Sexually transmitted diseases in the pediatric patient

The diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease in a prepubertal child must prompt an evaluation for sexual abuse. Because many of the organisms causing sexually transmitted diseases can be acquired by nonsexual means, the task of proving or disproving infection by sexual abuse can sometimes be challenging. Commonly encountered sexually transmitted diseases indicative of sexual abuse in the pediatric patient include gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis.

The possibility of sexual abuse must be considered when children are diagnosed with certain STDs and both vertical and horizontal transmission have been excluded.

When evaluating a child for possible sexual abuse, a clinician must always consider testing for the presence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). Each situation demands an individualized approach, taking into consideration the circumstances of the assault, the age of the child, the characteristics of the alleged offender, and the prevalence of STDs in the community. Unnecessary physical and psychological trauma to the child must be avoided. If an STD is identified, treatment needs to be initiated. Prophylactic treatment for STDs is not routinely recommended in children because of the low risk of transmission of infection, the low prevalence of STDs in pediatric sexual abuse, and because good follow-up is generally assured. The presence of an STD is also an important piece of medicolegal evidence.

In 1998, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided guidelines for when to consider screening for STDs in prepubertal children.[1] They recommended identifying and testing in situations involving a high risk for transmission of a sexually transmitted infection. This would include when a suspected offender is known to have an STD or be at high risk for STDs, when a child has signs or symptoms of an STD, and when the prevalence of an STD is high in a community. Other experts have also suggested screening if there have been multiple perpetrators or an unknown perpetrator, if there is a sibling or household contact with an STD, and if there has been genital injury as a result of the abuse.

Once a sexually transmitted disease has been diagnosed, it may be challenging to determine whether the infection was transmitted by sexual contact or otherwise. Many of the common STDs can be transmitted vertically from mother to infant, and often colonization with these organisms can persist for months or years. Other infections are common in nongenital locations in the pediatric age group and can be transferred to the genitalia by autoinoculation or by child-to-child contact. The following review of commonly encountered sexually transmitted diseases indicates when an association with sexual abuse in the pediatric patient should be considered (see the Table).

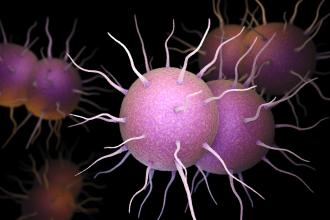

Neisseria gonorrhoeae, a Gram-negative diplococcus, causes disease primarily by infecting the columnar and pseudostratified epithelium of the urethra, estrogenized endocervix, conjunctivae, and prepubertal vagina. It can also cause anorectal infection, pharyngitis, and disseminated disease featuring arthritis, dermatitis, meningitis, and/or endocarditis. The bacterium is fastidious and unlikely to be transmitted through casual contact. It can be transmitted from mother to infant through an infected birth canal. Perinatal colonization can persist for up to 6 months.[2] Gonococcal (GC) infection beyond the newborn period is almost always sexually transmitted with the rare exception of transmission from an infected parent due to poor hygiene. N. gonorrhoeae can survive up to 24 hours on fomites (toilet seats, towels) in moist purulent secretions.[3] On rare occasions infection may occur during child sexual play but the index patient is likely to have been sexually abused. Sexual abuse should be strongly suspected in any prepubertal child with GC infection.

GC disease is the most common sexually transmitted disease found in sexual abuse victims, with a prevalence of 2% to 5%[1] and concurrent chlamydia infection is common.[4] The incubation period is usually 2 to 7 days.[4] In prepubertal girls, the lack of estrogenization and the alkaline pH of the secreted mucus allows infection of the vagina, causing symptomatic vulvovaginitis in this age group. Gonococcal urethritis in the prepubertal male is uncommon and infections of the throat and rectum are usually asymptomatic.

The gold standard for diagnosis is culture. Swabs should be used to obtain specimens from genital, rectal, and pharyngeal sites if sexual abuse is suspected. Vaginal specimens are adequate in prepubertal girls and endocervical specimens are unnecessary. In boys, meatal specimens of discharge, if present, are adequate; otherwise, a urethral specimen should be obtained. Specimens should be immediately inoculated on selective media that inhibit normal flora and nonpathogenic neisseria organisms. Otherwise, the specimen should be placed in transport medium pending inoculation as N. gonorrhoeae is extremely sensitive to drying and temperature changes. Because N. gonorrhoeae can be confused with other neisseria species that colonize the genitourinary tract and pharynx, confirmatory testing needs to be performed using enzyme substrate, direct fluorescent antibody, or carbohydrate utilization. Nucleic acid amplification methods (polymerase chain reaction and ligase chain reaction) have recently shown promise with good specificity and sensitivity on specimens that are easier to collect (vaginal washings, urine), however, they are not solely reliable for diagnosis in this population, since false-positives can occur.[1,4-6]

Because of the high prevalence of penicillin-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, a third-generation cephalosporin such as ceftriaxone is recommended as initial therapy in children. For uncomplicated local disease, ceftriaxone (125 mg i.m.) in a single dose or spectinomycin (50 mg/kg i.m., maximum 2 g) in a single dose is recommended. For older children, oral cefixime (400 mg) in a single dose may be used. In addition, therapy for presumptive chlamydia infection is also indicated, with erythromycin (50 mg/kg, maximum, 2 g) in 4 divided doses per day for 7 days, or azithromycin (20 mg/kg, maximum, 1 g) in a single dose.[4,7]

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacterial agent that is associated with neonatal conjunctivitis, trachoma, pneumonia in young infants, genital tract infection, pharyngitis, and lymphogranuloma venereum. Infants born to infected mothers can present with conjunctivitis and/or pneumonia, with a vertical transmission rate of about 50%.[4] The presence of C. trachomatis infection in children younger than 3 years may represent persistent perinatal colonization. However, genitourinary tract infection of a child older than 3 years is indicative of sexual acquisition.[1,4] Fomite transmission has not been documented.

The prevalence of C. trachomatis infection in sexually abused children is 2% to 13%.[3] A significant proportion of these may be a result of perinatal transmission. In prepubertal girls infection causes urethritis and vaginitis; in boys it causes nongonococcal urethritis and epididymitis. Infections are commonly asymptomatic and may persist for months or years. The incubation period is variable, but is usually 1 week.

Definitive diagnosis is made by isolating chlamydial intracellular inclusions in tissue culture. Because C. trachomatis is an obligate intracellular organism, a cotton or Dacron swab should be used to obtain cells, not just exudate. The vagina should be swabbed in girls and the anus should be swabbed in both boys and girls. The yield from urethral specimens in boys is too low to justify testing, and is recommended only if urethral discharge is present. Testing of pharyngeal specimens is also not recommended because of low yield.[1] Specimens should be placed on ice and transported to a laboratory immediately or stored at 4°C until the culture can be set up.

Other nonculture detection systems, including enzyme immunoassays, direct fluorescent antibody tests, and DNA probes lack sufficient specificity to be used in children at rectogenital sites. DNA amplification methods have not been approved for any sites in children.[1,4-6]

Treatment for C. trachomatis genital tract infection in children 6 months to 12 years of age is azithromycin (20 mg/kg, maximum 1 g) in a single dose. For children younger than 6 months of age, erythromycin (50 mg/kg) in four divided doses per day for 7 days is recommended.[4]

Treponema pallidum is a motile spirochete and the organism that causes syphilis. Infection can occur in utero (congenital syphilis) or through sexual transmission. Congenital syphilis transmission can occur at any time during pregnancy or at birth. This clinical syndrome has been well described in the literature.[4] Acquired syphilis is almost always contracted through direct sexual contact, and thus sexual abuse has to be suspected in any young child who presents with primary or secondary disease beyond early infancy.[4,5,8] The incubation period for primary syphilis is 10 to 90 days.[4]

The prevalence of syphilis among children suspected of being sexually abused is zero to 1.8%.[1] The diagnosis is easy to miss because of the low index of suspicion and the lesions can mimic other common diseases. Because of this, routine screening of sexually abused children has been recommended. Screening is inexpensive and effective using nontreponemal tests such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test, or automated reagin (ART) test. False-negatives can occur in early primary syphilis, late latent syphilis, and when the antibody titre is very high. False-positive results occur routinely with these tests in 1% to 2%1 of cases with certain infections and diseases and during pregnancy. Therefore, all positive nontreponemal tests must be confirmed by a specific treponemal test such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test or the microhemagglutination test for T. pallidum (MHA-TP).

The recommended treatment for primary and secondary syphilis is benzathine penicillin G (50 000 U/kg i.m., maximum 2.4 million units) in a single dose.[4] All children should have examination of the cerebrospinal fluid prior to treatment to exclude the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. Treponemal tests remain positive for life even after treatment. Quantitative nontreponemal antibody tests are required to assess the adequacy of treatment.

Infections caused by the herpes simplex virus (HSV) are not commonly described following child sexual assault and the risk of acquiring the infection through sexual abuse is unknown.[1,5] Genital herpes is characterized by painful, vesicular or ulcerative lesions of the skin and mucous membranes of the male or female genital tract and is usually caused by HSV type 2. HSV type 1 infections usually occur in the mouth. However, either HSV-1 or HSV-2 can be found in the oral or genital region. The incubation period for the virus is 2 to 20 days.

Perinatal transmission of HSV-2 can occur by ascending infection or during birth through an infected maternal genital tract. In children and infants beyond the neonatal period, HSV-2 infection usually results from direct contact with infected genital lesions or secretions. Genital HSV-1 infection can be from oral-genital contact or from autoinoculation of the virus from the mouth of the child. Transmission from a finger infection in a caregiver causing primary herpetic vulvovaginitis in a child has been described.[1] Fomite transmission has not been documented.[1,3]

In summary, nonsexual and sexual transmission of HSV-1 can cause genital infection. In the absence of simultaneous oral or finger lesions in the child or caregiver, the diagnosis of sexual abuse must be considered. Except for vertical transmission at birth, HSV-2 genital infection in a child is considered to be sexually transmitted.

The gold standard for diagnosis is viral cell culture. The highest yield occurs when the base of a lesion is rubbed with a cotton swab and placed in special transport media. Culture and typing to distinguish between type 1 and 2 should be done in all suspicious lesions.

Oral therapy initiated within 6 days of disease onset can shorten the duration of illness and limit viral shedding by 3 to 5 days.[4] The recommended treatment is acyclovir (80 mg/kg) in 4 divided doses per day for 7 to 10 days.[4]

Anogenital warts caused by human papilloma virus infection are not commonly diagnosed in children.[1] When they are seen, it is generally the result of nonsexual transmission. The anogential strains prefer moist mucosal surfaces found in the perineal area. The classic lesion is called condyloma acuminatum and appears as a flesh-colored to gray, multidigitated, papillomatous growth. These lesions can range in size from less than a millimetre to several square centimetres in diameter if multiple lesions coalesce. Other common appearances of lesions include small, dome-shaped, red or pigmented papules. Most anogenital warts are asymptomatic, but occasionally bleeding, pain, itching, or burning can occur.

Nonsexual acquisition may be the most common mode of transmission among children younger than 3 years of age.[9] Perinatal vertical transmission is well documented and the absence of a clear maternal history does not preclude this. The confusion lies in the fact that there can be an extremely variable and prolonged latency period of up to 3 years before the appearance of visibly detectable genital warts.[5,9] Autoinoculation and heteroinoculation can also occur.[1] While sexual abuse should be considered, caution is advised in interpreting the implications of genital or anal warts in cases beyond the neonatal period. Fomite transmission has never been demonstrated.[5,8]

Diagnosis is based on appearance of the lesions. Biopsy may be helpful in identifying the human papilloma virus in puzzling lesions. None of the currently available treatments, including topical medication, laser ablation, or surgical removal, can eradicate the virus, eliminate the warts, or prevent recurrence. There is a high spontaneous resolution rate over 2 years, making active nontreatment an acceptable option. This does not affect the risk of developing genital cancers, which have been associated with some HPV subtypes.[3] In the setting of extensive and refractory lesions, consider testing for HIV infection or other immunocompromised states.

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan that infects the human genitourinary tract and is transmitted by direct genital contact or from infected mother to neonate. Neonatal infection can persist up to 1 year.[2,3] Limited data are available about the risk of acquisition after sexual abuse of children. Beyond infancy, however, the presence of T. vaginalis in a vaginal specimen from a child is strongly suggestive of sexual abuse. Fomite transmission has not been documented in children.[2,3] T. vaginalis causes vaginitis in females and nongonococcal urethritis in males. Infections are typically asymptomatic but may present with a discharge. The incubation period is from 4 to 20 days.

Diagnosis is usually made by examination of the urine or a wet mount of the vaginal discharge. The wet mount has a 50% to 75% detection rate.[1,5] Vaginal pH is not useful in prepubertal children. Culture techniques for T. vaginalis and DNA amplification tests have not been evaluated in children.

Treatment is with oral metronidazole (15 mg/kg, maximum 2 g) in three divided doses per day for 7 days, or in a single oral dose (40 mg/kg, maximum 2 g).[4]

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)

Transmission of HIV during sexual abuse has been documented, but the seroconversion rate under these circumstances is unknown.[1,8,10] It is unlikely that infection would occur following a single episode of sexual abuse.[3] Screening of victims for HIV should be considered if there is a history of vaginal or rectal penetration by an unknown perpetrator or multiple perpetrators, if the child has any symptoms suggestive of immunodeficiency or another STD, if there is evidence of genital injury, if the perpetrator is at high risk for HIV infection (i.e., the perpetrator is homosexual, bisexual, or an intravenous drug user), if there is a high prevalence of HIV in the community, or if the parents request screening. Initial testing is by enzyme immunoassay followed by a confirmatory test for HIV antibody such as the Western Blot test. Most infected children will have detectable antibody within 3 to 6 months. It is recommended that antibody testing be done at baseline, then at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

The indications for postexposure prophylaxis are clear for cases of sexual assault when perpetrators are known or likely to be HIV infected. They are less clear for perpetrators of unknown HIV status and some attempt to stratify exposures as high-risk or low-risk may help in the decision-making process. HIV postexposure prophylaxis is likely most effective when provided within 1 hour of exposure, and ideally within 72 hours.[10] The recommended regimen is zidovudine (160 mg/m2) every 6 hours with lamivudine (4 mg/kg) twice a day for ages 3 months to 12 years. For older children, zidovudine (300 mg) twice a day with lamivudine (150 mg) twice a day is recommended.[10] The addition of a protease inhibitor is controversial. Consultation with a pediatric infectious disease specialist is also advised.

Sexual abuse is clearly a risk factor for the acquisition of these infections but the rates of transmission following sexual assault are unknown. There are no well-established protocols for children, except that all children being examined for HIV and other STDs should be considered for hepatitis viral serology and for prophylaxis with immunoglobulin (only available for hepatitis B virus), which may prevent transmission in 75% of cases. [1] Hepatitis B immunization should also be offered to an unimmunized victim as this may also be valuable in preventing disease.[3]

Bacterial vaginosis is a term used to describe a polymicrobial infection featuring the overgrowth of Gardnerella vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis, and various other anaerobic organisms, which leads to a depletion of Lactobacillus species. The presence of G. vaginalis is not necessary for the diagnosis of BV. BV appears to be a marker for sexual activity in adults, but in children the infection may be acquired sexually or nonsexually and its presence alone is not diagnostic of abuse.

Infection in children can be symptomatic or asymptomatic. Diagnosis requires a microscopic examination of the characteristic thin, white discharge for “clue cells” (epithelial cells with clusters of bacteria adhering to the surface) and chemical testing to see if the addition of 10% potassium hydroxide to the secretions results in a fishy odor (whiff test).

Treatment with oral metronidazole (15 mg/kg, maximum 2 g) in three divided doses per day for 7 days should be offered to all symptomatic patients.[4] An investigation for sexual abuse is warranted only if there are other indicators suggesting abuse.

Genitourinary tract colonization by Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum colonization strongly correlate with sexual activity in adults. Infants can become colonized by vertical transmission at the time of birth.[1] Although increased colonization has been demonstrated in sexually abused children, with rates as high as 30% to 50%,[1] these organisms can also be found in nonabused children and so should not be considered as markers for sexual abuse. Routine culture is not recommended. An investigation for sexual abuse is warranted only if there are other indicators suggesting abuse.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipoxvirus and presents as discrete, flesh-colored papules with or without central umbilication. Lesions commonly are found on the face, trunk, and extremities and may also occur in the genital area. The virus is spread by direct contact, including sexual contact, and also by fomites such as towels.[4] Dissemination of lesions usually occurs by autoinoculation.[4] The incubation period is 2 to 7 weeks but may be as long as 6 months.

Diagnosis is usually clinical but can also be made on examination of the material expressed from the central core of a lesion. Treatment options include mechanical removal of central core of the lesion, cautery, liquid nitrogen, or application of other topical preparations. Most lesions resolve spontaneously within 6 to 9 months. An investigation for sexual abuse is only warranted if there are other indicators suggesting abuse.

The diagnosis of an STD in a prepubertal child must raise concern for the possibility of sexual abuse, especially if nonsexual vertical or horizontal transmission has been excluded. In these cases, a report to the Ministry of Children and Family Development is recommended.

Competing interests

None declared.

Table. Implications of sexually transmitted disease diagnoses.

| Diagnosis | Evidence for sexual abuse | Recommended action |

| Gonorrhea | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally | Report to Ministry of Children and Family Development (MCFD) |

| Chlamydia | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally | Report to MCFD |

| Syphilis | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally | Report to MCFD |

| Genital herpes | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally or by autoinoculation | Report to MCFD |

| Anogenital warts | Suspicious if not likely to be acquired perinatally or by autoinoculation | Report to MCFD |

| Trichomoniasis | Highly suspicious if not likely to be acquired perinatally | Report to MCFD |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally or through transfusion | Report to MCFD |

| Hepatitis B or C viruses | Diagnostic if not likely to be acquired perinatally or through transfusion | Report to MCFD |

| Bacterial vaginosis (BV) | Inconclusive | Report if there are other indicators of sexual abuse |

| Genital mycoplasmata | Inconclusive | Report if there are other indicators of sexual abuse |

| Molluscum contagiosum | Inconclusive | Report if there are other indicators of sexual abuse |

References

1. Stewart DC. Outline of STDs in child and adolescent sexual abuse. In: Finkel M, Giardino A (eds). Medical Evaluation of Child Sexual Abuse. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002:111-129.

2. Paschall RT. Detection, treatment and forensic implications of STDs in Children. Presented at the 8th Annual APSAC Colloquium, Chicago, IL, 12 July 2000.

3. Finkel MA, DeJong AR. Medical findings in child sexual abuse. In: Reece RM, Ludwig S (eds). Child Abuse: Medical Diagnosis and Management. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:207-286.

4. Pickering LK, ed. 2000 Red Book: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2000:183-185, 208-212, 254-260, 309-318, 403-404, 413-416, 547-559, 588-589.

5. Frasier L. Sexually transmitted diseases. Presented at the 16th Annual San Diego Conference on Child and Family Maltreatment, San Diego, CA, 21 January 2002.

6. Girardet RG, McClain N, Lahoti S, et al. Comparison of the urine-based ligase chain reaction test to culture for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in pediatric sexual abuse victims. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2001;20:144-147. PubMed Abstract Full Text

7. Darville T. Gonorrhea. Pediatr Rev 1999;20:125-128. PubMed Citation Full Text

8. Jenny C. Medical issues in child sexual abuse. In: Myers JEB, Berliner L, Briere J, et al. (eds). The APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2002:235-247.

9. Darville T. Genital warts. Pediatr Rev 1999;20:271-272. PubMed Citation Full Text

10. Merchant RC, Keshavarz R. Human immunodeficiency virus postexposure prophylaxis for adolescents and children. Pediatrics 2001;108:E38. PubMed Abstract Full Text

Nita Jain, MD, FRCPC

Dr Jain is a clinical instructor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of British Columbia and a staff pediatrician at BC’s Children’s Hospital. She is a member of the Child Protection Service Unit at BCCH and she also has a consulting pediatric practice in Vancouver.

Good