Review Articles

Successful succession: Evaluating financial capacity, testamentary capacity, and undue influence in BC

ABSTRACT: The ability to manage one’s finances or to make a will can become important under certain circumstances. Physicians are sometimes asked to evaluate the financial or testamentary capacity of their patients, particularly vulnerable, older, and cognitively impaired individuals, and thus can play a vital role in assisting with the legal process of determining one’s capacity. Undue influence may be a factor affecting an individual’s judgment. Identifying signs that signal susceptibility to undue influence can be both clinically and legally relevant, and the British Columbia Law Institute’s recently published guide for recognizing and preventing undue influence can aid in such an evaluation. This review provides guidance for clinicians in assessing patients for financial capacity, testamentary capacity, capacity to assign a power of attorney or a representative, and undue influence, particularly if the individual has been deemed incapable.

Clinical and legal guidance on how physicians can conduct capacity assessments of patients based on statutory and common laws.

According to the Canadian census, the population of British Columbia in 2021 was just over 5 million citizens, and 20.3% were aged 65 years or older.[1] With an aging population, a concomitant increase in the rate of major neurocognitive disorder (i.e., dementia), and the projected largest generational wealth transfer in history as baby boomers get older, decisional capacity in areas such as managing financial affairs, drawing up a will (testamentary capacity), or gifting a large asset becomes important. Elderly individuals are more likely to be vulnerable to exploitation in these areas. The overall prevalence of financial abuse has been estimated to be 4.2% for community-dwelling seniors, based on a contemporary systematic review and meta-analysis;[2] there is a higher likelihood of 14.1% in those who are institutionalized,[3] and even higher rates that can approach 50% in those with major neurocognitive disorder.[4]

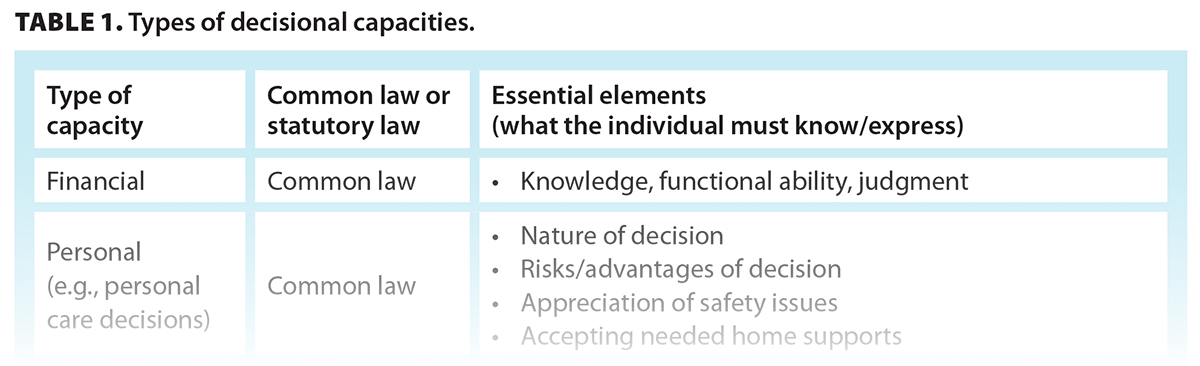

It is a fundamental part of Canadian law that all adults are presumed to be capable. An adult lacks capacity only if they do not meet the requisite test. Physicians are sometimes called upon to assist in determining capacity in these matters. The threshold at which someone is deemed incapable varies depending on their circumstances and what is at stake.[5] In this review, the clinical and legal aspects of these specific types of decisional capacities are discussed, along with the various courses of action once a person is determined to be incapable. Decision making regarding managing one’s personal affairs (e.g., one’s ability to live safely and independently) is not within the scope of this review. The recent changes in provincial legislation that guides the determination of some of these capacities[6] and the recent publication from the British Columbia Law Institute to help guide the assessment and prevention of undue influence in these contexts[7] are highlighted.

Case study: The mercenary late life partner—Part 1

Jack, a moderately wealthy divorced man with three adult children, was in his late 70s when he met Edna, who was then 52, also divorced, with two grown children of her own. Jack and Edna began living together in Jack’s town house. In his early 80s, Jack began to show signs of short-term memory loss after suffering from a mild stroke and subsequently exhibited declining instrumental activities of daily living and increasing dependence on Edna. He was persuaded to assign power of attorney and a representation agreement for health care decisions to Edna.

Appointing a power of attorney or representative

In BC, an adult can appoint an attorney pursuant to a power of attorney. Most powers of attorney in BC are enduring powers of attorney, meaning that the power of attorney remains valid even if the adult becomes incapable. The test for a power of attorney is set out in statutory law [Table 1].[8] Every adult is presumed capable unless they are incapable of understanding the nature and consequences of the proposed enduring power of attorney.[8] Similarly, the test for capacity to appoint a representative to make a medical decision is detailed in statutory law and depends on the type of representation agreement. There are two types of representation agreements: a simpler section 7 agreement and an enhanced section 9 agreement[9] [Table 1]. A standard representation agreement (section 7) requires only that the person is able to understand the decision they are undertaking.[10] For an enhanced section 9 representation agreement, an adult may authorize a representative to decide on a wider scope of interventions, such as determining place of residence, including facility care, or withdrawing life-supporting treatment.

Case study: The mercenary late life partner—Part 2

Jack was hospitalized with another stroke and became hemiplegic. Edna requested that her power of attorney be activated so she could formally manage Jack’s finances. Social work staff asked medical staff to make a capacity assessment, and Jack was found incapable, so the power of attorney was activated due to his substantial cognitive impairment. Over time, Jack’s children became concerned that Edna was misappropriating his funds to her own children and sought legal advice to apply for committeeship to manage his personal and financial affairs. The lawyer asked for a medical opinion.

Letter of instruction and process of assessment

Often, it is a lawyer who requests an assessment from a physician, and the lawyer will typically provide the physician with a letter of instruction. The physician may request one if it is not provided. The letter of instruction should provide background information and set out what type of capacity is at issue and what the legal test is for that type of capacity.[11] A determination of susceptibility to undue influence may also be requested if the legal advisor has concerns. If the assessment is intended to be used in court, the letter should include any relevant court procedures or forms the physician is required to follow.[12]

In general, assessments should be performed under circumstances that optimize sensory input and comfort. The assessor should state the purpose of the evaluation, particularly since questions on these subjects may cause surprise and unease, and enough time should be allotted so one should not feel rushed or overwhelmed when responding. With a language barrier, the use of a professional interpreter is highly recommended, since employing family members or friends can be (though not necessarily by intention) misleading or inaccurate. Virtual visits are now widespread and recent legislative amendments validated the virtual witnessing of will signing (even to have a full virtual will).[6] Nevertheless, especially in the older adult who has sensory and/or cognitive impairment, it is prudent to conduct the interview in person and alone, particularly if undue influence is raised. In most cases, these kinds of assessments should be accompanied by cognitive screening. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment is preferred over the Mini-Mental State Examination because it is more sensitive in detecting frontal executive deficits.[13] There is no cutoff score to indicate whether the person is capable or not, but a positive screen for major neurocognitive disorder or even mild neurocognitive disorder (i.e., a mild cognitive impairment) will give a higher index of suspicion for incapacity.[14]

Financial capacity

Generally, decision making falls on a spectrum of legal capacity where the level of capacity required to decide is dependent on the complexity of the decision. For example, the capacity to manage finances generally falls on the most stringent end of a spectrum because it necessarily involves many complex cognitive steps and evaluations, whereas capacity to grant a power of attorney is less stringent.

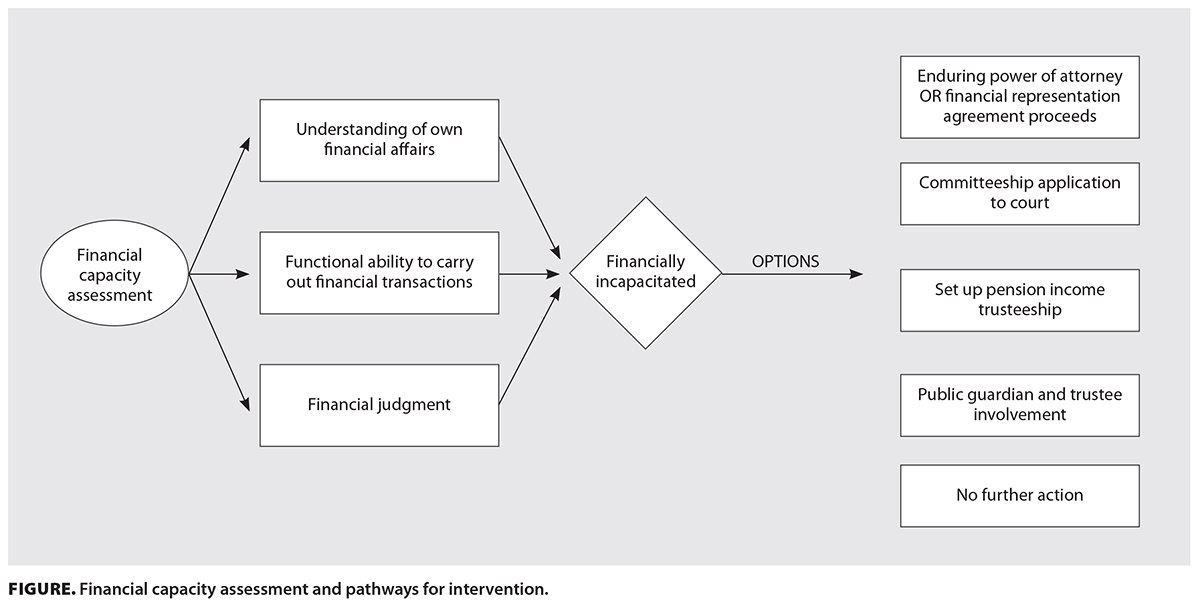

A financial capacity assessment may be requested when concerns are raised about a person’s declining cognitive and functional abilities, impulsivity, or disinhibition, or the possible presence of an abuser or undue influencer. An assessment may be needed to authorize an existing power of attorney or representation agreement or to apply to the court for committeeship (i.e., guardianship).[15] Financial capacity encompasses understanding that certain decisions are necessary, appreciation that those decisions apply to oneself, and reasoning by weighing the risks and benefits of making or failing to make a particular decision.[5,16] Financial capacity involves at least three key elements: knowledge of the extent of one’s finances, functional ability to carry out financial transactions, and financial judgment.

Knowledge of one’s finances includes an understanding of one’s assets (e.g., bank account, real estate, vehicles, investments, valuables), liabilities (e.g., mortgage, loans, credit card and tax debts, obligations owed to dependants), income (e.g., government and private pensions, investment income), and expenses (e.g., rent, loan payments, utilities, phone/Internet, tax payments, cost of care). Even if the person can demonstrate a working knowledge of the nature of their finances, there can be a task-specific deficit regarding financial management such that the individual cannot implement the necessary action. Collateral information is especially important in these situations because the person may come across as functioning “normally” yet be quite impaired. Typically, this is seen in those with frontal executive dysfunction rather than those with just memory dysfunction, such as in major neurocognitive disorder caused by vascular events in the frontal cortex or certain areas subcortically, frontotemporal major neurocognitive disorder, and sometimes Lewy body major neurocognitive disorder. Initially, Alzheimer disease typically affects memory and, therefore, one’s financial knowledge, but in later stages, the disease can also affect frontal executive areas.

Judgment can be impacted by pathology in certain frontal areas, such as the orbitofrontal region.[17] Poor judgment often accompanies poor knowledge and/or poor executive function in relation to finances, but if judgment becomes the sole reason for deeming someone incapable, it can sometimes be challenging to prove since it is interpreted subjectively by the assessor. For instance, a person may be spending extravagantly but still within their means. Clues that might help the assessor decide could be a departure in the person’s usual spending habits or other personality changes that do not relate to spending. Potentially treatable primary or concurrent mental disorders, such as bipolar disorder, substance use disorder, and gambling disorder, would need to be ruled out. It is also possible that extravagant spending is a lifelong pattern that is more reflective of personality and upbringing than poor judgment. More broadly, a person’s current ability to manage finances needs to be considered longitudinally since they may have had very little financial responsibility in their lifetime because someone else handled it for them in the past.

There are validated measures that incorporate financial management abilities as a subscale in an overall functional assessment, such as the Independent Living Scales[18] and the Cognitive Competency Test,[19] but they are not practical enough to be administered by most physicians, and they involve training. Instead, the person can be asked to do some simple arithmetic or identify and count currency to supplement the assessment.

The finding of incapacity may trigger several options to protect the person’s finances and ensure bills and debts are paid [Figure]. The enduring clause for a pre-existing power of attorney[8] or representation agreement[9] may come into effect, or a committeeship application may be initiated. These options are facilitated by a medicolegal letter or a report from the physician. One no-cost alternative to committeeship that merits consideration is the application for a pension income trusteeship, pertaining to federal benefits only, such as Old Age Security and the Canada Pension Plan, by assigning a private trustee, who can be any trusted individual(s) or even a not-for-profit organization (e.g., the Bloom Group in Vancouver). Unfortunately, this type of trustee will not be able to manage other aspects of financial affairs. A certificate of incapability form is filled out by the physician.[20] For those situations where financial abuse is alleged, the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee[21] may become involved. After an investigation, the Public Guardian and Trustee may ask a physician to complete the Public Guardian and Trustee–specific certificate of incapability before intervening. Two certificates are required, and one of them should be completed by a designated trained assessor, who is usually a social worker. These details are set out in section 3 of the Adult Guardianship Act.[22] There is some financial compensation for physicians who undertake a capacity assessment at the request of the Public Guardian and Trustee.

The finding of incapacity may trigger several options to protect the person’s finances and ensure bills and debts are paid [Figure]. The enduring clause for a pre-existing power of attorney[8] or representation agreement[9] may come into effect, or a committeeship application may be initiated. These options are facilitated by a medicolegal letter or a report from the physician. One no-cost alternative to committeeship that merits consideration is the application for a pension income trusteeship, pertaining to federal benefits only, such as Old Age Security and the Canada Pension Plan, by assigning a private trustee, who can be any trusted individual(s) or even a not-for-profit organization (e.g., the Bloom Group in Vancouver). Unfortunately, this type of trustee will not be able to manage other aspects of financial affairs. A certificate of incapability form is filled out by the physician.[20] For those situations where financial abuse is alleged, the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee[21] may become involved. After an investigation, the Public Guardian and Trustee may ask a physician to complete the Public Guardian and Trustee–specific certificate of incapability before intervening. Two certificates are required, and one of them should be completed by a designated trained assessor, who is usually a social worker. These details are set out in section 3 of the Adult Guardianship Act.[22] There is some financial compensation for physicians who undertake a capacity assessment at the request of the Public Guardian and Trustee.

There can be situations where the person is deemed incapable of managing finances but no further action is required. This can occur, for example, when a trustworthy person is already informally assisting with financial affairs or a paid professional such as a financial advisor or a trust manager is already involved. Alternatively, the person may still be considered marginally capable if they exercise sufficient judgment in allowing others to help, even though they may lack sufficient knowledge or functional abilities to manage their finances. However, presuming that these parties are always acting in the person’s best interest can be fraught with hazard, so ensuring that a formal legal mechanism, whether it is a power of attorney, a representation agreement, or something else, is initiated for oversight would be preferred in most cases.

Case study: The mercenary late life partner—Part 3

Jack’s first will indicated that his estate was to be left to his three children in equal shares. When Edna moved in, Jack made a second will, which divided his estate equally between Edna and his three children, giving each a 25% share. When Jack became increasingly dependent on Edna after the last stroke, he made his last will, appointing Edna as his executor and residuary beneficiary. The will gave substantial legacies to Edna’s son and daughter and only $100 to each of Jack’s own three children. Jack’s children were unaware of these changes.

Testamentary capacity

Testamentary capacity requires that (1) the person understands the nature and act of making a will and its effects—in other words, that the adult is giving away their property and belongings when they die to certain people/entities under the will; (2) the person understands the extent of their estate—this involves a broad appreciation of the person’s assets and value but not exact figures; (3) the person understands the claims of those who might expect benefit from the will maker (both those persons included and those excluded)—this includes spouses, children, and other family members; and (4) the will maker does not have a mental illness that influences them to make decisions in their will that they would not have otherwise made absent the illness.[11,23] The test for making a will is a common law test based on Banks v. Goodfellow,[23] meaning that it is not written into statutory law. A person may lack the capacity to manage their finances, but they may still have the capacity to make a will, power of attorney, or representation agreement. Physicians should be aware that the will maker’s decisional capacity can be overborne by undue influence.

Case study: The mercenary late life partner—Part 4

Prior to his death and before his last will, Edna discouraged other people from seeing or talking to Jack, especially his children, on the pretext that he was not well and visits would tire him. At the same time, she encouraged her own children to visit frequently. She would hint strongly that his own uncaring family did not deserve to inherit his estate.

Undue influence

Physicians are sometimes asked to assess patients for susceptibility to undue influence, usually in conjunction with a request for an opinion on testamentary capacity or capacity to manage finances. Undue influence is a separate matter from mental capacity required to perform a legally significant act like making a will or gift or granting a power of attorney. An assessment of mental capacity does not normally address susceptibility to undue influence in the absence of a specific request to cover it in the opinion. Nevertheless, concern about undue influence often arises in association with concerns that family members or financial and legal advisors raise about someone’s financial and testamentary capacity.

Undue influence is the legal term for pressure or deception that overcomes the free will of another person and induces the person to carry out a legal act in accordance with the wishes of the influencer rather than those of the victim.[24] Undue influence is not mere persuasion;[25] it is the imposition of the influencer’s will to the extent that the victim cannot be considered to be acting freely. Benefit to the influencer is not essential for undue influence as long as the act desired by the influencer is procured because the victim believes there is no other choice open. The validity of a legal act or transaction depends not only on the presence of the requisite mental capacity to perform the act, but also on the act being the product of a freely operating independent mind.[26]

The legal implications of undue influence differ somewhat, depending on whether the undue influence relates to the terms of a will (testamentary undue influence) or to an act or transaction intended to take effect in the victim’s lifetime (nontestamentary or inter vivos undue influence). Nontestamentary undue influence can range from outright coercion to manipulation through misinformation or fear, or simply wearing down the victim by importuning over a period of time.[27] Testamentary undue influence, by contrast, has usually been said to require coercion.[28,29] However, what amounts to coercion in particular cases may vary with the vulnerability of the victim. Verbal or psychological pressure, without overt threats, can amount to undue influence affecting a will if the victim is highly dependent on the influencer or is severely weakened in mind and body.[27,30] Providing misinformation that leads the victim to make a will that would not have been made otherwise also amounts to undue influence.[28]

In addition to being a legal concept, undue influence is actual financial abuse. Influencers exploit relationships of physical and economic dependence, confidence, and trust. Typically, influencers operate by isolating the victim physically or socially. It is especially common for influencers to systematically misinform their victims and control victims’ sources of information. Language barriers and difficulty with cross-cultural communication often play into the influencer’s hands as well.

Detection of undue influence by legal advisors, social workers, and others in a position to help the victim is often complicated by conflicting emotions and misplaced familial loyalty on the part of the victim toward the influencer, who is often a family member or someone in whom the victim has placed trust. This often manifests in denial by the victim when asked questions intended to aid in determining whether they are being coerced, manipulated, or otherwise abused. While anyone can be a victim of undue influence regardless of age and mental acuity, cognitive impairment is broadly recognized as a factor that increases the risk of victimhood.[31-34] Major neurocognitive disorder involves impairment in one or more cognitive domains, which can affect testamentary capacity or susceptibility to undue influence [Table 2].[7] Factors that influence dependency, such as physical conditions that create difficulty in activities of daily living, behavioral disorders, and substance abuse, are also recognized as risk factors for undue influence.[31]

Lists of risk factors (“red flags”) typically associated with undue influence or the potential for it to occur can be found in medicolegal literature.[7,31,35] These lists comprise both personal characteristics (physical and mental conditions) and circumstances such as physical or economic dependency, impaired mental function, illiteracy, recent bereavement, and language barriers, to name a few. No empirical studies have verified these lists of red flags in terms of prevalence or importance, but they are recognized as significant indicia by civil courts.[31]

A request for assessing susceptibility to undue influence should explain the legal concept of undue influence and ask a question along these lines: “Are there medical reasons why the client is more vulnerable to undue influence in making decisions?”[7] Another way to express the essential question to which the assessment should be addressed is “Can this person say no to relatives and others despite pressure from them to say yes?” Physicians who receive such a request may find helpful background information in the British Columbia Law Institute’s guide Undue Influence: Recognition and Prevention. A Guide for Legal Practitioners (including case studies such as “The mercenary late life partner,” as adapted here) and the accompanying reference aid, which encapsulates red flags associated with susceptibility to this form of financial abuse.[7] While the guide is intended primarily for an audience of lawyers and notaries, it explains why physicians may be asked to give opinions on susceptibility to undue influence and how the request and the opinion should be framed to be as informative as possible for the assessing physician and the requesting legal practitioner, respectively.

If a video assessment is unavoidable, care should be taken at the start to confirm that the subject is alone and no one else is within earshot. The subject could be asked to provide a 360-degree scan of the surroundings to verify this. If this is impractical because of the subject’s condition, it would be best to postpone the assessment until an in-person interview can take place. If there are serious concerns that undue influence is actually being exerted, it is essential to conduct the assessment interview in person with the subject alone, except for a professional interpreter when needed.

There is disagreement in the medicolegal literature regarding whether information about patterns of will making by the patient is relevant to the medical assessment of susceptibility to testamentary undue influence. The International Psychogeriatric Association Task Force on Testamentary Capacity and Undue Influence considered that shifts from previous will-making patterns are relevant to the medical assessment of susceptibility.[32] Plotkin and colleagues disagreed on the ground that the significance of will-making behavior is outside the expertise of medical assessors and rests with the court.[33] It is important to keep in mind that the medical assessor’s role is to give an opinion on susceptibility to undue influence, not to determine whether the patient has actually been subjected to undue influence.

After the assessment

The physician may be asked or required to take further steps after assessing a person’s capacity. For example, the physician may be asked to affirm an affidavit (a written statement taken under oath), which is often drafted by a lawyer. The physician may be asked to prepare a written report, which could be used in various ways, such as to trigger an event, to discuss in negotiations, or for court proceedings. Writing the report is not compensable by MSP. For court proceedings, the physician may be cross-examined on their opinion or the affidavit they made. The physician’s notes may be subpoenaed. The physician’s role in any proceeding will be either a fact witness or an expert witness. The physician may be called as a fact witness and asked questions such as when and where the patient was examined and what was observed. The physician may be called as an expert witness to provide opinion evidence on a person’s capacity.

Summary

Capacity assessments by physicians can play a vital role in serving the best interests of their patients. This review is intended to provide clinical and legal guidance on how physicians can proficiently conduct capacity assessments in light of statutory and common laws that inform practice. A list of online resources for the various agencies discussed is included in the Box.

Competing interests

None declared.

BOX. Resources for evaluating financial capacity, testamentary capacity, and undue influence.

-

British Columbia Law Institute: Undue influence: Recognition and prevention. A guide for legal practitioners. 2022. www.bcli.org/wp-content/uploads/undue-influence-recognition-prevention-guide-final-3.pdf

- Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia: www.trustee.bc.ca

- Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia: Incapability assessments: A review of assessment and screening tools. 2021. www.trustee.bc.ca/documents/sta/incapability_assessments_review_assessment_screening_tools.pdf

- Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia: Adult information sheet: Assessing an adult’s ability to manage their financial affairs. 2016. www.trustee.bc.ca/reports-and-publications/Documents/Adult%20Information%20Sheet.pdf

- Attorney General of British Columbia: Enduring power of attorney [form]. 2011. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/managing-your-health/incapacity-planning/enduring_power_of_attorney.pdf

- Attorney General of British Columbia: Representation agreement (section 9) [form]. 2011. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/managing-your-health/incapacity-planning/representation_agreement_s9.pdf

- Service Canada: Agreement to administer benefits under the Old Age Security Act and/or the Canada Pension Plan by a private trustee [form]. https://catalogue.servicecanada.gc.ca/apps/EForms/pdf/en/ISP-3506_OAS.pdf

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Statistics Canada. Census of population. 2021. Accessed 17 January 2024. www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/index-eng.cfm.

2. Yon Y, Mikton CR, Gassoumis ZD, Wilber KH. Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e147-e156.

3. Yon Y, Ramiro-Gonzalez M, Mikton CR, et al. The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Public Health 2019;29:58-67.

4. Rogers MM, Storey JE, Galloway S. Elder mistreatment and dementia: A comparison of people with and without dementia across the prevalence of abuse. J Appl Gerontol 2023;42:909-918.

5. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1635-1638.

6. Wills, Estates and Succession Act, SBC 2009, Chapter 13. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/09013_01.

7. British Columbia Law Institute. Undue influence: Recognition and prevention. A guide for legal practitioners. Vancouver: 2022. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bcli.org/wp-content/uploads/undue-influence-recognition-prevention-guide-final-3.pdf.

8. Power of Attorney Act, RSBC 1996, Chapter 370. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96370_01.

9. Representation Agreement Act, RSBC 1996, Chapter 405. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96405_01.

10. BC Centre for Palliative Care. What you need to know about standard representation agreements (section 7). 2021. Accessed 17 January 2024. https://bc-cpc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/RA7-Guide_SPREAD.pdf.

11. The British Medical Association, the Law Society, Keen AR. Assessment of mental capacity: A practical guide for doctors and lawyers. 5th ed. London, UK: London Law Society Publishing; 2022.

12. Court Rules Act, Supreme Court Civil Rules, 2009, BC Reg 168/2009. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/168_2009_00.

13. Pinto TCC, Machado L, Bulgacov TM, et al. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr 2019;31:491-504.

14. Bejenaru A, Ellison JM. Medicolegal implications of mild neurocognitive disorder. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2021;34:513-527.

15. Patients Property Act, RSBC 1996, Chapter 349. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96349_01.

16. Adult Guardianship Act, Statutory Property Guardianship Regulation, 2014, BC Reg 115/2014. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/115_2014.

17. Fellows LK. The role of orbitofrontal cortex in decision making: A component process account. Ann NY Acad Sci 2007;1121:421-430.

18. Baird A. Fine tuning recommendations for older adults with memory complaints: Using the Independent Living Scales with the Dementia Rating Scale. Clin Neuropsychol 2006;20:649-661.

19. Zur BM, Rudman DL, Johnson AM, et al. Examining the construct validity of the Cognitive Competency Test for occupational therapy practice. Can J Occup Ther 2013;80:171-180.

20. Service Canada. Agreement to administer benefits under the Old Age Security Act and/or the Canada Pension Plan by a private trustee [form]. 17 January 2024. https://catalogue.servicecanada.gc.ca/apps/EForms/pdf/en/ISP-3506_OAS.pdf.

21. Public Guardian and Trustee of British Columbia. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.trustee.bc.ca.

22. Adult Guardianship Act, RSBC 1996, Chapter 6. Accessed 17 January 2024. www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96006_01.

23. Banks v. Goodfellow, [1870] 5 LR QB 549 (Eng QB).

24. Royal Bank of Scotland Plc v. Etridge (No. 2), [2001] UKHL 44, [2002] 2 AC 773.

25. Daniel v. Drew, [2005] EWCA Civ 507.

26. Geffen v. Goodman Estate, [1991] 2 SCR 353.

27. Tribe v. Farrell, [2006] BCCA 38.

28. Boyse v. Rossborough, [1857] 6 HLC 2, 10 ER 1192.

29. Vout v. Hay, [1995] 2 SCR 876.

30. Wingrove v. Wingrove [1885] 11 PD 81.

31. Herrmann N, Whaley KA, Herbert DJ, Shulman KI. Susceptibility to undue influence: The role of the medical expert in estate litigation. Can J Psychiatry 2022;67:5-12.

32. Peisah C, Finkel S, Shulman K, et al. The wills of older people: Risk factors for undue influence. Int Psychogeriatr 2009;21:7-15.

33. Plotkin DA, Spar JE, Horwitz HL. Assessing undue influence. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law 2016;44:344-351.

34. Shulman KI, Cohen CA, Kirsh FC, et al. Assessment of testamentary capacity and vulnerability to undue influence. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:722-727.

35. Silberfeld M. Susceptibility to undue influence in the mentally impaired. Estates, Trusts & Pensions J 2002;21:331-344.

Dr Chan is a clinical professor in the Department of Psychiatry, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry, at the University of British Columbia. Mr Blue is a senior staff lawyer at the British Columbia Law Institute. Ms Clough is a partner at Clark Wilson LLP and practises in estates, trusts, incapacity, and elder law.