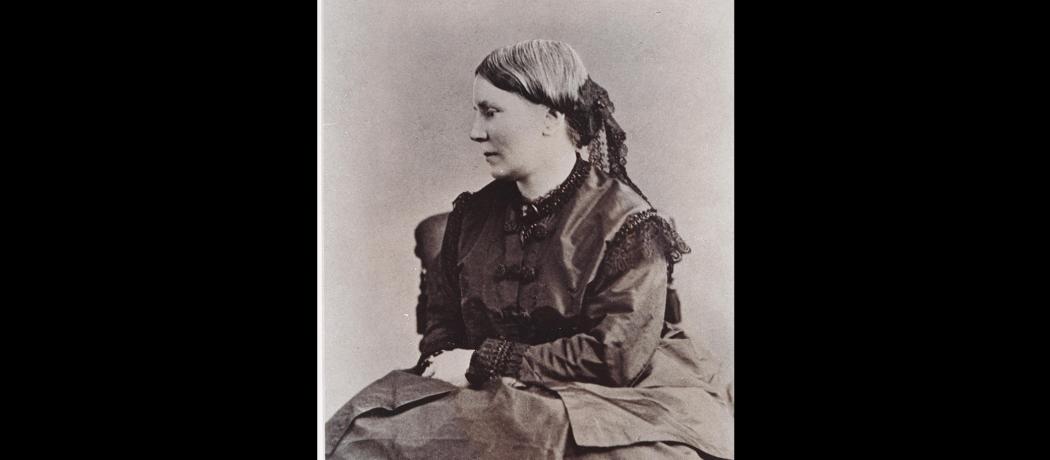

On 23 January 1849, Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman to receive a medical degree in the US. Dr Blackwell was born in England in 1821. When she was 11 years old, her parents and the family of four boys and five girls moved to America. Her father ensured that his daughters and sons were well educated.

In a book published in 1895, Elizabeth revealed that in her early 20s she, “hated everything connected with the body and could not bear the sight of a medical book.” Her mind was turned to medicine when a dying friend held her hand and wished that she had a “lady doctor” to look after her. A few years later, after enduring a heartbreaking end to a love relationship she decided to become a physician to “engross [her] thoughts. . . and prevent this sad wearing away of the heart.”

Physician friends in New York and Philadelphia tried to convince her that women would never be admitted to a medical school. Undaunted, she arranged to live in the home of a prominent physician as a children’s tutor so she could learn about medicine as a profession, use the medical library, and study Greek and Latin. She persevered and after numerous rejections she received acceptance to a small school, the Geneva Medical College in New York. Her diary reveals that, “[she] had not the slightest idea of the commotion created by [her] appearance as a medical student in the little town.”

Her attendance at anatomy lectures produced embarrassment in fellow students and the professor suggested that she stay away when reproductive anatomy was demonstrated. She did not. “A trying day,” she wrote in her diary. “Some of the students blushed, some were hysterically laughing.” In clinical sessions she had permission to observe patients and medical staff, but her presence was not well-received in the hospital ward and the young resident physicians refused to have anything to do with her.

At the graduation ceremony “there was a general stir and murmur and everybody turned to look.” She had won a gold medal. The dean declared his admiration for the first female MD, but in the print version of his speech he wrote that the “inconveniences of females attending to all lectures are so great that I will feel compelled to oppose such a practice.”

The Boston Medical Journal of 12 February 1849 condemned “the farce enacted at the Geneva Medical College.” The editor wrote, “I hope for the honor of humanity, that it will be the last.”

After graduation Elizabeth left for London and Paris where she received training in women’s and children’s diseases and in midwifery. She returned to New York City but she had few patients; she faced what she called “a blank wall of social and professional antagonism.” She gave up her dream to become a surgeon and her career moved in a different direction, promoting preventive medicine and creating opportunities for women in medical education.

In 1854, her younger sister, Emily, graduated from the Medical College of Western Reserve University after having been rejected by several other medical schools. Subsequently she studied in London, Paris, and Berlin. In 1857, Elizabeth, Emily, and a Polish immigrant, Dr Marie Zakrzewska, opened the New York Infirmary for Women and Children. Ten years later, they opened the doors of the Women’s Medical College with 15 students and nine faculty members.

In 1869 Elizabeth left New York to return to England where she founded the National Health Society with the motto, “Prevention is better than cure.” In 1874 she and Dr Sophia Jex-Blake and Dr Elizabeth Garret Anderson established the London School of Medicine for Women.

Elizabeth also published books and pamphlets about health and medicine and for years she was involved in reform movements including hygiene, medical education, preventive medicine, sanitation, family planning, and women’s suffrage.

Dr Elizabeth Blackwell died in 1910, at age 89, of complications secondary to a fall. Her legacy is monumental. She not only broke the barrier to women becoming physicians, she opened the doors wide for many more women to become doctors.

In my 1955 UBC medical school graduating class, 6.6% of the students were women. In this year’s graduating class at UBC and most other medical schools in Canada, close to 60% of the students will be women.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

Suggested reading

Blackwell E. Pioneer work in opening the medical profession to women. London, UK: Longmans, Green and Co.; 1895.

Britannica. Emily Blackwell, American physician and educatory. Accessed 23 January 2022. www.britannica.com/biography/Emily-Blackwell.

Harrison P. Elizabeth Blackwell’s struggle to become a doctor. Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Accessed 23 January 2022. www.radcliffe.harvard.edu/news-and-ideas/elizabeth-blackwells-struggle-t....

National Library of Medicine. Elizabeth Blackwell: “That girl there is doctor in medicine” part II. Accessed 23 January 2022. www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/blackwell/career.html.

Nimura JP. The doctors Blackwell: How two pioneering sisters brought medicine to women and women to medicine. Norton WW & Company, Inc. 2021.

Wirtzfeld DA. The history of women in surgery. Can J Surg 2009;52:317-32

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |