In a recent issue of the Vancouver Sun’s weekend review, concerns were raised about who has access to the data emanating from our robotic gadgets. Specifically, the article focused on robot vacuum cleaners that are able to spot pet droppings, photograph them, and send text messages to report the findings to the vacuum’s owner—with potential privacy costs.

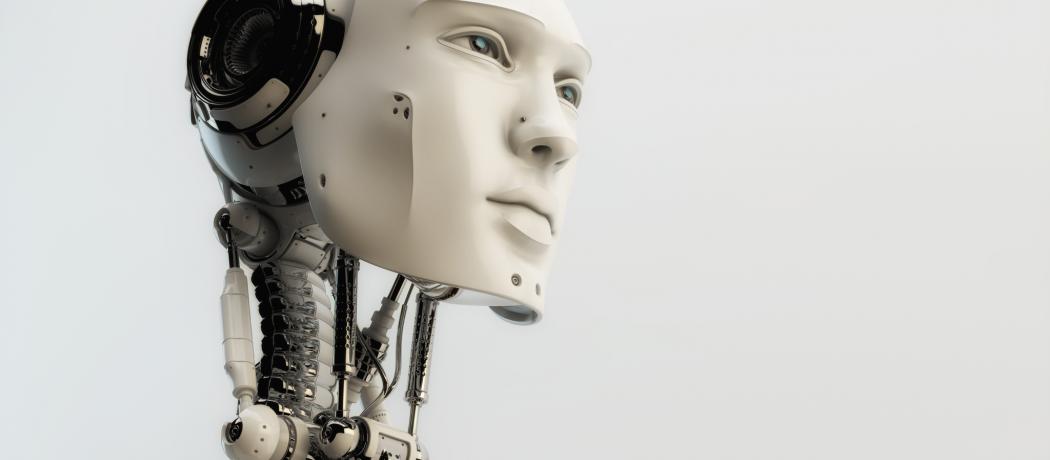

Robots are with us, in various forms, in our cars, homes, and hospitals. In a recent German romantic comedy, I’m Your Man, a handsome, charming, humanoid robot is introduced. The actor portraying the robot won a best-acting prize, and a thought crossed my mind: in the future, could a robot play the part of a human?

Humanoid robots have been the subject of several stories from famous fiction writer Isaac Asimov. In one, titled The Bicentennial Man, a household robot that has served a human family for several generations over 200 years applies to the judiciary to obtain a designation of being human. The machine claims that it knows everything about human behavior. Its request is refused, so it undergoes robot surgery to have a digestive tract, then lungs, then a beating artificial heart installed, and has its metallic surface covered with a human-like skin. The robot becomes a humanoid—in appearance, it is virtually a human.

Still, each subsequent application to be certified as human is rejected. Then the robot has an insight. The wiring in its humanoid body ensures virtual immortality, which is surely different from mortal humans, so it requests to have the wires cut in its robotic brain one by one. Just before the last connection is severed, the robot hands in yet another application to be accepted as a human. This time, as the robot is resting on its virtual deathbed, and just before its last wire is cut, the judiciary declares the now “mortal” 200-year-old humanoid robot a Bicentennial Man.

I was thinking of the story as I was leaving the long-term care home where now my beloved wife of 66 years is being cared for along with some 200 others human beings, many of whom are as unresponsive as she is—with some of their wires cut. I sighed, with tears in my eyes. The humanoid of the story is right: it is all living creatures’ destiny that our wires become loosened, torn, or cut, bit by bit from the time we are born until our last moments. What truly makes us mortal is facing up to this reality and dealing with all that happens to us and our loved ones over the course of our lives.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

Suggested reading

Asimov I. Robot series: The bicentennial man. Ballantine Books; 1976.

Brown D. What the robot vacuum saw. Vancouver Sun, 25 September 2021 Section B, front page.

Schomburg J, Schrader M, Braslavsky E. I’m your man. Cinematic production. 2021.

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.