Community-based consultant pediatrician perspectives on child and youth mental health in British Columbia

ABSTRACT

Background: Child and youth mental health concerns are increasing in Canada, resulting in an increase in visits to community providers.

Methods: We distributed a 14-question survey to members of the British Columbia Pediatric Society (N = 309) in February 2025 to explore the role community-based consultant pediatricians (CBCPs) play in delivering pediatric mental health services in British Columbia.

Results: The response rate was 26% (n = 81). Mental health care now comprises most of the care that CBCPs provide, and this has increased significantly over the last decade. Due in part to self-directed learning, CBCPs appear comfortable caring for straightforward concerns. Yet, as they shoulder the burden of complex mental health care with insufficient support, they are grappling with burnout and professional sustainability.

Conclusions: The current delivery of BC’s pediatric mental health care system has placed CBCPs in an untenable situation. Because this issue threatens the long-term viability of the community pediatric workforce, we need to consider strategies that more effectively meet changing pediatric mental health care needs.

The increasing demand on community-based consultant pediatricians in BC to provide pediatric mental health services appears unsustainable and presents a threat to the long-term viability of their workforce.

Background

Optimal mental health is paramount for children and youth to grow and develop to the best of their abilities. However, significant mental health conditions, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety disorders, mood disorders, autism, and behavior disorders, globally affect nearly 7% of children 5 to 9 years of age and approximately 13% of those 10 to 19 years of age.[1] In Canada, recent estimates indicate that mental illness affects 1.2 million children and youth.[2] The COVID-19 pandemic had significant impacts, with nearly one in five youth who rated their mental health as “good” or better in 2019 reporting declines to “fair” or “poor” by 2023.[3] During the pandemic’s peak and aftermath, there were significant increases in hospital admissions for pediatric mental health concerns and deteriorations in mental well-being.[4] Yet even in the decade prior to the pandemic, these concerns in Canadian children and youth were increasing. Thirty-nine percent of Ontario students in grades 7 to 12 reported a moderate to severe level of psychological distress,[5] while anxiety disorders doubled in the pediatric population.[6]

There is international consensus that countries should provide comprehensive pediatric mental health services because they are “essential to realize [children and youth’s] full rights, [to] ensure that they can meet their potential, [to] alleviate unnecessary suffering, and to enable sustainable development and foster prosperous, stable communities.”[7] Community physicians, including pediatricians, are one component of this system of care; over the last 6 years in Canada, they have seen a nearly 10% increase in child and youth visits for mental health concerns.[8] In this context, and with the improvement of child and youth mental health care as one of the Canadian Paediatric Society’s current strategic priorities,[9] we sought to better understand the current role that community-based consultant pediatricians (CBCPs) play in the delivery of these services in British Columbia.

Methods

Study design

Following iterative discussions with British Columbia Pediatric Society Advocacy Committee members, we developed a 14-question survey to explore the perspectives of CBCPs regarding their experiences with providing mental health care. The survey included closed- and open-ended questions to assess the volume and complexity of mental health care CBCPs provide, their comfort and training in providing such care, perceived supports, and impacts on their well-being and career plans. We distributed the survey, in English, by email in February 2025 to 458 recipients, including all members of the British Columbia Pediatric Society and the American Academy of Pediatrics–BC Chapter. We obtained responses confidentially through a secure online platform (SurveyMonkey).

Data collection and analysis

The British Columbia Pediatric Society compiled the initial results of this study. We included only actively practising members of the British Columbia Pediatric Society or the American Academy of Pediatrics–BC Chapter (N = 309; British Columbia Pediatric Society: 222 active members, 17 associate members, 35 first-year-in-practice members; American Academy of Pediatrics–BC Chapter: 35 members). We excluded residents (n = 119), medical students (n = 19), and retired or administrative members (n = 17). We collated responses to closed-ended questions to develop a picture of the contexts in which CBCPs currently practise, determine the current percentage of their clinical work they devote to mental health care, and establish trends in these efforts over time. We analyzed free-response questions thematically.[10] B.S. developed initial codes from the data, which were then reviewed by S.T. and B.E.; B.S. then constructed provisional broader themes, for which the research team achieved consensus through discussion.

Ethics

Because this study was conducted under the aegis of programmatic improvement, it was exempt from ethics review, in keeping with the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans, Article 2.5.

Results

Eighty-nine participants responded to the survey. Eight were removed because they either were still in residency (n = 1) or were not providing any aspect of community-based general pediatric care (n = 7). As a result, our adjusted response rate was 26% (81/309). Closed-ended results are presented as absolute numbers or percentages; free-response results are presented as themes supported by percentages and exemplar quotations [Box]. Denominators vary slightly for free-response results because not every participant responded to every question.

Practice context

Fifty-four percent of respondents (44/81) worked in more than one clinical setting. Seventy-nine percent (64/81) worked in an outpatient community-based practice; 28% (23/81) worked solely in that context. Fifty-three percent of respondents (43/81) worked in a community hospital with specific pediatric inpatient services; 11% (9/81) worked in a community hospital that lacked pediatric-specific services. Sixteen percent of respondents (13/81) who worked in an outpatient community-based practice also worked in the province’s sole pediatric tertiary-quaternary centre. Seventy-five percent of respondents (61/81) worked in a large population centre (more than 100 000 people), 22% (18/81) worked in a medium-sized population centre (30 000 to 100 000 people), and 16% (13/81) worked in a small population centre (1000 to 29 999 people). Fourteen percent of respondents (11/81) worked in more than one population centre.

Mental health care provision over time

Ninety-four percent of respondents (76/81) spent at least 50% of their time working with children with mental health concerns; 53% (43/81) spent 75% or more of their time [Figure 1].

Ninety-four percent of respondents (76/81) spent at least 50% of their time working with children with mental health concerns; 53% (43/81) spent 75% or more of their time [Figure 1].

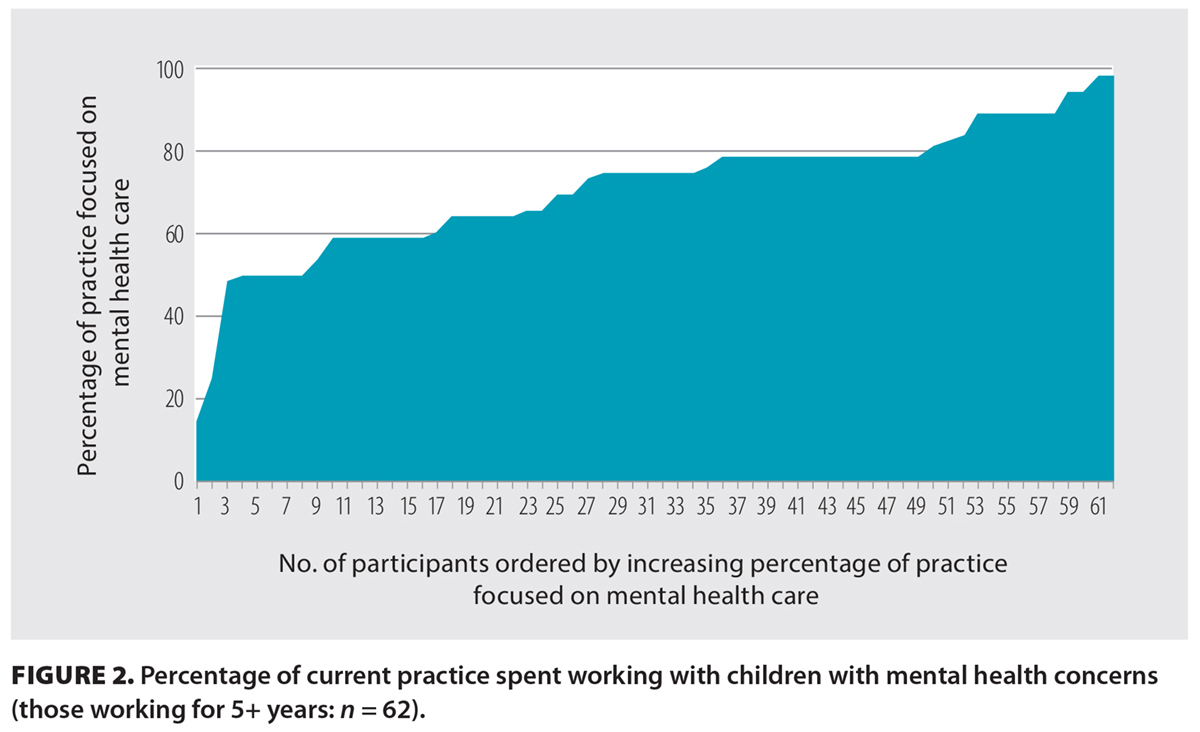

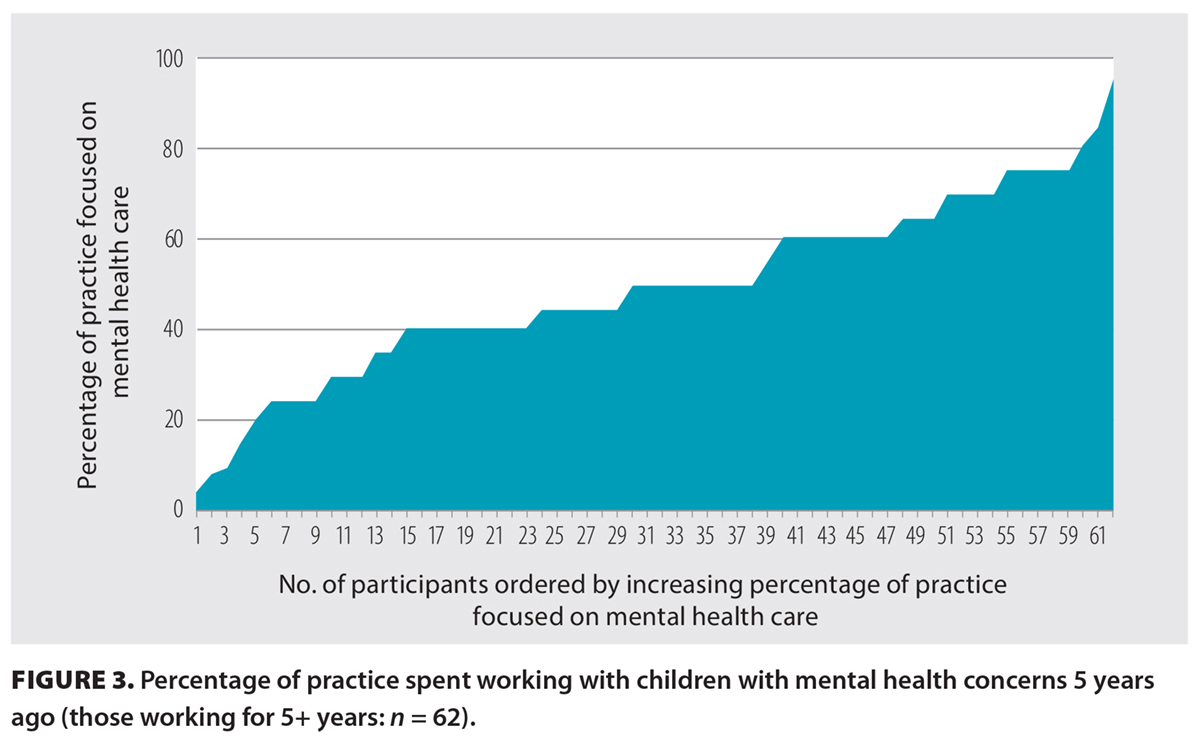

To establish trends over time, we compared how perceptions of the amount of time spent providing services to children with mental health concerns changed among respondents who had worked for 5 years or longer (n = 62) and those who had worked for 10 years or longer (n = 46). Of those who had worked for 5 years or longer, 95% (59/62) spent at least 50% of their time working with these children; 56% (35/62) dedicated at least 75% of their time to that work [Figure 2]. Fifty-three percent (33/62) recalled spending more than half their time working with this population 5 years prior, while only 13% (8/62) recalled spending 75% or more of their time [Figure 3].

|

|

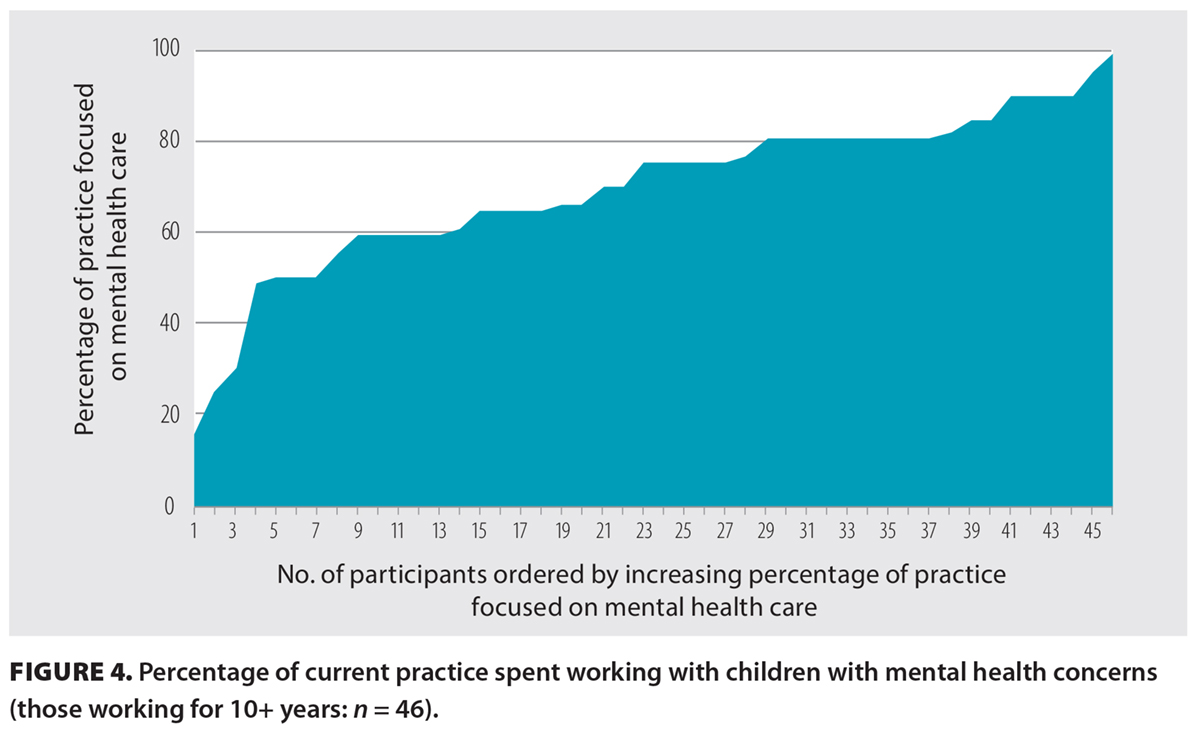

For respondents who had worked for 10 years or longer, 91% (42/46) spent at least 50% of their time working with children with mental health concerns; 54% (25/46) spent at least 75% of their time working with them [Figure 4]. Fifty percent (23/46) recalled spending at least half their time working with these children 5 years prior, while 11% (5/46) recalled spending 75% or more of their time. Twenty-eight percent (13/46) recalled spending half their time or more with this population 10 years prior, while only one respondent recalled spending more than 75% of their time [Figure 5].

|

|

Free responses

Free-response questions focused on CBCP perspectives on their comfort with providing mental health care and their ability to do so, relevant residency training, additional learning/training undertaken, how well they felt their care delivery was supported by other services, and the impacts of this care on their personal and professional lives.

Comfort level and overall individual ability: Eighty percent (63/79) of participants felt comfortable caring for children and youth with straightforward mental health concerns. However, they felt ill at ease with complex presentations and felt that this level of care was beyond their scope.

Postgraduate training and continuing professional development: Respondents’ comfort level with treating straightforward mental health concerns did not appear to result from preparation through residency. Ninety-four percent (76/81) reported they had no or only minimal postgraduate training for this kind of care; 89% (72/81) felt that they were, at best, minimally prepared to provide effective care for these concerns when they started independent practice. Relevant training that was reported included psychiatry rotations/electives (n = 21), community pediatric rotations (n = 11), developmental pediatric rotations/electives (n = 9), and adolescent medicine electives (n = 5).

To fill this gap in training, 84% (64/76) of respondents had engaged in professional development activities. Of these 64 respondents, 89% sought out structured continuing medical education (e.g., conferences offered by the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance, Canadian Paediatric Society, and British Columbia Pediatric Society), 47% had engaged in self-study and/or participated in journal clubs or webinars, 41% had taken a formal course such as CanREACH (a focused training program on child and youth mental health targeted at primary care providers)[11] or learned cognitive-behavioral therapy, and 22% described experiential learning through providing mental health care and/or discussing care strategies with pediatric colleagues.

Supports from other services: While respondents had developed comfort with treating certain concerns, they recognized that effective mental health care provision requires myriad other supports. Seventy-nine participants described how they felt with respect to other mental health or psychiatric services. Of those who described their perceptions overall, 87% (33/38) felt poorly supported, and 84% (38/45) felt that no or only marginal community-based supports were readily available, such as assessment and treatment options that the provincial Child and Youth Mental Health service ostensibly provides.

Sixty-three percent of respondents (31/49) described poor access to child/adolescent psychiatry, an issue that is compounded by the fact that children with significant mental health complexity are often assessed only once, and no longitudinal follow-up is provided. Some respondents found the provincial Compass program—in which CBCPs remotely review a case with a psychiatrist and receive advice—to be more useful. Fifty-five percent (30/55) said Compass had moderate utility, but 33% (18/55) found that it was not helpful. However, even those who felt that Compass had some use raised concerns about the variability of support and the cumbersome process of getting advice; they also felt that it was not a legitimate substitute for psychiatric evaluation.

Personal and professional impacts: Respondents described significant negative impacts on their overall well-being. Eighty-six percent (68/79) said that the current scope of mental health care they provide is exhausting and causes anxiety, burnout, and moral distress. Due to these care experiences and current demands, 42% (33/79) are considering reducing or no longer offering mental health care, leaving community pediatrics, or even leaving the profession. Another 14% (11/79) have already closed their wait list, altered their practice, or made definitive plans to leave the profession entirely.

Discussion

Our results suggest that mental health concerns have increased significantly over the last decade and now comprise most of the care that CBCPs in BC provide. While the CBCPs in this study had no or only minimal relevant mental health care training prior to independent practice, they nonetheless appeared to be comfortable caring for children and youth with straightforward mental health concerns. This level of comfort is a result, at least in part, of their proactive participation in continuing professional development and their commitment to experiential learning about these issues.

There is no question that pediatricians have an important role to play in helping treat pediatric mental health concerns,[12,13] particularly as society’s needs in this area increase and in light of estimates that less than 20% of children and youth receive appropriate treatment.[14] However, CBCPs are increasingly the principal care providers for those with significant mental health needs and high burdens of care, despite persistent concerns that this level of complexity is far beyond their scope and that they are receiving variable—and often wholly inadequate—supports from community and subspecialist mental health providers. For example, the provincial Child and Youth Mental Health program, which is intended to provide comprehensive primary and secondary mental health services,[15] is hampered by long wait lists and a scarcity of providers and funding.[16] Further, the persistent shortage of child/adolescent psychiatrists[17] has significantly constrained subspecialty assessment, management, and longitudinal follow-up. The Compass program is a valiant attempt to maximize the resources that support community providers.[18] Yet even innovative programs like Compass may inadvertently increase the burden on CBCPs. Instead of being able to refer a patient directly to psychiatry, CBCPs must invest significant time and administrative costs to receive Compass advice about a patient that the psychiatrist has never seen. In turn, CBCPs remain responsible for the effective and safe implementation of the recommendations provided, even if they are beyond the CBCP’s scope, and their potential utility may go unrealized in a community setting due to a lack of available resources.

Ultimately, the lack of child/adolescent psychiatrists and robust community mental health infrastructure highlights critical gaps in our health care system, which are a concern in a high-income country where high-quality, equitable, and accessible health care is considered a social right.[19] Although CBCPs find themselves in the unenviable position of having to make up the deficit in care, many have found time to develop additional skills to address the need. This is a testament to their commitment to the children and youth they serve. Yet their ongoing efforts to address pediatric mental health concerns are having negative impacts on their personal well-being and professional longevity in community-based practice, which is threatening the sustainability of the community pediatric workforce.

Calls to action

How might we move forward? While we did not solicit participants’ ideas for improvement, our results nonetheless demand action to address their concerns. We offer four recommendations and two broader considerations that will help all interest holders move forward in ways that better provide the kind of mental health care that children and youth need and deserve.

First, we suggest that current wait times for psychiatric consultation should be reduced significantly and pathways for longitudinal care, rather than single consults, should be created. Specifically, it is important to establish a fast-track system for complex or refractory cases, where patients can be assessed by psychiatrists in an expedient manner if pediatricians are struggling after initial interventions or if Compass advice has proven insufficient.

Second, the Compass program, while well intentioned, needs to be reformed and enhanced to ensure consistent, effective support is provided. CBCPs should have direct access to psychiatrists rather than spending considerable time moving through multiple gatekeeping steps with intake workers.

Third, instead of forcing CBCPs to shoulder sole responsibility for the care of children with complex mental health needs, comprehensive and adequately funded team-based care models that foster seamless collaboration between family physicians, pediatricians, allied health care professionals, and psychiatrists must be put in place. Leveraging the experiences and drawing on the examples of both the Child and Youth Mental Health and Substance Use Community of Practice[20] and Foundry[21] may provide some concrete guidance on this front.

Fourth, large investments in primary and secondary child and youth mental health services are long overdue, echoing others’ calls for “right-sizing” children’s health care systems and for mental health to be a key pillar of a pan-Canadian child health strategy.[4]

More broadly, we also highlight two deeper considerations.

First, the Canada Health Act aims, in part, “to protect, promote and restore the mental well-being of residents of Canada.”[22] However, the narrow range of services that it compels provincial and territorial health insurance plans to provide includes only mental health services provided by physicians or in hospitals. As a result, there is significant heterogeneity in the kinds of mental health care services and prescriptions that are covered by various jurisdictions.[23] This frequently leads to substantial and prohibitive out-of-pocket costs for families in accessing counselors, psychologists, and therapists;[24] as a result, they have little recourse but to continue to seek help from physicians like CBCPs, whose services are free at the point of care. It is past time to update decades-old legislation to align with the mental health needs of Canadians in 2026 and for the public system to cover the cost of professionals whose training and purview are centred on mental health.

Second, given current concerns about mental health care delivery, it seems reasonable for departmental and educational leaders to improve pediatricians’ skill sets through training. For example, one current entrustable professional activity in pediatric residency focuses on “assessing and managing patients with mental health issues,”[25] yet residents need only two successful encounters in the community to pass this requirement. However, efforts to equip future CBCPs with expanded competencies to deliver complex mental health care risk reinforcing the very system of care delivery that created this problematic gap to begin with. Such measures may paradoxically delay urgently needed reform of child and youth mental health services, while implying that the current setup—which is already having significant negative impacts on CBCPs—is somehow acceptable or sustainable. Preparing trainees to take on more mental health care responsibilities does nothing to address the root causes of the issue and may leave CBCPs unfairly burdened with propping up a fragmented and underresourced system they did not create.

Study limitations

We did not explore any of the concerns identified by CBCPs in greater depth. In addition, our study’s BC-centric focus may limit its generalizability to other provincial and territorial jurisdictions, whose health care systems may differ in their organization and service offerings. Further, the reported trends in mental health care over time may be distorted by recall bias. Finally, although there was a response rate of nearly 30%, the CBCPs who did not respond may have different opinions from those reported. Therefore, our results may be skewed and may provide an inaccurate depiction of the current state of pediatric mental health care provided by CBCPs.

Conclusions

The mental health care needs of Canadian children and youth are increasing in both scale and complexity. CBCPs in BC are doing what they can in response, yet their personal well-being and professional longevity are being increasingly compromised by having to work beyond their scope and with insufficient supports from both primary and subspecialty mental health services. While our results represent only one snapshot of one jurisdiction, the current situation appears unsustainable and presents real threats to the long-term viability of the community pediatric workforce. As a result, we must move beyond short-term, reactive fixes that shift the burden of care onto CBCPs. Instead, we must commit to creating sustainable solutions that improve timely access to appropriate mental health care professionals, while also redesigning a mental health care system that is capable of providing the kind of care that Canadian children and youth need, when and where they need it, in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the British Columbia Pediatric Society Advocacy Committee for their thoughtful input on the design of this study.

Funding

No funding was provided, although the British Columbia Pediatric Society provided administration and data collection support.

Competing interests

None declared.

BOX. Exemplar quotations.

Supports from other services

Overall perceptions

- “I feel like I have no support.” (R75)

- “Absolutely terrible support and getting worse. A crisis.” (R87)

- “Poorly. Inefficient. I am not an intake worker. Why am I holding the bag? How has this happened? Nobody would design a system like this.” (R55)

Perceptions of community-based supports (e.g., Child and Youth Mental Health [CYMH])

- “CYMH exists in my community, but every patient who ever calls is told that their child doesn’t meet [the] criteria. . . . I would guess about 1% of the kids that we are following who have tried to access CYMH supports have ever actually seen a psychiatrist for help with medication options.” (R57)

- “CYMH continues to reject most ‘mild’ cases (including patients who are suicidal). . . . CYMH also does not seem to be able to provide adequate counseling/therapies for most patients. The lack of transparency of what CYMH is actually providing is a huge hindrance for working in the community.” (R91)

Perceptions of support from child and adolescent psychiatry consultative services

- “I do not feel well supported by psychiatry, in terms of both availability and helpfulness.” (R25)

- “I refer to psychiatry when patients are complex and often need longer-term follow-up. So, it is frustrating when they don’t see them more than once. . . . For example, I am not trained in or comfortable starting antipsychotics like aripiprazole. I do not feel that this is my role as a pediatrician.” (R47)

- “Psychiatry provides a good one-time consultation, but most of the cases I refer require ongoing follow-up . . . [and having the consult response offer] a list of medication options (e.g., ‘Try this, and if this doesn’t work, [you] can try this one, then add this one’) is not that helpful, as I often have no experience with any of the meds suggested.” (R66)

Perceptions of support from the Compass program (physician-to-physician virtual call support program)

- “Compass is helpful for very specific questions such as medications. For more complex questions around behavioral approaches, systems navigation, youth and family engagement, we need more hands-on support [rather] than a list of recommendations that are impossible to implement on our own.” (R65)

- “Compass has become more useful over the years. However, sometimes I just need somebody else to see the patient, not to base a diagnosis on my impression of what is going on. The drawback of only getting physician-to-physician advice is that I don’t know what I don’t know. I am only able to ask the patient what I know and then present to the consultant what I see, rather than have them actually assess patients for themselves and perhaps come up with a different conclusion.” (R70)

Comfort level and overall individual ability

- “I feel confident in my scope as a general pediatrician in managing cases of moderate severity and complexity. I am not confident—nor do I believe I should be—in providing care to highly complex psychiatric patients (e.g., repeated psychiatric admissions, polypharmacy, multiple comorbid diagnoses with social complexities).” (R44)

- “I have gotten better over the years at managing straightforward ADHD, anxiety, academic difficulties. But once you have medication failures, multiple meds, more complex mental health issues such as bipolar, substance use, eating disorders, a community clinic without access to mental health support is absolutely not enough.” (R59)

Professional and personal impacts

Impacts on overall well-being

- “The burden of caring for kids with such a high level of acuity of complex needs—behavioral and mental health—is exhausting, especially with so little community support. At least 30% of the kids I see need a team approach, family therapy, [cognitive-behavioral therapy] for kids, advocacy for school. And instead, they get one harried pediatrician trying to hold up the system.” (R29)

- “I’m tired and on the edge of burnout. . . . I feel dumped on—the subspecialist sees when the patient is in crisis, and recommendations are then made for the pediatrician to do a list of things. . . . There is no psych follow-up consistently offered.” (R52)

- “Very stressful. I often look at my list of appointments for the next day and start feeling anxious. I feel that I am not doing what I trained for.” (R68)

Impacts on professional longevity and practice sustainability

- “This is my main source of frustration in my office world. I have OFTEN contemplated how I could decline any more of these referrals to affect my own mental health and reduce burnout but do not think I can do this. Instead, I dream about quitting office practice . . . and I am not that old!” (R42)

- “It’s been extremely difficult, and I feel like I’ve had to put a lot of time to learn how to do this work with minimal support. It can be very demoralizing. And yes—it definitely makes me want to leave pediatrics.” (R53)

- “I almost left practice a year ago and have thought several times about moving to hospital-based work only. I was completely burned out.” (R83)

- “I will be leaving community practice and moving to a hospital clinical associate position. I often feel overwhelmed, unsupported, and out of my depth with my mental health/behavior patients. I was not trained to manage these patients through residency.” (R24)

- “I will retire ASAP because of this trend. It makes me hate my office a large proportion of time, and I feel helpless to change it.” (R87)

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, et al. Worldwide prevalence and disability from mental disorders across childhood and adolescence: Evidence from the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Psychiatry 2024;81:347-356. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5051.

2. Mental Health Commission of Canada. Growing together: Children and youth. Accessed 3 November 2025. https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/what-we-do/children-and-youth/.

3. Statistics Canada. 2023 Canadian health survey on children and youth—Changes in the mental health of respondents from the 2019 survey. 10 September 2024. Accessed 3 November 2025. www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/240910/dq240910a-eng.htm.

4. Conference Board of Canada. Nurturing minds for secure futures: Timely access to mental healthcare for children and youth in Canada. Ottawa: Conference Board of Canada, 14 December 2023. Accessed 14 November 2025. www.childrenshealthcarecanada.ca/media/0l0dg50s/nuturing-minds-for-secure-futures-2023-1.pdf.

5. Boak A, Hamilton HA, Adlaf EM, et al. The mental health and well-being of Ontario students, 1991–2017: Detailed findings from the Ontario Student Drug Use and Health Survey. CAMH Research Document Series No. 47. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2018. Accessed 14 November 2025. www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdf---osduhs/mental-health-and-well-being-of-ontario-students-1991-2017---detailed-osduhs-findings-pdf.pdf.

6. Wiens K, Bhattarai A, Pedram P, et al. A growing need for youth mental health services in Canada: Examining trends in youth mental health from 2011 to 2018. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci 2020;29:e115. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000281.

7. World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF. Mental health of children and young people: Service guidance. Geneva: WHO and UNICEF, 9 October 2024. Accessed 14 November 2025. www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240100374.

8. Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). Overall trends for child and youth mental health. Ottawa: CIHI, 1 May 2025 Accessed 3 November 2025. www.cihi.ca/en/child-and-youth-mental-health/overall-trends-for-child-and-youth-mental-health.

9. Canadian Paediatric Society. Strategic priorities: 2024–2027. 5 June 2025. Accessed 3 November 2025. https://cps.ca/en/strategic-priorities.

10. Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334-340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

11. CanREACH. Educating and empowering primary care providers to make and sustain practice changes in pediatric mental health. Accessed 3 November 2025. https://canreach.mhcollab.ca/.

12. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Objectives of training in pediatrics. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2008. Accessed 5 December 2025. https://royalcollege.ca/content/dam/documents/ibd/pediatrics/pediatrics_otr_e.pdf.

13. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Pediatric competencies, 2021, Version 1.0. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2020. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://royalcollege.ca/content/dam/documents/ibd/pediatrics/pediatrics-competencies-e.pdf.

14. Canadian Paediatric Society. Child and youth mental health. Policy brief. April 2022. Accessed 3 November 2025. www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/441/HESA/Brief/BR11751193/br-external/CanadianPaediatricSociety-e.pdf.

15. Government of British Columbia. Child and youth mental health. 9 June 2025. Accessed 3 November 2025. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/managing-your-health/mental-health-substance-use/child-teen-mental-health.

16. Canadian Mental Health Association British Columbia. Mental health for all: Building a comprehensive system of care in BC. Vancouver: Canadian Mental Health Association British Columbia, August 2024. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://bc.cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/CMHA-BC_Policy-Adovcacy-Roadmap_2024_08_30.pdf.

17. Child Health BC. Setting the stage: Mental health services for children and youth. Vancouver: Child Health BC, July 2019. Accessed 14 November 2025. www.childhealthbc.ca/sites/default/files/19_07_17_mh_su_setting_the_stage_2017_18_cihi_data.pdf.

18. Tsang VWL, Lin MCQ, Huang N, et al. Compass—Canada’s first child psychiatry access program: Implementation and lessons learned. PLoS One 2025;20:e0323199. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0323199.

19. Romanow RJ. Building on values: The future of health care in Canada—Final report. Ottawa: Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada, November 2002. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/CP32-85-2002E.pdf.

20. Shared Care Committee. Child and youth mental health and substance use (CYMHSU) community of practice. Accessed 3 November 2025. https://sharedcarebc.ca/our-work/spread-networks/cymhsu-community-of-practice.

21. Foundry. About us. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://foundrybc.ca/about-us/.

22. Canada Health Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6. 1985. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-6/page-1.html.

23. Martin D, Miller AP, Quesnel-Vallée A, et al. Canada’s universal health-care system: Achieving its potential. Lancet 2018;391(10131):1718-1735. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30181-8.

24. Lowe L, Fearon D, Adenwala A, Wise Harris D. The state of mental health in Canada 2024: Mapping the landscape of mental health, addictions and substance use health. Toronto: Canadian Mental Health Association, November 2024. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/CMHA-State-of-Mental-Health-2024-report.pdf.

25. Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Entrustable professional activities for pediatrics. Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, 2020. Accessed 14 November 2025. https://royalcollege.ca/content/dam/documents/ibd/pediatrics/epa-guide-pediatrics-e.pdf.

Dr Schrewe is an assistant professor in the Department of Pediatrics in the Island Medical Program; a scholar at the Centre for Health Education Scholarship, Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia; a member of the British Columbia Pediatric Society Advocacy Committee; and a community-based consultant pediatrician (ORCID: 0000-0001-9743-2894). Dr Tsai is a consultant pediatrician in South Surrey, BC, and the current chair of the British Columbia Pediatric Society Advocacy Committee. Dr Evoy is executive director of the British Columbia Pediatric Society/American Academy of Pediatrics–BC Chapter, in Vancouver, BC.

Corresponding author: Dr Brett Schrewe, brett.schrewe@ubc.ca.