Getting SAVy about sexually transmitted infection testing

ABSTRACT

Background: Self-administered vaginal swabs became available at the Island Health outpatient lab in Campbell River and at labs throughout northern Vancouver Island in February 2021. This project aimed to increase the use of the swabs to improve access to testing for sexually transmitted infections.

Methods: Clinicians and lab staff at Island Health lab collection sites on northern Vancouver Island were surveyed to gauge their understanding of self-administered vaginal swabs. Information sessions were provided to enhance their knowledge. Patient satisfaction surveys were also conducted.

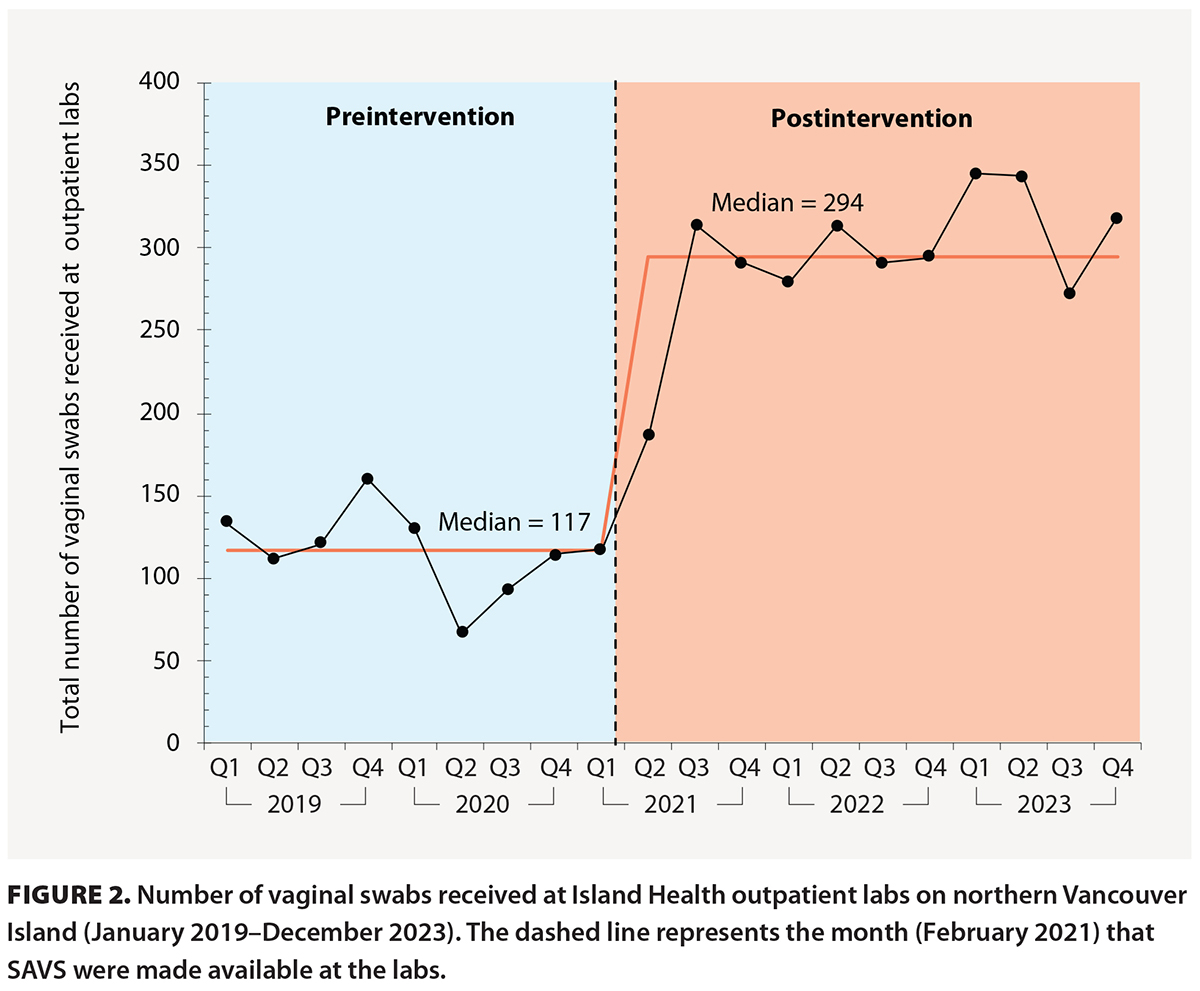

Results: At baseline, a median of 117 swabs per quarter were returned to Island Health lab collection sites on northern Vancouver Island. After the swabs became available, the median increased to a peak of 294 per quarter. Knowledge about the swabs among lab staff and clinicians increased from 33% preintervention to 100% postintervention. Patients preferred the swabs over other testing methods.

Conclusions: Improving access to and providing education about self-administered vaginal swabs led to increased sexually transmitted infection testing at Island Health labs on northern Vancouver Island.

Providing access to self-administered vaginal swabs and informing clinicians and patients about their use led to increased testing for sexually transmitted infections in Island Health.

Background

Testing for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in individuals with female anatomy has historically taken place in a clinician’s office using endocervical swabs, often in conjunction with a Pap test. However, the accuracy of using self-administered vaginal swabs (SAVS) to detect chlamydia and gonorrhea is equal to or greater than that of clinician-collected endocervical swabs and first-catch urine tests;[1-4] the latter may miss up to 10% of chlamydia infections in patients with female anatomy (though it remains the gold standard for STI testing in patients with male anatomy).[5-7] BD ProbeTec CT/GC Qx vaginal swabs (the type used in Island Health) have a sensitivity of 99.3% and 99.5% and a specificity of 98.6% and 99.8% in detecting chlamydia and gonorrhea, respectively.[8]

SAVS also have a lower lifetime cost, because visits to health professionals are reduced.[9] High levels of patient satisfaction with SAVS have also been reported.[10,11] Their use is more desirable among those with aversions to clinician-collected sampling for personal, religious, or cultural reasons, or due to gender identity, ability, or trauma triggers;[11,12] the swabs are also easier to use than having a pelvic examination performed with a vaginal speculum. The use of SAVS increases accessibility to STI testing for patients with limited access to primary care, such as those in rural locations,[11] and increases the chance that routine tests will be completed.[13]

SAVS have been available in Canada since at least 2003.[4] They have been available in sexual health clinics and clinician offices on northern Vancouver Island for some time, but prior to February 2021, they were not available at the Island Health outpatient lab in Campbell River—the largest community on northern Vancouver Island and the referral centre for several outlying communities—or in other northern Vancouver Island sites. As a result, patients could self-collect a vaginal specimen only at a clinician’s office, even if they had already had a virtual or telehealth visit with their clinician. In contrast, a clinic visit is not required for first-catch urine testing; the requisition can be sent directly to the lab, where the patient provides the sample. Requisitions for SAVS can either be sent directly to the lab or be given to the patient. Patients can collect the specimen at the lab or take the swab home and then return the sample to the lab [Figure 1].

SAVS have been available in Canada since at least 2003.[4] They have been available in sexual health clinics and clinician offices on northern Vancouver Island for some time, but prior to February 2021, they were not available at the Island Health outpatient lab in Campbell River—the largest community on northern Vancouver Island and the referral centre for several outlying communities—or in other northern Vancouver Island sites. As a result, patients could self-collect a vaginal specimen only at a clinician’s office, even if they had already had a virtual or telehealth visit with their clinician. In contrast, a clinic visit is not required for first-catch urine testing; the requisition can be sent directly to the lab, where the patient provides the sample. Requisitions for SAVS can either be sent directly to the lab or be given to the patient. Patients can collect the specimen at the lab or take the swab home and then return the sample to the lab [Figure 1].

During the pandemic, clinicians were unable to conduct STI testing during clinic closures due to COVID-19 outbreaks. Even though SAVS were available and the patient did not need a clinician to collect a vaginal sample, the Island Health outpatient labs on northern Vancouver Island did not have a protocol for patients to self-collect a sample—only the less sensitive first-catch urine testing was available. This quality improvement project was conceived to bridge this gap in care. The aim was to increase the number of SAVS processed through the Island Health outpatient labs so that STI testing could be conducted in a timely, efficient, accessible, and cost-effective manner.

Methods

The project was submitted to the Island Health Quality Improvement Registry. Because it was a quality improvement project, it was deemed exempt from a formal research ethics board review.

The intervention took place within seven Island Health lab collection sites on northern Vancouver Island: Campbell River, Quadra Island, Port Hardy, Alert Bay, Port McNeill, Port Alice, and Gold River. All SAVS specimens were processed in a central Island Health site in Victoria.

The number of vaginal swabs received quarterly at the Island Health outpatient labs was analyzed from 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2023.

Clinicians and lab staff were surveyed to gauge their understanding of the accuracy and acceptability of SAVS. The survey link was sent via email. The results were used to develop information sessions to raise awareness of the recent availability of SAVS at the labs. The sessions were conducted in April and May 2021, and a follow-up survey was sent by email.

Patient surveys were also made available in specimen collection areas via posters with a QR code. All survey responses were voluntary and anonymous and were collected using SurveyMonkey.

The results of the clinician and lab staff surveys and patient satisfaction surveys were reviewed by the principal investigator.

Results

The number of vaginal swabs received at the Island Health outpatient labs on northern Vancouver Island increased from a median of 117 per quarter from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2021 to 184 in the first 3 months after they were made available. A further increase to a median of 294 per quarter occurred from 1 July 2021 to 31 December 2023 [Figure 2]. The number of swabs received remained high, even though no further clinician education or new public health information was provided.

The number of vaginal swabs received at the Island Health outpatient labs on northern Vancouver Island increased from a median of 117 per quarter from 1 January 2019 to 31 March 2021 to 184 in the first 3 months after they were made available. A further increase to a median of 294 per quarter occurred from 1 July 2021 to 31 December 2023 [Figure 2]. The number of swabs received remained high, even though no further clinician education or new public health information was provided.

In initial surveys of lab staff (n = 9), 33% were familiar with SAVS, and 12.5% believed that SAVS were as accurate as clinician-collected specimens. The postintervention surveys (n = 5) indicated that knowledge about SAVS had increased: all respondents reported familiarity with their use.

Patient surveys (n = 5) indicated that patients preferred SAVS over other STI testing methods. All respondents reported that the collection instructions were easy to understand and that self-collection of samples was easy.

Discussion

Having SAVS available at the Island Health outpatient labs led to an increase in the number of STI tests conducted. This is particularly relevant following a change to the BC Cancer Cervical Cancer Screening Program that has resulted in fewer patients having a clinician-collected cervical screen, which is when clinicians commonly conduct STI testing.

Increased testing and identification of STIs leads to timelier and improved follow-up and treatment,[11,14] which reduces the risk of complications and the spread of infection.[11]

The use of SAVS has also led to a significant increase in rescreening and follow-up compared with clinician-collected specimens,[15] and patients who used SAVS said they would routinely self-test if SAVS were widely available.[16] Barriers to STI testing in clinical settings could be alleviated by making SAVS available at testing labs and through mail-in services and remote outreach programs.[7]

The BCCDC operates the GetCheckedOnline program, with testing available at 17 LifeLabs locations across BC.[17] An individual can register online, print a lab form, present it at a participating lab, get tested at the lab, and then get the results online.[17] BCCDC clinics in Fraser Health and Vancouver Coastal Health also offer SAVS through the SmartSexResource.[18] However, access to SAVS is still limited. Northern Health and Interior Health offer SAVS at clinics but do not provide them at testing labs.[18-20] Additionally, in some communities, it may be difficult to access a clinician to receive STI testing (a laboratory requisition is currently required for testing to be done at the Island Health outpatient labs). Therefore, implementation of SAVS programs and education about SAVS would prove useful [Figure 3]. Further research could examine the possibility of making SAVS available in pharmacies to improve accessibility and provide effective testing and treatment.[21]

The BCCDC operates the GetCheckedOnline program, with testing available at 17 LifeLabs locations across BC.[17] An individual can register online, print a lab form, present it at a participating lab, get tested at the lab, and then get the results online.[17] BCCDC clinics in Fraser Health and Vancouver Coastal Health also offer SAVS through the SmartSexResource.[18] However, access to SAVS is still limited. Northern Health and Interior Health offer SAVS at clinics but do not provide them at testing labs.[18-20] Additionally, in some communities, it may be difficult to access a clinician to receive STI testing (a laboratory requisition is currently required for testing to be done at the Island Health outpatient labs). Therefore, implementation of SAVS programs and education about SAVS would prove useful [Figure 3]. Further research could examine the possibility of making SAVS available in pharmacies to improve accessibility and provide effective testing and treatment.[21]

Study limitations

It was impossible to know how many swabs were being collected at labs versus clinician offices. However, this is likely of limited significance. The increase in the use of SAVS may have been due to increased access to care as COVID restrictions to in-person care were lifting.

We did not determine whether a positive swab for chlamydia or gonorrhea led to follow-up treatment. However, in BC, chlamydia and gonorrhea are reportable STIs, and the ordering clinician is responsible for follow-up.

Conclusions

Improving access to and providing education about SAVS led to increased STI testing at Island Health labs on northern Vancouver Island. The acceptability of SAVS among patients made them the easier option for STI testing, and ordering tests was easier because the clinician could order them during a virtual visit.

Other health authorities and private labs should consider a similar expansion of services to meet the needs of patients. First-catch urine testing, the gold standard for STI testing in those with male anatomy, is widely available at labs in BC. Making SAVS equally widely available for those with female anatomy would improve the equity of health services.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by the Campbell River Medical Staff Engagement Initiative Society, which receives Facility Engagement funding from the Specialist Services Committee.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Stewart CMW, Schoeman SA, Booth RA, et al. Assessment of self taken swabs versus clinician taken swab cultures for diagnosing gonorrhoea in women: Single centre, diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ 2012;345:e8107. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8107.

2. Schoeman SA, Stewart CMW, Booth RA, et al. Assessment of best single sample for finding chlamydia in women with and without symptoms: A diagnostic test study. BMJ 2012;345:e8013. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e8013.

3. Korownyk C, Kraut RY, Kolber MR. Vaginal self-swabs for chlamydia and gonorrhea. Can Fam Physician 2018;64:448.

4. Richardson E, Sellors JW, Mackinnon S, et al. Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis infections and specimen collection preference among women, using self-collected vaginal swabs in community settings. Sex Transm Dis 2003;30:880-885. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.OLQ.0000091142.68884.2A.

5. Schachter J, Chernesky MA, Willis DE, et al. Vaginal swabs are the specimens of choice when screening for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Results from a multicenter evaluation of the APTIMA assays for both infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:725-728. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000190092.59482.96.

6. Skidmore S, Horner P, Herring A, et al. Vulvovaginal-swab or first-catch urine specimen to detect Chlamydia trachomatis in women in a community setting? J Clin Microbiol 2006;44:4389-4394. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01060-06.

7. Lunny C, Taylor D, Hoang L, et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected sampling for chlamydia and gonorrhea screening: A systemic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132776. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132776.

8. Kawa D, Kostiha B, Yu JH, LeJeune M. Elevating the standard of care for STIs: The BD MAX™ CT/GC/TV assay. Accessed 1 March 2025. https://moleculardiagnostics.bd.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/CT-GC-TV-Whitepaper.pdf.

9. Taylor D, Lunny C, Wong T, et al. Self-collected versus clinician-collected sampling for sexually transmitted infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst Rev 2013;2:93. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-2-93.

10. Chernesky MA, Hook EW 3rd, Martin DH, et al. Women find it easy and prefer to collect their own vaginal swabs to diagnose Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections. Sex Transm Dis 2005;32:729-733. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000190057.61633.8d.

11. Fielder RL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Acceptability of sexually transmitted infection testing using self-collected vaginal swabs among college women. J Am Coll Health 2013;61:46-53.

12. Doleeb Z, Tesfaye M, Selk A, et al. The pandemic and cervical cancer screening: Is it finally time to adopt HPV self-swabbing tests in Canada? Can Fam Physician 2022;68:90-92. https://doi.org/10.46747/cfp.680290.

13. Wiesenfeld HC. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis infections in women. N Engl J Med 2017;376:765-773. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1412935.

14. Gaydos CA, Rizzo-Price PA, Barnes M, et al. The use of focus groups to design an internet-based program for chlamydia screening with self-administered vaginal swabs: What women want. Sex Health 2006;3:209-215.

15. Xu F, Stoner BP, Taylor SN, et al. Use of home-obtained vaginal swabs to facilitate rescreening for Chlamydia trachomatis infections: Two randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:231-239.

16. Wiesenfeld HC, Lowry DL, Heine RP, et al. Self-collection of vaginal swabs for the detection of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis: Opportunity to encourage sexually transmitted disease testing among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis 2001;28:321-325. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007435-200106000-00003.

17. BC Centre for Disease Control. GetCheckedOnline. Accessed 19 November 2024. https://getcheckedonline.com/Pages/default.aspx.

18. BC Centre for Disease Control. Sexually transmitted infections clinics. Accessed 8 November 2024. www.bccdc.ca/our-services/our-clinics/sexually-transmitted-infections-clinics.

19. Interior Health. Patient collection instructions. Accessed 8 November 2024. www.interiorhealth.ca/sites/default/files/PDFS/patient-collection-instructions.pdf.

20. Northern Health. Vaginal self-collections for STI testing and collection containers for STI testing. 19 July 2018. Accessed 8 November 2024. https://physicians.northernhealth.ca/sites/physicians/files/news/documents/2018/STI-testing-vaginal-self-collection-update.pdf.

21. Gaydos CA, Barnes M, Holden J, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of recruiting women to collect a self-administered vaginal swab at a pharmacy clinic for sexually transmissible infection screening. Sex Health 2020;17:392-394. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH20077.

Dr Kask is a clinical instructor in the Department of Family Practice at the University of British Columbia and a locum physician based in Campbell River. Ms Nadalini is an undergraduate student in health sciences at Simon Fraser University and a pharmacy assistant at Burnaby Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Jennifer Kask, jennifer.kask@islandhealth.ca.