Managing hyperkalemia in the outpatient setting

ABSTRACT: Hyperkalemia, a common electrolyte (potassium) abnormality, is often encountered in the outpatient setting, but the lack of standardized guidelines for hyperkalemia management creates challenges for both patients and health care providers. We reviewed the causes of hyperkalemia based on common case presentations, highlighting potassium physiology, contributing medications and comorbidities, and laboratory and sampling factors. Outpatient management of hyperkalemia involves assessing the patient’s intercurrent health, reviewing their medications to identify potential culprits, addressing comorbidities, and, if necessary, initiating the use of additional medications (e.g., diuretics, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors) to manage underlying conditions. It is important to exhaust all options before discontinuing or reducing doses of guideline-directed medications such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Updated recommendations for dietary management of potassium emphasize reducing the intake of highly bioavailable potassium in processed foods and salts rather than restricting fresh fruits and vegetables, plant-based proteins, and whole grains.

Outpatient management of hyperkalemia involves assessing the patient’s intercurrent health, reviewing their medications, addressing comorbidities, and initiating additional medications if necessary. Patients should avoid processed foods and salts with highly bioavailable potassium.

Hyperkalemia is a common electrolyte abnormality among patients with cardio-kidney-metabolic syndrome and has potentially life-threatening consequences.[1-3] Hyperkalemia is more commonly seen in patients with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and diabetes, given the underlying pathophysiology and exposure to guideline-based medications such as renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors (RAASis) and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs).[4,5] However, despite well-established recommendations for managing acute hyperkalemia in inpatient settings, guidelines for outpatient management remain limited.[6] Available data and recommendations are often extrapolated from the inpatient setting, where the severity of concomitant illnesses in hospitalized patients may lead to recommendations for outpatients to be referred to the emergency department for monitoring.[5] These broad-stroke recommendations create further stress and anxiety for the patient, physician, and health care system. Given the association of hyperkalemia with higher health care resource utilization and costs, clear protocols are needed.[7,8] We present clinical cases that highlight common scenarios in which a clinician may encounter hyperkalemia in the outpatient setting. We review risk factors, potential causes, and suggested approaches to outpatient management.

Case 1

Mr Sharma is a 65-year-old man with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension. His most recent blood work indicated his potassium level was 5.2 mmol/L, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 80 ml/min/1.73 m2, urine albumin:creatinine ratio was 40 mg/mmol, and A1c was 8.1%. He takes telmisartan, amlodipine, atorvastatin, empagliflozin, metformin, and insulin. He also takes glucosamine daily and ibuprofen as needed for management of osteoarthritis. His blood pressure is 140/85 mmHg. Two weeks after increasing his telmisartan dose to 80 mg daily, his serum potassium was 5.9 mmol/L. What are his risk factors for hyperkalemia?

Factors affecting potassium levels

Potassium physiology

Approximately 98% of total body potassium is stored intracellularly, while 2% is in serum.[9] In normal kidney function, the kidney is responsible for approximately 90% of potassium excretion, while colonic excretion accounts for approximately 10%.[10] This intra- and extracellular difference in potassium levels is maintained by several complex mechanisms, including sodium–potassium pumps and hormonal regulation. Cellular uptake of potassium is influenced by insulin and beta2 adrenergic receptor stimulation, while renal excretion of potassium is modulated by aldosterone. In people with reduced eGFR, adaptations occur to maintain potassium homeostasis: the kidney adaptively increases potassium secretion in the remaining functioning nephrons, and gastrointestinal potassium excretion increases to up to 25% to 30% of total excretion in the case of G5 chronic kidney disease.[9,11]

Serum potassium follows a circadian rhythm whereby potassium levels peak in the early afternoon and reach a nadir at 9 p.m.[12] The diurnal variability of serum potassium is much greater in the setting of chronic kidney disease (the difference between minimum and maximum potassium levels in an individual is 0.72 ± 0.45 mmol/L) compared with normal kidney function.[12] Patients with chronic kidney disease commonly exhibit postprandial hyperkalemia with serum potassium transiently rising following a meal—this is referred to as “impaired potassium tolerance.”[13]

Medications and comorbidities

Hyperkalemia has multifactorial causes [Figure 1].[13] Patients with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, or diabetes are commonly prescribed medications that further reduce renal potassium excretion (e.g., RAASis, MRAs) or block intracellular uptake (e.g., beta blockers). Over-the-counter medications such as NSAIDs and supplements such as glucosamine also raise serum potassium, either by reducing potassium clearance (e.g., NSAIDs) or, more commonly, by containing potassium additives.[14]

Hyperkalemia has multifactorial causes [Figure 1].[13] Patients with chronic kidney disease, heart failure, or diabetes are commonly prescribed medications that further reduce renal potassium excretion (e.g., RAASis, MRAs) or block intracellular uptake (e.g., beta blockers). Over-the-counter medications such as NSAIDs and supplements such as glucosamine also raise serum potassium, either by reducing potassium clearance (e.g., NSAIDs) or, more commonly, by containing potassium additives.[14]

Constipation, which occurs in up to 90% of patients on dialysis, is a common contributor to hyperkalemia because of the increased reliance on gastrointestinal potassium excretion in chronic kidney disease.[15] Diabetes mellitus is another risk factor for hyperkalemia, as hyporeninemic hypoaldosteronism is commonly seen in these patients, and intracellular shift of potassium is reduced in the setting of hyperglycemia and low insulin states.[13] Cellular uptake of potassium is also reduced with metabolic acidosis, a complication of advanced chronic kidney disease. Renal hypoperfusion in the setting of volume depletion and heart failure also increases the risk of hyperkalemia. Finally, concurrent illnesses associated with increased catabolism or tissue breakdown can cause increased release of potassium into the extracellular space. Despite common understanding to the contrary, dietary potassium intake has a weak correlation with blood potassium.

Laboratory and sampling factors

Collection methods and sample handling may contribute to variability in serum potassium. Levels in serum samples are often higher than those in plasma (by a mean of 0.38 ± 0.18 mmol/L) because serum analysis requires the blood to clot, which releases potassium, whereas plasma samples do not.[16] Similarly, pseudohyperkalemia may occur due to clotted samples, traumatic venipuncture, fist clenching, suboptimal temperature of sample storage, high levels of platelets, and delayed sample processing.[17]

Case 1 revisited

Mr Sharma has several risk factors for hyperkalemia. He has diabetes, and suboptimal glycemic control can result in a shift of potassium to the extracellular space. His over-the-counter medications, ibuprofen and glucosamine, are also likely contributors to hyperkalemia.

Given his albuminuria, the goal would be to achieve the maximum tolerated dose of his angiotensin receptor blocker (i.e., maintain his current telmisartan dose). He should be counseled to avoid NSAIDs and glucosamine. A thiazide/thiazide-like diuretic could be added, given that he has suboptimal blood pressure control, and this medication can increase potassium excretion. To improve his glycemic control and enhance potassium shift into cells, his insulin dose can be increased, and/or a glucagon-like peptide-1 agonist, which also has kidney and cardiovascular benefits, can be considered.[18]

Case 2

Ms Lee is a 68-year-old woman who was recently discharged from hospital with myocardial infarction requiring three stents, subsequent heart failure with an ejection fraction of 35%, and chronic kidney disease with a baseline eGFR of 23 mL/min/1.73 m2. Her medications include aspirin, bisoprolol, atorvastatin, sacubitril/valsartan, and dapagliflozin. She was recently seen in the clinic and was started on spironolactone. Her previous potassium levels were 5.3 mmol/L and 4.8 mmol/L. You receive a call from the outpatient lab in the evening because blood work from a sample drawn earlier in the day indicated a potassium level of 6.3 mmol/L.

Critical hyperkalemia: When should patients go to the emergency department?

There are several key factors in determining the severity of hyperkalemia: signs and symptoms, potassium level, and the rate of change in potassium levels. Irrespective of the potassium level, anyone with signs and symptoms such as muscle weakness or paralysis or cardiac conduction abnormalities or arrhythmias requires emergency treatment and cardiac monitoring.[19-22] The most common electrocardiogram findings in hyperkalemia are peaked T waves followed by QRS widening; sustained hyperkalemia may further lead to conduction blocks, ventricular fibrillation, and asystole.[20] Guidelines and expert opinion agree that anyone with a potassium level greater than 6.5 mmol/L should be urgently referred to the emergency department, but there are discrepancies regarding management of potassium levels between 6.0 and 6.5 mmol/L.[5,20-22] This range requires clinical judgment and contextualization of potassium values due to the multifactorial nature of outpatient measurements [Figure 1]. Furthermore, the rate of change in potassium levels must be considered, because a rapid rise is more likely to cause cardiac abnormalities than a gradual increase over several months.[21]

Without clear guidelines and standardization, physicians must use their clinical judgment to decide when to send patients to the emergency department, which increases stress and anxiety for clinicians and patients and further strains the health care system. In British Columbia, LifeLabs alerts clinicians anytime potassium levels are greater than 6.2 mmol/L. In comparison, in Ontario, clinicians are alerted anytime potassium levels are greater than 6.6 mmol/L, but only between 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. when levels are 6.2 to 6.5 mmol/L.[23,24] Lab results are often reported after hours, and patients exhibit no symptoms, which further adds to the management conundrum.

Outpatient management of hyperkalemia

Patient assessment and review of medications

Assessing the patient’s intercurrent health is an essential first step to determining whether the hyperkalemia can be managed when the individual is an outpatient. Patients with severe intercurrent illness with concurrent metabolic derangements (e.g., pneumonia with dehydration leading to acute kidney injury and hyperkalemia) or symptoms of hyperkalemia require urgent medical care. Once the patient is deemed stable, the recommended approach is to first address modifiable factors and apply mitigating strategies [Figure 1]. A careful review of medications may identify a potential culprit. Discontinuing over-the-counter medications such as NSAIDs and glucosamine supplements may resolve hyperkalemia. A repeat lab test outside the postprandial window and discontinuing culprit medications can often resolve hyperkalemia and clarify potential contributing laboratory factors.

Addressing comorbidities

In patients with diabetes, hyperkalemia may result from potassium shift due to elevated serum glucose.[25] Management of the hyperglycemia can improve serum potassium levels. Correction of metabolic acidosis in patients with chronic kidney disease by increasing fruit and vegetable intake or bicarbonate supplementation can improve hyperkalemia.[26,27] However, sodium bicarbonate supplementation needs to be monitored in individuals with a history of heart failure, because it can lead to volume overload.[28] Addressing constipation with laxatives and increasing fibre intake can improve gastrointestinal potassium clearance.[20] The following resource highlights the management of constipation, including both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic strategies, in patients with chronic kidney disease:

Additional medications

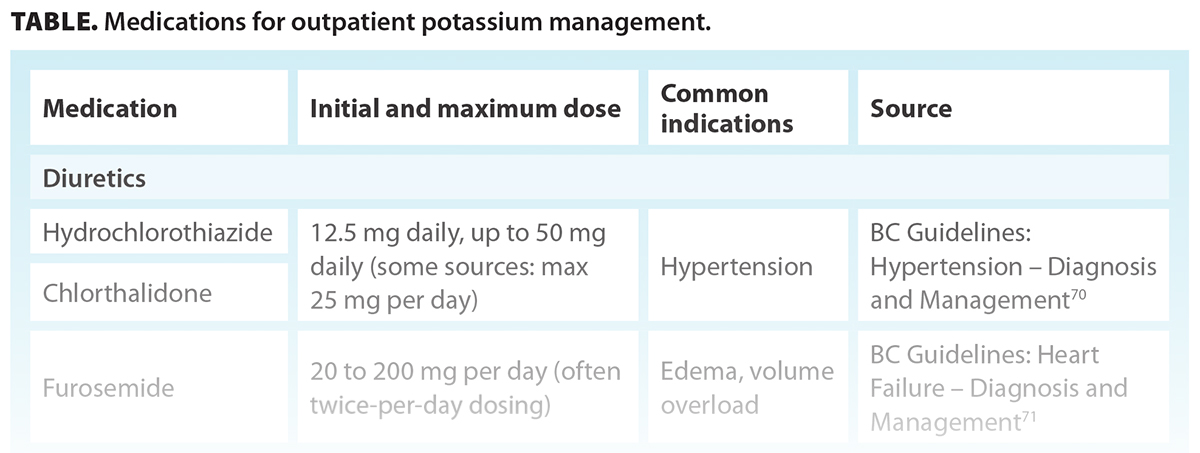

The primary purpose of initiating additional medications (e.g., diuretics, sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors) is to manage underlying conditions, such as hypertension or heart failure, with the secondary benefit of mitigating hyperkalemia through their mechanisms of action. If the addition of a medication is not sufficient to manage hyperkalemia, a potassium binder can be added. The Table provides examples of medications and possible doses; however, medication selection, initial dosing, and titration must be individualized for each patient in consideration of clinical indication, adverse effect profile, and tolerability.

Diuretics

For patients with persistent hyperkalemia in the setting of chronic kidney disease and/or hypertension/volume overload, a thiazide/thiazide-like or loop diuretic can enhance kidney excretion of potassium.[20] However, their effectiveness diminishes and becomes less predictable in patients with low kidney function and chronic use; thus, dose titration is required.[20,28]

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors, which have been shown to reduce the risk of kidney disease progression and cardiovascular events, also reduce the risk of serious hyperkalemia.[29] They promote potassium excretion by increasing the delivery of sodium to the distal tubules in the kidneys.[30] However, the extent of sodium and potassium excretion is uncertain.[31]

Potassium binders

Potassium binders are potential management options for persistent hyperkalemia (potassium levels above 5.5 mmol/L) that is not responsive to other measures. In a recent study of BC patients with chronic kidney disease, only about 27% of patients with persistent hyperkalemia were prescribed sodium polystyrene sulfonate or calcium resonium.[32] Gastrointestinal side effects and palatability may limit the long-term use of these potassium binders. However, newer agents such as sodium zirconium cyclosilicate and patiromer are available, but real-world studies are needed to assess whether tolerability is improved compared with the older potassium binders. Studies suggest that these newer potassium binders allow patients to remain on RAASis in the treatment of chronic kidney disease and heart failure.[33,34]

Consequences of discontinuing guideline-directed medical therapies

RAASis and MRAs are both key disease-modifying agents for treating chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes mellitus.[35-37] They lead to increases in potassium concentration due to their interference with aldosterone (indirect and direct blockade), thus impairing excretion by the kidney. They are often down-titrated or discontinued when patients experience hyperkalemia.[38] Observational studies, systematic reviews, and RCTs have demonstrated that discontinuing RAASis is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality and increased risk of kidney failure requiring dialysis.[39-41] Similar outcomes have been observed when discontinuing RAASis in patients with restored left ventricular heart failure after an acute myocardial infarction: stopping RAASis was associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, spontaneous myocardial infarction, and heart failure rehospitalization (11.4% vs 5.4%; hazard ratio 2.20 [95% CI, 1.09-4.46]).[42] Only as a last resort should dose reductions or discontinuation of RAASis or MRAs be considered if there is uncontrolled hyperkalemia despite addressing modifiable factors/medical treatment.[26,43] If these medications are withheld, it is important to try to reintroduce them, with additional emphasis on addressing factors highlighted in Figure 1.

Case 2 revisited

Ms Lee tells you she has been feeling well, is taking her medications as prescribed, and has not started any new over-the-counter supplements. She has been eating and drinking well and having regular bowel movements. Both you and Ms Lee are keen on continuing her guideline-based medications. You review and provide her with the potassium management patient handout and discuss potentially starting her on a potassium binder. Follow-up blood work the next day indicates a potassium level of 6.0 mmol/L, and you prescribe sodium polystyrene sulfonate 15 g orally daily for 5 days, which reduces her potassium level to 5.5 mmol/L the following week. With dietary changes, Ms Lee could wean off the binder the following week and continue her guideline-directed medical therapies.

New perspectives on low-potassium diets

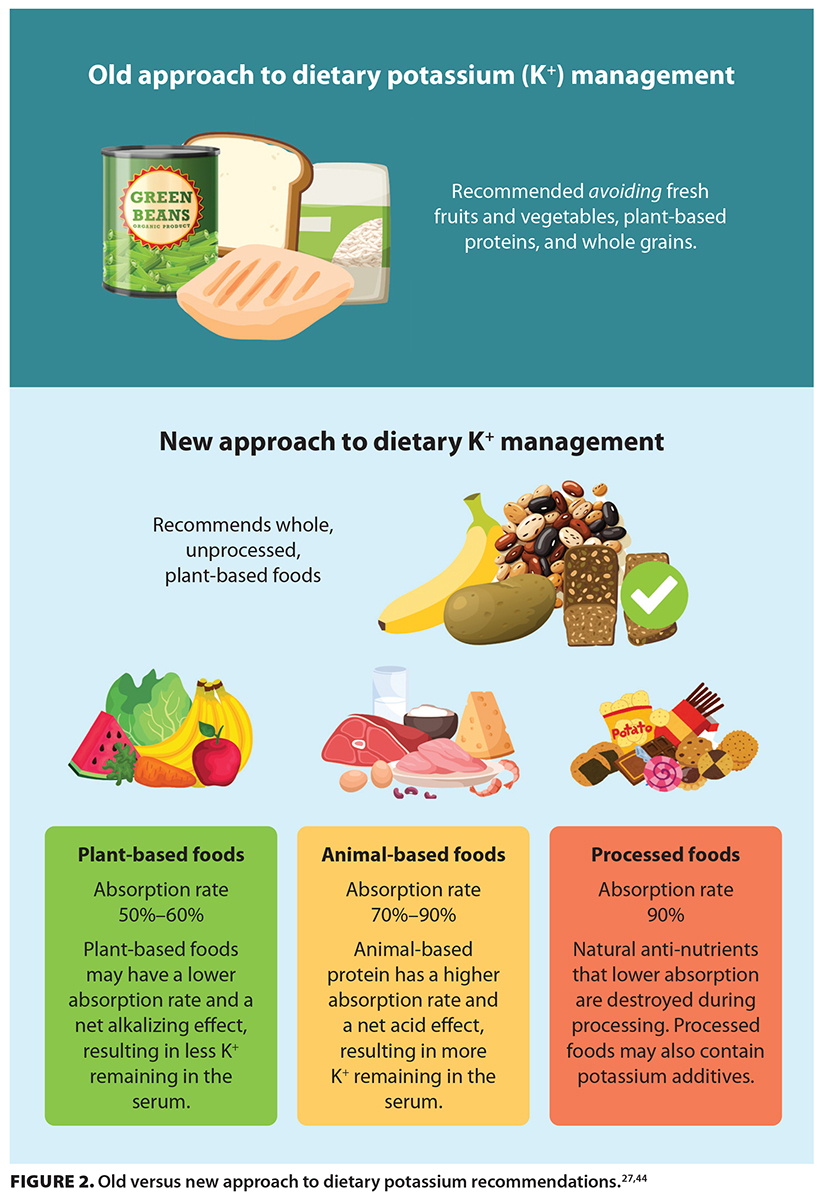

Traditionally, low-potassium diets have focused on restricting whole fruits and vegetables (e.g., bananas, potatoes, oranges) [Figure 2].[44,45] However, increasing evidence indicates that this approach fails to recognize factors such as potassium bioavailability, co-nutrient ingestion impacts on potassium metabolism, and North American dietary patterns.[46-49]

Traditionally, low-potassium diets have focused on restricting whole fruits and vegetables (e.g., bananas, potatoes, oranges) [Figure 2].[44,45] However, increasing evidence indicates that this approach fails to recognize factors such as potassium bioavailability, co-nutrient ingestion impacts on potassium metabolism, and North American dietary patterns.[46-49]

Different foods have different potassium bioavailability.[46] Several studies on potassium balance have reported that plant foods, whose cell walls are left intact, have lower bioavailability than animal products.[50] This has led recent low-potassium diet recommendations to focus less on whole fruits and vegetables, because their intact cell walls likely reduce potassium bioavailability and limit their impact on circulating potassium.

Co-nutrient ingestion also alters intracellular potassium uptake. Alkaline foods, such as whole fruits and vegetables, encourage intracellular potassium uptake more than acidic foods, such as animal proteins.[48,51-53] Additionally, potassium combined with carbohydrate loads enhances intracellular potassium uptake via insulin.[49] This has led to the recognition that whole fruits and vegetables that contain carbohydrates are less likely to be associated with hyperkalemia than animal-based foods.

Finally, the third factor related to changing recommendations also considers North American dietary patterns, particularly the consumption of ultra-processed foods. These foods may contain potassium additives, which have been reported to have significantly higher levels of potassium than foods without additives. These additives tend to be found in foods that have traditionally been considered to be low in potassium.[54-56] Ultra-processed foods are more likely to have altered cell structures, which increases potassium bioavailability, even without additives. These foods also tend to be more acidic and lower in fibre, which may enhance absorption and reduce cellular potassium uptake.[57] An investigation of processed food consumption by adults living with kidney disease reported that more than 60% of calories consumed came from processed and ultra-processed foods.[58] Processed foods also reduce naturally beneficial “anti-nutrients”—compounds that inhibit nutrient absorption—thereby resulting in higher potassium uptake.[59]

What to recommend instead?

New dietary potassium modification recommendations no longer restrict the intake of fresh fruits and vegetables but instead focus modification on highly bioavailable potassium in processed foods. Focusing on nutrient-dense foods that are higher in plant fibre has shifted traditional recommendations away from total milligrams of potassium toward a diet that is higher in nutrient quality and lower in foods that contain potassium additives.[60] Modification of dietary potassium has also adopted a more comprehensive approach that recognizes the variety of factors, including glycemic levels and acid–base balance, that are known to impact serum potassium levels.[61]

If the cause of hyperkalemia is related to acidosis, the primary dietary strategy is to recommend the intake of fruits and vegetables. These foods are base producing and have been shown to improve acidosis in chronic kidney disease.[62,63] Whole, unprocessed fruits and vegetables are preferable to processed fruits and vegetables, such as juices, dried fruits, and canned products that are high in sugar or sodium. In general, a diet that is in line with the dietary approaches for hypertension or a Mediterranean diet, where unprocessed plant foods are favored over others, tends to work favorably for managing potassium levels, as well as overall cardiac health, diabetes, and kidney health.[64-66] Such diets are favorable because of their higher fibre content, which reduces the bioavailability of potassium and improves digestive health.[67-69]

If the primary cause of hyperkalemia is related to glycemic levels, reducing the glycemic index of meals; using low-glycemic-index foods and higher-fibre foods; and consuming a better balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are recommended. If potassium levels remain elevated despite addressing modifiable risk factors and dietary advice is indicated, initial recommendations are to reduce the intake of items with highly concentrated forms of potassium, such as potassium-based salt substitutes, potassium-containing sports drinks, orange- or tomato-based juices, hot chocolate powders, and processed meats (e.g., hot dogs, lunch meat). Encouraging patients to read ingredient lists for potassium additives, including potassium chloride, potassium lactate, and potassium phosphates, is also recommended. Products that contain these additives are likely to contribute significant amounts of potassium to the diet. Finally, wet cooking methods (such as boiling and blanching) can help reduce the potassium content of all foods and are the preferred methods for cooking meats, legumes, grains, and vegetables compared with dry cooking methods (such as baking, roasting, and frying). Two important resources can help support this practice change:

- Potassium Management in Kidney Disease (BC Renal): www.bcrenal.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Potassium_Management_in_Kidney_Disease.pdf

- Optimization of RAASi Therapy Toolkit: Addressing Challenges: Dietary approaches to hyperkalemia (International Society of Nephrology): www.theisn.org/initiatives/toolkits/raasi-toolkit/#1684867542809-330edb79-52b4

Summary

Outpatient hyperkalemia is a common abnormality identified in lab reports to clinicians. This review identifies multiple risk factors and management strategies for outpatient hyperkalemia and offers new perspectives on low-potassium diets. It also highlights the importance of exhausting all options before discontinuing or reducing doses of guideline-directed medications such as RAASis and MRAs.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Dittrich KL, Walls RM. Hyperkalemia: ECG manifestations and clinical considerations. J Emerg Med 1986;4:449-455. https://doi.org/10.1016/0736-4679(86)90174-5.

2. Parham WA, Mehdirad AA, Biermann KM, Fredman CS. Hyperkalemia revisited. Tex Heart Inst J 2006;33:40-47.

3. Larkin H. Here’s what to know about cardiovascular-kidney-metabolic syndrome, newly defined by the AHA. JAMA 2023;330:2042-2043. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2023.22276.

4. Collins AJ, Pitt B, Reaven N, et al. Association of serum potassium with all-cause mortality in patients with and without heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and/or diabetes. Am J Nephrol 2017;46:213-221. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479802.

5. Chiu M, Garg AX, Moist L, Jain AK. A new perspective to longstanding challenges with outpatient hyperkalemia: A narrative review. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2023;10:20543581221149710. https://doi.org/10.1177/20543581221149710.

6. Sterns RH, Grieff M, Bernstein PL. Treatment of hyperkalemia: Something old, something new. Kidney Int 2016;89:546-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2015.11.018.

7. Desai NR, Reed P, Alvarez PJ, et al. The economic implications of hyperkalemia in a Medicaid managed care population. Am Health Drug Benefits 2019;12:352-361.

8. Sharma A, Alvarez PJ, Woods SD, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with hyperkalemia in a large managed care population. J Pharm Health Serv Res 2021;12:35-41. https://doi.org/10.1093/jphsr/rmaa004.

9. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Physiology and pathophysiology of potassium homeostasis: Core curriculum 2019. Am J Kidney Dis 2019;74:682-695. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.03.427.

10. Palmer BF, Colbert G, Clegg DJ. Potassium homeostasis, chronic kidney disease, and the plant-enriched diets. Kidney360 2020;1:65-71. https://doi.org/10.34067/KID.0000222019.

11. Babich JS, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Joshi S. Taking the kale out of hyperkalemia: Plant foods and serum potassium in patients with kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2022;32:641-649. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2022.01.013.

12. Schmidt ST, Ditting T, Deutsch B, et al. Circadian rhythm and day to day variability of serum potassium concentration: A pilot study. J Nephrol 2015;28:165-172.

13. St-Jules DE, Fouque D. Etiology-based dietary approach for managing hyperkalemia in people with chronic kidney disease. Nutr Rev 2022;80:2198-2205. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuac026.

14. John SK, Rangan Y, Block CA, Koff MD. Life-threatening hyperkalemia from nutritional supplements: Uncommon or undiagnosed? Am J Emerg Med 2011;29:1237.e1-1237.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2010.08.029.

15. Sumida K, Yamagata K, Kovesdy CP. Constipation in CKD. Kidney Int Rep 2019;5:121-134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2019.11.002.

16. Nijsten MW, de Smet BJ, Dofferhoff AS. Pseudo-hyperkalemia and platelet counts. N Engl J Med 1991;325:1107. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199110103251515.

17. Asirvatham JR, Moses V, Bjornson L. Errors in potassium measurement: A laboratory perspective for the clinician. N Am J Med Sci 2013;5:255-259. https://doi.org/10.4103/1947-2714.110426.

18. Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, et al. Effects of semaglutide on chronic kidney disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2024;391:109-121. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2403347.

19. El-Sherif N, Turitto G. Electrolyte disorders and arrhythmogenesis. Cardiol J 2011;18:233-245.

20. Clase CM, Carrero J-J, Ellison DH, et al. Potassium homeostasis and management of dyskalemia in kidney diseases: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 2020;97:42-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2019.09.018.

21. Palmer BF, Carrero JJ, Clegg DJ, et al. Clinical management of hyperkalemia. Mayo Clin Proc 2021;96:744-762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.014.

22. Kim MJ, Valerio C, Knobloch GK. Potassium disorders: Hypokalemia and hyperkalemia. Am Fam Physician 2023;107:59-70.

23. LifeLabs British Columbia. Critical laboratory test results – British Columbia. https://lifelabs.azureedge.net/lifelabs-wp-cdn/2021/04/Critical-Laboratory-Test-Results-British-Columbia.pdf.

24. LifeLabs Ontario. Specimen collection and handling instructions: Expedited requests and critical and alert values. https://lifelabs.azureedge.net/lifelabs-wp-cdn/2018/08/expedited-Results-Critical-Alert-Values-.pdf.

25. Viberti GC. Glucose-induced hyperkalæmia: A hazard for diabetics? Lancet 1978;1(8066):690-691. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(78)90801-2.

26. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Hyperkalemia treatment standard. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2024;39:1097-1104. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfae056.

27. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2024;105:S117-S314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2023.10.018.

28. Weinstein J, Girard L-P, Lepage S, et al. Prevention and management of hyperkalemia in patients treated with renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors. CMAJ 2021;193:E1836-E1841. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.210831.

29. Neuen BL, Oshima M, Agarwal R, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and risk of hyperkalemia in people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomized, controlled trials. Circulation 2022;145:1460-1470. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.057736.

30. Gabai P, Fouque D. SGLT2 inhibitors: New kids on the block to control hyperkalemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38:1345-1348. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfad026.

31. Massicotte-Azarniouch D, Canney M, Sood MM, Hundemer GL. Managing hyperkalemia in the modern era: A case-based approach. Kidney Int Rep 2023;8:1290-1300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ekir.2023.04.016.

32. Atiquzzaman M, Birks P, Bevilacqua M, et al. Prescription pattern of cation exchange resins and their efficacy in treating chronic hyperkalemia among patients with chronic kidney diseases: Findings from a population-based analysis in British Columbia, Canada. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2022;9:20543581221137177. https://doi.org/10.1177/20543581221137177.

33. Paolillo S, Basile C, Dell’Aversana S, et al. Novel potassium binders to optimize RAASi therapy in heart failure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med 2024;119:109-117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2023.08.022.

34. Chinnadurai R, Rengarajan S, Budden JJ, et al. Maintaining renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitor treatment with patiromer in hyperkalaemic chronic kidney disease patients: Comparison of a propensity-matched real-world population with AMETHYST-DN. Am J Nephrol 2023;54:408-415. https://doi.org/10.1159/000533753.

35. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2020 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2020;98:S1-S115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2020.06.019.

36. McDonald M, Virani S, Chan M, et al. CCS/CHFS heart failure guidelines update: Defining a new pharmacologic standard of care for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Can J Cardiol 2021;37:531-546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2021.01.017.

37. Diabetes Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Diabetes Canada 2018 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada. Can J Diabetes 2018;42(Suppl 1):S1-S325.

38. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Managing hyperkalemia to enable guideline-recommended dosing of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors. Am J Kidney Dis 2022;80:158-160. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.02.012.

39. Leon SJ, Whitlock R, Rigatto C, et al. Hyperkalemia-related discontinuation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors and clinical outcomes in CKD: A population-based cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2022;80:164-173.e1. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.01.002.

40. Nakayama T, Mitsuno R, Azegami T, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the clinical impact of stopping renin–angiotensin system inhibitor in patients with chronic kidney disease. Hypertens Res 2023;46:1525-1535. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-023-01260-8.

41. Bhandari S, Mehta S, Khwaja A, et al. Renin–angiotensin system inhibition in advanced chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2021-2032. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2210639.

42. Lee SH, Rhee T-M, Shin D, et al. Prognosis after discontinuing renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitor for heart failure with restored ejection fraction after acute myocardial infarction. Sci Rep 2023;13:3539. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30700-1.

43. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Diabetes Work Group. KDIGO 2022 clinical practice guideline for diabetes management in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2022;102:S1-S127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.008.

44. Picard K, Griffiths M, Mager DR, Richard C. Handouts for low-potassium diets disproportionately restrict fruits and vegetables. J Ren Nutr 2021;31:210-214. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2020.07.001.

45. St-Jules DE, Goldfarb DS, Sevick MA. Nutrient non-equivalence: Does restricting high-potassium plant foods help to prevent hyperkalemia in hemodialysis patients? J Ren Nutr 2016;26:282-287. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2016.02.005.

46. Picard K. Potassium additives and bioavailability: Are we missing something in hyperkalemia management? J Ren Nutr 2019;29:350-353. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2018.10.003.

47. Picard K, Mager D, Richard C. How food processing impacts hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia management in chronic kidney disease. Can J Diet Pract Res 2020;81:132-136. https://doi.org/10.3148/cjdpr-2020-003.

48. Passey C. Reducing the dietary acid load: How a more alkaline diet benefits patients with chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2017;27:151-160. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2016.11.006.

49. Joshi S, McMacken M, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Plant-based diets for kidney disease: A guide for clinicians. Am J Kidney Dis 2021;77:287-296. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.10.003.

50. Naismith DJ, Braschi A. An investigation into the bioaccessibility of potassium in unprocessed fruits and vegetables. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2008;59:438-450. https://doi.org/10.1080/09637480701690519.

51. Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo C-H, Wesson DE. A comparison of treating metabolic acidosis in CKD stage 4 hypertensive kidney disease with fruits and vegetables or sodium bicarbonate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;8:371-381. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.02430312.

52. Goraya N, Raphael KL, Wesson DE. Alkalization to retard progression of chronic kidney disease. In: Nutritional Management of Renal Disease. 4th ed. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press; 2022. pp. 297-309. http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818540-7.00039-2.

53. Banerjee T, Tucker K, Griswold M, et al. Dietary potential renal acid load and risk of albuminuria and reduced kidney function in the Jackson Heart Study. J Ren Nutr 2018;28:251-258. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2017.12.008.

54. Picard K, Picard C, Mager DR, Richard C. Potassium content of the American food supply and implications for the management of hyperkalemia in dialysis: An analysis of the Branded Product Data-base. Semin Dial 2024;37:307-316. https://doi.org/10.1111/sdi.13007.

55. Parpia AS, Goldstein MB, Arcand J, et al. Sodium-reduced meat and poultry products contain a significant amount of potassium from food additives. J Acad Nutr Diet 2018;118:878-885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2017.10.025.

56. Sherman RA, Mehta O. Phosphorus and potassium content of enhanced meat and poultry products: Implications for patients who receive dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1370-1373. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.02830409.

57. Martínez-Pineda M, Vercet A, Yagüe-Ruiz C. Are food additives a really problematic hidden source of potassium for chronic kidney disease patients? Nutrients 2021;13:3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13103569.

58. Picard K, Senior PA, Adame Perez S, et al. Low Mediterranean diet scores are associated with reduced kidney function and health related quality of life but not other markers of cardiovascular risk in adults with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2021;31:1445-1453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2021.02.002.

59. Petroski W, Minich DM. Is there such a thing as “anti-nutrients”? A narrative review of perceived problematic plant compounds. Nutrients 2020;12:2929. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12102929/.

60. St-Jules DE, Fouque D. Is it time to abandon the nutrient-based renal diet model? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2021;36:574-577. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfaa257.

61. Sumida K, Biruete A, Kistler BM, et al. New insights into dietary approaches to potassium management in chronic kidney disease. J Ren Nutr 2023;33:S6-S12. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2022.12.003.

62. Goraya N, Munoz-Maldonado Y, Simoni J, Wesson DE. Treatment of chronic kidney disease-related metabolic acidosis with fruits and vegetables compared to NaHCO3 yields more and better overall health outcomes and at comparable five-year cost. J Ren Nutr 2021;31:239-247. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jrn.2020.08.001.

63. Goraya N, Munoz-Maldonado Y, Simoni J, Wesson DE. Fruit and vegetable treatment of chronic kidney disease-related metabolic acidosis reduces cardiovascular risk better than sodium bicarbonate. Am J Nephrol 2019;49:438-448. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500042.

64. Hu EA, Coresh J, Anderson CAM, et al. Adherence to healthy dietary patterns and risk of CKD progression and all-cause mortality: Findings from the CRIC (Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort) Study. Am J Kidney Dis 2021;77:235-244. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.04.019.

65. Banerjee T, Crews DC, Tuot DS, et al. Poor accordance to a DASH dietary pattern is associated with higher risk of ESRD among adults with moderate chronic kidney disease and hypertension. Kidney Int 2019;95:1433-1442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2018.12.027.

66. Gutiérrez OM, Muntner P, Rizk DV, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of death and progression to ESRD in individuals with CKD: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:204-213. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.02.013.

67. Sidhu SRK, Kok CW, Kunasegaran T, Ramadas A. Effect of plant-based diets on gut microbiota: A systematic review of interventional studies. Nutrients 2023;15:1510. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15061510.

68. Ceccanti C, Guidi L, D’Alessandro C, Cupisti A. Potassium bioaccessibility in uncooked and cooked plant foods: Results from a static in vitro digestion methodology. Toxins (Basel) 2022;14:668. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxins14100668.

69. Babich JS, Dupuis L, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Joshi S. Hyperkalemia and plant-based diets in chronic kidney disease. Adv Kidney Dis Health 2023;30:487-495. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.akdh.2023.10.001.

70. BC Ministry of Health. Hypertension—Diagnosis and management. BC Guidelines. Accessed 6 November 2024. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/hypertension.

71. BC Ministry of Health. Heart failure—Diagnosis and management. BC Guidelines. Accessed 6 November 2024. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/bc-guidelines/heart-failure-chronic.

Dr Yi is a nephrologist in the Division of Nephrology at the University of British Columbia and a clinical researcher at BC Renal, Vancouver. Dr Wong is a nephrologist and clinical assistant professor in the Division of Nephrology at UBC and a clinical researcher at BC Renal, Vancouver. Dr Picard is a registered dietitian with Island Health Authority and BC Renal, Vancouver. Ms Renouf is a registered dietitian with Providence Health Care and BC Renal, Vancouver. Dr Levin is the division head in the Division of Nephrology at UBC and the executive director at BC Renal, Vancouver.