Original Research

Explaining the gender pay gap: Lessons from rheumatology

ABSTRACT

Background: In British Columbia, based on Medical Services Commission reports, male rheumatologists earn on average 31.2% more than female rheumatologists. The reasons for this disparity are not completely understood.

Methods: The Department of Medicine Rheumatology Equity Committee at the University of British Columbia developed a survey that the BC Society of Rheumatologists (BCSR) distributed to its members. Survey questions included domains such as demographics, career stage, remuneration, time allocation, work hours, duration of consult and follow-up appointments, hours spent on indirect care, and patient population.

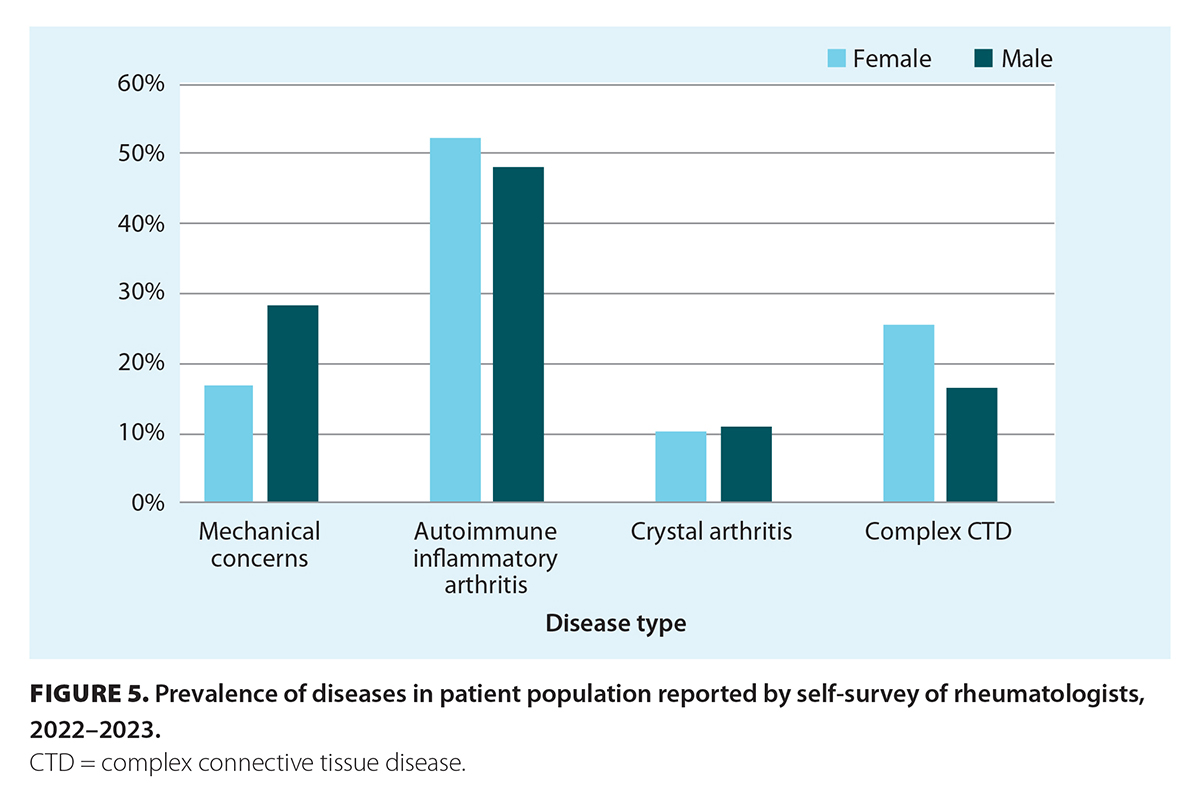

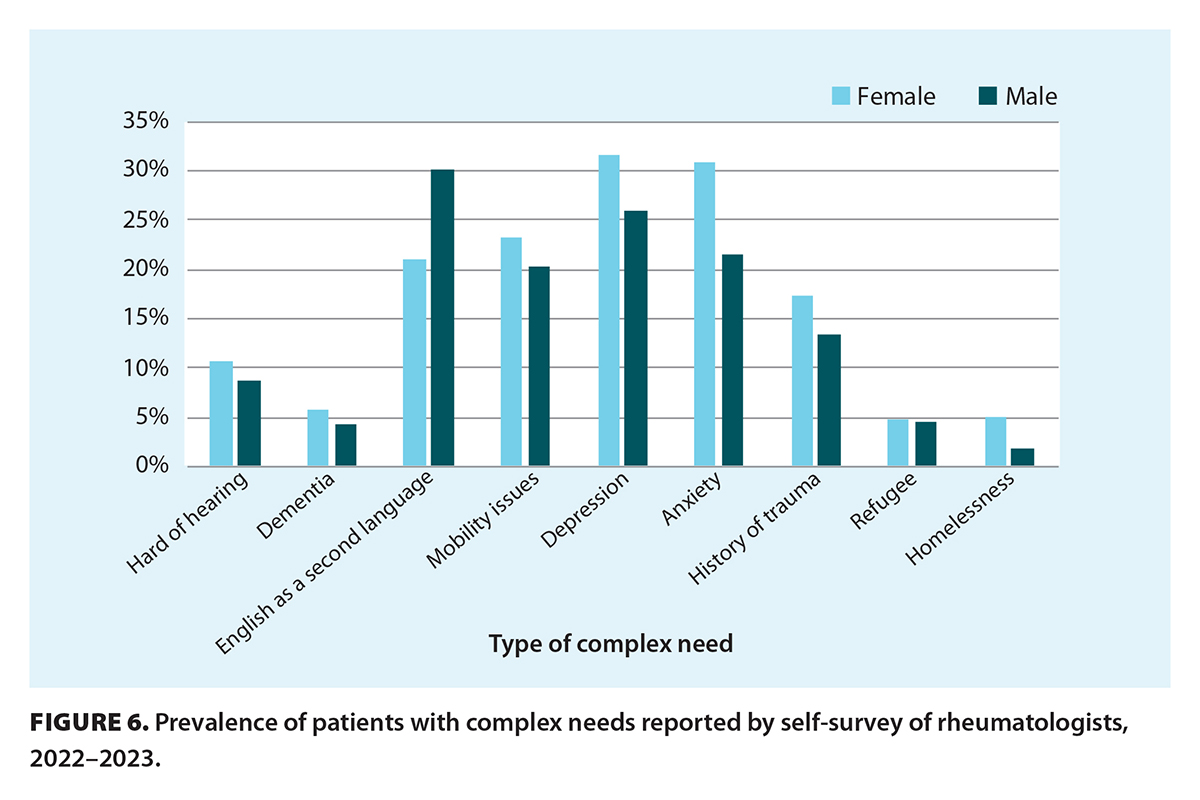

Results: Forty-nine rheumatologists (67% of BCSR members) responded. Women and men worked the same number of hours per week (42.5 and 42.6 hours, respectively). However, 71% of women earned less than $400 000 annually, compared with 33.5% of men. Women spent longer on an initial consult (50.4 minutes versus 40.8 minutes for men) and had more patients with complex connective tissue disease and fewer with mechanical concerns than did men.

Conclusions: There are significant differences in the way that female and male rheumatologists practise. Changing time-based billing codes for complex initial consultations may be one way to address these disparities.

Remuneration models should provide equitable payment based on the different ways female and male physicians practise medicine.

Background

In Canada, many physicians work under a fee-for-service model, in which a physician is remunerated a predetermined amount for a rendered medical service.[1] It would, therefore, be presumed that this payment model entails equitable payment, given the fee codes are irrespective of a physician’s gender, race, or years in practice. With the same medical training and qualifications, physicians identifying as women or men would be expected to provide the same number and quality of medical visits. However, in Canada, gender pay gaps persist universally across all specialties,[2] despite a shift in gender distribution of the medical workforce with increasing numbers of female physicians, a phenomenon termed as “feminization” of the workforce.[3] This is no exception in rheumatology. The number of women accounted for less than one-third of rheumatologists in Canada in 1995 but reached parity in 2015, and their numbers have been increasing since.[2]

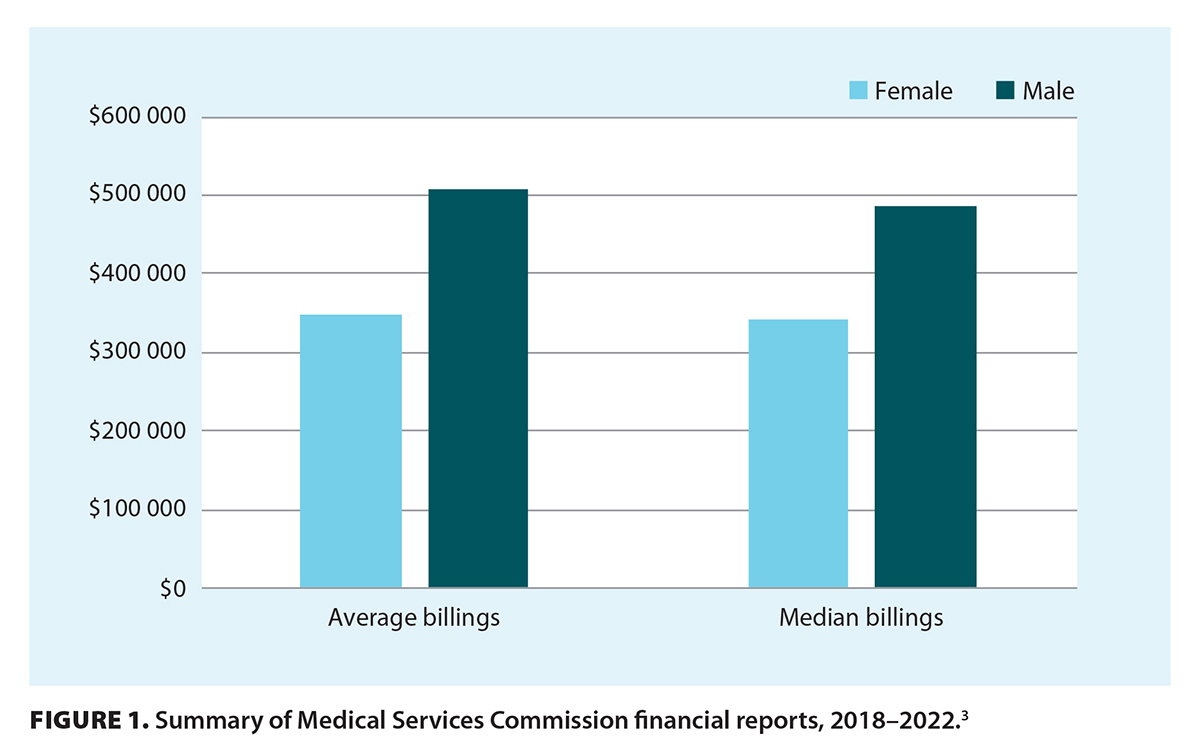

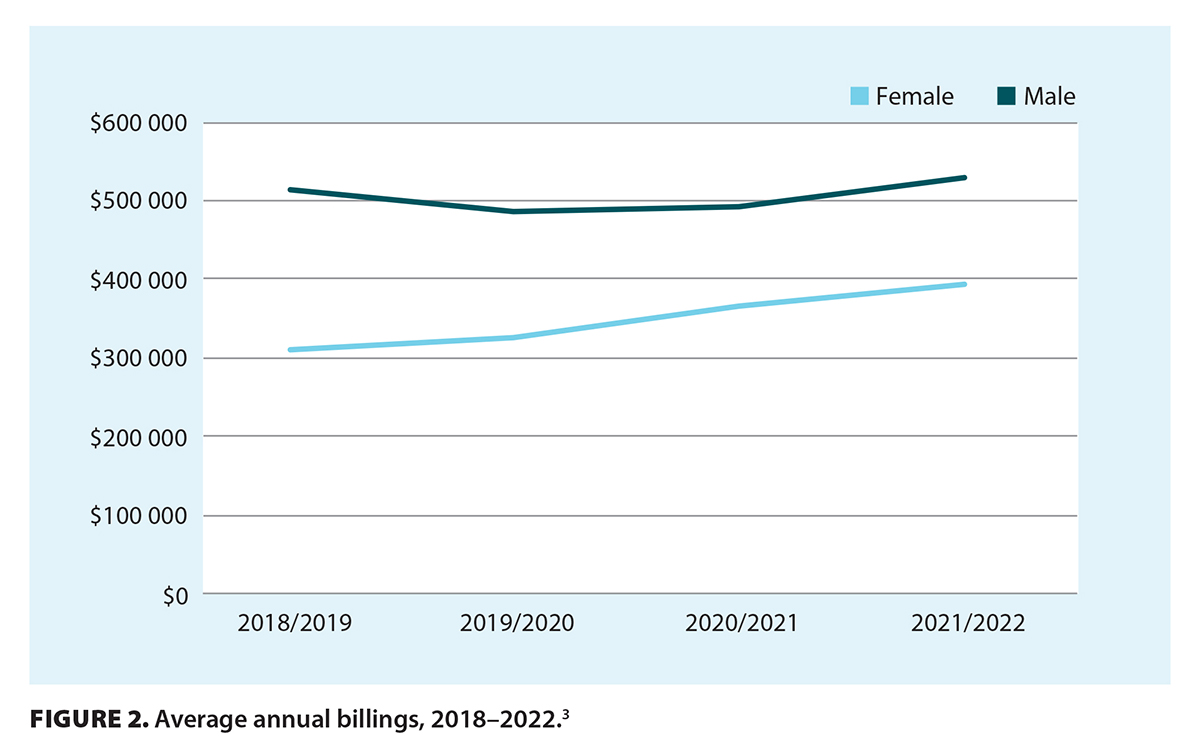

In Ontario, the gender income gap for rheumatologists equated to a 35% difference in favor of men for gross fee-for-service payments in 2016.[2] In British Columbia, the Medical Services Commission of the Ministry of Health publishes a public online financial statement that summarizes the fee-for-service payments made to all physicians. Between 2018 and 2022, female rheumatologists earned $348 406 on average, whereas male rheumatologists earned $506 238 on average [Figure 1; Figure 2]. This equates to a gender income gap of 31.2% in favor of men for gross fee-for-service payments. There was also a 40.6% difference in the average gross billings of the highest-earning woman (average $799 811) compared with the highest-earning man (average $1 347 055) from 2018 to 2022.[4]

|

|

Women with young children and those early in their career are more likely to work part-time,[5,6] though after age 38, the number of hours female practitioners work increases to prior levels (before bearing children).[7] Various other factors also contribute to pay disparities, including systemic bias in medical school,[8,9] hiring practices,[10] promotions,[11] clinical care arrangements, and fee schedules;[2] however, none of them are completely understood or have been fully examined, particularly in our local setting. The Department of Medicine Rheumatology Equity Committee at the University of British Columbia was created as a subcommittee within the BC Society of Rheumatologists (BCSR) to examine these factors.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of rheumatologists across BC. The survey questions included domains such as demographics, career stage, remuneration, time allocation, work hours, working with trainees, duration of consult and follow-up appointments, hours spent on indirect care, patient population, and physician roles outside of medicine (e.g., caregiver for children). The questions were created and voted on by the Department of Medicine Rheumatology Equity Committee. For the purposes of this study, gender was referenced in a binary fashion, though we acknowledge that further studies need to include nonbinary gender identification among physicians.

We sent out an electronic survey using the University of British Columbia Qualtrics website as a survey and data storage platform. The BCSR distributed the survey to its mailing list of rheumatologists, approximately 73 members who were registered and actively practising in 2022. The survey was available for 1 month, from July to August 2023. All responses were anonymized. The results were analyzed using descriptive statistics with examination of means, proportions, frequencies, and standard deviations. Unpaired t tests and linear regression models on R were conducted, using an alpha significance level of < 0.05. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board.

We focused on adult rheumatologists because they are compensated via the fee-for-service model in BC. We did not survey academic pediatric rheumatologists because their remuneration models are different.

Results

Forty-nine rheumatologists (67% of active BCSR members) responded to the survey: 22 men (59% of male BCSR members) and 27 women (75% of female BCSR members). Overall, a greater proportion of male rheumatologists had been in practice for more than 20 years (43%) compared with female rheumatologists (25%).

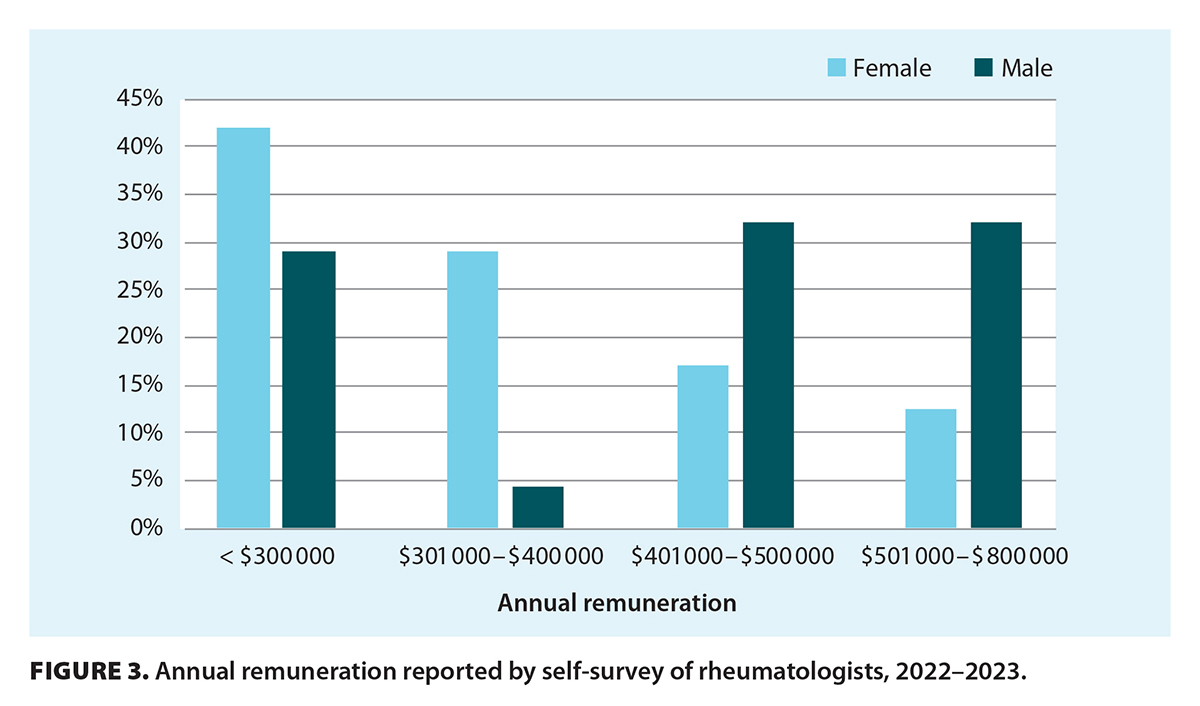

Self-reported annual remuneration indicated that in 2023, 42.0% of female rheumatologists earned less than $300 000 annually, 29.0% earned $301 000 to $400 000, 17.0% earned $401 000 to $500 000, and 12.5% earned $501 000 to $800 000 [Figure 3]. In comparison, 29.0% of male rheumatologists earned less than $300 000 annually, 4.5% earned $301 000 to $400 000, 32.0% earned $401 000 to $500 000, and 32.0% earned $501 000 to $800 000 [Figure 3].

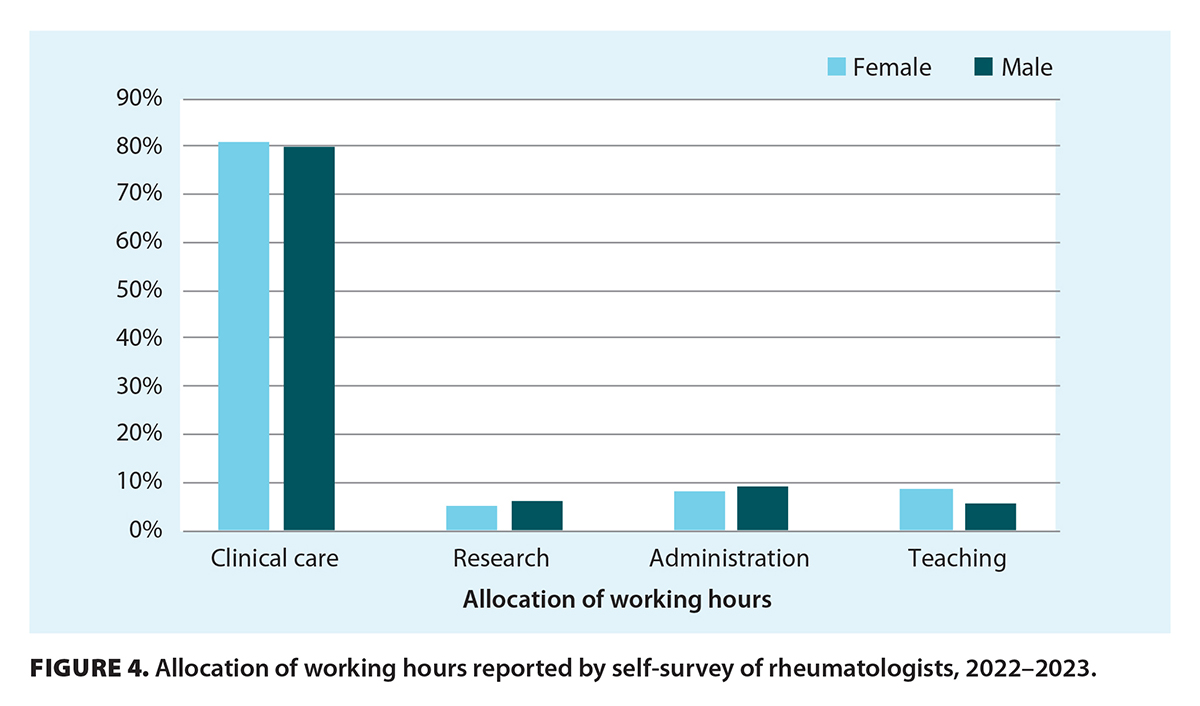

Mean number of hours worked per week by female rheumatologists was similar to that of male rheumatologists: 42.5 hours versus 42.6 hours, respectively (P = .48). Allocation of time for clinical care and other responsibilities (e.g., research, administration, teaching) was relatively equal between women and men [Figure 4]. The overall number of hours female and male rheumatologists spent per week reviewing results and reports (3.5 hours versus 3.9 hours, respectively; P = .28) and reviewing CareConnect for external investigations (2.5 hours for both women and men) was not significantly different. The average time female rheumatologists spent on an initial consultation was 50.4 minutes, whereas male rheumatologists spent on average 40.8 minutes (P = .0032). Increased consult time for female rheumatologists was correlated with a reduction in salary (P = .002), whereas there was no statistically significant correlation between consult time and salary for male rheumatologists (P = .084).

|

|

Female and male rheumatologists reported the following patient presentations in their practice, respectively: mechanical concerns, 16.7% versus 28.0% (P = .08); autoimmune inflammatory arthritis, 52.0% versus 47.7% (not significant); crystal arthritis, 9.9% versus 10.9% (not significant); and complex connective tissue diseases, 25.2% versus 16.3% (P = .038) [Figure 5]. Compared with male rheumatologists, female rheumatologists had a numerically greater proportion of patients with complex additional needs across all domains (hearing loss, dementia, mobility issues, depression, anxiety, history of trauma, refugees, homelessness) except English as a second language, though all results were not statistically significant [Figure 6].

|

|

Discussion

In our study, female and male rheumatologists worked on average the same number of hours per week, but 71.0% of women earned less than $400 000 annually compared with only 33.5% of men.

We compared self-reported annual remuneration to MSP billings. The average self-reported remuneration for 2022–2023 was $384 830 for women and $454 460 for men; MSP billings between 2018 and 2022 showed an average of $348 406 for women and $506 238 for men. These results equate to a pay gap of 15.3% and 31.2%, respectively, in favor of men. This difference is likely because our survey did not capture all rheumatologists practising in BC. Furthermore, because our survey was anonymized, it was not possible to directly compare individual self-reported billings to MSP data.

In addition, the Blue Book billings reported by MSP capture only fee-for-service payments, not other remuneration from, for example, clinical teaching, on-call stipends (Medical On-Call Availability Program), administrative roles, clinical trial funding, and pharmaceutical company honoraria. However, the overall allocation of time among women and men was similar, with about 80% of time spent by both groups on clinical care; thus, most rheumatologist remuneration was from fee-for-service billings.

Compared with male rheumatologists, female rheumatologists more frequently had patients with complex chronic connective tissue disease. Although the results were not statistically significant, male rheumatologists more frequently had patients with mechanical concerns than did female rheumatologists. This was not well captured in our data, but mechanical concerns are frequently accompanied by procedural billing codes (e.g., injections) that increase remuneration, and often less consultation time is required to manage mechanical concerns than complex connective tissue diseases. In addition, female rheumatologists more frequently had patients with complex additional needs across the majority of domains, which may contribute to increased consult length.

In our study, female rheumatologists spent on average 50.4 minutes on an initial consult compared with 40.8 minutes by male rheumatologists. In an average 8-hour working day consisting of only new consults, this equates to 2.3 more new patients seen in a day by male rheumatologists than by female rheumatologists, which is equivalent to a billing difference of $551 daily. In 1 year with an average of 250 working days, this amounts to an annual difference of $137 750. Increased consult time for female rheumatologists was correlated with a reduction in salary. Although more male rheumatologists than female rheumatologists had been in practice for more than 20 years, this was not associated with a difference in billings.

Our study confirms findings from other research studies. In Canada, between 2000 and 2015, male rheumatologists saw 606 more new rheumatology patients per year than did female rheumatologists and had 1059 more follow-up visits.[2] A 2018 survey of Canadian rheumatologists indicated that, overall, there was no statistically significant difference in median hours worked per week by female and male rheumatologists (48 hours and 50 hours, respectively), but women under 50 years of age worked fewer hours than men under 50 years of age (45 hours versus 50 hours, respectively; P = .02).[12]

Based on our study and other published research, it appears that female rheumatologists spend more time with their patients than do male rheumatologists, which results in fewer patients being seen. There may also be a referral bias in favor of women in terms of caring for more psychosocially complex and vulnerable populations. Moreover, patients have different expectations of female and male physicians: patients speak more and disclose more biomedical and psychosocial information with female physicians than with male physicians.[13] Therefore, it seems that both physician and patient factors, along with gendered societal expectations, play a role in lengthier visits with female physicians. Improved outcomes in hospitalized patients[14] and surgical patients[15] have been demonstrated among female physicians and surgeons. These differences in outcomes are multifactorial: female physicians are more likely to adhere to clinical guidelines,[15] provide preventive care more often,[16] use more patient-centred communication,[17] and provide more psychosocial counseling compared with their male colleagues.[18] It remains to be studied whether spending more time with patients leads to improved patient outcomes in rheumatology.

A potential solution to addressing the disparity in consultation times between female and male rheumatologists may be to increase the billing code for complex initial consultations that last more than 53 minutes. This would, in theory, allow for some equalization of earnings. Another possibility is using alternative payment structures, such as a blended model similar to the Longitudinal Family Physician Payment Model that was implemented by the BC Ministry of Health in 2023. It was part of an overhaul of family physicians’ remuneration to acknowledge the increasing complexity of longitudinal care and to provide valuation of time spent with patients.[19] Alternative payments funding may be preferable to fee-for-service in some circumstances because it offers a more predictable rate of income for physicians and provides more reasonable remuneration for certain time-consuming services.

Conclusions

It is important to acknowledge that female and male rheumatologists, and female and male physicians more broadly, may practise medicine differently. However, rather than changing individual practices, we should focus efforts on valuing these different contributions and formulating models that equalize remuneration.

Funding

This was an investigator-led study, and we did not receive any internal or external sources of funding.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to the members of the BCSR for their support of this initiative, survey, and discussion of the results. In particular, we thank Drs Jason Kur and Carson Chin for their leadership as the president and vice-president, respectively, of the BCSR when this study was conducted.

Competing interests

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. Expanding the concept of public health. In: The new public health. 3rd ed. Cambridge, MA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2014. pp. 43-90.

2. Cohen M, Kiran T. Closing the gender pay gap in Canadian medicine. CMAJ 2020;192:E1011-E1017. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200375.

3. Widdifield J, Gatley JM, Pope JE, et al. Feminization of the rheumatology workforce: A longitudinal evaluation of patient volumes, practice sizes, and physician remuneration. J Rheumatol 2021;48:1090-1097. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.201166.

4. Ministry of Health. MSC financial statement (blue book). Accessed 14 November 2024. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/msp/publications.

5. Frank E, Zhao Z, Sen S, Guille C. Gender disparities in work and parental status among early career physicians. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e198340. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8340.

6. Jolly S, Griffith KA, DeCastro R, et al. Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician-researchers. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:344-353. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-0974.

7. Crossley TF, Hurley J, Jeon S-H. Physician labour supply in Canada: A cohort analysis. Health Econ 2009;18:437-456. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1378.

8. Phillips CB. Student portfolios and the hidden curriculum on gender: Mapping exclusion. Med Educ 2009;43:847-853. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03403.x.

9. Kwon E, Adams TL. Choosing a specialty: Intersections of gender and race among Asian and White women medical students in Ontario. Can Ethn Stud 2018;50:49-68. https://doi.org/10.1353/CES.2018.0022.

10. Mascarenhas A, Moore JE, Tricco AC, et al. Perceptions and experiences of a gender gap at a Canadian research institute and potential strategies to mitigate this gap: A sequential mixed-methods study. CMAJ Open 2017;5:E144-E151. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20160114.

11. Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, et al. Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA 2015;314:1149-1158. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.10680.

12. Barber CEH, Nasr M, Barnabe C, et al. Planning for the rheumatologist workforce: Factors associated with work hours and volumes. J Clin Rheumatol 2019;25:142-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/RHU.0000000000000803.

13. Hall JA, Roter DL. Do patients talk differently to male and female physicians? A meta-analytic review. Patient Educ Couns 2002;48:217-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00174-x.

14. Tsugawa Y, Jena AB, Figueroa JF, et al. Comparison of hospital mortality and readmission rates for Medicare patients treated by male vs female physicians. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:206-213. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7875.

15. Wallis CJD, Jerath A, Ikesu R, et al. Association between patient-surgeon gender concordance and mortality after surgery in the United States: Retrospective observational study. BMJ 2023;383:e075484. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2023-075484.

16. Frank E, Dresner Y, Shani M, Vinker S. The association between physicians’ and patients’ preventive health practices. CMAJ 2013;185:649-654. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.121028.

17. Krupat E, Rosenkranz SL, Yeager CM, et al. The practice orientations of physicians and patients: The effect of doctor–patient congruence on satisfaction. Patient Educ Couns 2000;39:49-59. http://doi.org/10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00090-7.

18. Roter DL, Hall JA, Aoki Y. Physician gender effects in medical communication: A meta-analytic review. JAMA 2002;288:756-764. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.6.756.

19. Ministry of Health. Medical Services Commission Payment Schedule. 2021. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/medical-services-plan/msc-payment-schedule-may-2021.pdf.

Dr Hu is a clinical instructor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia. Dr Blumenauer is a rheumatologist in Kamloops. Dr Kazem is a clinical instructor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Baldwin is a clinical assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Kherani is a clinical associate professor and residency program director in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Jamal is a clinical professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Day is a rheumatologist in West Vancouver. Dr Stewart is a clinical assistant professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Wright is president of the Association of Women in Rheumatology. Dr Melton is vice-president of the Association of Women in Rheumatology. Dr Shojania is head of rheumatology at Vancouver General Hospital and a clinical professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Lacaille is scientific director of Arthritis Research Canada and a professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Carruthers is a clinical associate professor in the Division of Rheumatology, Faculty of Medicine, UBC.

Corresponding author: Dr Angela Hu, angela.hu@medportal.ca.