Original Research

Impact of the family physician shortage on BC specialists’ health and well-being

ABSTRACT

Background: Little is known about the impact the shortage of primary care physicians has on specialists who are caring for patients who do not have a family physician.

Methods: This qualitative study involved semi-structured interviews with 37 specialists in Victoria, British Columbia; an additional 21 specialists provided written comments anonymously in an online forum. Participants were asked to describe the impact the shortage of primary care physicians has on their patient profile, clinical workflows, and work volumes.

Results: Participants reported an increase in the number of patients who do not have a primary care physician. This has affected specialists’ ability to discharge patients, which has resulted in longer wait lists and a greater work burden. Additionally, patients who do not have a family physician seek care from specialists that is beyond the scope they can provide. Participants also reported a decline in the quality of their professional and personal relationships and an increase in moral distress; some stated they were delaying retirement or leaving the workforce early and were concerned about the erosion of their skills and the ability to take sick time or extended leave.

Conclusions: The shortage of primary care physicians has ripple effects on other levels of care. This exacerbates existing issues related to labor shortages and burnout for specialists practising in BC.

Specialist physicians have experienced negative effects on their health, career plans and trajectory, and professional and personal relationships due to the family physician shortage.

Background

The ongoing shortage of family physicians who provide primary care is well documented, and concerns about the implications for patients have become increasingly urgent.[1-3] However, little attention has been paid to how this shortage affects specialist physicians. Specialist and primary care services are complexly intertwined. Specialists rely on family physicians to appropriately refer patients and to continue care after specialized services conclude. Specialists are already facing high levels of burnout and dissatisfaction with work–life balance, which has intensified due to the COVID-19 crisis.[4-6] The family physician shortage exacerbates existing capacity strains, especially when specialists find the care they can provide is less effective than it ideally would be.[7]

When specialists experience moral distress, they are more likely to leave medicine, which erodes the robustness of the physician workforce.[8,9] They are also more likely to disengage from patient-centred care, such as by avoiding or abbreviating tasks related to patient communication.[10] It is only through understanding the specific impacts of the family physician shortage on specialists that this negative spiral can be mitigated. We describe changes in the scope and volume of specialist work due to the increase in the number of patients who do not have a family physician and link these changes to outcomes for specialists’ relationships, career experiences, and personal and familial health.

Methods

This research was conducted in Victoria, British Columbia, between February and May 2022. Participants were recruited via postings in the local Medical Staff Association newsletter, which has an estimated readership of 500 physicians. The sample was self-selected. Ethical considerations were part of the funding approval process through the Medical Staff Association’s review of the proposed project.

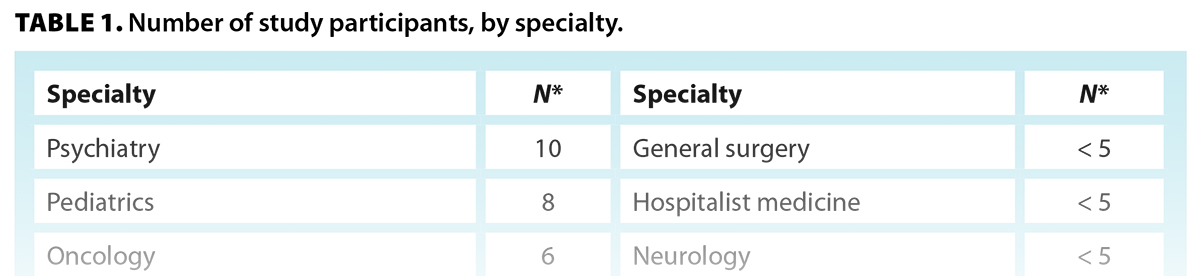

Two methods were used: qualitative semi-structured interviews (37 individuals) and an anonymous online forum (21 individuals, likely unique from those who participated in the interviews). A wide range of specialties (18) were represented, but there was clustering in pediatrics, psychiatry, and oncology, all of which have frequent interactions with primary care [Table 1].

In both methods, participants were asked how the family physician shortage has affected their patients, practice, and well-being. They were also asked to estimate the proportion of their patients who did not have a family physician. The interview questions and forum prompts are provided in the Box.

Interviews were transcribed. All co-authors reviewed the first 10 interviews individually and identified initial themes, which were then discussed and finalized before one co-author analyzed the remainder of the responses. There were few discrepancies in coding, and they were resolved through consensus. Ensuring intercoder agreement enhanced the trustworthiness of the thematic coding. Thematic analysis was guided not by a priori theorization but rather by a pragmatic, descriptive approach.

As with all qualitative research, researcher characteristics inform interpretation. In this case, researcher characteristics were diverse and brought unique perspectives to the project. The team consisted of a medical student, a family physician, and an applied sociologist, each of whom had their areas of expertise and “blind spots” that could be addressed by the others. This allowed for a full exploration of themes in the data as they emerged.

Results

All participants indicated that the proportion of their patients who did not have a family physician was increasing over time. Self-reported estimates ranged from 10% to 65%, with a median of 50%.

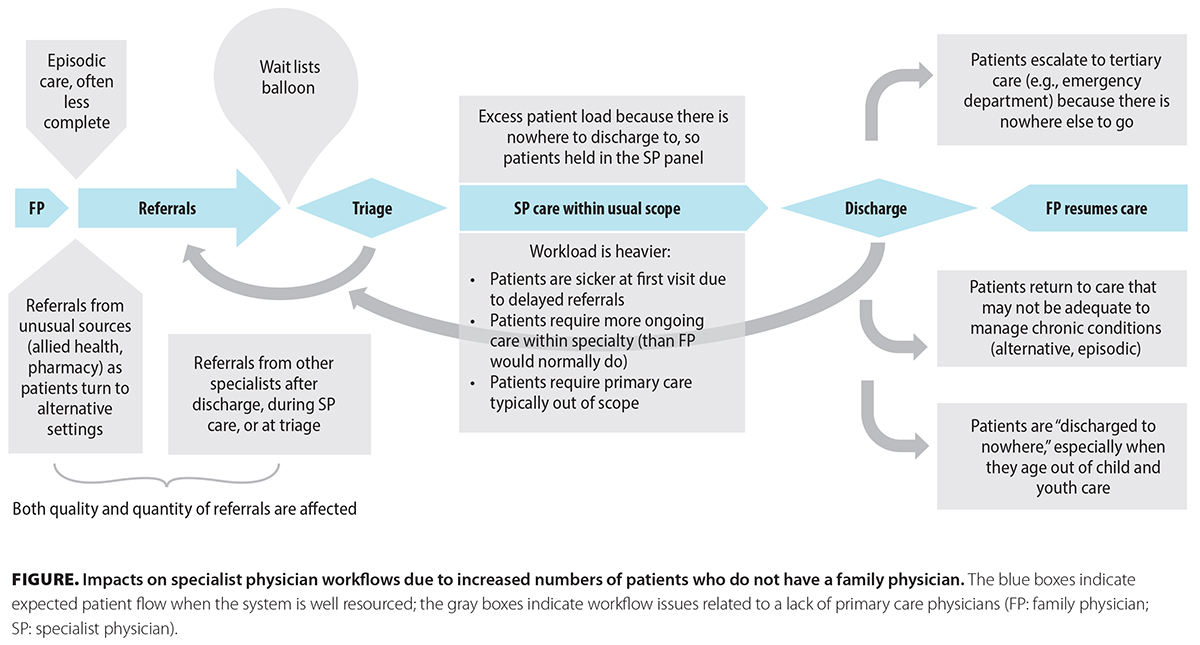

Specialists reported that patients who did not have a family physician were significantly further along in their disease state at initial referral than those who had a family doctor. In addition, specialists were unable to discharge patients who needed ongoing monitoring but not ongoing specialized services, and they had to provide a greater proportion of primary care within their specialty than they had previously done. The Figure represents the scope and workload pressures that participants identified.

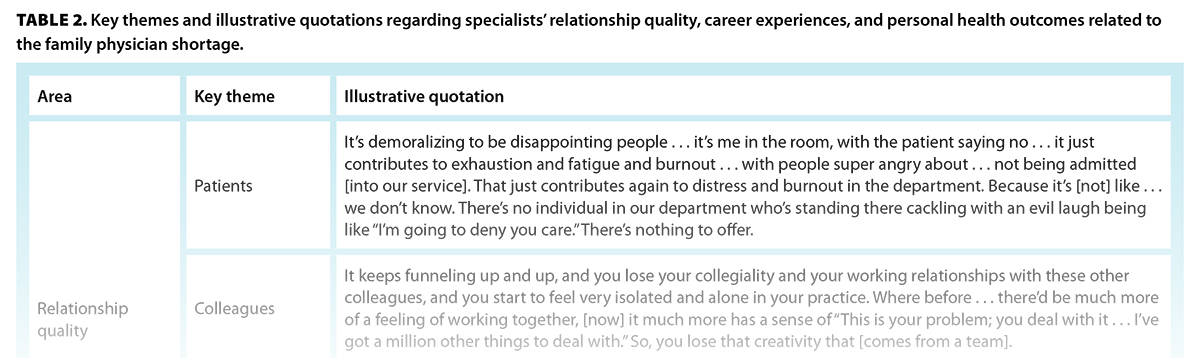

As a consequence of these pressures, participants reported effects on their well-being in terms of relationship quality, career experiences, and personal health [Table 2]. These were not mutually exclusive; they exacerbated one other. First, the quality of their relationships with patients, colleagues, and loved ones had declined. In terms of career experiences, specialists were reducing the scope of services offered, delaying retirement, or exiting the workforce early. They also worried about the possible erosion of their specialized skills. Finally, they experienced health impacts, including a lack of access to primary care for themselves, an inability to take time off work for illness or long-term absences such as parental leave, and an increasing sense of moral distress and injury.

Discussion

The family physician shortage has led to bottlenecks in discharging patients, ballooning wait lists, and a heavier and more complex workload. This results in negative outcomes for specialists individually, including declining quality of relationships with others, both personal and professional; effects on their career plans and trajectory; and negative health outcomes, particularly moral distress and injury. Because many specialties also face physician shortages, the lack of primary care physicians may exacerbate existing workforce pressures in specialist services.

Despite the interconnectedness of the health care system and the general awareness of the family physician shortage, few studies have examined the ripple effects on specialists. However, heavier specialist workloads have been shown to be associated with more errors.[11] Lack of primary care capacity has been identified as a barrier to implementing care models that could improve the sustainability of the specialist workforce.[12] In addition, physicians tend to respond to resource limitations by “going above and beyond the call of duty,” which puts them at further risk of burnout.[13] The participants in this study work in an interdependent health system; therefore, the lack of family physicians has created ongoing and increasing challenges in their work and personal lives.

Study limitations

This study was limited by the self-selection of participants, who may have chosen to participate specifically because they were experiencing negative impacts related to the family physician shortage. Therefore, the findings cannot be generalized to the specialist population. Because this research is qualitative, a direct causal relationship between the family physician shortage and participants’ experiences of negative outcomes cannot be proven. The participants acknowledged that the family physician shortage was not the only stressor impacting their lives. Finally, a student researcher conducted the interviews. Some participants expressed concern that sharing their experiences could “scare her away” from medicine; as a result, they may have tempered their comments.

Conclusions

This study illustrates the complex interdependencies between family physicians and specialists and provides insight into the unique experiences of physicians who are providing specialist care today. It is clear that the family physician shortage is having far-reaching consequences for patients. Equally clear is that the shortage is also impacting other health care professionals by compounding the capacity strains they were already experiencing. Without sustained attention to both the labor needs and current impacts of health care shortages, the system will continue to operate in a fragmented, suboptimal way, putting patients—and physicians—at continued risk.

Competing interests

None declared.

BOX. Interview and online forum questions

- Interviews: The following questions were included in the interview guide. The interviewer had leeway to follow the course of the conversation with additional questions as seemed appropriate.

- What was it that caught your eye and made you respond to our project?

- Can you share some examples or stories about patients you have treated who do not have a family physician and how this has impacted their care?

- Have you found that the family physician shortage has impacted your practice? For instance:

- How has your scope of practice changed?

- How has the morbidity or mortality of your patients differed?

- How have transitions of care been affected?

- Online forum: Because the online forum was a more passive environment where no follow-up was possible, a more general prompt was provided in the hopes of eliciting a broad range of responses:

- How has the BC primary care crisis affected your practice?

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med 2015;13:107-114.

2. Kuusio H, Lämsä R, Aalto A-M, et al. Inflows of foreign-born physicians and their access to employment and work experiences in health care in Finland: Qualitative and quantitative study. Hum Resour Health 2014;12:41.

3. Seleq S, Jo E, Poole P, et al. The employment gap: The relationship between medical student career choices and the future needs of the New Zealand medical workforce. N Z Med J 2019;132:52-59.

4. Kang J, Choi EK, Seo M, et al. Care for critically and terminally ill patients and moral distress of physicians and nurses in tertiary hospitals in South Korea: A qualitative study. PLoS One 2021;16:e0260343.

5. Kok N, van Gurp J, Teerenstra S, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 immediately increases burnout symptoms in ICU professionals: A longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med 2021;49:419-427.

6. Burns KEA, Fox-Robichaud A, Lorens E, Martin CM. Gender differences in career satisfaction, moral distress, and incivility: A national, cross-sectional survey of Canadian critical care physicians. Can J Anaesth 2019;66:503-511.

7. Austin CL, Saylor R, Finley PJ. Moral distress in physicians and nurses: Impact on professional quality of life and turnover. Psychol Trauma 2017;9:399-406.

8. Mackel CE, Alterman RL, Buss MK, et al. Moral distress and moral injury among attending neurosurgeons: A national survey. Neurosurgery 2022;91:59-65.

9. Dodek PM, Cheung EO, Burns KEA, et al. Moral distress and other wellness measures in Canadian critical care physicians. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021;18:1343-1351.

10. Lamiani G, Biscardi D, Meyer EC, et al. Moral distress trajectories of physicians 1 year after the COVID-19 outbreak: A grounded theory study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:13367.

11. Tariq MB, Meier T, Suh JH, et al. Departmental workload and physician errors in radiation oncology. J Patient Saf 2020;16:e131-e135.

12. Neuman HB, Jacobs EA, Steffens NM, et al. Oncologists’ perceived barriers to an expanded role for primary care in breast cancer survivorship care. Cancer Med 2016;5:2198-2204.

13. Sukhera J, Kulkarni C, Taylor T. Structural distress: Experiences of moral distress related to structural stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Med Educ 2021;10:222-229.

Dr Mason is a family physician and board director of the Victoria Division of Family Practice. Dr Atwood is Director, care innovations, for the Victoria Division of Family Practice. Ms Hodgins is a student in the Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia.