In 165 AD an unknown condition (possibly small pox or measles) killed over 5 million people in Asia Minor, Egypt, Greece, and Italy. Roman soldiers brought the disease back to Rome and the Roman army itself was also decimated.

In 541 half the population of Europe was killed in the Plague of Justinian. This bubonic plague afflicted the Byzantine empire and Mediterranean port cities, and devastated Constantinople, where 5000 people died daily.

Between 1346 and 1353 another outbreak of bubonic plague, the Black Death, caused the deaths of an estimated 75 to 200 million people of Europe, Africa, and Asia. The disease is thought to have moved from continent to continent by way of merchant ships. Fleas living on rats onboard the ships were the likely breeding ground for the bacteria that devastated three continents.

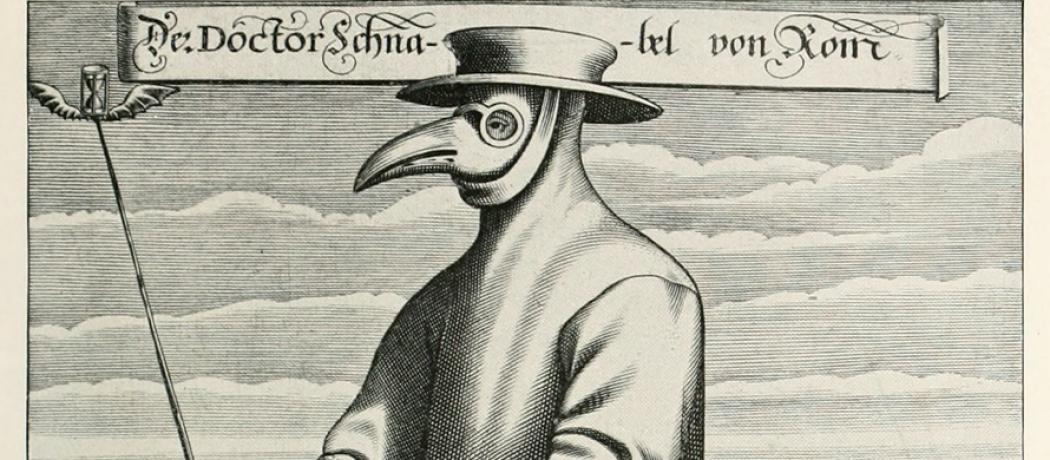

In the 17th and 18th centuries, threats of epidemic and pandemic diseases were blamed largely on citizens’ poor moral and spiritual condition. Prayer and pious behavior were thought to mediate the spread, but isolation or quarantine of the sick was also enforced in some European cities.

A cholera pandemic originating in India and lasting some 8 years between 1852 and 1860 spread through Asia, Europe, North America, and Africa, killing over a million people. In Great Britain 23 000 people died before John Snow identified contaminated water as the means of transmission for the disease.

By the late 18th century numerous isolation and quarantine measures were common in North American ports. Inoculation with material from small pox scabs became accepted as a means of containing small pox. Diseases were now seen less as a natural consequence of human conditions and more as events controllable through public actions.

In the 19th century human filth was identified as both the cause and the means of transmission of disease, and personal and community cleanliness became part of major social reforms. The health of the public became a societal goal. Rather specifically in Great Britain, remedies were based on assumptions that foul air and decomposition of waste causing diseases, so major public works were initiated, sewage removal systems were built, and boards of health were established. In the United States fingers were pointed at drunkenness and sloth, immorality and uncleanliness, and personal and community responsibilities for the environment were lauded for the sake of public health.

By the end of the 19th century the identification of bacteria and such interventions as immunization and water purification provided some means to control the spread of some of the diseases. Laboratory science and epidemiology emerged along with new ideas about causes of diseases and the social responsibility of public health agencies.

Now, virtually 200 years later, we are again facing a pandemic. This time it is a known viral agent that threatens the whole globe. In spite of unparalleled developments in most branches of medicine and advanced national public health measures, we are facing potential catastrophes, sickness, deaths, and economic disasters.

As to what to do about a pandemic, global warning systems, global institutions with funding and decision making powers, investments globally in research, improved detection and response systems, and holding realistic global training exercises are generally recognized as having great value toward preventing and fighting pandemics.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

Suggested reading

Gates B. Perspective: The next epidemic – lessons from Ebola. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1381-1384.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee for the Study of the Future of Public Health. The future of public health. Washington, DC: National Academic Press US; 1988. Accessed 27 February 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218224/

MPH Online. Outbreak: 10 of the worst pandemics in history. Accessed 27 February 2020. www.mphonline.org/worst-pandemics-in-history/

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.