Well before my wife died from a 9-year-long progressive deep dementia, she signed up to have her lifeless body donated to the Department of Anatomy at UBC. I believe her body was used for teaching and research. After 1½ years, in accordance with the donation agreement, her remains were cremated and returned to me. I must admit to the pang in my heart when I opened the simple urn containing her cremated ashes. We were married for close to 70 years. Now her body was reduced to a bag of ashes. Once I got over my difficult feelings, I became glad on her behalf that her wish had been fulfilled. Anatomy is foundational for medical education, and she has contributed to the education of future doctors and health professionals.

Anatomy is the oldest scientific discipline in medicine. Egyptians, with their embalming methods, and other ancient people with religious ceremonies of human sacrifices, must have known some anatomy. In the Western culture, it was Hippocrates (460 BCE–375 BCE) who separated medicine from philosophy by enquiring about the structure of living creatures. He was the first medical man to write about anatomy. The second person of stature was Claudius Galenus, better known as Galen (129–216), a Greco–Roman physician with an extraordinary influence on medical science. His emphasis was on non-existent humors in the body, which he mistakenly believed to be important in disease. His anatomical findings were based on animal dissections, so some of his observations were barely applicable to humans, yet many of his writings and teachings, including the incorrect anatomical descriptions, became medical dogma for about 1300 years. Ironically, over those years, attempts to disprove many of Galen’s false formulations drove positive developments in medical teaching, particularly in the area of anatomy.

Three distinguished dissectionists have made anatomy basic to medical education.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) was an engineer, a sculptor, and artist. He trained in anatomy to be able to depict the ideal human form. He abandoned Galen’s erroneous findings and relied entirely on his direct observations. He was the first to develop drawing techniques of anatomy using cross-sections and angles. Among his over 750 drawings, he produced the first accurate depiction of the human spine and showed a cross section of a human male and female in the act of coitus. Da Vinci’s art was driven by the act of discovery itself, and his notebooks and drawings were not published during his lifetime. They were found and published over 100 years after his death, then with a great impact.

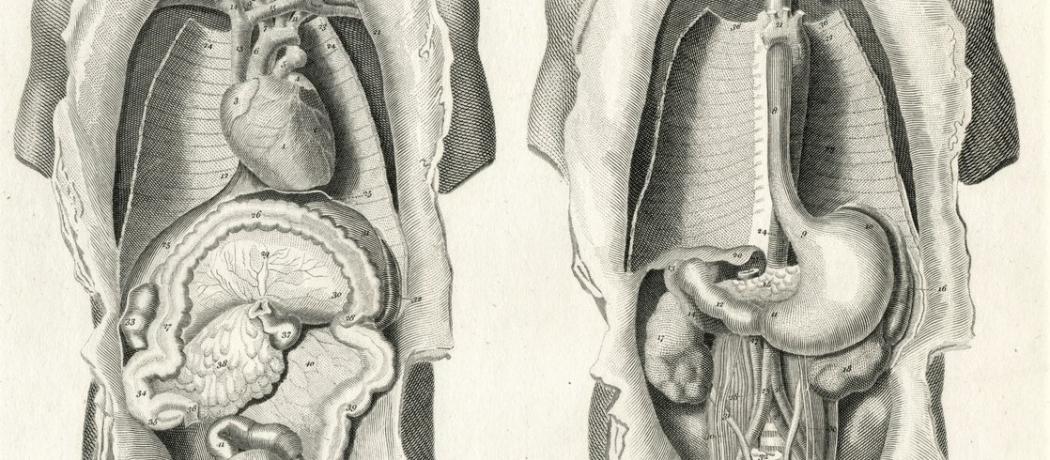

Shortly after da Vinci, Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) became the most famous anatomist of his time. Born in Brussels, he came from a long line of a medical family: his great-grandfather taught medicine, his grandfather was a royal physician to the Emperor Maximilian, his father was a pharmacist both to Emperor Maximilian and Charles V. He started with a military career, but switched to medicine, studying the theories of Galen. On graduation he was offered a position in surgery and anatomy. He soon discovered that all of Galen’s research was restricted to animals. Unlike Galen, Vaselius was able to secure a supply of human cadavers for dissection—bodies of executed criminals. As physician and author of On the Fabric of the Human Body in Seven Books, his highly detailed and intricate plates became instant classics. Yet it still took another century for Galen’s theories and influence to fade.

William Harvey (1578–1657), an English physician and anatomist, described in detail the circulation of blood being pumped by the heart to the brain and the rest of the body. He disproved Galen’s theory that the liver was the origin of venous blood. Initially his discovery was met with derision and abuse, and it took 20 years for his basic theory of the circulation of blood to be generally accepted. Even Harvey had problems: not having microscopes, he did not recognize the role of capillaries between arteries and veins, and mistakenly proposed that arterial blood permeated the flesh and was sucked up by the veins.

It took another 200 years, to the 19th century, when the macroscopic study of dissected organs was established, and with the use of microscopes a new field opened up to anatomical scholarship. Anatomy teaching, including classroom lectures, anatomical models, and guided dissection of cadavers, has become an essential base in medical education. However, in the last 20 to 30 years, time allocated for anatomy curricula has been gradually reduced by using electronic visual technology instead of hands-on dissection. Administrators also have to face the economic issues related to running dissection laboratories and not having adequate levels of teaching staff available.

Anatomy teaching methods will likely change further. However, studying anatomy on a human cadaver will remain an irreplaceable, dramatic, and exceptional privilege of great importance to the student: it will remain the first step in becoming a doctor.

—George Szasz, CM, MD

Suggested reading

Lavaud S. Leonardo da Vinci: Anatomist and pioneer of modern imaging. Univadis. Accessed 26 July 2023. www.univadis.com/viewarticle/s/leonardo-da-vinci-anatomist-and-pioneer-modern-imaging-2023a1000ekq.

Nutton V. Galen. Encyclopedia Britannica. Accessed 26 July 2023. www.britannica.com/biography/Galen.

Turney BW. Anatomy in a modern medical curriculum. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2007;89:104-107.

Wikipedia. Andreas Vesalius. Accessed 26 July 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andreas_Vesalius.

Wikipedia. History of anatomy. Accessed 26 July 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_anatomy.

Wikipedia. William Harvey Accessed 26 July 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Harvey.

This post has not been peer reviewed by the BCMJ Editorial Board.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |