Review Articles

Diagnosis and management of irritable bowel syndrome in the primary care setting

ABSTRACT: Irritable bowel syndrome is a common, chronic disorder of gut–brain interaction with complex pathophysiology. It is characterized by abdominal pain and alterations in bowel movements, currently diagnosed based on the Rome IV criteria. If alarm symptoms are present, objective workup may be required to exclude organic etiologies. Irritable bowel syndrome remains a frequent reason to visit primary care physicians and gastroenterologists. It puts a significant burden on patients’ quality of life and has high economic costs. Given limited access to gastroenterology consultation, initiating treatment promptly in the primary care setting should be the standard of care to minimize patients’ pain and suffering. Treatment requires a patient-centred approach and often multiple treatment options, including dietary management, pharmacotherapy, and psychological approaches, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and gut-directed hypnotherapy.

Diagnosing and promptly initiating treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in the primary care setting should be the standard of care to minimize patients’ pain and suffering.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic disorder of gut–brain interaction, characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits.[1] Approximately 4.1% of adults globally are affected by the disorder, based on the Rome IV criteria.[2] IBS has negative impacts on patients’ health-related quality of life[3] and results in a significant direct and indirect socioeconomic and health care burden.[4,5]

Clinical cases

Case 1

![FIGURE 1. Classification of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) based on percentage of bowel movements in Bristol stool chart6 categories. Adapted from Lacy and colleagues.[1]](https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol66_No8_IBS_web_Figure1.jpg) Patient 1 is a 35-year-old woman who has had ongoing abdominal pain and diarrhea for several years. Her medical history includes hypothyroidism, which was treated with levothyroxine, and generalized anxiety disorder. She has been experiencing daily lower abdominal pain for the past 5 years. She has one bowel movement shortly after waking, followed by two or three bowel movements (Bristol stool type 6 [Figure 1][6]) associated with increasing abdominal cramps after passing stools, which last 1–2 hours. There is no sign of gastrointestinal bleeding or constitutional symptoms. Physical examination is unremarkable. Does she have IBS?

Patient 1 is a 35-year-old woman who has had ongoing abdominal pain and diarrhea for several years. Her medical history includes hypothyroidism, which was treated with levothyroxine, and generalized anxiety disorder. She has been experiencing daily lower abdominal pain for the past 5 years. She has one bowel movement shortly after waking, followed by two or three bowel movements (Bristol stool type 6 [Figure 1][6]) associated with increasing abdominal cramps after passing stools, which last 1–2 hours. There is no sign of gastrointestinal bleeding or constitutional symptoms. Physical examination is unremarkable. Does she have IBS?

Case 2

Patient 2 is a 42-year-old man with chronic constipation and abdominal discomfort, which has gradually worsened over the past 3 years. He has gastroesophageal reflux disease, which is managed with occasional antacids. Over the past year, he has had infrequent Bristol stool type 1 bowel movements [Figure 1], typically once per week, despite having a high-fibre diet and adequate hydration. He has a sensation of incomplete evacuation despite prolonged straining, with difficult-to-pass stool, bloating, and lower abdominal pain. He does not have rectal bleeding, unintentional weight loss, or family history of gastrointestinal disorders. On physical examination, he has a soft abdomen with mild tenderness in the left lower quadrant. Does he have IBS?

Pathophysiology

IBS is a multifactorial chronic disorder with complex pathophysiology. It tends to be more common in adults between 20 and 40 years of age.[7] Imbalances in the gut–brain communication can lead to motility disturbances, visceral hypersensitivity, and altered central nervous system processing,[8] resulting in amplified pain or discomfort in response to innoxious stimuli.[9] Psychological factors may further negatively impact gut function through intricate communication pathways.[9] Low-grade inflammation at the microscopic level along the intestines has been implicated in IBS pathogenesis and is potentially triggered by immune activation and changes in mucosal barrier function, particularly following an acute enteric infection, a well-known entity of postinfectious IBS.[10] COVID-19 infection can also increase the risk of developing IBS.[11] Furthermore, imbalances in gut microbiota have been observed in IBS patients, which affect gastrointestinal symptoms through alterations in fermentation patterns and immune responses. Brachyspira colonization may play a role in the development of IBS with diarrhea (IBS-D); there is increased detection in affected patients, although the mechanism of colonization is not known, and testing and treatment remain unavailable outside of clinical trials.[12] Genetic predisposition and environmental factors, such as diet, infections, and early life events, also contribute to IBS susceptibility, which underscores the complex interplay of genetic and environmental influences in its development.[10]

Clinical features and diagnosis

![FIGURE 2. Diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome, based on Rome IV criteria.[1,13]](https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol66_No8_IBS_web_Figure2_0.jpg) IBS presents with abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits, outlined in Rome IV criteria [Box]. It is further classified based on predominant stool pattern [Figure 1]. Diagnosis of IBS requires a detailed history, with attention to the pattern of abdominal pain and its association with bowel habits, review of alarm symptoms and signs, limited diagnostic tests, and careful follow-up. Positive diagnosis can be made in primary care settings based on Rome IV criteria [Figure 2], which avoids unnecessary tests and delays in providing appropriate patient care.

IBS presents with abdominal pain and changes in bowel habits, outlined in Rome IV criteria [Box]. It is further classified based on predominant stool pattern [Figure 1]. Diagnosis of IBS requires a detailed history, with attention to the pattern of abdominal pain and its association with bowel habits, review of alarm symptoms and signs, limited diagnostic tests, and careful follow-up. Positive diagnosis can be made in primary care settings based on Rome IV criteria [Figure 2], which avoids unnecessary tests and delays in providing appropriate patient care.

If clinically indicated, limited diagnostic tests may be required, such as complete blood count and iron studies. Celiac serological testing is recommended in IBS workup.[13] In IBS-D, stool infectious workup, including Clostridioides difficile toxin, may be required. C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, food allergy testing, and lactose/glucose/lactulose hydrogen breath tests are not recommended in initial evaluation of IBS.[13]

Colonoscopy is not routinely required to make a positive diagnosis of IBS [Figure 2]. If alarm symptoms are present or there is a new onset of IBS symptoms in a patient 50 years of age or older, colonoscopy is recommended to rule out organic etiologies.[13]

Treatment

Treatment of IBS requires a patient-centred approach. Given the multifaceted nature of the disorder, often multiple treatment options are required to improve global symptoms of the disorder.

Dietary management

Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) may worsen IBS symptoms by increasing colonic gas production through fermentation and increasing small intestinal water content, leading to diarrhea.[14] A low-FODMAP diet can improve abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea.[15] However, implementing the diet can be challenging and is most successful under the direction of a dietitian. A low-FODMAP diet should be continued for 4 to 6 weeks, after which FODMAPs can be carefully reintroduced.[16] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) diet is a less restrictive alternative that involves regulating meal times and portions; maintaining adequate fluid intake; and avoiding dietary triggers such as tea, coffee, alcohol, carbonated drinks, insoluble fibre, resistant starch, and sorbitol.[17] Patients should be counseled to avoid a prolonged restrictive phase because it may lead to development of nutritional deficiency and aversive behaviors toward food.

In patients with constipation-predominant symptoms, the addition of two green kiwi-fruit daily improves bowel movement frequency, form, straining, and bloating without adverse effects and results in greater patient satisfaction when compared with prunes and psyllium.[18]

Psychological approaches

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is a nonpharmacologic approach that has been shown to be beneficial in the management of IBS symptoms, quality of life, and psychological states,[19] with sustained improvement at 24 months.[20] Cognitive-behavioral therapy can be delivered virtually through platforms such as Mahana IBS to reduce global symptoms, particularly when in-person access to cognitive-behavioral therapy providers is limited.[21] Gut-directed hypnotherapy is another approach to improve global IBS symptoms.[13,22]

Pharmacotherapy

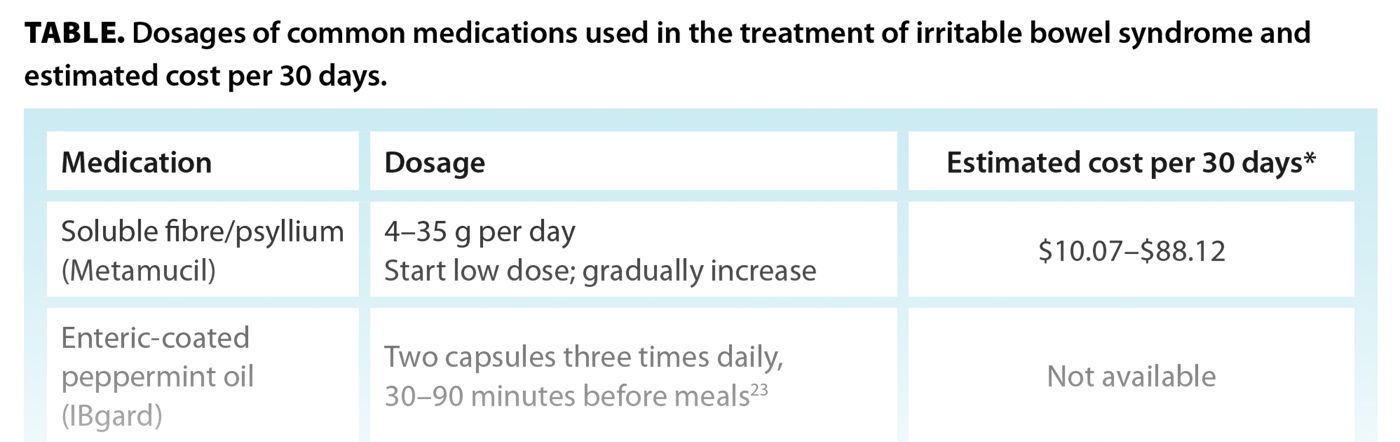

The following outlines the clinical use of, and evidence for, various pharmacologic treatment options for IBS. Dosages and estimated costs of these treatments are provided in the Table.

Enteric-coated peppermint oil

Peppermint oil (e.g., small intestinal release formulation IBgard[23]) has been shown to improve abdominal bloating, pain, and global symptoms of IBS through calcium channel blockade and relaxation of intestinal smooth muscle cells, modulation of visceral pain sensation, anti-inflammatory effects, and alterations in the gut microbiome.[24] Minimal side effects include gastroesophageal reflux, dyspepsia, and flatulence.[25]

Soluble fibre

Soluble fibre aids in water absorption, adds to stool bulk and softens it, stimulates secondary peristalsis, and promotes regular bowel movements. It is superior to placebo in improving global symptoms of IBS. Conversely, insoluble fibre, such as bran, may cause worsening bloating and gas and is therefore not recommended for IBS management.[26]

Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics

Probiotics are orally administered bacteria, often used in the management of various gastrointestinal disorders. Probiotics may improve global symptoms, abdominal pain, and bloating in patients with IBS-D, but not those with IBS with constipation (IBS-C).[27] Due to the lack of adequate response in meta-analyses for IBS or constipation, no definitive recommendation can be provided for the clinical use of probiotics. Patients with IBS may consider a short course of probiotics.[13] If there is no clinical response, probiotics should be stopped. Prebiotics are nutritional products that stimulate bacterial growth; limited studies support their use in IBS. Synbiotics are a combination of prebiotics and probiotics, which can improve global IBS symptoms.[28]

IBS-D pharmacotherapy

Loperamide

Loperamide is a peripherally acting opioid agonist that inhibits gastrointestinal motility and reduces diarrhea. It improves stool frequency and consistency in IBS-D; however, it does not improve global IBS symptoms.[29] Treatment with loperamide is safe; side effects include constipation, nausea, and abdominal pain.[30] Cases of cardiac arrhythmias have been reported with excess dosing.[31] Contraindications include acute dysentery, ulcerative colitis, invasive bacterial enterocolitis, and pseudomembranous colitis.[30]

Bile acid sequestrants

Bile acid malabsorption can cause chronic diarrhea; it occurs in 28.1% of IBS-D patients.[32] Risk factors for bile acid malabsorption include elevated body mass index, ileocecal valve/terminal ileal resection, and previous cholecystectomy.[33,34] Given the limited availability of SeHCAT testing in Canada, empiric use of bile acid sequestrants in patients with functional diarrhea can reduce stool frequency.[33] Colestipol, cholestyramine,[35] and colesevelam are available for use.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants can improve global IBS symptoms. Amitriptyline at a starting dose of 10 mg, uptitrated to 30 mg, daily can improve IBS symptoms.[36] The most common side effects of tricyclic antidepressants include dry mouth, constipation, and drowsiness.[22]

Patient education remains pivotal in explaining the rationale for the use of tricyclic antidepressants in the management of IBS symptoms to avoid negative stigma, often perceived with the use of antidepressants to manage disorders of the gut–brain interaction.

Rifaximin

Rifaximin, a minimally absorbed antibiotic, can offer benefit in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and IBS-D by modulating dysbiosis in gut microbiota.[37] Risk factors for small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in IBS include female sex, older age, and IBS-D subtype.[38] Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth breath testing is often not readily available and has limitations; empiric therapy with rifaximin is considered reasonable, though it may be cost-prohibitive. Rifaximin improves global IBS symptoms and bloating and does not increase adverse effects.[39,40] In patients who initially respond to rifaximin and have a relapse of symptoms, or in those with no initial response, repeated 2-week courses of treatment up to three times can improve global symptoms and abdominal pain without additional adverse effects.[41]

Eluxadoline

Eluxadoline, a mixed mu-opioid receptor agonist and delta-opioid receptor antagonist, was approved for IBS-D. It significantly improves abdominal pain and stool consistency.[42] Adverse effects include nausea; constipation; abdominal pain; and, rarely, pancreatitis in patients with underlying risk factors.[42] Contraindications include pancreaticobiliary disease, previous cholecystectomy, alcohol use of more than two drinks per day, hepatic impairment, and treatment with OATP1B1 inhibitors (e.g., cyclosporin).[43]

IBS-C pharmacotherapy

Osmotic laxatives

Osmotic laxatives draw water into the intestines, thereby augmenting stool volume and softening its consistency to facilitate bowel movements. While robust evidence supports their utility in chronic idiopathic constipation, their benefit in global IBS-C symptoms is limited.[44,45] However, they could be used as adjunctive therapy to improve constipation.[13] Polyethylene glycol (PEG) or magnesium formulations are commonly used osmotic laxatives.

Guanylate cyclase-C agonists

Guanylate cyclase-C agonists, including linaclotide and plecanatide, stimulate the secretion of chloride and bicarbonate ions into the intestines and increase fluid secretion and hence stool bulk, which promotes secondary peristalsis and increases bowel movements. Linaclotide reduces abdominal pain and increases complete spontaneous bowel movement.[46,47] While an improvement in stool frequency occurs within 1 week of treatment initiation, maximal improvement, particularly in abdominal pain, may take up to 8 to 12 weeks.[48] Plecanatide also significantly improves abdominal pain and constipation in as little as 1 to 2 weeks after the initial dose. It has minimal side effects and a well-tolerated safety profile.[49] The most common adverse effect of these agonists is diarrhea, reported in up to 20% of patients taking the higher dose of linaclotide and 4% of those taking plecanatide.[49,50] This can be mitigated by administering the agent 30 to 60 minutes before breakfast and counseling the patient regarding side effects, which anecdotally settle after a few weeks.

Sodium–hydrogen exchange inhibitor

Tenapanor, a sodium–hydrogen exchange inhibitor, works by inhibiting the sodium–hydrogen exchanger protein in the intestines, thereby reducing sodium absorption. Consequently, the increased luminal osmotic load reduces fluid absorption and enhances intestinal transit. Tenapanor significantly improves abdominal pain and increases complete spontaneous bowel movements.[51] Side effects may include diarrhea, flatulence, borborygmi, and abdominal cramps.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in IBS may alleviate global symptoms by increasing serotonin levels to promote centrally mediated effects on gut mobility and visceral sensation. Compared with placebo, SSRIs improve global IBS symptoms; however, uncertainty remains due to inconsistency, heterogeneity of date, and imprecision in the evidence.[22] The American Gastroenterological Association recommends against the use of SSRIs in IBS-C management; however, the Canadian Association of Gastroenterology suggests offering SSRIs to IBS patients to improve symptoms.[13,52]

Clinical cases follow-up

Patient 1 showed no family history of colon cancer. Her initial investigation with celiac serology and stool infectious workup were negative. She received a diagnosis of IBS-D and was referred to a dietitian to implement a low-FODMAP diet and used over-the-counter loperamide to improve her stool form. After 1 month of treatment, she still suffered from daily abdominal pain. Her loperamide was discontinued, and she was started on amitriptyline, 10 mg per day for 3 weeks, then increased to 20 mg per day, which improved her global IBS symptoms.

Patient 2 had unremarkable workup, and his complete blood count, ferritin, and negative celiac serology showed no abnormalities. He had ongoing abdominal pain and constipation so was given a diagnosis of IBS-C. He incorporated soluble fibre, ate two or three green kiwifruits daily, and took PEG laxatives daily. While he had some relief, his constipation and abdominal discomfort persisted. He was started on plecanatide 3 mg daily and showed significant improvement in his global IBS symptoms within 2 weeks.

Conclusions

IBS is a complex, multifactorial, chronic condition that has a significant impact on the patient’s quality of life, causes loss of productivity, and results in considerable health care costs. In the absence of alarm symptoms, positive diagnosis of IBS should be made in the primary care setting, with no delay in implementing the aforementioned evidence-based interventions. Patients with severe symptoms and those with inadequate response to initial therapies may be referred to gastroenterology for further evaluation and management.

Competing interests

None declared.

BOX. Rome IV criteria for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. Adapted from Lacy and colleagues.[1]

Recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day per week in the last 3 months, associated with two or all of the following criteria:

- Related to defecation.

- Associated with a change in stool frequency.

- Associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L, et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1393-1407.e5.

2. Sperber AD, Bangdiwala SI, Drossman DA, et al. Worldwide prevalence and burden of functional gastrointestinal disorders, results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology 2021;160:99-114.e3.

3. Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al. The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000;119:654-660.

4. Longstreth GF, Wilson A, Knight K, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome, health care use, and costs: A U.S. managed care perspective. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:600-607.

5. Goodoory VC, Ng CE, Black CJ, Ford AC. Impact of Rome IV irritable bowel syndrome on work and activities of daily living. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;56:844-856.

6. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997;32:920-924.

7. Oka P, Parr H, Barberio B, et al. Global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome according to Rome III or IV criteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5:908-917.

8. Ford AC, Sperber AD, Corsetti M, Camilleri M. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 2020;396(10263):1675-1688.

9. Saha L. Irritable bowel syndrome: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and evidence-based medicine. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:6759-6773.

10. Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;1:133-146.

11. Marasco G, Cremon C, Barbaro MR, et al. Post COVID-19 irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2023;72:484-492.

12. Jabbar KS, Dolan B, Eklund L, et al. Association between Brachyspira and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Gut 2021;70:1117-1129.

13. Moayyedi P, Andrews CN, MacQueen G, et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology clinical practice guideline for the management of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2019;2:6-29.

14. Staudacher HM, Whelan K. The low FODMAP diet: Recent advances in understanding its mechanisms and efficacy in IBS. Gut 2017;66:1517-1527.

15. Black CJ, Staudacher HM, Ford AC. Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2022;71:1117-1126.

16. Barrett JS. How to institute the low-FODMAP diet. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;32(Suppl 1):8-10.

17. Werlang ME, Palmer WC, Lacy BE. Irritable bowel syndrome and dietary interventions. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;15:16-26.

18. Chey SW, Chey WD, Jackson K, Eswaran S. Exploratory comparative effectiveness trial of green kiwifruit, psyllium, or prunes in US patients with chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:1304-1312.

19. Li L, Xiong L, Zhang S, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res 2014;77:1-12.

20. Everitt HA, Landau S, O’Reilly G, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: 24-month follow-up of participants in the ACTIB randomised trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;4:863-872.

21. Everitt HA, Landau S, O’Reilly G, et al. Assessing telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and web-delivered CBT versus treatment as usual in irritable bowel syndrome (ACTIB): A multicentre randomised trial. Gut 2019;68:1613-1623.

22. Ford AC, Lacy BE, Harris LA, et al. Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:21-39.

23. Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig Dis Sci 2016;61:560-571.

24. Chumpitazi BP, Kearns GL, Shulman RJ. Review article: The physiological effects and safety of peppermint oil and its efficacy in irritable bowel syndrome and other functional disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:738-752.

25. Ingrosso MR, Ianiro G, Nee J, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Efficacy of peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022;56:932-941.

26. Moayyedi P, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, et al. The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1367-1374.

27. Goodoory VC, Khasawneh M, Black CJ, et al. Efficacy of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2023;165:1206-1218.

28. Ford AC, Quigley EMM, Lacy BE, et al. Efficacy of prebiotics, probiotics, and synbiotics in irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:1547-1561.

29. Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacologic treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:136-147.

30. Janssen Pharmaceutica Inc. Imodium® (loperamide hydrochloride). 1998. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2005/017694s050lbl.pdf.

31. Swank KA, Wu E, Kortepeter C, et al. Adverse event detection using the FDA post-marketing drug safety surveillance system: Cardiotoxicity associated with loperamide abuse and misuse. J Am Pharm Assoc 2017;57:S63-S67.

32. Slattery SA, Niaz O, Aziz Q, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:3-11.

33. Williams AJ, Merrick MV, Eastwood MA. Idiopathic bile acid malabsorption—A review of clinical presentation, diagnosis, and response to treatment. Gut 1991;32:1004-1006.

34. Gracie DJ, Kane JS, Mumtaz S, et al. Prevalence of, and predictors of, bile acid malabsorption in outpatients with chronic diarrhea. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2012;24:983- e538.

35. Odan Laboratories Ltd. Cholestyramine-Odan [product monograph]. 2016. Accessed 9 July 2024. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00035221.PDF.

36. Ford AC, Wright-Hughes A, Alderson SL, et al. Amitriptyline at low-dose and titrated for irritable bowel syndrome as second-line treatment in primary care (ATLANTIS): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2023;402(10414):1773-1785.

37. Pimentel M. Review article: Potential mechanisms of action of rifaximin in the management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43(Suppl 1):37-49.

38. Chen B, Kim JJ-W, Zhang Y, et al. Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol 2018;53:807-818.

39. Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Engl J Med 2011;364:22-32.

40. Menees SB, Maneerattannaporn M, Kim HM, Chey WD. The efficacy and safety of rifaximin for the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:28-35.

41. Lembo A, Pimentel M, Rao SS, et al. Repeat treatment with rifaximin is safe and effective in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2016;151:1113-1121.

42. Lembo AJ, Lacy BE, Zuckerman MJ, et al. Eluxadoline for irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2016;374:242-253.

43. Allergan Pharma Co. Eluxadoline (Viberzi®). Product monograph including patient medication information. 2015.

44. Khoshoo V, Armstead C, Landry L. Effect of a laxative with and without tegaserod in adolescents with constipation predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:191-196.

45. Chapman RW, Stanghellini V, Geraint M, Halphen M. Randomized clinical trial: Macrogol/PEG 3350 plus electrolytes for treatment of patients with constipation associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1508-1515.

46. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Lavins BJ, et al. Linaclotide for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: A 26-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate efficacy and safety. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1702-1712.

47. Rao S, Lembo AJ, Shiff SJ, et al. A 12-week, randomized, controlled trial with a 4-week randomized withdrawal period to evaluate the efficacy and safety of linaclotide in irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1714-1724.

48. Chey WD, Kurlander J, Eswaran S. Irritable bowel syndrome: A clinical review. JAMA 2015;313:949-958.

49. Brenner DM, Fogel R, Dorn SD, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of plecanatide in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: Results of two phase 3 randomized clinical trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:735-745.

50. Miner PB Jr, Koltun WD, Wiener GJ, et al. A randomized phase III clinical trial of plecanatide, a uroguanylin analog, in patients with chronic idiopathic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:613-621.

51. Chey WD, Lembo AJ, Yang Y, Rosenbaum DP. Efficacy of tenapanor in treating patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: A 26-week, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial (T3MPO-2). Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:1294-1303.

52. Chang L, Sultan S, Lembo A, et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on the pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology 2022;163:118-136.

Drs Hemy and Zhu are internal medicine residents in the Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia. Dr Moosavi is a gastroenterologist and clinical assistant professor in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, UBC.

Corresponding author: Dr Sarvee Moosavi, sarvee.moosavi@gmail.com.