Presentation of pediatric cannabis ingestion in the emergency department

ABSTRACT

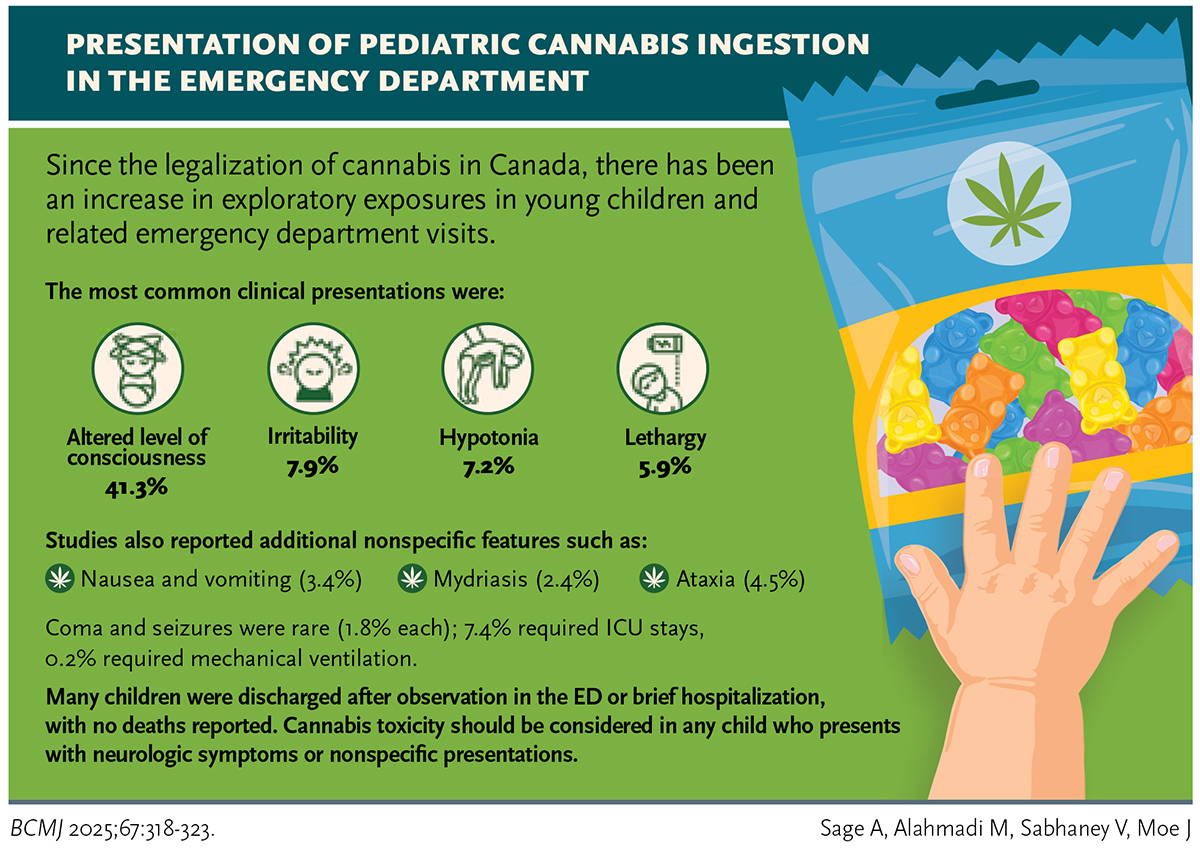

Background: Since the legalization of cannabis in Canada, there has been an increase in exploratory exposures in young children and related emergency department visits.

Methods: We synthesized published peer-reviewed studies on clinical presentations, management, and outcomes in children with unintentional exposure to cannabis. We reviewed the Medline and Embase databases for articles that discussed unintentional exposures to cannabis in children (≤ 18 years of age).

Results: We identified 429 articles, of which 46 met our inclusion criteria. Most patients (88.0%) ingested edible cannabis products, which included gummies, candies, chocolates, or baked products. The most common presentations included altered level of consciousness (41.3%), irritability (7.9%), hypotonia (7.2%), and lethargy (5.9%); however, additional nonspecific features such as nausea and vomiting (3.3%), mydriasis (2.4%), and ataxia (4.5%) were also reported. Serious presentations such as coma and seizure were infrequently reported (1.8% each), and some patients required mechanical ventilation (0.2%) or ICU stays (7.4%). Many children were ultimately discharged after observation in the emergency department or following brief hospitalization, and no deaths were reported. Urine toxicology screen was the most common method of confirming unintentional cannabis exposure (61.1%).

Conclusions: Cannabis toxicity should be considered in any child who presents with neurologic symptoms or nonspecific presentations. Prompt recognition may limit unnecessary extensive or invasive testing.

Cannabis toxicity should be considered in any child who presents with altered mental status, irritability, or ataxia, as well as nonspecific presentations.

Background

Background

The Cannabis Act, introduced for the purpose of deterring illicit activities and reducing the burden on the criminal justice system and the associated marginalization of specific groups, came into effect in Canada in October 2018 in a two-phase process.[1] One year after initial legalization of cannabis, access to cannabis products was extended from dried flowers, seeds, and oils to include edible cannabis products such as gummies and chocolates.[2]

Since the introduction of the Cannabis Act, there has been an increase in presentations to care—both ED visits and hospitalizations—due to unintentional cannabis exposure among children.[3,4] In Ontario, an increase from 0.8 to 9.6 cannabis-poisoning-related ED visits per 100 000 ED visits occurred between 2015 and 2019; a further increase to 18.1 cannabis-poisoning-related ED visits per 100 000 ED visits occurred in 2021, corresponding to a higher proportion of presentations related to the legalization and ingestion of edible cannabis products.[3] The higher burden of unintentional cannabis exposure since legalization is due in part to exploratory ingestions by children of often sweet-tasting and attractive-looking edible products.[5]

The psychoactive component of cannabis—tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)—is primarily responsible for CNS toxicity in pediatric exposures. THC is a lipophilic molecule that exerts its effects differently in children than in adults. Due to decreased adiposity and more localized arrangement of specific cannabinoid receptors in the brainstem, children experience more potent CNS effects compared with adults.[6,7] Further, because the onset of symptoms is often delayed up to 2 hours from the time of ingestion of edible cannabis products, children can continue to consume those products, leading to accumulation of high and very dangerous amounts of THC in the bloodstream.[8,9] Children with exposure to THC often present to care with nonspecific CNS symptoms, including altered level of consciousness, gait abnormalities, and seizures, as well as vital sign changes of tachycardia or respiratory depression.[10]

These features make unintentional cannabis exposure difficult to diagnose and subsequently to manage, which often results in increased hospital length of stay for observation.[11] Due to the increasing incidence of unintentional cannabis exposure, clinicians must be comfortable recognizing and treating cannabis intoxication in children. We reviewed the current published literature on unintentional exposure to cannabis in children and youth with the aim of providing a clinical resource for health care providers. To that end, we describe presenting signs and symptoms, management, and outcomes in pediatric patients with unintentional cannabis exposure.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included published peer-reviewed studies of children (≤ 18 years of age) with confirmed unintentional ingestion of cannabis. We required studies to describe the route of cannabis exposure, clinical signs and symptoms, investigations and medical interventions performed, and/or outcomes and disposition. We excluded narrative reviews and articles written in a language other than English.

Information sources and search strategy

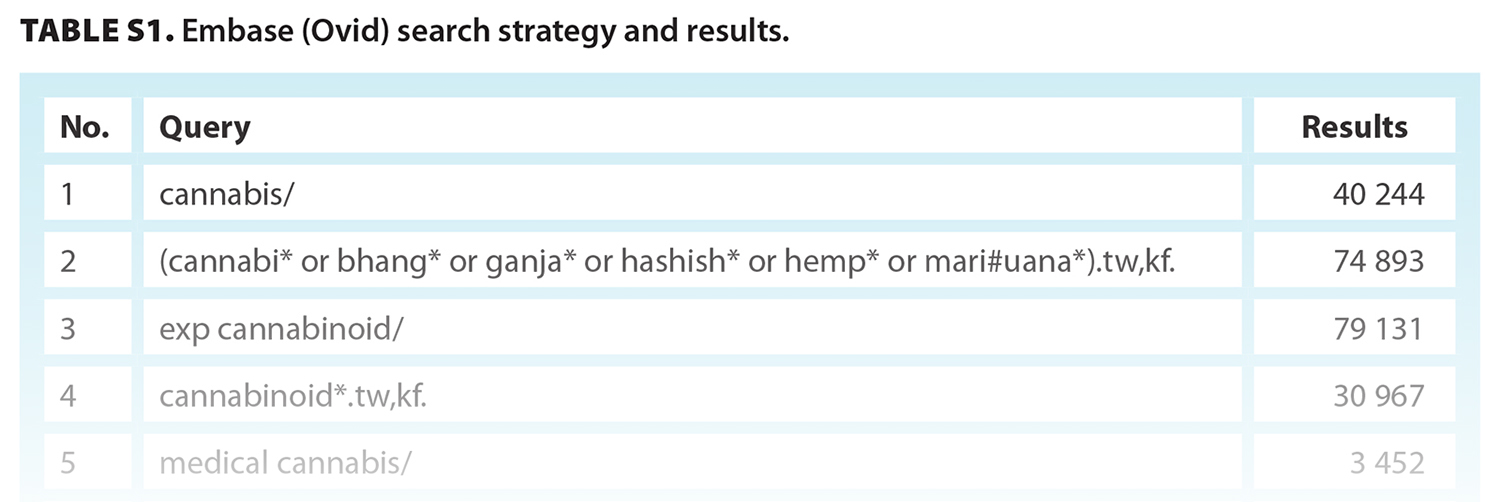

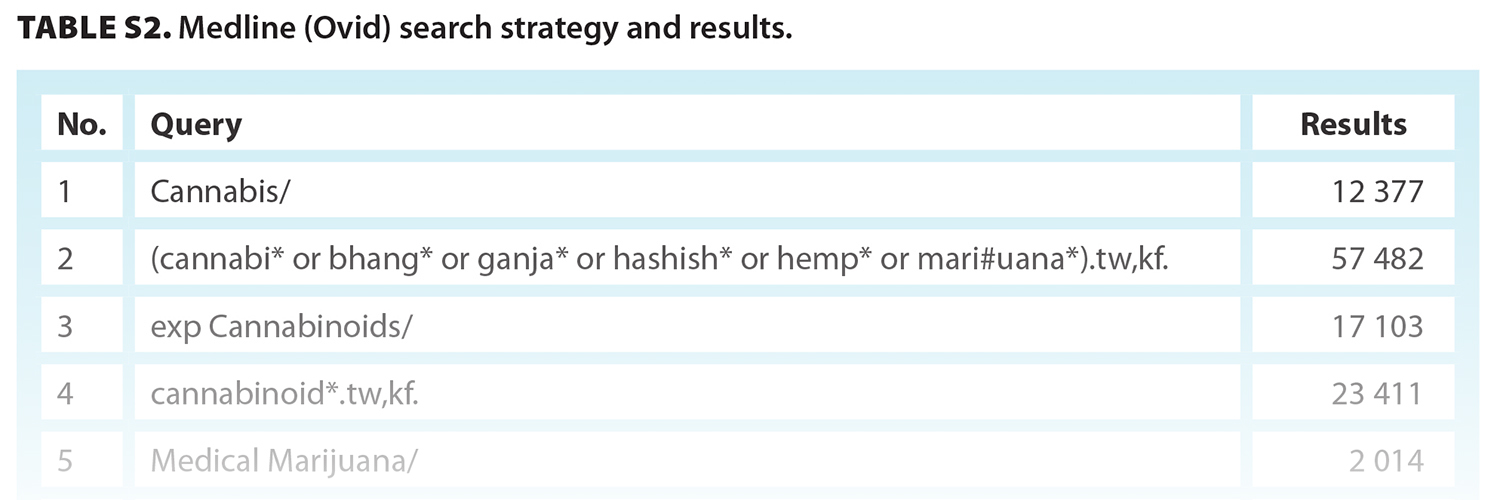

We reviewed published articles in both the Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (Medline; Ovid) and Embase (Ovid) databases, from their inception (Medline: 1946; Embase: 1974) to the date of our search (26 July 2022). We used Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), keywords, and author-assigned terms to identify articles that discussed unintentional cannabis ingestion in pediatric patients [Table S1, Table S2].

Study selection and data extraction

Study selection and data extraction

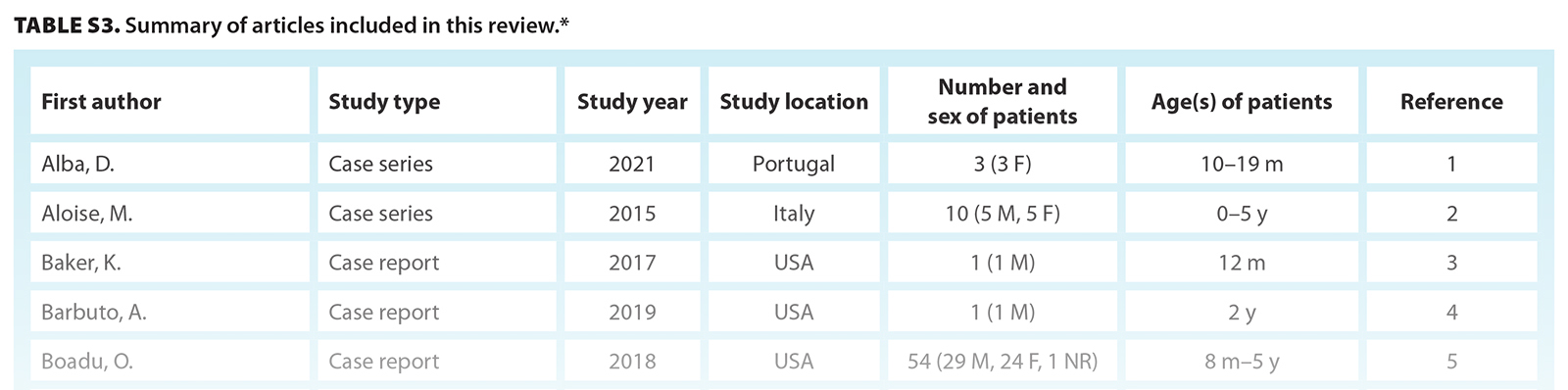

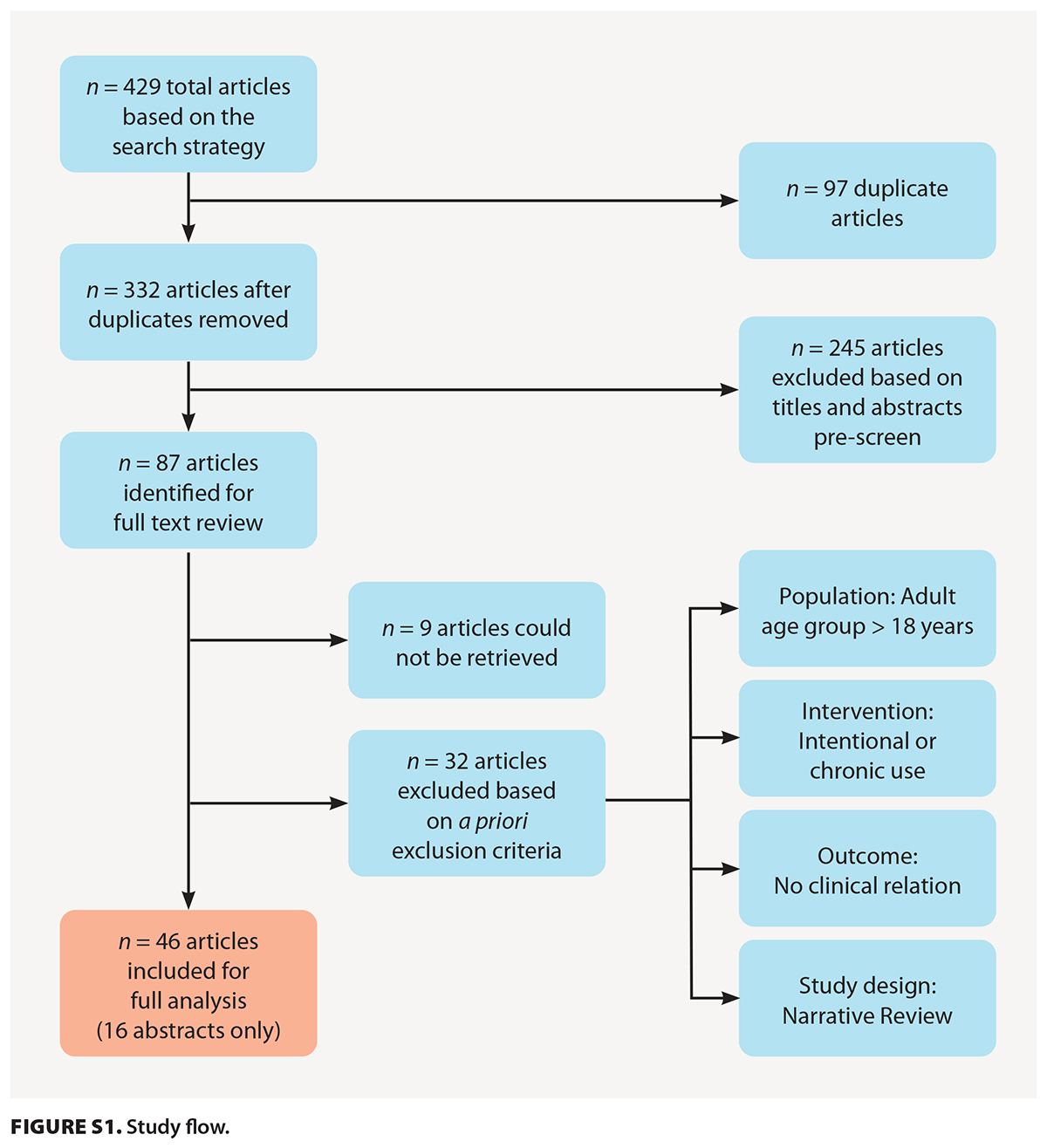

We first screened article titles to remove duplicates, those not written in English, and those that did not discuss the effects of cannabis ingestion in humans. We then obtained the articles we identified for review from the University of British Columbia Library. We removed articles that were not available in the library’s database; referred to an adult-only population or the intentional ingestion of cannabis; did not describe clinical presentation, treatment, or outcome; or were narrative reviews [Figure S1]. We then reviewed the full text of eligible articles and summarized it in relation to our study aim. Table S3 presents a summary of these articles.

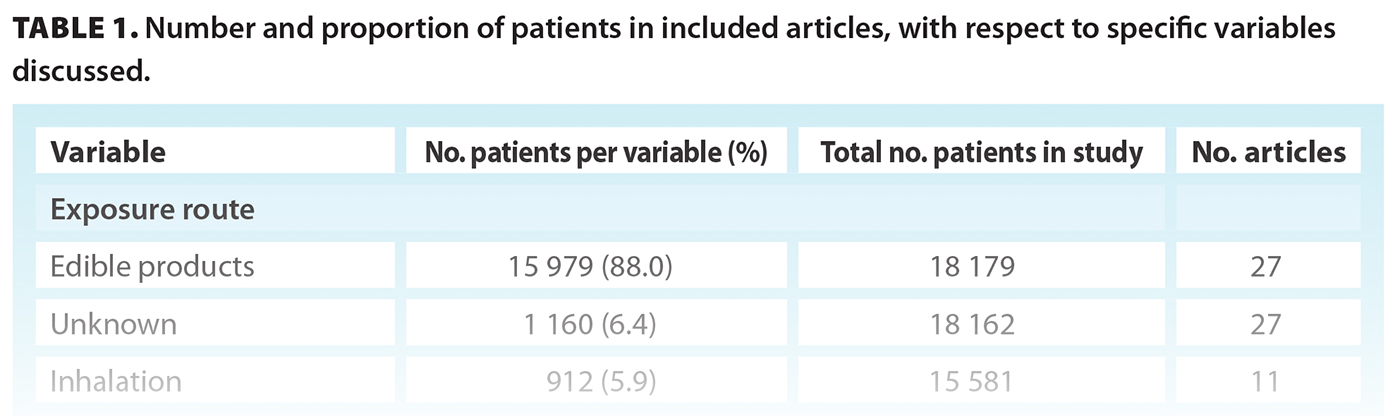

We present results as percentages of patients who were reported to be within a particular clinical category (e.g., symptom category) [Table 1].

Results

Search results and population demographics

Our search strategy yielded 429 articles. On initial review of titles and abstracts, we removed 97 duplicate articles and another 245 articles based on our exclusion criteria. We reviewed the full text of 87 articles and included 46 of them in our final review, 16 of which were abstracts in press [Figure S1, Table S3]. The included articles were published between 1983 and 2022, six prior to 2012. Most articles were published in the United States (n = 22), followed by Canada (n = 7) and France (n = 7); a small number were published in Italy (n = 3), Ireland (n = 2), Algeria (n = 1), Australia (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Scotland (n = 1), and the United Kingdom (n = 1). The studies included retrospective cohort studies (n = 17), case reports (n = 15), case series (n = 11), a systematic review (n = 1), an observational study (n = 1), and a prospective cohort study (n = 1) [Table S3]. The articles summarized clinical presentations, treatments, and/or outcomes for a total of 21 885 patients. Patients’ ages ranged from 2 months to 17 years; 44.9% were born female, 48.3% were born male, and 6.8% did not have their sex documented [Table S3].

Exposure

Note: The studies we referenced in each clinical category discussed are referred to by roman numeral in the following text.

Of the 46 studies reviewed, 35 (n = 18 192 patients)[i] included a description of the route of exposure [Table 1]. Most patients (88.0%) ingested edible cannabis products,[ii] which included gummies, candies, chocolates, or baked products. Only 5.9% of patients experienced unintentional inhalational exposure,[iii] and 6.4% had confirmed exposure via an unknown route.[iv]

Clinical presentation

Most articles described symptoms associated with cannabis exposure in children (40 articles, n = 20 724 patients)[v] [Table 1]. The most common clinical presentations involved CNS symptoms: altered mental status (41.3% of patients),[vi] followed by irritability (7.9%)[vii] and lethargy (5.9%).[viii] Presentations that required critical intervention were less frequently reported: coma (1.8%),[ix] seizure (1.8%),[x] and respiratory depression (1.7%).[xi] With respect to non-CNS-related presentations, the studies described mainly gastrointestinal symptoms, specifically nausea and vomiting (3.3%).[xii] The articles infrequently discussed other symptoms noted at initial presentation, including blurred vision, headache, and decreased appetite. We did not summarize the frequency of these symptoms because of the limited number of patients involved.

Physical examination findings

Physical examination findings were described less frequently (32 articles, n = 20 097 patients) [Table 1]. The most common findings on examination were hypotonia (7.2%),[xiii] conjunctival injection (4.9%),[xiv] and ataxia (4.5%).[xv] Mydriasis was also present in 2.4% of children exposed to cannabis.[xvi] Vital sign abnormalities included tachycardia (4.5%),[xvii] hypotension (1.2%),[xviii] and bradycardia (0.8%).[xix]

Investigations, management, and clinical outcomes

Overall, investigations were more often related to the clinical scenario than to cannabis ingestion. Many articles either described patients who did not receive investigations or focused on clinical trajectory with no discussion of investigations. Of the 46 studies reviewed, 34[xx] included some description of investigations. These studies included 4916 patients, 22.5% of the total 21 885 patients described in the articles included in this review.

Urine toxicology screen was the most common method of confirming unintentional cannabis exposure (61.1%)[xxi] [Table 1]. A smaller proportion of patients underwent serum drug screening (20.9%), although the specific substances tested were rarely discussed.[xxii] Basic laboratory analyses (complete blood count, electrolytes, liver panel, C-reactive protein, and/or blood cultures) were performed in 71.6% of patients.[xxiii] The use of diagnostic imaging was infrequently reported. Chest X-rays (36.0%),[xxiv] abdominal ultrasounds (14.7%),[xxv] and CT scans of the head (23.6%)[xxvi] were performed in some patients. Lumbar punctures were performed on 7.3% of patients.[xxvii] Ancillary investigations included ECG (26.8%)[xxviii] and EEG (10.5%).[xxix]

In the 38 articles that described disposition for patients with unintentional cannabis exposure (n = 18 445 patients),[xxx] most patients were monitored either in the ED (29.9%)[xxxi] or on the ward (43.5%).[xxxii] A smaller proportion of patients (7.4%)[xxxiii] required admission to the ICU, most often for intensive monitoring.

Management specific to THC was not typically required; when reported (32 articles; 20 625 patients),[xxxiv] it was largely supportive. Intravenous fluids were administered in 11.4% of patients,[xxxv] and supplemental oxygen was used in 1.9% of patients.[xxxvi] Gastric decontamination with activated charcoal was used in 1.9% of patients,[xxxvii] and two single-patient case reports published prior to legalization reported the use of gastric lavage.[xxxviii] Medications were very rarely used and were targeted to the clinical scenario; benzodiazepines were used in cases of seizure (1.2%).[xxxix] The benzodiazepine antagonist flumazenil was reported to treat a single case of altered level of consciousness with no clear exposure history.[xl] Finally, 0.2% of patients required mechanical ventilation[xli] because of poor respiratory effort or severely altered level of consciousness.

In all the articles reviewed, there were no cases of death resulting from unintentional cannabis ingestion. The articles focused on patients’ presentation and course in hospital; there was limited discussion of long-term follow-up and outcomes.

Discussion

Our review included 46 articles that described nearly 22 000 pediatric patients who presented to care in the setting of unintentional exposure to cannabis. These children were exposed to cannabis primarily through accidental ingestion of edible cannabis products. The most common presenting symptoms and signs associated with exposure were altered mental status, irritability, lethargy, and hypotonia. A small subset of patients had more serious presentations, with seizure, coma, or respiratory involvement. Most patients were discharged after observation, either in the ED or in hospital. A relatively small proportion of patients required admission to the ICU, which was often out of a need for intensive monitoring due to seizure or a substantially altered level of consciousness. Management of cannabis exposure was largely supportive, with intravenous fluids or supplemental oxygen. Many patients had exposure confirmed through urine toxicology screen. Further investigations were performed sparingly, in less than 5000 patients. Despite this, some patients underwent invasive investigations, such as lumbar puncture or exposure to ionizing radiation from neuroimaging. Reassuringly, no cases resulted in death.

Due to the widespread legalization of cannabis in Canada and other countries, it is important for clinicians to feel comfortable recognizing and managing accidental cannabis intoxication in the pediatric population. Most pediatric cannabis toxicity presentations are related to accidental ingestion of edible cannabis products. Unsurprisingly, the literature indicates a temporal association between the introduction of edible cannabis products in Canada and increased numbers of pediatric ED visits for cannabis exposure.[6] Thus, preventive strategies should be aimed at reducing the availability of these products to young children, as highlighted by the Canadian Paediatric Society. This includes implementing strict labeling standards and package warnings, especially in relation to visually attractive forms of edible cannabis like candies and chocolate; creating promotional limitations, especially with respect to social media; and restricting access to cannabis near locations frequented by children.[12]

An added challenge for physicians in managing unintentional cannabis exposure in children who present to the ED is the consideration of child maltreatment or neglect. Canadian data on rates of unintentional cannabis exposure are limited. Globally, the literature suggests there are high rates of referral to social services or child protection services for further assessment of neglect or maltreatment.[13] While some argue for widespread involvement of child protection services, others highlight the potential harm to families and exacerbation of sociocultural inequities inherent in current reporting structures. Recently, Raz and colleagues presented guidelines for practitioners on reporting to child protection services in cases of unintentional cannabis exposure, asking “1. Was this [truly] unintentional? 2. Did parents or guardians take steps to prevent ingestion, even if inadequate? 3. If the ingested substance was not THC, would this event be reportable? 4. What other factors contributed to this outcome?”[14] Taken together, the decision to report to child protection services should be based on the context of each case, in tandem with local reporting guidelines. For further guidance, the Government of British Columbia developed The B.C. Handbook for Action on Child Abuse and Neglect.[15]

Consistent with the pathophysiology of THC exposure in children, most patients presented with CNS findings. However, in our review, signs and symptoms of cannabis exposure were nonspecific; thus, it is important that clinicians maintain a high index of suspicion for cannabis exposure in children with nonspecific presentations. Urine toxicology can be used to confirm the diagnosis of THC exposure in children, because it has high sensitivity and specificity (both near 92%) for acute edible cannabis ingestions and a low proportion of false positives from secondhand cannabis smoke.[16,17] Given the varied presentations in unintentional cannabis ingestion, clinicians should inquire about access to substances when taking histories and consider including urine toxicology as part of the initial workup for children who present with altered mental status, irritability, and/or lethargy, particularly if there is an unknown or unclear history of ingestion. The investigations and therapies described in our review were largely case specific, indicating a lack of clear consensus in the literature. In cases of unintentional cannabis intoxication, the cornerstones of management are appropriate monitoring and supportive measures such as intravenous fluids and oxygen, as indicated.

Key findings and recommendations regarding cannabis exposure in children are summarized in the Box.

BOX. Unintentional cannabis exposure in children: Key findings and recommendations.

Clinical problem

- Increased access to and attractive marketing and formulations of cannabis products have resulted in increased unintentional cannabis exposure among children and associated visits to the ED.

- Symptoms and signs commonly associated with cannabis exposure are nonspecific.

- There is no exact dose–response relationship for cannabis, but oral bioavailability of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is higher in children than in adults.

Common presentation

- Symptoms: altered mental status, irritability, and lethargy.

- Signs: hypotonia, conjunctival injection, ataxia, and tachycardia.

Diagnosis and management

- In the absence of a clear exposure history, a high index of suspicion should be maintained in children with altered mentation. This may prompt recognition of cannabis exposure and limit excessive diagnostic testing.

- Urine toxicology is the method of choice for confirming cannabis exposure: it is sensitive, specific, and accessible.

- Blood investigations are nonspecific for cannabis exposure but may be helpful to exclude co-ingestions.

- Most children require supportive care and monitoring for respiratory compromise, seizure, or severe obtundation.

- Most children can be discharged after observation in the ED if they demonstrate improvement in symptoms; however, some may require admission to hospital.

Other considerations

- Consideration should be given to contacting child protection services on a case-by-case basis.

- Parents and guardians should be counseled on the safe handling and storage of cannabis.

- Legislation on access to and packaging of cannabis is required to prevent harms associated with exposure.

Study limitations

Our review was limited by the quality of the studies included, which retrospectively described clinical presentations, interventions, and short-term sequelae of unintentional cannabis exposure. Given their retrospective and short-term nature, most studies lacked comparisons to other causes of altered consciousness and did not describe long-term outcomes. To ensure a comprehensive review of the literature, we included case series, case reports, and abstracts in press. This introduced a potential bias toward the most symptomatic or severe presentations being included as case reports, which would overestimate the frequency of the symptoms and signs of unintentional cannabis exposure. Further, given the limited availability of published literature, our review included articles from worldwide populations, some of which may not be immediately generalizable to the specific context of Canadian EDs. A review of presentations of cannabis poisonings in the BC Children’s Hospital ED prior to legalization indicated that only 1.1% of poisonings treated at BC Children’s from 2016 to 2018 were related to unintentional cannabis exposure; this highlights the need for ongoing surveillance in BC EDs.[18]

Conclusions

Unintentional exposure to cannabis is an increasingly prevalent clinical entity. Due to the nonspecific nature of historical and physical examination findings of unintentional cannabis exposure in children, cannabis toxicity should be considered in any child who presents with neurologic symptoms such as altered mental status, irritability, or ataxia, as well as nonspecific presentations. Prompt recognition may limit unnecessary extensive or invasive testing. Despite the rarity of serious complications, including respiratory depression and seizures, future studies should seek to better identify risk factors for children to develop these complications. Beyond recognition of cannabis intoxication, clinicians and policymakers should address prevention through advocacy, counseling, and guideline-supported interventions to limit unintentional pediatric cannabis exposures to prevent harms.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We would especially like to thank Ms Edlyn Lim, MLIS, medical librarian, for her assistance in designing and conducting our database literature searches.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Cannabis Act, SC 2018, Chapter 16. Accessed 24 May 2025. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-24.5/.

2. Cannabis Regulations, SOR/2018-144. Accessed 24 May 2025. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2018-144/.

3. Varin M, Champagne A, Venugopal J, et al. Trends in cannabis-related emergency department visits and hospitalizations among children aged 0–11 years in Canada from 2015 to 2021: Spotlight on cannabis edibles. BMC Public Health 2023;23:2067. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16987-9.

4. Myran DT, Cantor N, Finkelstein Y, et al. Unintentional pediatric cannabis exposures after legalization of recreational cannabis in Canada. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5:e2142521. https://doi.org10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42521.

5. Myran DT, Tanuseputro P, Auger N, et al. Edible cannabis legalization and unintentional poisonings in children. N Engl J Med 2022;387:757-759. https://doi:10.1056/NEJMc2207661.

6. Chartier C, Penouil F, Blanc-Brisset I, et al. Pediatric cannabis poisonings in France: More and more frequent and severe. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2021;59:326-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2020.1806295.

7. Guidet C, Gregoire M, Le Dreau A, et al. Cannabis intoxication after accidental ingestion in infants: Urine and plasma concentrations of ∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), THC-COOH and 11-OH-THC in 10 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020;58:421-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1655569.

8. Helman A, Leblanc C, Bhate T, et al. Emergency medicine cases. EM quick hits #43: Pediatric cannabis poisoning, esophageal perforation, Brugada, career transitions in EM. October 2022. Accessed 24 May 2025. https://emergencymedicinecases.com/em-quick-hits-oct-2022/.

9. Whitehill JM, Dilley JA, Brooks-Russell A, et al. Edible cannabis exposures among children: 2017–2019. Pediatrics 2021;147:e2020019893. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-019893.

10. Blohm E, Sell P, Neavyn M. Cannabinoid toxicity in pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019;31:256-261. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0000000000000739.

11. Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: A systematic review. J Pediatr 2017;190:142-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.07.005.

12. Grant CN, Bélanger RE. Cannabis and Canada’s children and youth. Paediatr Child Health 2017;22:98-102. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx017.

13. Pélissier F, Claudet I, Pélissier-Alicot A-L, Franchitto N. Parental cannabis abuse and accidental intoxications in children: Prevention by detecting neglectful situations and at-risk families. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014;30:862-866. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000288.

14. Raz M, Gupta-Kagan J, Asnes AG. THC ingestions and child protective services: Guidelines for practitioners. J Addict Med 2025;19:350-352. https//doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000001441.

15. Government of British Columbia. The B.C. handbook for action on child abuse and neglect for service providers. 2017. Accessed 31 July 2025. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/public-safety-and-emergency-services/public-safety/protecting-children/childabusepreventionhandbook_serviceprovider.pdf.

16. Schlienz NJ, Cone EJ, Herrmann ES, et al. Pharmacokinetic characterization of 11-nor-9-carboxy- ∆9-tetrahydrocannabinol in urine following acute oral cannabis ingestion in healthy adults. J Anal Toxicol 2018;42:232-247. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/bkx102.

17. Van Oyen A, Barney N, Grabinski Z, et al. Urine toxicology test for children with altered mental status. Pediatrics 2023;152:e2022060861. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060861.

18. Cheng P, Zagaran A, Rajabali F, et al. Setting the baseline: A description of cannabis poisonings at a Canadian pediatric hospital prior to the legalization of recreational cannabis. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can 2020;40:193-200. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.40.5/6.08.

Table S3 references

1. Alba D, Paiva Ferreira I, Moreira M, et al. Accidental cannabinoid ingestion in children–A case series. Presented at the 13th Excellence in Pediatrics Conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2–4 December 2021. Abstract republished in: 2021 EIP abstract book. Cogent Med 2021;8:20. Abstract 189. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331205X.2021.2002558.

2. Aloise M, Giampreti A, Vecchio S, et al. Accidental hashish ingestion in children: A Pavia Poison Centre case series. Abstract republished in: XXXV International Congress of the European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) 26–29 May 2015, St Julian’s, Malta. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2015;53:291-292. Abstract 123.

3. Baker K, Hoyte C. Multiple seizures in a pediatric patient following marijuana ingestion. North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Abstracts. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2017;55:689-868. Abstract 203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1348043.

4. Barbuto A, Chiba, T, Burns M. Pediatric THC ingestion causing prolonged sedation and episodic hypoxia. North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Abstracts 2019. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2019;57:870-1052. Abstract 219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1636569.

5. Boadu OBA, Gombolay GY, Caviness VS, El Saleeby CM. Intoxication from accidental marijuana ingestion in pediatric patients: What may lie ahead. Pediatr Emerg Care 2020;36:e349-e354. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001420.

6. Boros CA, Parsons DW, Zoanetti GD, et al. Cannabis cookies: A cause of coma. J Paediatr Child Health 1996;32:194-195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.1996.tb00922.x.

7. Cesbron A, Tokayeva L, Loilier M, et al. Severe accidental cannabis poisoning in a 16-month-old girl. 19th annual meeting of French Society of Pharmacology and Therapeutics, Caen, France. Abstract PS1-040. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 2015;29(Suppl 1):55.

8. Chaib N, Ameur S, Negadi MA. Cannabis poisoning in infants: A case report. 10th World Congress of the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies, WFPICCS 2020. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2021;22(Suppl 1):261. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pcc.0000740420.25164.78.

9. Chartier C, Penouil F, Blanc-Brisset I, et al. Pediatric cannabis poisonings in France: More and more frequent and severe. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2021;59:326-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2020.1806295.

10. Claudet I, Le Breton M, Bréhin C, Franchitto N. A 10-year review of cannabis exposure in children under 3-years of age: Do we need a more global approach? Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:553-556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-017-2872-5.

11. Claudet I, Mouvier S, Labadie M, et al. Unintentional cannabis intoxication in toddlers. Pediatrics 2017;140:e20170017. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0017.

12. Cohen N, Galvis Blanco L, Davis A, et al. Pediatric cannabis intoxication trends in the pre and post-legalization era. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2022;60:53-58. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2021.1939881.

13. Coret A, Rowan-Legg A. Unintentional cannabis exposures in children pre- and post-legalization: A retrospective review from a Canadian paediatric hospital. Paediatr Child Health 2022;27:265-271. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxab090.

14. Crevani M, Schicchi A, Vecchio S, et al. Electroencephalogram (EEG) alterations during tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) ingestion in children: A case series. 38th International Congress of the European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) 22–25 May 2018, Bucharest, Romania. Clin Toxicol 2018;56:453-608. Abstract 227. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2018.1457818.

15. Guidet C, Gregoire M, Le Dreau A, et al. Cannabis intoxication after accidental ingestion in infants: Urine and plasma concentrations of ∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), THC-COOH and 11-OH-THC in 10 patients. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2020;58:421-423. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1655569.

16. Heizer JW, Borgelt LM, Bashqoy F, et al. Marijuana misadventures in children: Exploration of a dose-response relationship and summary of clinical effects and outcomes. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018;34:457-462. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000770.

17. Herbst J, Musgrave G. Respiratory depression following an accidental overdose of a CBD-labeled product: A pediatric case report. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash DC) 2020;60:248-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2019.09.023.

18. Huntington S, Vohra R, Brown K, Zamanpour E. Pediatric exposures related to medical marijuana: A Poison control perspective. American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting, ACMT 2019. J Med Toxicol 2019;15:53-107. Abstract 144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-019-00699-x.

19. Kaczor EE, Mathews B, LaBarge K, et al. Pediatric cannabis product ingestions: Ranges of exposure effects and outcomes. 2021 American College of Medical Toxicology Annual Scientific Meeting, ACMT. J Med Toxicol 2021;17:93-153. Abstract 080. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-021-00832-9.

20. Khandhar P, Lim J, Steck M. Weetos: Edible cannabinoids and a child with lethargy. 48th Critical Care Congress of the Society of Critical Care Medicine, SCCM 2019. San Diego, CA. Crit Care Med 2019;47(Suppl 1). Abstract 795.

21. Lanzi C, Baldereschi G, Ounalli H, et al. Altered mental status at the emergency department. Clinical management of acute tetrahydrocannabinol oral exposure by the Florence Poison Control center: A case series. 42nd International Congress of the European Association of Poisons Centres and Clinical Toxicologists (EAPCCT) 24-27 May 2022, Tallinn, Estonia. Clin Toxicol 2022;60:sup1,1-108. Abstract 36. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2022.2054576.

22. Lapeyre-Mestre M, Chauvin E, Jouanjus E, et al. Cannabis exposure in young children: Increasing rate of hospitalisation in France in the recent years. 13th Congress of the European Association for Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, EACPT 2017. Prague, Czechia. Clin Ther 2017;39(Suppl 1):e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2017.05.041.

23. Leonard JB, Laudone T, Quaal Hines E, et al. Critical care interventions in children aged 6 months to 12 years admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit after unintentional cannabis exposures. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2022;60:960-965. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2022.2059497.

24. Leubitz A, Spiller HA, Jolliff H, Casavant M. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of unintentional ingestion of marijuana in children younger than 6 years in states with and without legalized marijuana laws. Pediatr Emerg Care 2021;37:e969-e973. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001841.

25. Levene RJ, Pollak-Christian E, Wolfram S. A 21st century problem: Cannabis toxicity in a 13-month-old child. J Emerg Med 2019;56:94-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.09.040.

26. Lovecchio F, Heise CW. Accidental pediatric ingestions of medical marijuana: A 4-year poison center experience. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:844-845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2015.03.030.

27. Macnab A, Anderson E, Susak L. Ingestion of cannabis: A cause of coma in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 1989;5:238-239. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006565-198912000-00010.

28. Mahonski S, Barney N, Hoots B, et al. Unintentional pediatric cannabis exposures reported to a single poison control center: A comparison of outcomes of confirmed cannabis ingestions to unconfirmed cannabis ingestions. North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT). Clin Toxicol 2022;60:sup2,1-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2022.2107776.

29. Mattimoe C, Conlon E, Ní Siocháin D, et al. Edible cannabis toxicity in young children; An emergent serious health threat. Ir Med J 2021;114:446.

30. Mehamha H, Doudka N, Minodier P, et al. Unintentional cannabis poisoning in toddlers: A one year study in Marseille. Forensic Sci Int 2021;325:110858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2021.110858.

31. Morini L, Quaiotti J, Moretti M, et al. Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinolic acid A (THC-A) in urine of a 15-month-old child: A case report. Forensic Sci Int 2018;286:208-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2018.03.020.

32. Murray D, Olson J, Lopez AS. When the grass isn’t greener: A case series of young children with accidental marijuana ingestion. CJEM 2016;18:480-483. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2015.44.

33. Noble MJ, Hedberg K, Hendrickson RG. Acute cannabis toxicity. Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2019;57:735-742. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2018.1548708.

34. Pélissier F, Claudet I, Pélissier-Alicot A-L, Franchitto N. Parental cannabis abuse and accidental intoxications in children: Prevention by detecting neglectful situations and at-risk families. Pediatr Emerg Care 2014;30:862-866. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000288.

35. Pettinger G, Duggan MB, Forrest AR. Black stuff and babies. Accidental ingestion of cannabis resin. Med Sci Law 1988;28:310-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580248802800409.

36. Richards JR, Smith NE, Moulin AK. Unintentional cannabis ingestion in children: A systematic review. J Pediatr 2017;190:142-152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.07.005.

37. Robinson K. Beyond resinable doubt? J Clin Forensic Med 2005;12:164-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcfm.2004.10.014.

38. Schwarz E. Asystole complicating a pediatric cannabinoid exposure. North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Abstracts 2018. Clin Toxicol 2018;56:10,912-1092. Abstract 227. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2018.1506610.

39. Shukla PC, Moore UB. Marijuana-induced transient global amnesia. South Med J 2004;97:782-784. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007611-200408000-00022.

40. Silva A, Parsh B. Pediatric emergency: Unintended marijuana ingestion. Nursing 2014;44:12-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NURSE.0000454961.56762.d6.

41. Spyres M, Ruha AM, Finkelstein Y, et al. Peidatric marijuana ingestions: The ToxIC experience 2010-2016. North American Congress of Clinical Toxicology (NACCT) Abstracts. Clin Toxicol 2017;55:7,689-868. Abstract 188. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1348043.

42. Tan Z, Morris V. Cannabis baby. 10th Europaediatrics Congress. Zagreb, Croatia. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2021;106(Suppl 2):A146. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2021-europaediatrics.348.

43. Thomas AA, Von Derau K, Bradford MC, et al. Unintentional pediatric marijuana exposures prior to and after legalization and commercial availability of recreational marijuana in Washington State. J Emerg Med 2019;56:398-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.01.004.

44. Wang GS, Roosevelt G, Heard K. Pediatric marijuana exposures in a medical marijuana state. JAMA Pediatr 2013;167:630-633. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.140.

45. Weinberg D, Lande A, Hilton N, Kerns DL. Intoxication from accidental marijuana ingestion. Pediatrics 1983;71:848-850.

46. Yeung MEM, Weaver CG, Hartmann R, et al. Emergency department pediatric visits in Alberta for cannabis after legalization. Pediatrics 2021;148:e2020045922. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-045922.

Studies referenced per clinical category discussed (see Table S3 for citations)

i. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46.

ii. 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 21, 23, 27, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38, 41, 42, 45, 46.

iii. 5, 9, 11, 12, 13, 18, 16, 23, 33, 36, 41.

iv. 1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 23, 25, 27, 29, 30, 32, 33, 36, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46.

v. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 45, 46.

vi. 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 46.

vii. 2, 5, 9, 11, 16, 21, 24, 32, 33, 39, 41.

viii. 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 13, 16, 19, 20, 25, 26, 28, 31, 32, 36, 40, 42, 45, 46.

ix. 2, 6, 9, 11, 13, 23, 24, 26, 27, 30, 33, 36, 38.

x. 2, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 19, 21, 23, 24, 25, 28, 29, 30, 33, 38, 41.

xi. 7, 9, 11, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 29, 33, 35, 36, 40, 41, 45, 46.

xii. 2, 5, 9, 13, 16, 24, 26, 30, 33, 36.

xiii. 2, 7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 16, 27, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36, 42, 46.

xiv. 1, 6, 9, 25, 27, 30, 34, 46.

xv. 1, 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 13, 16, 24, 26, 27, 29, 36, 39, 45, 46.

xvi. 2, 6, 8, 14, 15, 24, 25, 27, 29, 30, 31, 34, 36.

xvii. 1, 2, 5, 9, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 24, 29, 30, 33, 34, 36, 39, 41.

xviii. 2, 9, 11, 13, 15, 16, 23, 29, 33, 34, 36, 39, 40, 41.

xix. 2, 9, 13, 23, 30, 33, 36.

xx. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 22, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45, 46.

xxi. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 21, 22, 25, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45.

xxii. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 15, 25, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45.

xxiii. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 13, 14, 14, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45.

xxiv. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 44, 45.

xxv. 11, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 46.

xxvi. 11, 12, 13, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 46.

xxvii. 11, 12, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 46.

xxviii. 11, 21, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 46.

xxix. 11, 14, 25, 27, 29, 31, 32, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 45, 46.

xxx. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45.

xxxi. 5, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 33, 34, 43, 44, 45.

xxxii. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 29, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45.

xxxiii. 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 20, 22, 23, 24, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 36, 43, 44.

xxxiv. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 17, 19, 23, 24, 28, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

xxxv. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14, 15, 23, 24, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

xxxvi. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 23, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

xxxvii. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

xxxix. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 14, 15, 23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

xl. 1.

xli. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19, 23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 46.

Dr Sage is a pediatric resident physician at the University of British Columbia. Dr Alahmadi recently completed a pediatric emergency medicine fellowship at UBC and is now an attending physician at Prince Mohammed Bin Abdulaziz Hospital in Madinah, Saudi Arabia. Dr Sabhaney is an attending emergency medicine physician at BC Children’s Hospital, research director of pediatric emergency medicine at BC Children’s, and a clinical assistant professor at UBC. Dr Moe is an attending emergency medicine physician at Vancouver General Hospital and BC Children’s, scientific director of the Emergency Opioid Innovation Program at Emergency Care BC, an assistant professor with the Department of Emergency Medicine at UBC, and a clinician scientist with the BC Centre for Disease Control.

Corresponding author: Dr Adam P. Sage, adam.sage@phsa.ca.