I must admit that I’m quite weary of “how to be…” articles. So it was with some trepidation that I began to read the recent BCMJ article by Gordon J.D. Cochrane, “Physicians and their primary relationships: How to be successful in both personal and professional realms.”

According to the author, the need for this advice exists because physicians tend to develop emotional self-protection in their work. Valuable as that is at work, if carried into relationships at home it may block the intimacy and openness that is central to a life-enhancing relationship. The article made me think about my life.

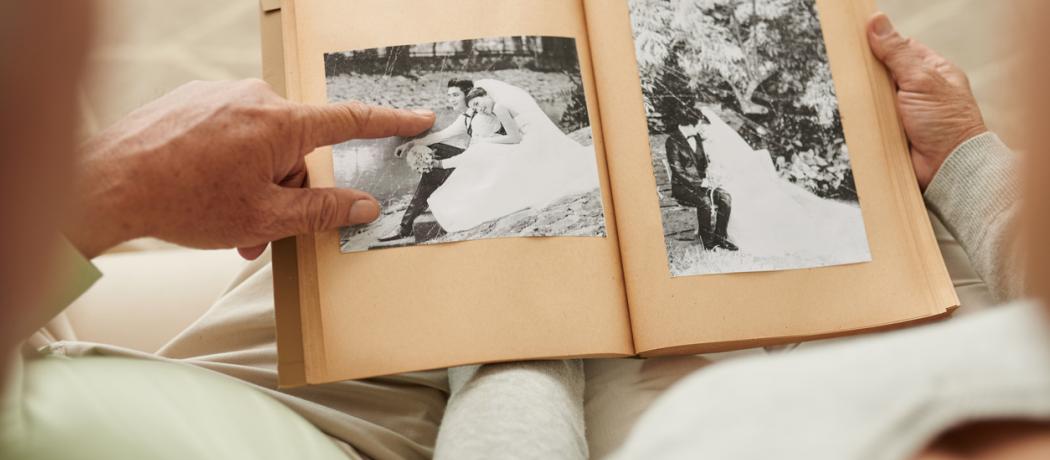

I remember how deeply in love I was while in medical school and during my internship. While seemingly always holding a retractor during my surgical rotation, my mind was on her and not on what I was doing. Things changed when I entered general practice. In the 1950s and early ’60s there were no pagers, there was no emergency department back-up, there was just a full waiting room in the office, relentless house calls, nights spent in the hospital doing maternity work, worries about doing the right things—it was all-consuming, full-time work. I had my wife and I loved her with all my heart but I found myself also married to my work. Even when we went on holidays I spent the first few days worrying how my last tonsillectomy patient was doing (in those days we did a lot of tonsillectomies).

It didn’t occur to me that I let her down. I felt that she was proud of my busy life, without resentment, and supported my preoccupation with medicine. She took the children to school in good spirits; she was the lead planner and fully involved with building our house, furnishing it, and doing the garden; she even did volunteer work with other doctors’ wives.

When I moved into academic life in the late 1960s I was under different pressures, but I worked with the same intense commitment. She missed her connections to the doctors’ wives but developed new friends in her favorite sport, tennis. Our children grew up and went their own nice ways. Some time ago I asked my doctor son if he missed that I was not at his high school sport events; he said that he was just as happy that I didn’t hang around him during soccer games or whatever else he was occupied with in his youth.

If I had read the article in those days, I would have acknowledged that I was focused on my work, but I would not have thought that we needed any marital help in the areas listed in the article—love and trust, effective communication and problem solving, similar views and values, sexual intimacy, enthusiasm for life, and a sense of humor. These factors were identified as common in a long-term study of satisfying marriages of 57 families (not of physicians’ families) in the US.

It never occurred to me to check in on our relationship along these lines. Our values and views were similar without us trying, we lived a relatively quiet life, we didn’t have much in the way of problems to solve, and I didn’t see much difference in our lifestyle from that of our doctor friends. We specialized: I was a doctor and she was a doctor’s wife.

Then an important change occurred in my life, and specifically, in my view on “sexual intimacy,” as it was referred to and described in the article. From the mid-1970s on much of my academic and clinical work was focused on the sexual and reproductive health issues of men and women with spinal cord injuries. I came to realize very rapidly that a significant block in rehabilitation for many persons was that in our culture “sex,” as in “having sex,” equals sexual intercourse: other forms of mutually satisfying or desired genital or body stimulations or intimate caressing are thought of as “foreplay.” Coitus, as a singular destination, may be satisfying for many people, but without knowing, understanding, or even caring about the needs of one’s partner, the single-minded pursuit of that act is a significant cause of interpersonal distancing from each other and the cause of a list of sexual dysfunctions, communication difficulties, and a host of other problems. Intimacy in my marriage changed along the lines I learned about in my work and that led to ongoing “enthusiasm for life and a sense of humor,” as the article’s author would have put it, even as we were getting older and older.

The author of the article proposes that physicians seeking success in both their professional and personal relationships need to be the best physicians they can be when working, and the best partner when with his or her partner. This recommended switch back and forth seems to me easier said than done. Whatever is the best, or applicable to all, I don’t really know.

In my life a mutual effort of trying to be “as good as we can be at this stage of our life” and then being able to look back and say, we did good enough, is perhaps more rewarding and more natural and open to growth than symbolically putting on and taking off a white coat, like superman or superwoman changing their cloak when called upon.

Regardless, I say a loud thanks to my wife every day, even in her deep dementia, for living with me for 65 years.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.