Caring for the sexual lives of community patients living with dementia

Abstract

Research indicates that most couples that include a partner living with dementia consider sex to be of similar importance as couples without cognitive challenges. Additionally, preliminary evidence suggests that continuing sexual activity may slow cognitive decline. However, physicians rarely discuss sexual concerns in this population. Increasing cognitive difficulties and ever-changing personalities compound the frequent age-related vascular, hormonal, and sexual dysfunction; thus, dysfunctions that are complex and different from similarly aged cognitively well persons are likely. Aside from a focus on inappropriate sexual behavior, information on the complexities of their sexual dysfunction or its optimal treatment is minimal, especially in community-dwelling populations. To address this deficit, we discuss ways to open the conversation, offer suggestions for interventions by community physicians, and confirm currently available assistance for physicians about sexual medicine.

A discussion of ways to open the conversation between physicians and their patients, suggestions for interventions by community physicians, and assistance for physicians about sexual medicine.

It is now more widely recognized that many older people retain sexual enjoyment and desire for a sexual life, but this is rarely applied to those living with dementia.[1] Similarly, many physicians will inquire about sexual problems associated with chronic illness but exclude dementia. Data from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP), which included assessment of community-dwelling couples’ cognition and sexuality in 3196 men and women, found that only 1.4% of the 315 women and 17% of the 264 men with dementia had spoken about sex with a doctor.[2] Only very recently has there been more understanding and acceptance that people with dementia are still sexual beings with ongoing desire for sexual intimacy as well as affection and emotional connection.[3]

There may be an assumption that sex would not be important or that dementia would so challenge emotional intimacy that, at least for the well partner, sexual activity would be unwanted. Certainly, emotional intimacy is identified as a major sexual motivation for men and women,[4] and deterioration of cognition and changes in personality and roles may have a severe impact. No longer knowing who the well partner is but wanting sex with them can be particularly distressing.

Negating such assumptions, using a slightly abbreviated version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and a cutoff score of 18 to indicate a probable degree of dementia, the NSHAP researchers found marked sexual resilience for couples where one or both partners were living with dementia. For them, the importance and frequency of sex, a wish for more sexual interaction, and the prevalence of sexual dysfunction were similar to couples without cognitive loss. Moreover, couples challenged with dementia were more likely to continue their sexual lives despite having a sexual dysfunction.[2] Our hesitancy to broach this topic with our patients is misplaced.

We aim to encourage physicians to inquire about and address sexuality as part of their patients’ global health. We outline evidence for the desire for rewarding sexual lives expressed by community-dwelling patients living with dementia, the limited understanding of likely complex sexual dysfunction in this population (driven in part by its usual omission by health care providers), and evidence of the relationship between one’s sexual life and cognition.

Difficulties in long-term care facilities posed by sex-negative attitudes from staff, concerns for privacy, and the safety of patients and other residents are beyond the scope of this article. For reviews on this topic, see the following resources:

- Makimoto K, Kang HS, Yamakawa M, Konno R. An integrated literature review on sexuality of elderly nursing home residents with dementia. Int J Nurs Pract 2015;21(Suppl 2):80-90. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12317.

- Villar F, Celdrán M, Serrat R, et al. Staff’s reactions towards partnered sexual expressions involving people with dementia living in long‐term care facilities. J Advanced Nurs 2018;74:1189-1198. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13518.

Literature review

Aside from some studies on inappropriate sexual behavior, the literature on the sexual lives of community-dwelling couples living with dementia is limited. Some of the few much smaller studies identified increased sexual dysfunction, increased sexual dissatisfaction (especially for the well partner), and cessation of partnered sex than did NSHAP.[5] Dementia-related apathy may extend to sexual apathy,[6] but some research identified both partners’ dissatisfaction with their sexual infrequency.[7]

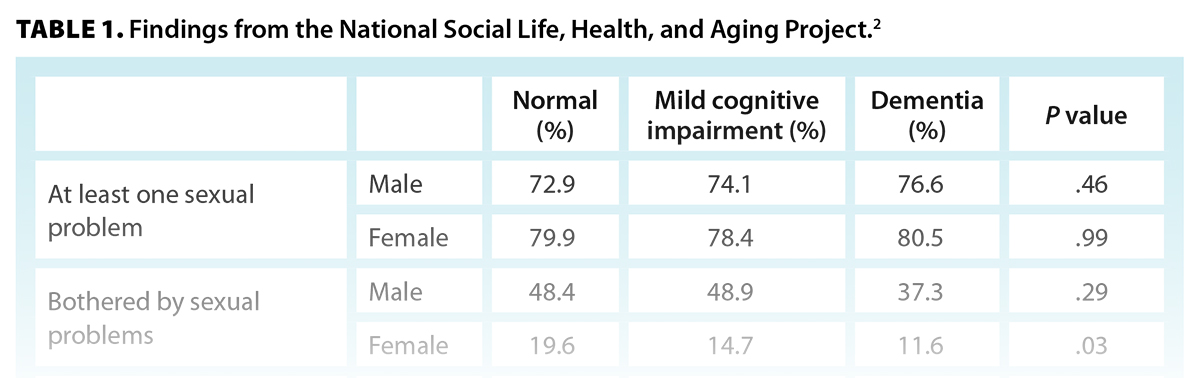

In the second wave of NSHAP in 2011, 1598 couples from the first wave in 2006 were reassessed. Of note are ongoing sexual activity and the importance of sex despite cognitive decline, not only in those whose MoCA scores suggested mild cognitive impairment, but also for those whose scores indicated probable dementia. The findings of the NSHAP study are summarized in Table 1.

Unlike partnered sex (i.e., sex in the context of affection and intimacy), self-stimulation decreased in those with cognitive deficits.[8] This reflects the current understanding of human sexual response,[9,10] which acknowledges many intimacy-related incentives for partnered sex.[4]

Certainty about sexual difficulties in the context of dementia is limited not only by the paucity of research prior to the NSHAP study but also by the question of reliability, given the participants’ cognitive challenges. Poor short-term memory of recent sexual experiences, a tendency to minimize concerns, and loss of insight can limit accuracy. Inclusion of the partner would appear to be essential. Both partners being seen together and separately, as in this large study, would facilitate the most reliable data. Nevertheless, later stages of severe dementia preclude reliable data, which cannot be corroborated by that partner (e.g., the patient’s wanting or enjoyment of sex).

The relationship between cognition and sexuality

Studies prior to NSHAP found associations between cognition and sexuality. A study of 3060 men and 3773 women aged 50 to 89 completed word recall and number sequencing tests.[11] Men confirming sexual activity in the previous year showed better recall and sequencing than those who were not sexually active. For women, the same was true for word recall. The direction of causality remained unknown. A second publication showed that more frequent sexual activity predicted better performance on Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination total score and in the domains of fluency and visuospatial abilities.[12]

In both the second (2011) and third (2016) waves of NSHAP, both sexual and cognitive assessments were included in the in-home interviews and the questionnaires that couples completed in private. Cognitive function in 2011 did not predict sexual frequency or quality (i.e., how pleasurable sexual activity was) in 2016. Interestingly, for participants younger than 74 years of age, the quality of their sexual lives related to better cognitive function 5 years later. For older participants, sexual frequency was found to be associated with better cognitive function 5 years later.[13] It is unclear why this difference exists. Possibly only those couples for whom sex is very pleasurable continue after age 74, and thus frequency may be the only remaining variable.

Another study collected baseline intimacy and sexuality survey data from 155 cognitively intact, married older adults. This cohort was followed for 10 years to evaluate any association between sexuality and future cognitive status. Over the 10-year study period, 33.5% of individuals developed cognitive impairment. Those with greater sexual satisfaction at baseline were less likely to develop mild cognitive impairment or dementia over the study period, irrespective of the romantic relationship, social supports, emotional intimacy, or beliefs about sexuality.[14]

Data from the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project found that men with declining sexual frequency and erectile dysfunction experienced greater decline in Mini-Mental State Examination scores over 5 years of follow-up.[15] This association remained even when potential confounds, including age, BMI, comorbidity, number of medications, smoking, depression, self-rated health, and hormone levels, were accounted for in statistical analyses.

Complexities of sexual dysfunction in dementia

The brain areas involved in sexual response have been clarified by functional imaging over the past 2 decades.[16] The areas include those of the “sexual interest network,” their activation necessary to recognize and attend to sexual stimuli, allow sexual imagery, and motivate or inhibit subsequent behavior. Then follows the activation of some and de-activation of other areas for arousal and other areas for orgasm, all followed by very different areas of activity and suppression, reflecting the postorgasmic state. However, as researchers have recently noted, networks serving higher-order cognition and memory are also intrinsically involved in partnered sexual experiences.[17] These include the ability to feel pleasure, learn more rewarding sexual acts, have empathy with the partner’s emotions, manage one’s fears of rejection or embarrassment, and allow the disinhibition needed for arousal and sexual activity. These circuits are all potentially compromised by dementia. Indeed, using brain imaging to quantify changes in sexual behavior in behavioral-variant frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease, researchers’ findings suggested the involvement of specific neural circuits that demonstrated an interplay between circuits involving reward, empathy, and emotional processing, as well as those associated with autonomic function.[18] Given that interruption of neural circuits is not limited to those directly involved in sexual arousal, the complexities of sexual dysfunction from dementia are likely not only different from persons without cognitive challenges but also highly unstable as the disease worsens.

We have little information on these dementia-related sexual dysfunctions, though the NSHAP study has a number of interesting findings. Forty-five percent of men and 73% of women living with dementia disliked “genital sexual touching.” However, they maintained a sexual focus on intercourse and reported slightly lower prevalence of erectile dysfunction and female orgasm difficulties. Manual genital stimulation is typically involved for women to orgasm, and older men will usually need manual stimulation in addition to mental sexual arousal to experience erections sufficiently firm to allow intercourse, which makes this finding somewhat perplexing and worthy of further exploration. Also of note is the low frequency of sexual avoidance shown by women living with dementia [Table 1].

Why are physicians hesitant to include sexual inquiry during a systems review?

Sexual history taking has been identified as an often overlooked domain of the clinical interview.[19] Potential reasons for excluding sexual inquiry include misgivings of inappropriateness, uncertainty about how to broach the subject, a mistaken belief that sex would no longer be important, and a fear of opening a Pandora’s box, given a lack of experience in addressing sexual concerns, competing clinical priorities in a time-constrained setting, or lack of options for referral of complicated cases.

Why is sexual inquiry necessary in this population?

Sexual activity remains important for those with cognitive decline. Beyond the value of sex to facilitate emotional intimacy and physical pleasure, recent research suggests that sexual frequency and satisfaction may positively influence future cognition.[13] As outlined above, sexual satisfaction was positively correlated with cognition 5 years later in participants 66 to 74 years of age. In those aged 75 to 85, sexual frequency was positively correlated with cognition 5 years later.[13]

Further, a 10-year cohort study revealed that sexual satisfaction was associated with decreased risk of transitioning from normal cognition to mild cognitive impairment or dementia.[14] Thus, difficulties with sexual function may be a novel modifiable risk factor for development of cognitive impairment.

Research supports the notion that patients want their physician to ask about sexual problems and that they are much more likely to engage if the physician initiates this discussion.[20]

When and how should physicians inquire about sexual function?

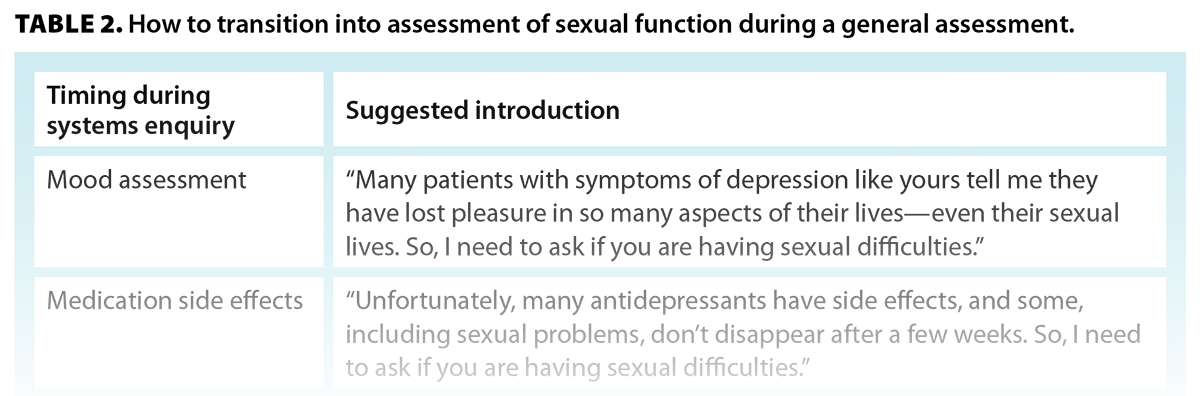

During a general assessment, appropriate opportunities for sexual inquiry include assessments of mood or cognition. An introductory sentence has been shown to increase patients’ comfort with confirming that they have a problem [Table 2].[21] These introductory sentences validate and normalize the difficulty and are known to facilitate disclosure.[21] Patients can find it reassuring to know that their symptoms are logical and experienced by others in their situation.

What can physicians do to address sexual problems?

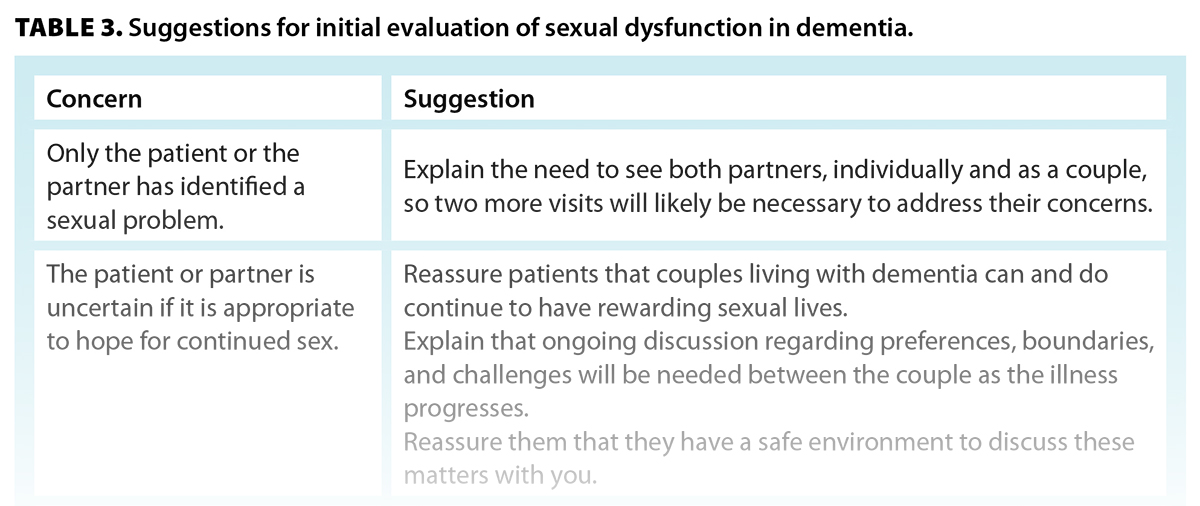

Physicians may be able to offer solutions to address an elicited sexual concern at a future visit [Table 3]. If this is not possible, the couple may welcome a referral to the BC Centre for Sexual Medicine, where such referrals are currently given priority. A referral form is available at www.vch.ca/sites/default/files/2024-12/BCCSM-Referral-Dec-2024.pdf. The centre’s fax number is 778 504-9746.

Conclusions

For patients with dementia, degeneration in the areas of the brain involved in higher-order cognitive networks involved in partnered sexual activity may compound sexual dysfunctions common to older persons without cognitive loss. However, research identifies strong sexual resilience in many couples living with dementia, but minimal physician intervention. Importantly, ongoing sexual activity may foster cognition as well as benefit general health and happiness. It is important to no longer neglect this aspect of patients’ health. In BC, consultation for sexual dysfunction in this population is currently available in a timely manner.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Albert SC, Martinelli JE, Costa Pessoa MS. Couples living with Alzheimer’s disease talk about sex and intimacy: A phenomenological qualitative study. Dementia (London) 2023;22:390-404. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012221149759.

2. Lindau ST, Dale W, Feldmeth G, et al. Sexuality and cognitive status: A U.S. nationally representative study of home‐dwelling older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1902-1910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15511.

3. D’cruz M, Andrade C, Rao TSS. The expression of intimacy and sexuality in persons with dementia. J Psychosexual Health 2020;2:215-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2631831820972859.

4. Meston CM, Buss DM. Why humans have sex. Arch Sex Behav 2007;36:477-507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9175-2.

5. Lima Nogueira MM, Brasil D, Barroso de Sousa MF, et al. Satisfação sexual na demência. Arch Clin Psychiatry (São Paulo). 2013;40:77-80. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832013000200005.

6. Bronner G, Aharon-Peretz J, Hassin-Baer S. Sexuality in patients with Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol 2015:130;297-323. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00017-1.

7. Ballard CG, Solis M, Gahir M, et al. Sexual relationships in married dementia sufferers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;12:447-451.

8. Waite LJ, Iveniuk J, Kotwal A. Takes two to tango: Cognitive impairment and sexual activity in older individuals and dyads. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2022;77:992-1003. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbab158.

9. Basson R. Human sex-response cycles. J Sex Marital Ther 2001;27:33-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926230152035831.

10. Basson R, Weijmar Schultz W. Sexual sequelae of general medical disorders. Lancet 2007;369(9559):409-424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60197-4.

11. Wright H, Jenks RA. Sex on the brain! Associations between sexual activity and cognitive function in older age. Age Ageing 2016;45:313-317. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv197.

12. Wright H, Jenks RA, Demeyere N. Frequent sexual activity predicts specific cognitive abilities in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2019;74:47-51. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx065.

13. Shen S, Liu H. Is sex good for your brain? A national longitudinal study on sexuality and cognitive function among older adults in the United States. J Sex Res 2023;60:1345-1355. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2238257.

14. Smith AG, Bardach SH, Barber JM, et al. Associations of future cognitive decline with sexual satisfaction among married older adults. Clin Gerontol 2021;44:345-353. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1887420.

15. Hsu B, Hirani V, Waite LM, et al. Temporal associations between sexual function and cognitive function in community-dwelling older men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age Ageing 2018;47:900-904. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy088.

16. Ruesink GB, Georgiadis JR. Brain imaging of human sexual response: Recent developments and future directions. Curr Sex Health Rep 2017;9:183-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0123-4.

17. Nordvig AS, Goldberg DJ, Huey ED, Miller BL. The cognitive aspects of sexual intimacy in dementia patients: A neurophysiological review. Neurocase 2019;25:66-74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13554794.2019.1603311.

18. Ahmed RM, Hodges JR, Piguet O. Behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia: Recent advances in the diagnosis and understanding of the disorder. Adv Exp Med Biol 2021;1281:1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51140-1_1.

19. Virgolino A, Roxo LF, Alarcão V. Facilitators and barriers in sexual history taking. In: The textbook of clinical sexual medicine. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. pp. 53-78. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-52539-6_5.

20. Sadovsky R, Nusbaum M. Reviews: Sexual health inquiry and support is a primary care priority. J Sex Med 2006;3:3-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00193.x.

21. Sadovsky R, Alam W, Enecilla M, et al. Sexual problems among a specific population of minority women aged 40-80 years attending a primary care practice. J Sex Med 2006;3:795-803. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00288.x.

Dr Rosetti is a sexual medicine physician and academic co-head at the BC Centre for Sexual Medicine. Dr Basson is a clinical professor emerita at the University of British Columbia and past director of the BC Centre for Sexual Medicine.

Corresponding author: Dr Leah Rosetti, leah.natalie.rosetti@gmail.com.