and developmental conditions at BC Children’s Hospital.

We call on readers to engage in dialogue about the UNCRC in their communities to help children fully develop their personalities; assume community responsibilities; and live with equality, dignity, and peace. This could include familiarizing yourself with the UNCRC articles, hanging posters featuring the UNCRC in your office or clinic to educate others, and role-modeling respect for children’s rights.

Many BC organizations provide resources and opportunities to engage further with human rights. British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner has created book club facilitation guides for adult and preschool-aged books and several awareness campaigns for community members.[12,13] The Office of the Representative for Children and Youth has a number of reports, statements, and recommendations that may be incorporated into professional development programs.[14] The Society for Children and Youth of BC has examples of child- and youth-friendly community programs, including walking school buses, where community members volunteer to walk groups of students to school along a predetermined route, contributing to UNCRC articles 24 and 29.[15] In conclusion, we ask you to consider how you would rate your level of familiarity with child and youth rights.

Acknowledgments

The survey was co-created and implemented on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territories of the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh, and Squamish Nations. The authors appreciate the time and willingness of all study participants, particularly the children and youth. The authors also thank the RayCam Co-operative Centre community, the Responsive Intersectoral Child and Community Health Education and Research team (www.bcchr.ca/RICHER), the University of British Columbia Community-University Engagement Support fund (https://communityengagement.ubc.ca/our-work/cues-fund/), and Mr Damian Duffy from BC Children’s Hospital’s Office of Pediatric Surgical Evaluation and Innovation (www.bcchr.ca/opsei/surgery-and-society) for making this project possible.

Competing interests

None declared.

Funding

The study received $30 000 in funding from the 2019–2020 UBC Community-University Engagement Support fund.

hidden

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. 20 November 1989. Accessed 24 February 2025. www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child.

2. Queen’s University Belfast Centre for Children’s Rights, GlobalChild. The global child rights dialogue (GCRD) final report. 2019. Accessed 24 February 2025. www.unb.ca/globalchild/_assets/documents/gcrd-full-report-final.pdf.

3. Goldhagen J, Clarke A, Dixon P, et al. Thirtieth anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child: Advancing a child rights-based approach to child health and well-being. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000589. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2019-000589.

4. Noël, J-F. The Convention on the Rights of the Child. Department of Justice Canada. Modified 21 December 2022. Accessed 1 November 2024. www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/divorce/crc-crde/conv2a.html.

5. Faulkner EA, Nyamutata C. The decolonisation of children’s rights and the colonial contours of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Int J Child Rights 2020;28:66-88. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02801009.

6. UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, UNICEF Canada. Not there yet: Canada’s implementation of the general measures of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. 2009. Accessed 24 February 2025. https://rightsofchildren.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Not-There-Yet-Canadas-implementation-of-the-general-measures-for-childrens-rights.pdf.

7. Peterson-Badali M, Ruck MD. Studying children’s perspectives on self-determination and nurturance rights: Issues and challenges. J Soc Issues 2008;64:749-769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00587.x.

8. Kosher H, Ben-Arieh A. What children think about their rights and their well-being: A cross-national comparison. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2017;87:256-273.

9. Tenenbaum HR, Ingoglia S, Wiium N, et al. Can we increase children’s rights endorsement and knowledge?: A pilot study based on the reference framework of competences for democratic culture. Eur J Dev Psychol 2023;20:1042-1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2022.2095367.

10. Horner-Johnson W, Bailey D. Assessing understanding and obtaining consent from adults with intellectual disabilities for a health promotion study. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 2013;10:260-265. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12048.

11. Raman S, Harries M, Nathawad R, et al. Where do we go from here? A child rights-based response to COVID-19. BMJ Paediatr Open 2020;4:e000714. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000714.

12. British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. Commissioner’s book club. Accessed 24 February 2025. https://bchumanrights.ca/resources/commissioners-book-club/.

13. British Columbia’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner. Awareness campaigns. Accessed 24 February 2025. https://bchumanrights.ca/resources/awareness-campaigns/.

14. Office of the Representative for Children and Youth. Reports and publications. Accessed 24 February 2025. https://rcybc.ca/reports-and-publications/reports/.

15. Society for Children and Youth of BC. Child and youth friendly communities program. Accessed 24 February 2025. https://scyofbc.org/child-and-youth-friendly-communities/.

hidden

Dr Binda is a resident physician in the Division of General Surgery in the Department of Surgery at the University of Ottawa. Dr Beevor-Potts is a resident physician in the Urology Residency Program at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine University. Ms McFadden is a PhD candidate and assistant professor at the University of British Columbia School of Nursing. Ms Prince Lea was the director of community programs at the RayCam Co-operative Centre at the time of writing. Ms Bland is a nurse practitioner at BC Children’s Hospital. Dr Lau is a program coordinator at BC Children’s Hospital. Ms Hodgson is a coordinator at the RayCam Co-operative Centre. Dr Vaghri is an associate professor in the Faculty of Business at the University of New Brunswick. Dr Loock is an associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine at UBC.

Corresponding author: Dr Catherine Binda, catbinda@student.ubc.ca.