Original Research

Supporting the stillbirth journey at BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre

ABSTRACT

Background: Nearly all stillbirths in Canada occur in hospitals—a setting that can either support or exacerbate what is often a traumatic experience. People with lived experience of stillbirth face psychological challenges, barriers to seeking support, and stigma; therefore, patient engagement is critical to optimizing stillbirth care.

Methods: We conducted a quality improvement project through a human-centred design approach to understand the hospital stillbirth experience and co-design a vision for improved stillbirth care at BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. We engaged 30 bereaved parents in two workshops and used design methods to promote reflection and gather insights about their experiences.

Results: Four key themes emerged via reflexive thematic analysis, which highlighted bereaved parents’ desire for stillbirth-specific care, care that honors the baby and recognizes the parents, provision of accommodating spaces, and sharing of information with care.

Conclusions: The hospital setting, designed primarily for live deliveries, can contribute to the suffering of bereaved parents of stillborn babies.

The hospital setting, designed primarily for the delivery of live infants, can profoundly shape the experience and memory of those who have a stillbirth in pregnancy.

Background

In Canada, stillbirth is defined as the birth of a fetus or baby with no signs of life at 20 weeks or more gestational age or birth weight of 500 grams or more.[1] In 2022, 3169 people experienced a stillbirth in Canada, of which 567 took place in BC.[2-4] Nearly all stillbirths occur in a hospital setting,[5] where the stillbirth journey from diagnosis to discharge has been described as erratic, confusing, and heartbreaking.[6]

Stillbirth is a significant public health concern that can have profound and lasting impacts on those who experience the loss and their loved ones.[7] People can experience a wide range of intense emotions, including shock, anger, shame, and profound grief following stillbirth.[7,8] Individuals’ emotional responses vary considerably and may be influenced by factors such as social support, previous experiences with pregnancy and childbirth, and the specific circumstances in which the pregnancy or loss took place.[9-13] People who experience such a loss have, on average, higher rates of anxiety, depression, substance use, and posttraumatic stress disorder than those who have a live birth.[11,13-16] These psychological challenges may persist into subsequent pregnancies and affect overall well-being and quality of life.[17] Following a stillbirth, close family members, including partners and grandparents, may also experience significant grief and increased mental health concerns.[7,10,18,19] Stigma affects the social identities of those who view themselves as bereaved parents; thus, identity repair is crucial to stillbirth recovery.[20] In this article, we use the term “bereaved parents” to reflect the preferred language of our study participants, all of whom regarded the stillbirth as the loss of a baby and identified themselves as parents. We acknowledge that this term does not reflect the realities of all people who experience stillbirth. Due to stigma, bereaved parents and loved ones experience guilt, isolation, and alienation.[21,22] Partners often face the erasure of their status as grieving parents and may find it more challenging to seek support than birth parents.[7,10,23]

Given that hospital care is a common component of the stillbirth journey, quality improvement in this setting is an institutional responsibility. Implementing empathy-driven practices within the hospital can modulate the psychological distress and stigma experienced by people and cultivate a supportive stillbirth journey.[6,12,20,24,25] Given the multiple ways in which people experience their stillbirth, it is essential to engage people with lived experience in quality improvement–based initiatives.[26,27] Amplifying individuals’ perspectives promotes equity, mutual respect, and shared decision making, all of which are integral to high-quality care.[28]

As a provincial referral center, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre has the highest volume of stillbirths in BC. Of the 561 stillbirths recorded in BC in 2022, 333 occurred at BC Women’s; 9% were spontaneous.[3,4] Because patient and health care provider feedback indicated that care could be improved, we conducted a study to understand the hospital stillbirth journey of people with lived experience and to co-create options for improving the experience.

Methods

Our quality improvement project employed a human-centred design approach, which puts the needs of service users at the centre of the design process when addressing complex problems.[29,30] To ensure people with lived experience of stillbirth were integrated into the study as decision-makers, co-design methods of engagement—participatory approaches to designing with rather than for people—were used throughout.[30,31] This is in contrast to traditional user-centred design methods, which often engage individuals through observation and interview-based approaches.[32] By bringing together people with lived experience, designers, and health care professionals to learn from and work alongside each other, the voices of those most directly impacted can be elevated to inform direct outcomes.[31]

Given that stillbirth care is a sensitive topic and the experience of stillbirth can be traumatic, we used a trauma-informed approach that prioritized comfort, trust, transparency, safety, and support.[33] This took the form of shared decision making regarding the design of the project’s visual identity [Figure 1], a relational approach to recruitment, cultural and psychological support during the workshops, co-facilitation of workshops, co-analysis of information gathered, and peer support throughout the project.

For this three-phase project, we assembled an 18-person core design team, including two people with lived experience of stillbirth, learners from design and medicine, and members of the BC Women’s Population Health Promotion team and the Emily Carr University of Art + Design’s Health Design Lab (see the acknowledgments). The first phase involved convening the core design team and co-learning about stillbirth. The second phase included the engagement of people with lived experience in two co-design workshops. The final phase consisted of data analysis and knowledge sharing with BC Women’s clinical and operational staff, bereaved parents, and participants at a national conference. The project was approved by the Provincial Health Services Authority’s Information Access and Privacy Office.

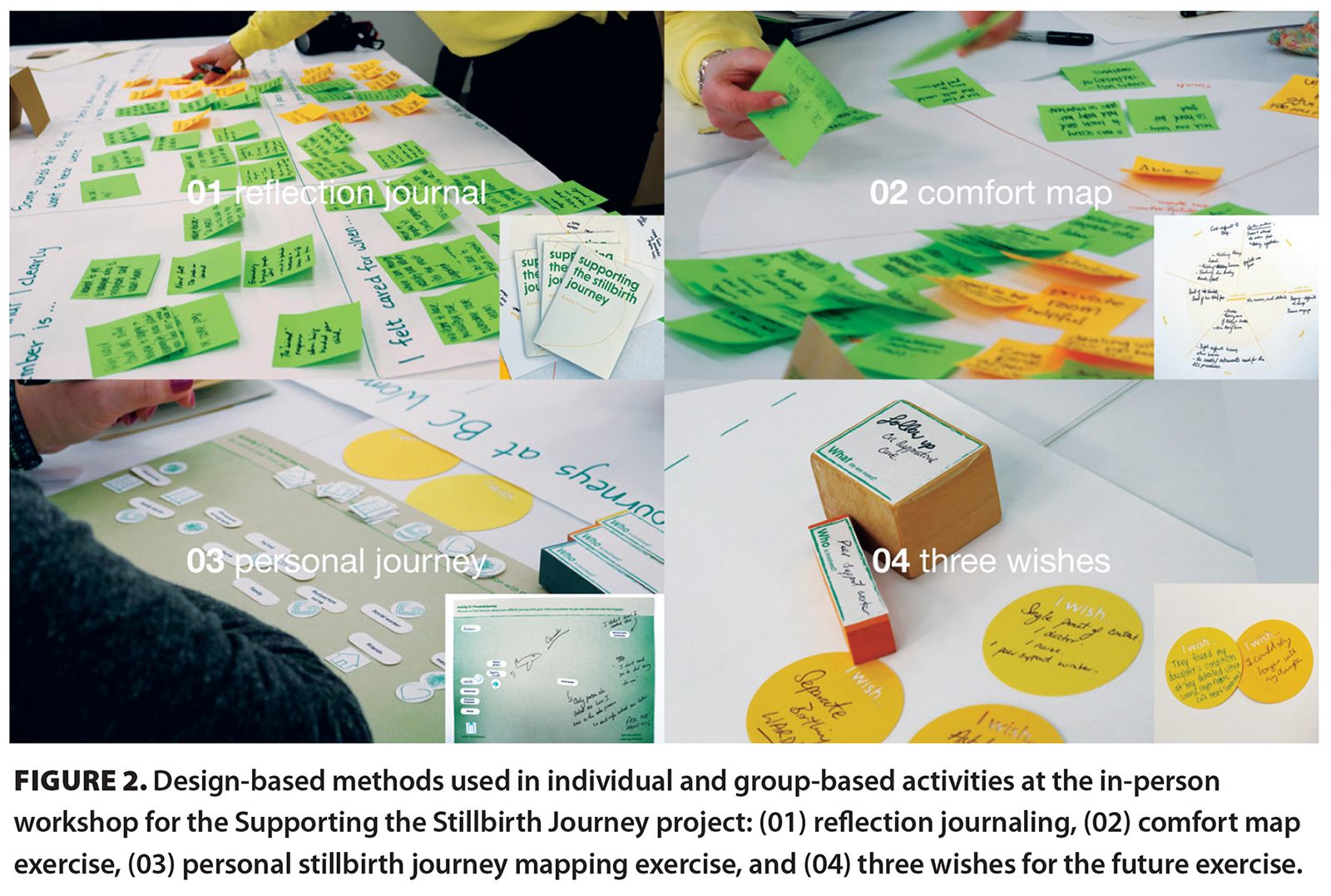

Building on our team’s existing relationships with community partners across BC, such as the Midwives Association of BC, the Aboriginal Mother Centre Society, and the Butterfly Run, we sent an electronic invitation to approximately 1000 people. We collected data from bereaved parents via two co-design workshops (one in person and one virtual) and a demographic survey. The virtual workshop was offered to gather perspectives from across BC. Completion of the demographic survey was optional. Individuals were recruited via purposive and snowball sampling methods across the provincial health authorities. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be BC residents and had to have experienced a stillbirth in BC. Individuals were compensated at a rate of $20 per hour for their engagement, provided a list of community resources, and connected with a community of bereaved parents. The workshops engaged people in four individual and group-based activities: (1) reflection journaling, (2) a comfort map, (3) a personal stillbirth journey map, and (4) three wishes for a future stillbirth-specific care program [Figure 2].

Key insights from the workshops were synthesized from participants’ written responses on activity sheets and through note-taking of group conversations using reflexive thematic analysis. This method emphasizes the reflexive and iterative process of identifying and interpreting themes and involves researchers acknowledging and reflecting on their values, experiences, interests, and social locations to inform the analysis process and produce key themes.[34,35] Pairs of reviewers from BC Women’s and the Health Design Lab analyzed data to ensure the information was interpreted using two different lenses.

Results

We engaged 30 bereaved parents: 27 birth parents and three support people. Twelve bereaved parents attended the in-person workshop; 18 attended the online workshop. The demographic survey was completed by 25 birth parents and one support person. With the exception of one participant, the individuals in our sample experienced their stillbirth(s) in the past 10 years and were 24 to 41 years old at the time of their loss. Of 25 respondents who completed the demographic survey, 15 identified as White and 10 identified as multi-ethnic, Chinese, Filipino, or Indigenous. The in-person workshop in Vancouver attracted a higher proportion of participants who identified as non-White (70%, versus 20% in the virtual session). All birth parents identified as female, and all support people identified as male. Thirteen birth parents reported a spontaneous stillbirth, 9 experienced the loss in the context of a termination, and 3 presented with preterm premature rupture of membranes/abruption and delivered a stillborn infant. Sixteen bereaved parents experienced their stillbirth at BC Women’s; the remainder experienced theirs at other sites within the Vancouver Coastal Health, Fraser Health, Interior Health, and Vancouver Island Health Authorities. All bereaved parents had delivered their stillbirths within a maternity setting via vaginal delivery or cesarean section; none had a surgical procedure for evacuation.

The reflexive thematic analysis generated four key themes: stillbirth-specific care, honoring the baby and recognizing the parents, accommodating spaces, and sharing information with care. All quotations came directly from workshop participants but were not collected with attribution.

Stillbirth-specific care

Bereaved parents emphasized the need for comprehensive stillbirth-specific care delivered by a collaborative team equipped with the knowledge and skills to provide empathetic, sensitive, and appropriate information. They wished to avoid a medicalized atmosphere and identified the distress of having to recount their story to new health care providers with each shift change. They also expressed the need for care to be appropriate to one’s stage of bereavement. Bereaved parents valued genuine connection, including human touch, feeling listened to, and continuity in their care team. They had differing views on the appropriateness of health care providers expressing emotion during the stillbirth journey. While some found any display of emotions by health care providers distressing and burdensome, others interpreted this as empathetic. Although clinical skills were valued, other aspects of care that were appreciated included accessible language, access to religious and spiritual services, and continuity of care.

Many bereaved parents valued having a dedicated patient navigator to support them through their hospital stay; several referenced social workers as fulfilling this role. However, some parents reported their preference for a navigator with more knowledge about birthing in the setting of loss, such as a bereavement doula.

Some aspects of care specific to the stillbirth journey sparked frustration and dissatisfaction for some bereaved parents: “[My stillbirth] was not being treated with urgency. I’m frustrated with how the autopsy process . . . [was] dealt with. [I was] frustrated with the [obstetrician] . . . for the lack of support and interpretation of the genetics report.”

Bereaved parents emphasized the importance of health care providers in giving them options, flexibility, and time to make informed decisions at each step of the stillbirth journey to allow them to feel a sense of autonomy and choice. Some felt rushed to decide whether to terminate their pregnancy after receiving a prenatal diagnosis. One parent expressed dissatisfaction with being hurried to decide whether to pursue an autopsy. Others felt the weight of the paperwork, funeral arrangements, and other decisions that had to be made in short succession: “[I felt a] lack of empathy from the social worker; you have to pick a funeral home before you leave the room.”

Many bereaved parents emphasized the desire to create a network of support across BC to help reduce isolation during the stillbirth journey. The types of networks envisioned varied. Most commonly, members included partners, family members, friends, spiritual counselors, health care providers, and peer navigators. The proposed role of health care providers in these networks was to provide holistic support, including care for patients’ mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical health. Bereaved parents also highlighted a desire for support from peers who had similar lived experiences of stillbirth so they could feel understood and validated. Peer support workers were described as potential advocates and valuable sources of advice. One parent stated, “[There is a need to] create a network of [parents] who have been through it. Put out a call when someone enters the hospital so the parents can be greeted and looked after, after the stillbirth.”

Another parent described having both instrumental and emotional support in activities of daily living from their support circle: “My people held space for me, even in silence. They fed me and made sure I bathed [and] brushed my teeth.”

Finally, many parents shared their desire for improved guidance regarding self-care practices, including care for one’s body and body image during and after stillbirth. Specifically, some revealed the lack of information they received on how to manage their childbirth afterpains and physical recovery. Several indicated that they had not been informed about the likelihood of lactating after stillbirth, or the options for suppressing lactation or donating their breastmilk: “Coming from [the] Okanagan, I wasn’t provided with much information. When the milk started to come . . . I didn’t know where to look. I would [have liked] to know about my options . . . from a health care professional. That piece was missing.”

Honoring the baby and recognizing the parents

All bereaved parents emphasized the value of engaging in activities that honored their baby and taking moments to validate their role as parents, such as singing to the baby, casting the baby’s handprints and/or footprints, and taking photographs. Parents felt that mementos helped them process their grief and remember their baby. Some individuals said that saving these mementos in a memory box felt like an act of care for themselves and their baby. One parent said, “I found out a lot from the social worker. She told me about ‘Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep’ for digital photos, which really helped me to have quality pictures. . . . Professional photography was good at how to pose with the baby, and I am holding the baby instead of the nurse taking the baby away to take pictures . . . by themselves. I treasure the photos with my baby, holding my baby.”

Bereaved parents stated the desire to have health care providers treat them like parents and honor their baby. Individuals who experienced health care providers holding or caring for the baby or using their baby’s name expressed feeling respected and safe. Many participants did not feel that health care providers sufficiently acknowledged their role as parents and thus felt excluded from decision-making processes. For many, the perceived erasure of their status as parents was hurtful: “[I would have] appreciated being treated like a mom—being asked what his name [and] weight [were]. It would have helped me to have felt cared for and treated like a mom.”

Several parents expressed dissatisfaction with how health care providers treated their stillborn baby. Individuals felt the care their baby received was dehumanizing and sterile. They conveyed their wishes for health care providers to have honored their stillborn baby by treating their bodies with respect. One birth parent who delivered twins—one of which was stillborn and the other of which survived—shared how they felt health care providers neglected their stillborn child in favor of their live-born child, making them feel like the deceased baby was an “afterthought”: “[I] never got an acknowledgment from [the] physician in [the] room about [my] son who did not survive.”

Accommodating spaces

Bereaved parents highlighted the importance of health care providers providing mindful care to prevent unnecessary exposure to potentially triggering hospital settings that provoke increased anxiety and emotional pain. Ultrasounds were frequently described as triggering events. The absence of a fetal heartbeat was a sensory experience that many remembered vividly. Additionally, one of the most distressing aspects was the prolonged wait time between being informed about the absence of a heartbeat and speaking with a physician.

Bereaved parents wished for spaces that could meet their needs for comfort and privacy. Steps taken to increase privacy and sensitivity, such as marking the door with a butterfly to signify a stillbirth, were often noticed and valued. Many expressed discomfort with unfamiliar health care providers entering their room unannounced without acknowledging the family. Additionally, several spoke about the experience of hearing live babies crying in adjacent rooms following their stillbirth. One parent stated, “The most memorable sound is the silence—so hearing all the other sounds of live babies is emotional and difficult to be around.”

Sharing information with care

Bereaved parents stressed that information be shared using sensitive language and with considerate timing. Most parents objected to terms such as “fetus,” “abortion,” and “incompatible with life,” which were described as hurtful and dehumanizing.

Several parents stated that health care providers had given them unsolicited advice that, while well intentioned, felt belittling and did not contribute to their healing. Language used by health care providers with the intention of conveying hope was often perceived as paternalistic, inappropriate, and invalidating. Examples included parents being told that “everything happens for a reason” or that they were “still young enough” to have another child.

Bereaved parents shared frustration that they were not provided with comprehensive, accessible resources on stillbirth. In general, having resources available in a variety of formats (e.g., digital, written) was preferred. Some said that attempts by health care providers to “sugarcoat” their situation interfered with the clarity of information shared. One parent commented “[I] did not need them to coddle me throughout the journey.”

Discussion

Stillbirth affects approximately 3000 families in Canada annually, and most stillbirths occur in hospital.[2,4] Our study focused on identifying opportunities for improving stillbirth care at BC Women’s.

Bereaved parents shared their vision of an integrated, stillbirth-specific system of care, provided by teams with appropriate knowledge and skill, and a network of support. Health care providers must possess not only clinical skills but also the nonclinical acumen to convey empathy without burdening patients. Stillbirth-specific care should include guidance on spiritual and/or religious support and postpartum self-care (e.g., breast milk donation or lactation suppression) and be coordinated by a dedicated patient navigator. Care must honor autonomy and be appropriate to individuals’ stage of bereavement. Our initiative emphasizes the need to respect parents’ pace when making decisions. Parents expressed feeling rushed to make choices, even when they had not fully processed all the information provided to them.

Bereaved parents wished for more of a focus on memorializing their baby through memory making, including singing to the baby, taking photographs, casting handprints or footprints, and making memory boxes. Those who did not have the opportunity to take part in such memory making expressed regret, having wished that others had guided them to do so. Health care providers were appreciated when they helped facilitate these experiences, both affirming the bereaved parents’ identity as parents and honoring their baby.

Hospital spaces should be intentionally designed to minimize triggering situations and enhance comfort during the stillbirth journey. While ultrasounds are a necessary diagnostic step in stillbirth care, they were a significant source of distress. Several parents endured long wait periods without confirmation of stillbirth and discussion of subsequent steps. Bereaved parents highlighted the striking contrast between the silence surrounding their stillbirth experience and the sounds of crying babies from neighboring rooms. This underscores the need to re-evaluate the design of birthing wards and room assignments. While predicting stillbirth may not always be possible, thoughtful consideration could be given to assigning the birth parent to a room situated away from delivery rooms or equipped with enhanced soundproofing. Parents emphasized the significance of privacy and expressed appreciation for health care providers who respected their space by placing a butterfly on their door.

The interactions with health care providers had a lasting impact on parents’ memories, even years after a stillbirth. The importance of health care providers delivering thoughtful and consistent communication, along with accessible resources in various formats, was highlighted. Parents said that certain words, such as “fetus,” “abortion,” and “incompatible with life,” invalidated their experiences and intensified their pain during the stillbirth journey. Health care providers should encourage parents to express their preferred language when discussing their stillbirth and follow their lead in choosing compassionate terminology. Most parents agreed that they did not want to be “coddled” but desired genuine expressions of empathy. In light of these findings, it may be valuable to enhance training specific to stillbirth care, such as more mindful approaches to diagnostic procedures and information sharing. Training should be based on a standardized protocol for optimizing patient privacy and support during the hospital stillbirth experience, with the goal of fostering positive interactions between health care providers and people who experience a stillbirth.

Study limitations

This study was limited by a small sample size and homogeneity. All participants who chose to attend the workshops viewed themselves as bereaved parents and none had experienced the stillbirth via surgical dilation and evacuation. Given these limitations, the aim of this quality improvement initiative was not to represent the diversity of stillbirth experiences across BC, but rather to serve as a starting point for ongoing efforts to optimize stillbirth care at BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre.

Conclusions

The hospital setting, designed primarily for the delivery of live infants, can profoundly shape the experience and memory of those who have a stillbirth in pregnancy.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

We thank the bereaved parents who participated in this project for sharing their stillbirth journeys and the Butterfly Run Vancouver for their support of the project. We thank the 18-member core design team. The following members of this team were involved in different capacities, across multiple stages of the project: Darci Rosalie (registered nurse on an Indigenous health team), Otilia Spantulescu (Health Design Lab coordinator), Olivia Bauer (clinical counselor), Jennifer Albon (perinatal nurse), Barbara Lucas (social worker), Frances Jones (provincial milk bank coordinator), and A.J. Murray (knowledge translation specialist). We are grateful for the support from the hospital’s Maternal/Newborn Program team, especially Dr Janet Lyons and Ms Anne Margaret Leigh.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Public Health Agency of Canada. Chapter 7: Loss and grief. In: Family-centred maternity and newborn care: National guidelines. 2018. Accessed 27 April 2023. www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/maternity-newborn-care-guidelines-chapter-7.html.

2. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0428-01. Live births and fetal deaths (stillbirths), by type of birth (single or multiple). 2022. Accessed 27 April 2023. www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310042801.

3. Perinatal Services BC. Database of stillbirth in British Columbia, 2022. Obtained through a data request.

4. BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. Discharge abstract database, 2018–2022. Obtained through a data request.

5. Statistics Canada. Live births and fetal deaths (stillbirths), by place of birth (hospital or non-hospital). 2022. Accessed 27 April 2023. www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310042901.

6. Downe S, Schmidt E, Kingdon C, Heazell AEP. Bereaved parents’ experience of stillbirth in UK hospitals: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002237.

7. Burden C, Bradley S, Storey C, et al. From grief, guilt pain and stigma to hope and pride—A systematic review and meta-analysis of mixed-method research of the psychosocial impact of stillbirth. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:9.

8. Cacciatore J. Psychological effects of stillbirth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;18:76-82.

9. Arocha P-R, Range LM. Events surrounding stillbirth and their effect on symptoms of depression among mothers. Death Stud 2021;45:573-577.

10. Cleaver H, Rose W, Young E, Veitch R. Parenting while grieving: The impact of baby loss. J Public Ment Health 2018;17:168-175.

11. Gold KJ, Leon I, Boggs ME, Sen A. Depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after perinatal loss in a population-based sample. J Womens Health 2016;25:263-269.

12. Smith LK, Dickens J, Bender Atik R, et al. Parents’ experiences of care following the loss of a baby at the margins between miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death: A UK qualitative study. BJOG 2020;127:868-874.

13. Lewkowitz AK, Rosenbloom JI, Keller M, et al. Association between stillbirth ≥ 23 weeks gestation and acute psychiatric illness within 1 year of delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:491.e1-491.e22.

14. Davoudian T, Gibbins K, Cirino NH. Perinatal loss: The impact on maternal mental health. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2021;76:223.

15. Hogue CJR, Parker CB, Willinger M, et al. The association of stillbirth with depressive symptoms 6–36 months post-delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2015;29:131-143.

16. Thomas S, Stephens L, Mills TA, et al. Measures of anxiety, depression and stress in the antenatal and perinatal period following a stillbirth or neonatal death: A multicentre cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:819.

17. Chojenta C, Harris S, Reilly N, et al. History of pregnancy loss increases the risk of mental health problems in subsequent pregnancies but not in the postpartum. PLoS One 2014;9:e95038.

18. Lockton J, Due C, Oxlad M. Love, listen and learn: Grandmothers’ experiences of grief following their child’s pregnancy loss. Women Birth 2020;33:401-407.

19. Murphy S, Jones KS. By the way knowledge: Grandparents, stillbirth and neonatal death. Hum Fertil 2014;17:210-213.

20. Brierley-Jones L, Crawley R, Lomax S, Ayers S. Stillbirth and stigma: The spoiling and repair of multiple social identities. Omega 2014;70:143-168.

21. Pollock D, Pearson E, Cooper M, et al. Voices of the unheard: A qualitative survey exploring bereaved parents experiences of stillbirth stigma. Women Birth 2020;33:165-174.

22. Gold KJ, Sen A, Leon I. Whose fault is it anyway? Guilt, blame, and death attribution by mothers after stillbirth or infant death. Illn Crises Loss 2018;26:40-57.

23. Riggs DW, Due C, Tape N. Australian heterosexual men’s experiences of pregnancy loss: The relationships between grief, psychological distress, stigma, help-seeking, and support. Omega 2021;82:409-423.

24. Ellis A, Chebsey C, Storey C, et al. Systematic review to understand and improve care after stillbirth: A review of parents’ and healthcare professionals’ experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:16.

25. Watson J, Simmonds A, La Fontaine M, Fockler ME. Pregnancy and infant loss: A survey of families’ experiences in Ontario Canada. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019;19:129.

26. Dudley DJ. Stillbirth: Balancing patient preferences with clinical evidence. BJOG 2018;125:171.

27. Kelley MC, Trinidad SB. Silent loss and the clinical encounter: Parents’ and physicians’ experiences of stillbirth—A qualitative analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:137.

28. Vahdat S, Hamzehgardeshi L, Hessam S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Patient involvement in health care decision making: A review. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014;16:e12454.

29. Melles M, Albayrak A, Goossens R. Innovating health care: Key characteristics of human-centered design. Int J Qual Health Care 2021;33(Suppl 1):37-44.

30. LUMA Institute. Innovating for people: Handbook of human-centered design methods. Pittsburgh, PA: LUMA Institute LLC; 2012.

31. McKercher KA. Beyond sticky notes: Doing co-design for real: Mindsets, methods and movements. Cammeraygal Country, Australia: Inscope Books; 2020.

32. Sanders EBN, Stappers PJ. Convivial toolbox: Generative research for the front end of design. Amsterdam: Bis Publishers; 2012.

33. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014.

34. Terry G, Hayfield N. Reflexive thematic analysis. In: Handbook of qualitative research in education. 2nd ed. Ward M, Delamont S, editors. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2020. pp. 430-441.

35. Braun V, Clarke V. (Mis)conceptualising themes, thematic analysis, and other problems with Fugard and Potts’ (2015) sample-size tool for thematic analysis. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2016;19:739-743.

Mr Gill is a student in the MD undergraduate program, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, and a FLEX project student with Population Health Promotion, BC Women’s Hospital and Health Centre. Ms Kreim is a student in the MD undergraduate program, Faculty of Medicine, UBC, and a FLEX project student with Population Health Promotion, BC Women’s. Dr Pederson is a senior director with Population Health Promotion, BC Women’s, and an investigator at the Women’s Health Research Institute. Ms Sullivan is a project manager with Population Health Promotion, BC Women’s. Ms Bashir and Ms Goldet are design research assistants at the Health Design Lab, Emily Carr University of Art + Design. Ms Mah is a clinical nurse educator in the Maternal Newborn Program at BC Women’s. Ms Kuznetsov and Ms Hiller are bereaved parents. Ms Beyzaei is a design lead and manager at the Health Design Lab, Emily Carr University. Dr Christoffersen-Deb is a medical director with Population Health Promotion, BC Women’s; an investigator at the Women’s Health Research Institute; and a clinical associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC.

Mr Gill and Ms Kreim contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript.

Ms Beyzaei and Dr Christoffersen-Deb contributed equally to the preparation of this manuscript.

Corresponding author: Dr Astrid Christoffersen-Deb, astrid.christoffersen@cw.bc.ca.