Failing health care delivery in Canada is the result of an outdated operating model

A comparison of the performance of Canada’s publicly funded health care model with that of the Netherlands shows that the Netherlands provides double the benefits for approximately the same costs per capita. A root-cause failure analysis was conducted to determine the cause of the discrepancy.

Canada’s publicly funded health care system is failing. No credible cause has been found, which is crucial to finding a workable solution. In the search for answers to the proximal causes of too few physicians, nurses, hospital beds, and diagnostic and treatment facilities, a root-cause failure analysis was used to compare Canada with a country that has a perennially high-performing system.[1] From four advanced countries with leading publicly funded health care rankings—Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands—the Netherlands was chosen because its per-capita annual health care expenditure most closely resembles Canada’s.[2-4]

Canada and the Netherlands are affluent countries with advanced market economies and a strong social orientation, often referred to as welfare capitalism.[5] Canada is approximately 240 times the size of the Netherlands, with a population of 41.5 million.[2-4] The population of the Netherlands is 18.3 million. In 2024, Canada’s per-capita GDP was $67 853 (all dollar values are in Canadian dollars unless otherwise specified). The Netherlands’ was 39% higher, at $94 500.[6] Personal income taxes in the two countries are similar, but the Netherlands has a value-added sales tax of 21% as well as a wealth tax, reducing median disposable household income in 2021 to $45 000, $3750 less than in Canada, which has no wealth tax and combined federal and provincial sales taxes up to 15%.[6,7] Both countries have had publicly funded health care for more than 60 years. Although there are similarities, they differ fundamentally in how they are funded and who operates the programs. For both, the central (federal) parliament decides the benefits package and is responsible for enforcing the standards of care. The proportions of the population that are 65 years and older and 80 years and older are similar in the two countries.[8,9]

In Canada, the Medical Care Act[10] of 1966 introduced publicly funded health care, based on Britain’s model of financing through taxation combined with public ownership of hospitals and operation by government.[10,11] Unlike Britain, which uses salaries to pay its physicians, Canada continued to use fee-for-service remuneration.[10,12] It also differs from both Britain and the Netherlands in that it uses a separate program for each province and territory, rather than a single program for the entire country.[10,12]

In the Netherlands, publicly funded health care was introduced during the Second World War, based on the German model.[13] Although the country is made up of 12 provinces, it has one national health insurance plan, with a uniform benefits package delivered by the private insurance sector using a not-for-profit public contract model.[11,13] Health insurance is compulsory for all permanent residents. Insurers must take all applicants regardless of health status and guarantee finding a family physician if necessary. Patients are free to choose their insurer, primary care practitioner, and hospital. Premiums are the same for all insurers and are set by the central government in consultation with the insurance companies. Insurers compete on premiums, service, quality of care offered, and profits from supplementary insurance. Premiums are collected monthly using the pay system or private billing. There are no user charges. The federal government pays the premiums for children and adolescents up to the age of 18 and subsidizes the premiums for low-income citizens. The collected premiums are deposited in sickness funds controlled by not-for-profit nongovernment public agencies.[13] Insurers contract with the family physician section and the various consulting specialists’ sections and hospitals, or they may provide care directly using their own facilities and staff. Family physician billings, referred to as “functions of care,” are standardized among insurers and are paid from the sickness funds, as are the hospitals and consulting specialists.[13]

Developments that led to the need for changes

In the last quarter of the 20th century, the publicly funded health care systems in both Canada and the Netherlands began to experience inadequate access to health care and rising costs that threatened sustainability. In response, the two countries took very different approaches to attempt to make corrections. Canada’s system had initially been successful and popular with the public; however, it soon outspent its allocated funding, which the federal government responded to by introducing Established Programs Financing in 1977, reducing federal funding of provinces’ and territories’ health care costs from 50% to 24%.[14] The provincial and territorial governments responded by decreasing their fee-for-service annual increases to half the rate of general inflation.[15] Extra billing was permitted, but when it increased from $2 million to $200 million between 1979 and 1983, the federal government responded with the Canada Health Act of 1984.[10] It reaffirmed the four original principles of the Medical Care Act (public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, and portability); slightly modified the first principle to “administration on a nonprofit basis by a public authority”; and added a fifth principle, “must provide . . . reasonable access to those services.” Extra billing was not made illegal, but provinces and territories were deducted an amount equal to the extra amount billed, effectively stopping it. To further reduce expenditures on health care, Canada reduced its homegrown supply of physicians in the 1990s by decreasing medical school admission numbers, based on the correlation between the size of the physician work force and health care expenditures.[16] It retained its 21 medical services plans, 13 operated by provincial or territorial governments and 8 operated directly by the federal government for various segments of the population, such as the Canadian Armed Forces, the RCMP, First Nations, and federal prisons. There is also a separate plan for federal members of parliament and their families.[12] The changes resulted in a gradual decrease in access to health care, combined with rising costs well beyond general inflation. The relationship between the medical profession and government became increasingly more problematic, and at times threatening to physicians.[17] Since then, there has been a marked decrease in the comprehensiveness of family practice and a high rate of family physicians leaving it.[18]

The Netherlands experienced a gradual deterioration in the provision of health care services and unsustainable rising costs starting in the 1970s.[13] By the end of the last century, “the universal health care system was failing, operating under top-down cost-containment policies, such as regulation of doctors’ fees and hospital budgets, that were widely criticized for lacking incentives for efficiency and innovation.”[19] After several years of study, this led to the Health Insurance Act of 2006, which, on the advice of Stanford economist Alain Enthoven, shied away from the command-and-control top-down approach adopted in Canada. Instead, it focused on introducing market forces of “incentives for efficiency and innovations.”[19] Key to improving efficiency was to make family physicians the gatekeepers of health care costs by making them the only mechanism for patients to enter the system, except in true emergencies such as automobile accidents. A frugal approach to referring patients to consulting specialist care was incentivized by making the family physician section’s total remuneration inversely proportional to its use of specialty care. The cooperation of patients was cultivated by splitting the health insurance premium into two components, the basic benefits package and the deductible (eigen risico, or “own risk”).[20] The basic benefits package covers primary and hospital care, while the deductible, at slightly more than €1 per day, is used for the first €385 of consulting specialist care in a year, after which the basic benefits package pays for any continuing need for specialty care. The disincentive effect on patients has also recently begun to be used for patients requesting blood tests that are considered unnecessary by a family physician. A further difference in the attempt to improve access and sustainability was the recognition by the Netherlands’ planners of the need for a culture based on a common vision that acknowledges the central role of physicians in health care, including the efficient use of resources.[19] It recognizes the importance of adequately remunerated time opportunity and the necessary means to motivate high performance by physicians.[21] In that respect, the Netherlands started with two advantages over Canada: a lower cost to become a physician and an equal relationship with the operators of the public contract health care system, as opposed to the top-down command-and-control system in Canada, along with its adversarial relationship.

Performance comparison between the current health care systems of Canada and the Netherlands

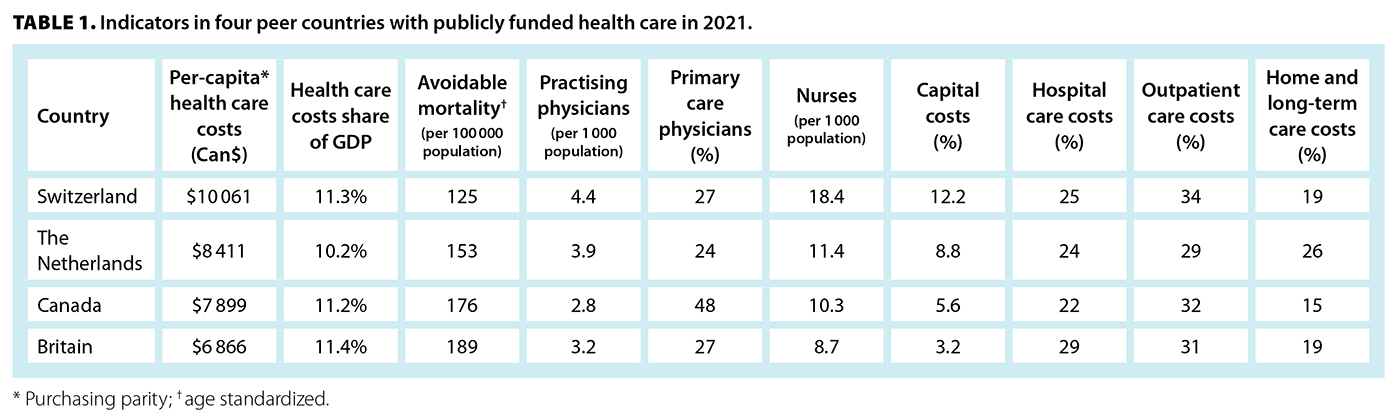

An evaluation of the performance of the publicly funded health care systems of Canada and the Netherlands, after changes to improve access and ensure sustainability, must take into account that the Netherlands is a much smaller country, with the population residing within 15 minutes of their family physician’s practice by car, and no more than half an hour from a hospital and consulting specialist care. The ubiquitous, highly integrated public transport system is also a major advantage for both patients and medical school students, all of whom live within 1 hour of a medical school via public transportation, on which they can travel for free on a student pass. In addition, financial support is readily available for those who need it. These fortuitous conditions were made possible by the discovery of a large natural gas field in the north of the country in 1959, which is now closed.[22] The multiparty elected politicians of the day agreed to use the proceeds to build a capitalist welfare state, focusing on education and training for the future workforce for a planned, modern, technologically sophisticated economy. The Netherlands recognized the importance of the social determinants of health, ensuring adequate future opportunities and support for people with lower incomes, including generous pensions. The long-term effect is that the Netherlands has one of the highest median household incomes in Europe, largely due to its secondary manufacturing and service industries. Its use of a substantial one-time natural resource for the benefit of the country created great social solidarity, including for its publicly funded health care system and its caregivers.[23] Table 1 shows expenditures on the various components of publicly funded health care, published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[2] Included are Switzerland, as the best-performing country, and Britain, as the only other developed country with health care services delivered by the government.

Per-capita expenditure in the Netherlands was 6% more than in Canada and 23% more than in Britain, but 20% less than in Switzerland. Britain spent 15% less than Canada. For overall performance, the Netherlands placed second out of the top 10 leading performers, while Canada ranked 10th, just ahead of Britain.[2] The relatively low hospital expenditures in the Netherlands are the result of its extensive long-term care and home-care programs [Table 1]. At 26%, it spends nearly double Canada’s 15% on long-term care, which allows people to stay in their homes longer, saving expensive hospital care. According to the 2021 World Index of Healthcare Innovation, whose rankings correlate closely with overall performance,[24] Canada ranked 23rd, while the Netherlands ranked second.

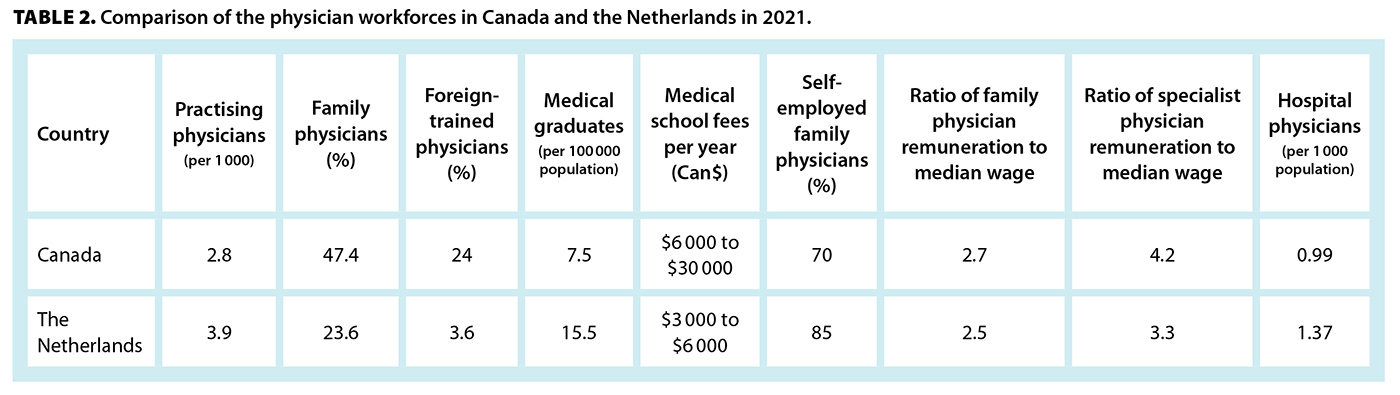

The physician workforce is a major determinant of the performance of health care systems. Table 2 shows how they compare in Canada and the Netherlands following changes that were made to improve access and sustainability. There are many more physicians in the Netherlands, and nearly all are homegrown, having benefited from a shorter and less personally expensive medical school education. Of the 39% more practising physicians, only 23.6% are family physicians, compared with 47.4% in Canada. Nevertheless, family physicians are the dominant physician factor in the delivery of health care services in the Netherlands in their role as gatekeepers to maintain sustainability. The supply of physicians is provided almost entirely by graduates from the Netherlands, at more than double the annual rate of Canada.[8,9] Foreign-trained physicians, at 3.6%, are one-seventh of those in Canada. Qualification for medical school is simpler, with no requirement for a premedical university education to qualify for the 6-year medical school curriculum. Fees are significantly lower than in Canada, ranging from $3000 to $6000 per year. Specialization for family medicine and the many secondary and tertiary specialties are similar in the two countries. Physician incomes, expressed as ratios to median income, are quite similar for family physicians. However, the incomes of Canadian consulting specialists exceed those of their family physician colleagues by 55%, more than their Dutch consulting specialist peers, who have 30% higher incomes.[8,9]

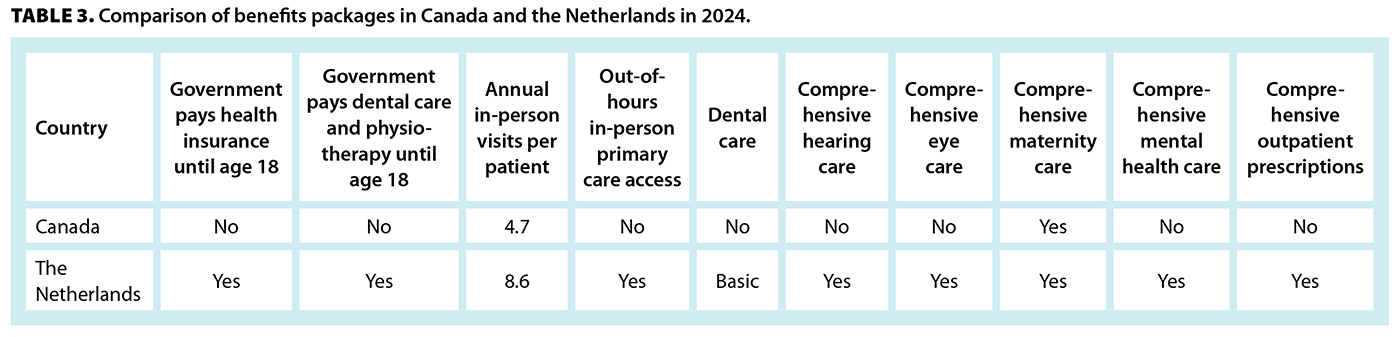

The average number of annual in-person doctor consultations is 4.7 in Canada and nearly double that in the Netherlands, at 8.6. The benefits package in Canada is for “medically necessary services” provided by physicians and hospitals. It is not universally comprehensive, excluding prescription medications and comprehensive eye, hearing, dental, and psychological care [Table 3].[8,12] In the Netherlands, these are included, with full dental care and physiotherapy for children and adolescents up to age 18, and health insurance premiums are paid by the federal government until age 18.[9,13] For young adults pursuing higher education, there are special health subsidies to pay for compulsory health insurance during their education, depending on the individual’s income. Table 3 demonstrates some of the differences in the benefits packages.

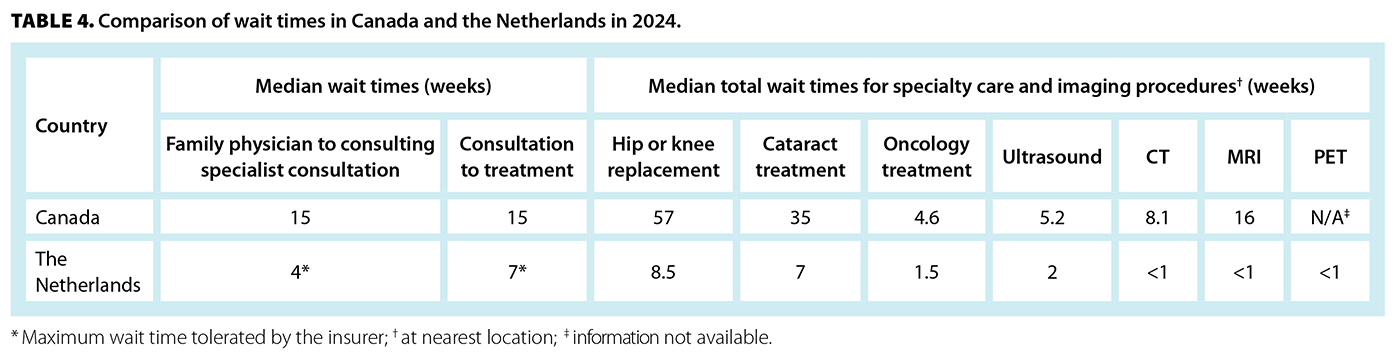

The promptness with which benefits are delivered also varies. Unlike the difficulty in accessing primary care in Canada,[28] in the Netherlands, it is available immediately: 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 52 weeks a year for urgent care and same-day appointments if deemed necessary by the patient. It is facilitated by the relatively large capitation payment of the blended remuneration formula, freedom for a patient to switch family physicians anytime, and ready availability of family physicians taking new patients. It also makes it attractive for family physicians to locate their practice where there is a need. Access to specialty care is via the family physician and is immediate if needed. Table 4 shows the wait times for specialty care. There are many places to have tests and investigations done, including hospitals. All payments are provided by the patient’s insurer.[13]

Delivery of primary care

In Canada, primary care is provided by family physicians operating private practices and nurse practitioners salaried by governments.[6,7] Physicians are remunerated in various forms, mostly fee-for-service, but often with some form of rostering payment and/or subsidies. Most provincial and territorial payment modalities do not support multidisciplinary teams. Except in rural areas, 24/7 in-person primary care coverage is minimal or nonexistent and has become expected to be made available by government-operated hospital emergency departments, as in Britain.[29] Hospitalists for inpatient care are recruited from the family physician pool.

Primary medical care in the Netherlands plays a dominant role in both providing health care and containing costs. It is provided by family physicians who own and operate primary care practices composed of multidisciplinary teams of nurses, “practice supporters” (physician assistants with specialty-training enhancement in various system disorders, designated by a specialty-specific notation, -sp), dietitians, midwives, and psychologists. Family physician practices average 5.4 practice supporters, of which 1.8 are specialized in mental health.[8,9] The family physician owner–operator of the practice is the most responsible physician for all patients attending the practice, is responsible for all billings, and pays all expenses, including salaries. Remuneration consists of a blend of mostly annual capitation payments to encourage large panels of patients, with modest visit and special disorders fees. Family physician–owners may employ other physicians to assume the most-responsible-physician function in their absence. Patients are automatically registered on their first visit and may change family physicians at any time. Access to medical care is via family physicians only, except in emergencies such as motor vehicle accidents, making family physicians the gatekeepers of the health care system by controlling access to more expensive specialty care.[9,13] Appointments with family physicians average 15 minutes each and are limited to one disorder per visit. For special circumstances, an appointment may be booked for two disorders, doubling the appointment duration. Family physicians are required to provide comprehensive primary medical care, including 24/7/365 after-hours coverage through participation on a rotational basis providing in-person care from a regional primary care centre.[13] Patients requiring urgent primary care outside office hours must call the general emergency phone number to be directed to the centre. The average number of capitated patients per family physician is slightly more than 2200.[13] Obstetric care is initiated via a midwife or family physician, working closely with a consulting specialist obstetrician/gynecologist and a hospital. Family physicians no longer provide hospital care but refer patients to consulting specialists at the hospital of their or their patient’s choice.

Delivery of specialty care

Specialty care is similarly provided in Canada and the Netherlands, but there are some important differences. Except in rural areas in the Netherlands, family physicians no longer provide hospital care but refer their patients to their consulting specialist or hospital of choice. In both countries, remuneration may be with section-specific negotiated fees-for-service, but in the Netherlands, consulting specialists may be employed by a hospital and receive a salary.[13] Unlike in Canada, where hospitals are owned and operated by the provincial and territorial governments using global budgeting, in the Netherlands, they are owned and operated by not-for-profit organizations, commonly the local municipality.[13] For inpatient services, hospitals and physicians are paid using diagnostic treatment combinations. Hospitals and insurers are allowed to negotiate prices freely and contract selectively for approximately 7000 of the 35 000 diagnostic treatment combinations.[9,13]

Inpatient facilities and their operation differ considerably between the two countries.[8,9] Canada has 2.6 hospital beds per 1000 population, while the Netherlands has 3. Average length of stay in hospital is 7.8 days in Canada but 5.2 days in the Netherlands. The hospital physician workforce per 1000 population consists of 0.99 physicians in Canada, but 1.37 in the Netherlands. Hospitalists recruited from family physicians are widely employed in Canadian hospitals to provide inpatient care. In the Netherlands, inpatient care is provided by medical graduates training to become consulting specialists under the supervision of trained consulting specialists. Inpatient 24-hour hospital coverage is the responsibility of each specialty section. Unlike in Canada, the use of CT, MRI, and PET examinations in the Netherlands is reserved for consulting specialists. There is little difference in the frequency of use of CT and MRI exams between the two countries, but PET exams are more common in the Netherlands. Medical insurance companies encourage competition among hospitals and groups of consulting specialists for common elective procedures, including surgeries. Table 4 shows the much shorter wait times for specialty consultations and procedures in the Netherlands, including for sophisticated imaging procedures.[9]

Conclusions

Canadians are concerned about the lack of timely access to primary and specialty care. In the Netherlands, physicians and patients alike are relatively content with their highly integrated universal health care system. From a global perspective, compared with peer countries with publicly funded health care, the Netherlands scores very high, much higher than Canada, while spending just 6% more per capita [Table 1]. Although Switzerland slightly outperforms the Netherlands, it does so by spending 20% more per capita. From the patient’s perspective, the benefits package in the Netherlands is markedly superior to that in Canada [Table 3], as are wait times for specialized care [Table 4]. The premise is that Canada’s system of publicly funded health care is failing because of its top-down command-and-control delivery model. The Netherlands’ public contract model, operated by insurance companies, outperforms Canada’s in every respect. The breadth of its superior performance suggests that the problem in Canada’s performance is the result of a pervasive defect negatively affecting the system in many ways, making piecemeal corrections in individual components ineffective for the system at large. Rather, there should be an examination of what has worked elsewhere. Most importantly, consideration should be given to whether the command-and-control delivery model of health care is likely to deliver quality care to the whole population in the most efficient manner. There are only two rich countries with modern economies, Canada and Britain, that continue to use it. Although Britain can claim inadequate expenditures, Canada spends as much as its highly successful peers. It is high time that the federal government reviewed its unanimous 1984 decision of adopting the currently operating version of publicly funded health care. At the time, it was not well known that the disastrous economies of the communist countries of Eastern Europe and China used that model to operate their economies.[5,30] Once those countries recognized the problems and introduced market forces, their economies began to flourish. Unfortunately, Canada and Britain continue to use the top-down command-and-control systems, reducing physicians to foot soldiers. It commands a too-small army to battle disease, distress, and disorders without sufficient time opportunity, adequate means, or a morale-building cooperative relationship.

When timely access to medical services began to fail and rising costs became unsustainable, Canada and the Netherlands reacted quite differently. Canada responded with a decrease in physician remuneration combined with maintaining a low physician-to-patient ratio and continued its top-down command-and-control government-operated model. The Netherlands responded with a culture of a common vision of quality and efficiency, using market mechanisms to promote entrepreneurship and competition. By actively engaging physicians to improve efficiency by responding to deficiencies and scarcities of essential needs, they have succeeded in changing the Netherlands’ health care system from its unsustainable state at the start of the century to a well-performing efficient system, producing superior benefits. Primary and specialty care functions are more clearly defined than in Canada, with the Netherlands being an effective gatekeeper. On a positive note, the sorry situation Canada finds itself in may be yet another opportunity for nation building by introducing one uniform comprehensive health care insurance model for all Canadians.

Competing interests

None declared.

hidden

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Thirsk R. The lessons of the Columbia disaster can be applied to my current field of health care. Globe and Mail. 1 February 2025. Accessed 2 April 2025. www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-lessons-of-the-columbia-disaster-can-be-applied-to-my-current/.

2. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2019. OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1787/4dd50c09-en.

3. World Bank Group. GNI per capita, atlas method (current US$) – Canada. Accessed 6 June 2025. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GNP.PCAP.CD?locations=CA.

4. WorldData.info. Country comparison: Canada / Netherlands. Accessed 3 June 2025. www.worlddata.info/country-comparison.php?country1=CAN&country2=NLD.

5. Parkin M, Bade R. Economics: Canada in the global environment. Don Mills, ON: Addison Wesley Longman Publishing Co.; 1991.

6. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Income and wealth distribution databases. Accessed 12 August 2025. www.oecd.org/social/income-distribution-database.htm.

7. Omololu E. Sales tax in Canada 2025: Guide to GST, HST, PST and QST sales taxes. Updated 27 January 2025. Accessed 6 August 2025. www.savvynewcanadians.com/sales-tax-canada/.

8. World Health Systems Facts. Canada: Health system overview. Updated 28 July 2025. Accessed 6 August 2025. https://healthsystemsfacts.org/national-health-systems/national-health-insurance/canada/canada-health-system-overview/.

9. World Health Systems Facts. Netherlands: Health system overview. Updated 10 July 2025. Accessed 6 August 2025. https://healthsystemsfacts.org/national-health-systems/bismarck-model/netherlands/netherlands-health-system-overview/.

10. Canadian Museum of History. Making medicare: The history of health care in Canada, 1914–2007. YouTube. Accessed 6 August 2025. www.youtube.com/watch?v=mDbigrTb8bI.

11. Ham C. Health care reform: The difficulties of controlling spending at the macro level while promoting efficiency at the micro level. BMJ 1993;306:1223-1224. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.306.6887.1223.

12. Government of Canada. Health care system. Accessed 12 August 2025. www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-systems.html.

13. National Health Care Institute. The Dutch health care system. Accessed 8 August 2025. https://english.zorginstitutenederland.nl/about-us/healthcare-in-the-netherlands.

14. Brown MC. The implication of established program finance for national health insurance. Can Public Policy 1980;6:521-532. https://doi.org/10.2307/3550102.

15. Barer ML, Evans RG, McGrail KM, et al. Beneath the calm surface: The changing face of physician-service use in British Columbia, 1985/86 versus 1996/97. CMAJ 2004;170:803-807. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.1020460.

16. Barer ML, Stoddart GL. Toward integrated medical resource policies for Canada: 1. Background, process and perceived problems. CMAJ 1992;146:347-351.

17. Collier R. Doctors v. government: A history of conflict. CMAJ 2015;187:243. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-4986.

18. Chan BTB. The declining comprehensiveness of primary care. CMAJ 2002;166:429-434.

19. Enthoven AC, van de Ven WPMM. Going Dutch—Managed-competition health insurance in the Netherlands. N Engl J Med 2007;357:2421-2423. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp078199.

20. Leimer T. Dutch health insurance and healthcare in the Netherlands (2025). Feather. Accessed 8 August 2025. https://feather-insurance.com/en-nl/blog/health-insurance-netherlands-guide.

21. John A, Newton-Lewis T, Srinivasan S. Means, motives and opportunity: Determinants of community health worker performance. BMJ Glob Health 2019;4:e001790. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001790.

22. Groningen gas field. Wikipedia. Accessed 8 August 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Groningen_gas_field.

23. Eurostat. Living conditions in Europe – Income distribution and income inequality. Updated 24 November 2025. Accessed 10 July 2025. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Living_conditions_in_Europe_-_income_distribution_and_income_inequality.

24. Roy A, Girvan G. Key findings from the 2021 FREOPP World Index of Healthcare Innovation. The Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity. Accessed 9 August 2025. https://freopp.org/whitepapers/key-findings-from-the-2021-freopp-world-index-of-healthcare-innovation/.

25. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Wait times for priority procedures in Canada, 2025. Accessed 12 June 2025. www.cihi.ca/en/wait-times-for-priority-procedures-in-canada-2025.

26. Moir M, Barua B. Waiting your turn: Wait times for health care in Canada, 2023 report. Fraser Institute. 7 December 2023. Accessed 9 August 2025. www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/waiting-your-turn-wait-times-for-health-care-in-canada-2023.

27. World Population Review. Health care wait times by country 2025. Accessed 10 August 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/health-care-wait-times-by-country.

28. Lazenby A. BC doctors sound the alarm as drop-in medical clinics disappear. Times Colonist. 9 December 2024. Accessed 6 April 2025. www.timescolonist.com/local-news/bc-doctors-sound-the-alarm-as-drop-in-medical-clinics-disappear-9925957.

29. Hunt J. Zero. Eliminating unnecessary deaths in a post-pandemic NHS. London, UK: Swift Press; 2022.

30. Gregory PR, Stuart RC. Soviet economic structure and performance. New York: Harper and Row; 1981.

hidden

Dr Tevaarwerk is an endocrinologist, newly retired from clinical practice. He has worked as a physician on three continents and continues to be engaged with several joint Doctors of BC–Ministry of Health working groups focused on improving the efficiency of providing medical services.

Corresponding author: Dr Gerald Tevaarwerk, gerald.tevaarwerk@gmail.com.

Indeed, another Fraser Institute report aligns generally with your points about the superiority of the health system in the Netherlands:

"Comparing Performance of Universal Health Care Countries, 2024": https://www.fraserinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/comparing-pe...

In NL Times, some concerns emerge about health-related issue:

"Health insurance suddenly displaces asylum, housing as main theme in latest debate":

https://nltimes.nl/2025/10/21/health-insurance-suddenly-displaces-asylum...