Original Research

The provincial privileging process in British Columbia through a rural lens

Abstract

Background: Privileging and credentialing are key processes for ensuring appropriate scope of clinical practice, with the goal of optimized patient safety. Different processes are used to achieve these goals internationally and across Canada, thus highlighting the importance of context. We explore the perceived impact of British Columbia’s provincial privileging process and dictionaries on rural physicians’ ability to meet the needs of their patients.

Methods: Interviews were conducted with a total of 10 rural physicians, health care administrators, and provincial leaders between May and August 2022. Thematic analysis was used to analyze their responses.

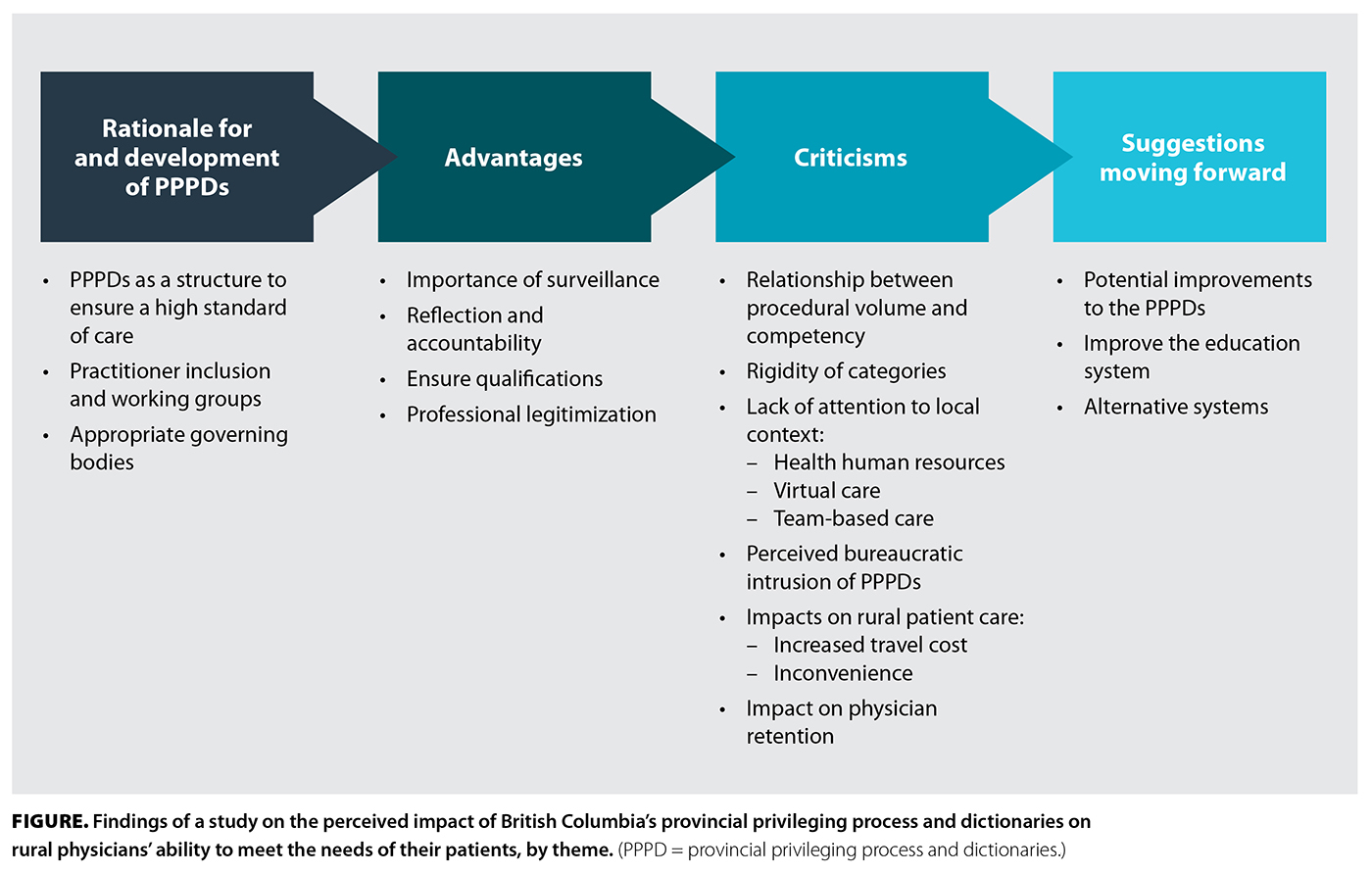

Results: Participants focused on four main themes: the rationale and development of the dictionaries, their advantages, criticisms of the dictionaries, and suggestions for moving forward. Administrators and quality leaders spoke to the first two themes; rural physicians focused on the latter two.

Conclusions: Robust evaluation is an essential next step in determining whether the provincial privileging process and dictionaries have achieved their primary goal of improving patient safety.

The impact of the provincial privileging process and dictionaries on rural generalist practice should be thoroughly evaluated to determine whether they have improved patient care and safety.

Background

Achieving patient safety within the context of providing high-quality care is the lodestar of our health care system.[1] Although there are logical antecedents to optimizing patient care, such as robust training, use of key performance indicators, adherence to regulatory standards, and peer review and patient feedback, the role of monitoring and evaluating provider skills and competencies becomes contentious. This is due not to its lack of importance, but instead to the way in which it is integrated into larger efforts to ensure health care quality. There is an ontological divide between those who believe that provider capacity to provide quality care can be assessed through a meritocratic approach based solely on education, experience, and skills as opposed to a contextual approach that includes the influence of the practice setting, population need, and available resources. This is not an evasion of the need to ensure universal standards of quality, but is instead a recognition that an industrial approach may not meet the needs of every practice setting. Within this discussion, an essential consideration is often overlooked: what are the potential harms of instituting a meritocratic approach in settings where care providers must necessarily function in the context of uncertainty to meet patient needs?

We explored these issues as a tentative first step in understanding the perceived impact of British Columbia’s provincial privileging process and dictionaries (PPPDs) on rural practice. Specifically, we were interested in the impact of the PPPDs on rural physicians’ ability to meet the needs of their patients and the long-term implications of the PPPDs for the sustainability of rural health care delivery. Although we focused on gathering data from rural physicians, to achieve equipoise in reporting, we also included the experiences of health care administrators and provincial experts. Through this inclusive approach, we endeavored to create a platform for further investigation into the impact of the PPPDs on rural practice in BC.

In health care, the terms privileging and credentialing are often used interchangeably. Although they are related processes, they are distinct. Credentialing is the process of evaluating a provider’s background (including education, qualifications, procedural skill sets, and experience) to determine suitability for practice.[2] It usually involves submission of relevant documents to the credentialing body (in BC, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia) to determine suitability for practice. Privileging is the process of granting permission to health care providers to perform discrete procedures within a given jurisdiction or facility based on clinical skills and experiences. In BC, privileging is the responsibility of regional health authorities.[3] In short, credentialing establishes qualifications, whereas privileging establishes the specific clinical activities that can be undertaken. In this study, participants spoke to the privileging process in BC.

Although the general structure of physician privileging is relatively homogeneous across Canada, from documentation requirements to the stepwise progression of applications through governing bodies, many of the specifics are province or territory dependent. For example, in Alberta, as of July 2023, the relevant medical director is tasked with approving privileging applications to streamline the process.[4] Across Canada, the number of discrete steps in the application process ranges from a facility-only application (Alberta and Ontario) to a single province/territory-wide application that covers all facilities or regions (Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nova Scotia).[5,6] Of note, Saskatchewan’s application requirements vary: in the urban regions of Regina and Saskatoon, applications are vetted by the health region, but in rural areas, the application is facility specific. Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan have amended processes to facilitate locum applications for privileges by granting temporary privileges while awaiting formal review to negate delay to practise or by reducing the number of approvals required to grant privileges, respectively.[7,8] Other provinces require locums to apply for privileges in the same manner as other physicians, but temporary privileges are not granted while awaiting decision. Currently, BC is the only province that uses provincial privileging dictionaries. However, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta refers medical directors to BC’s PPPDs for “guidance on standard benchmarks and practice expectations.”[9] If applying for noncore privileges in the Northwest Territories, the number of times the procedure was performed in the previous 36 months and documentation demonstrating additional training are requested; however, it is not evident whether there is a threshold that providers are required to meet.[6]

Credentialing and privileging in BC

In 2014, BC undertook significant changes to the privileging of health care providers, under the provincial Privileging Standards Project. The project was developed largely in response to the misinterpretation of CT images in three regional health authorities in 2010, which precipitated an investigation by the BC Patient Safety and Quality Council (now Health Quality BC).[10] The report indicated that the previous system of self-regulation by practitioners did not ensure patient safety, which prompted the system to move to criteria-based privileging.[10] The criteria required were represented through the development of a series of specialty and subspecialty dictionaries that defined core privileges assumed to have been gained through formal training programs. Noncore privileges were those that would require additional education and training.

Although initial iterations of the dictionaries were primarily volume-based, revisions have been made to the criteria; however, the legacy of procedural volume has remained part of the criteria. Although this is appropriate for complex procedures, for which evidence shows that safety is contingent on repetition,[11] it is not as directly applicable to a generalist skill set, which by definition involves a wide scope of practice. The issue becomes more contentious when applied to rural settings, which are naturally defined by a low procedural volume, the lack of a specialist safety net, and the obligation to meet the immediate needs of the population catchment.

Unlike other jurisdictions, BC has not undertaken an in-depth evaluation of the PPPDs, with input from key partners on the metrics needed for a robust evaluation. The findings we present are not such an evaluation, but are instead a tentative first step in documenting the response to the PPPDs by rural providers, administrators, and provincial leaders to understand potential issues that require further focus.

Methods

Data were collected through open-ended qualitative research interviews to understand the experiences of rural physicians and administrators who use BC’s privileging dictionaries, as well as the impact of the dictionaries on rural practice. This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the University of British Columbia’s Behavioural Research Ethics Board (Ethics ID: H22-00756).

Setting and participants

Expert interviews were conducted with 10 participants, including practitioners in rural and subregional hospitals in BC, health administrators, and those involved in provincial health service decision making. Interviews were held via Zoom, which minimized travel-related challenges.

Data collection

Data were collected between May and August 2022. All interviews were led by the principal investigator and supported by a research assistant. Prior to the interview, participants were sent a consent form to review. Each participant was given the opportunity to ask questions before the start of the interview and provided verbal informed consent to participate. Additionally, consent for audio recording was granted for all interviews. Interviews were transcribed via the transcription feature on Zoom, thereby removing the need for external transcription. Each interview transcript was reviewed against the audio recording to ensure accuracy.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.[12] The primary coder (A.C.) listened to the interview recordings and reread the transcripts multiple times. Once familiarization with the data set was achieved, a coding framework was drafted, which outlined main ideas reported across the data set.[13] These recurring ideas (codes) were organized into a hierarchical structure, with parent codes encapsulating broader thematic concepts and child codes dividing main ideas into more specific categories. Through the codebook development process, the research team met regularly, and there was a high level of agreement within the team about the codes generated through engagement with the data set. Once the codebook was completed, it was applied to the entire data set using NVivo 12 software. To augment the reliability of the coding process, the research team continued to meet regularly to discuss codes, ensure consensus about interpretation of the data, and iteratively adjust the codebook as needed.

Upon completion of coding, the team met again to consider and name final themes. These were the overarching ideas expressed across the data set that encapsulated participants’ experiences with the PPPDs. Themes were developed inductively through primary engagement with the data set rather than derived from an external theoretical framework.

Methodological rigor

The authors practised reflexivity through the process of data collection, interpretation, analysis, and writing of results. The team engaged in critical reflection about potential biases they may have had that could have influenced their interpretation of the data set. This ongoing reflection and transparency are key to strengthening the trustworthiness and quality of the qualitative analysis.[14,15] The primary coder also engaged in persistent observation, returning repeatedly to the raw data and adjusting codes and themes as needed until the team was satisfied with the richness and depth of the analysis.[16]

Results

The Figure illustrates the thematic findings.

The Figure illustrates the thematic findings.

Rationale for and development of the PPPDs

Study participants agreed that there need to be structures in place to ensure that a high standard of patient care is delivered across the province. However, participants were divided on how useful the PPPDs were in that pursuit.

Proponents explained that the purpose of the dictionaries is not to dismantle generalist care or bar specialist procedures outside of “big city hospitals,” but rather to ensure that practitioners are safe to provide contextually appropriate care. Some participants viewed the PPPDs as an “overblown reaction” to “one or two practitioners” who were practising outside their scope. There was discussion about the effectiveness of the consultation process used with health care providers when establishing the provincial privileging process (see full report at https://med-fom-crhr.sites.olt.ubc.ca/pppd).

Advantages

The PPPDs were seen as advantageous for ensuring patient safety through mechanisms that promote surveillance, accountability, and reflection, as well as for matching qualifications with scope of practice, which together help professionalize and legitimize health care practices. Participants appreciated that the PPPDs enable physicians to assess their competencies, thereby ensuring they provide safe and appropriate care, and serve as a regulatory framework that clearly delineates qualifications, which is particularly beneficial for less-recognized specialties.

Criticisms

Criticism of the PPPDs focused on the use of procedural volume as a measure of competence, the perceived rigidity of the categories, and a lack of attention to local context, which extended to a lack of attention to the emerging realities of virtual care and the importance of team-based care. An additional thematic concern focused on the perceived bureaucratic intrusion of the PPPDs on physician practice. Additionally, participants linked the PPPDs to increased travel costs and inconvenience for patients and challenges with physician retention.

The medical literature[17-19] does not support currency (number of procedures done) as a legitimate surrogate for competency for low-acuity procedures. Furthermore, there appears to be no evidence that supports the use of numbers as a measure of outcomes for any of the procedures performed in rural BC. The use of numbers has negatively impacted both physician practices and patients’ access to care.

Lack of attention to local context

Participants noted the variability of facility and provider resources in rural communities, the extensive use of team-based care in rural hospitals, and the consequences of referring patients out of their communities for health care further reduce the validity of the numbers used in the privileging dictionaries. The issue of context has been poorly understood in the development of the provincial privileging process.

Virtual care

Participants emphasized that technological advances, such as virtual consultations, are reshaping rural health care delivery in ways not currently addressed by the PPPDs, potentially altering established standards and complicating privileging structures.

Bureaucratic intrusion

Participants reported that the privileging application process has been sufficient to cause some physicians to limit their locum practices or decline requests from other communities to help with emergency room coverages. This has resulted in preventable rural emergency room closures, together with increased risk, costs, and travel for patients.

Impact on patient care

The provincial privileging process has resulted in physicians reducing the scope of their practices, which has led to a loss of local services and increased travel for patients. Consequently, many participants expressed concerns about the quality of patient care.

Impact on recruitment and retention

Participants gave examples of colleagues who dropped procedures or walked away from work completely due to exhaustion with the system. One participant suggested that where physicians used to push back against rules that hindered their work without benefit, many now circumvent the impediments the PPPDs pose by becoming increasingly specialized or leaving rural practice. Some participants highlighted the negative psychological impact of the provincial privileging process on rural physicians, citing increased insecurity and decreased professional satisfaction.

Provider scope of practice

Participants gave concrete examples of where they had observed a diminished scope due to the dictionaries, in either their own work or their colleagues’ work. Some participants cited low procedural volume and the consequent limiting of privileges, while others pointed to exhaustion with the administrative burden of the PPPDs and gave examples of providers who let skills go to simplify their privileging process.

Suggestions moving forward

In their discussion of the best way to move forward, recognizing the importance of checks and balances to ensure patient safety and quality, participants identified potential improvements to the PPPDs focused on improving the education system or advocated for a different system entirely.

Suggestions for improvements to the PPPDs

Suggestions for improvements to the PPPDs often focused on the need for a better approach to providers who have been identified by the dictionaries as falling below a threshold for privileging. Other suggestions included the need to move away from an arbitrary number, suggesting that the dictionaries be reshaped and geared toward attitudes and behaviors rather than just procedural scope, and the need for a more central provincial application and approval process that would improve ease of practising between health regions, together with greater locum accessibility.

Education system improvements

Some participants identified the education system as a locus for important system improvements, in tandem with or in place of the PPPDs.

Alternative systems

Participants described a need for a more contextual system that is less top down and more bottom up. Many also discussed the efficacy of programs such as moreOB, in which the quality of care focus is on the team rather than a single provider. A large, overall takeaway for many participants was a concern that the current dictionaries rely on punitive measures to ensure quality of care rather than supporting providers to ensure they are working to the height of their abilities. This was seen as especially important for providers who work in rural communities and may not have easily accessible support from peers yet are crucial to maintaining access to care for local populations.

Discussion

Participants had starkly contrasting views on the effectiveness of the PPPDs in promoting patient safety and sustainability for health care providers: administrative opinions were generally positive, whereas rural health care provider opinions were predominantly critical. The divergence in perspectives highlights the administrative focus on system accountability and efficiency, often at the expense of increasing administrative burdens that detract from direct patient care for providers. Notably, the PPPDs often exacerbated bureaucratic challenges, thereby negatively impacting physician morale and suggesting a disconnect between policy implementation and the practical realities of rural health care. Rural physicians advocated for a more integrated approach to quality assurance that recognizes the unique challenges of rural settings and involves providers directly in policy formulation to mitigate unintended consequences. This call for inclusive, context-aware policymaking is crucial to avoid further disempowering those at the front line of rural health care.

Study limitations

This study provides the tentative first steps in understanding the issues and concerns with BC’s PPPDs through a rural lens. The purpose is not to present an exhaustive and comprehensive overview of the benefits and challenges, but to identify the high-level issues—both positive and negative—through the inclusion of rural physicians’ voices alongside the voices of administrators and provincial experts. Although we achieved this, the themes may not be consistent across all rural health care providers due to both the low number of participants and the likelihood that those who did participate felt passionate about the topic. This potential for response bias (and nonresponse bias) is a limitation of a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the PPPDs on rural physicians and rural health care practice, but it is not a limitation in this study, given its modest objectives.

Conclusions

Dissenting opinions were expressed by quality leaders and health care administrators compared with rural care providers: the former focused on the administrative efficiency of the PPPDs and the gap they filled in ultimately optimizing patient care; the latter focused on the challenges to rural practice that the PPPDs were seen to precipitate. Our findings are prudent first steps toward understanding the implementation of the PPPDs through a rural lens but are not a definitive assessment. A thorough evaluation of the impact of the PPPDs on rural generalist practice should be undertaken, guided by the following value propositions:

- Rural is not “small urban.”

- Collaboratively developing these metrics through a consensus-based process is an essential starting point.

- Any technological solutions should be supported and reinforced by associated changes in the culture of quality oversight and should not be seen as a discrete solution to concerns about the overarching process.

- Ongoing feedback loops should be enabled to allow clear and consistent communication from all partners about successes and challenges of the resulting process.

A robust rural evaluation that adheres to the principles noted is an essential first step in determining whether the primary goal of improving patient care and safety has been achieved through the PPPDs in BC. This consideration is particularly urgent against the backdrop of the current health human resource crisis.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge, with gratitude, the rural physicians, administrators, and provincial leaders who participated in this study. They also gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Simrat Dial in manuscript and figure preparation.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge partial funding for this work from the Rural Health Services Research Network of BC.

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed in this study are not publicly available to prevent subject identification due to the small number of participants in a localized area. The data may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

Dr Meyer supported PricewaterhouseCoopers as a consultant in preparation of its proposal to develop a new software solution for a new credentialing and privileging process in BC. His travel and accommodation for a presentation meeting in Vancouver was sponsored by PricewaterhouseCoopers. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Lacagnina S. The triple aim plus more. Am J Lifestyle Med 2018;13:42-43.

2. Patel R, Sharma S. Credentialing. StatPearls. Accessed 30 July 2024. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519504/.

3. Slater J, Block-Hansen E. Changes to medical staff privileging in British Columbia. BCMJ 2014;55:23-27.

4. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Credentialing and privileging in CPSA-accredited facilities. A guide for medical directors. May 2023. Accessed 19 April 2023. https://cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Credentialing-and-Privileging-Guide-for-Accredited-Facilities.pdf.

5. Nova Scotia Health Authority Credentialing Office. NSH application for reappointment to medical / dental staff. 2023. Accessed 19 April 2023. https://physicians.nshealth.ca/sites/default/files/2024-02/NSHA%20Reappointment%20Application%20-%202024%20V1.2.pdf.

6. Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority, Office of Medical Affairs and Credentialing. Family medicine application form. Accessed 18 September 2024. www.hss.gov.nt.ca/en/services/medical-licence/applying-first-time-medical-licence-nwt.

7. Saskatchewan Health Authority. Interim practitioner staff bylaws, 2023. Accessed 18 September 2024. www.saskhealthauthority.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/Bylaws-PSA-SHA-Interim-Practitioner-Staff.pdf.

8. Nova Scotia Health Authority. Privileges and credentials. Accessed 19 April 2023. https://physicians.nshealth.ca/topics/privileges-and-credentials.

9. College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta. Credentialing and privileging in CPSA accredited facilities. A guide for medical directors. Accessed 18 September 2024. https://cpsa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Credentialing-and-Privileging-Guide-for-Accredited-Facilities.pdf.

10. Cochrane DD. Investigation into medical imaging, credentialing and quality assurance. Phase 2 report. Vancouver: BC Patient Safety and Quality Council, 2011. Accessed 12 November 2022. www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2011/cochrane-phase2-report.pdf.

11. Levaillant M, Marcilly R, Levaillant L, et al. Assessing the hospital volume-outcome relationship in surgery: A scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2021;21:204.

12. Kiger ME, Varpio L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach 2020;42:846-854.

13. Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol 2020;18:328-352.

14. Cameron KL, McDonald CE, Allison K, et al. Acceptability of Dance PREEMIE (a Dance PaRticipation intervention for Extremely prEterm children with Motor Impairment at prEschool age) from the perspectives of families and dancer teachers: A reflexive thematic analysis. Physiother Theory Pract 2023;39:1224-1236.

15. Yeh M-C, Lau W, Chen S, et al. Adaptation of diabetes prevention program for Chinese Americans—A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1325.

16. Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract 2018;24:120-124.

17. Kornelsen J, McCartney K, Williams K. Centralized or decentralized perinatal surgical care for rural women: A realist review of the evidence on safety. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:381.

18. Johnston CS, Klein MC, Iglesias S, et al. Competency in rural practice. Can J Rural Med 2014;19:43-46.

19. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, College of Family Physicians of Canada, Society of Rural Physicians of Canada. Number of births to maintain competence. Can Fam Physician 2002;48:751–758.

Dr Kornelsen is the co-director of the Centre for Rural Health Research and an associate professor in the University of British Columbia’s Department of Family Practice. For 15 years, she has focused on creating and sharing comprehensive evidence to support rural health planning, particularly regarding maternity and surgical care. Ms Cameron is a research coordinator at the Centre for Rural Health Research. She is passionate about research that bridges the epistemological divide between patients and academic researchers through co-productive research methods. Her work focuses on rural maternity care, community participation in health research, and sustainable rural health systems. Ms Rutherford is an undergraduate medical student in UBC’s Southern Medical Program. Mr Dresselhuis is an undergraduate medical student in UBC’s Island Medical Program. Dr Johnston is a clinical associate professor in UBC’s Department of Family Practice and a site visitor for the UBC Postgraduate Medical Education program. He has been a rural family practitioner for the past 33 years and has published research pertaining to rural health care. Dr Meyer is a distinguished family physician recognized for his expertise in primary care and health systems improvement, particularly in rural Canadian communities. He holds positions at the Rural Coordination Centre of BC and is a clinical associate professor at UBC and the University of Northern British Columbia.

Corresponding author: Dr Jude Kornelsen, jude.kornelsen@familymed.ubc.ca.