Barriers to liver transplant preclinic access in British Columbia

ABSTRACT

Background: Vancouver General Hospital, the sole provider of adult liver transplants in British Columbia, faces increasing numbers of referrals. We examined potential areas for efficiency gain in its preclinic evaluation process.

Methods: This single-centre study included interviews with internal and external health providers and a retrospective analysis of all 112 liver transplants performed in 2023. Wait times were compared between outpatients and inpatients and between Vancouver Coastal Health and the other regional health authorities in BC: Fraser Health, Interior Health, Northern Health, and Island Health.

Results: In 2023, median wait times from referral to first consult were 87 days for outpatients (highest in the Interior Health Authority: 156 days) and 1 day for inpatients. Median evaluation times were 143 days for outpatients and 8 days for inpatients. Median referral to transplant times were 320 days for outpatients and 32 days for inpatients. Median referral to transplant times for outpatients were shortest in Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health and longest in Interior Health, followed by Northern Health and Island Health. Challenges to activation in the preclinic were attributed to the referral process, staffing, and resource allocation.

Conclusions: To meet increasing demand for adult liver transplants and improve efficiency, the preclinic requires additional clinic space, an online referral system, and better communication among health authorities.

Persistent regional disparities in access to liver transplantation highlights the need for localized and contextualized solutions to achieve timely and equitable care across the province.

Background

Liver transplantation remains the leading treatment for chronic liver failure; it extends survival and improves quality of life. Since 1989, the British Columbia Liver Transplant Program at Vancouver General Hospital (VGH) has been the province’s sole provider of adult liver transplants.[1] In 2023, the program performed 112 transplants, meeting increasing demand across BC’s five regional health authorities: Vancouver Coastal Health, Fraser Health, Interior Health, Northern Health, and Island Health.[2]

Transplant evaluation begins with a referral from the patient’s local health authority—typically submitted by an internist, hepatologist, or surgeon—and must include the necessary documents, scans, and tests. Referrals are then triaged based on urgency and are followed by interdisciplinary assessment at the VGH preclinic. Research on systemic barriers to liver transplantation has shown that longer wait times correlate with higher wait-list mortality and reduced access, particularly for patients in remote and resource-limited areas.[3-5] Programs in other regions have adopted day-case assessments and telehealth solutions to improve pretransplant processes, which have reduced costs and delays while maintaining patient satisfaction.[6,7] Additionally, the accelerated adoption of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted its potential to enhance health care delivery, although barriers such as limited technology access and low health literacy continue to impede equitable access.[8] These studies have demonstrated the importance of evaluating and streamlining pretransplant workflows to ensure timely and equitable care.

No studies have formally assessed the efficiency of liver transplant preclinic assessment, wait times for each component, or barriers at each stage. This study builds on previous research by systematically analyzing wait times, identifying region-specific barriers, and gathering qualitative insights from transplant team members and referring physicians across BC. By examining the preclinic workflow in this context, we aimed to provide actionable recommendations to improve efficiency, reduce delays, and enhance equitable access to liver transplantation in the province.

Methods

We used a mixed-methods approach that included interviews with internal and external health care providers and retrospective data collection. To be listed for transplant, referred patients typically have five consultations with a team that includes hepatology, hepatobiliary surgery, anesthesia, social work, and nutrition. Consultations with cardiology, dentistry, pharmacy, psychology, and addictions specialists are conducted in select cases. We interviewed all individuals involved in the assessment process, including a referring hepatologist from each health authority to gain provincial insight. Internal interviews explored staffing, workflows, service volumes, challenges, efficiency improvements, and departmental goals. External interviews with referring physicians similarly addressed referral completion, preclinic efficiency, and local and provincial improvement suggestions.

Following institutional approval from the University of British Columbia, we obtained a list of all 2023 liver transplant recipients. We selected 2023 because it was the most recent complete year of liver transplants. Notably, there were a historically high number of transplants in 2023.[2] Nontransplanted patients, including those declined or still under evaluation, were excluded.

Outpatients completed individual assessments without hospitalization, while inpatients underwent their entire workup during hospitalization, including those later discharged to home. Wait times were measured from clinic referral to consultation, except for specialist referrals, which were counted from the referral date. For inpatients transferred from other institutions, the referral date is usually the day the patient arrived at VGH.

Data collection was conducted at VGH using the Vancouver Coastal Health CST Cerner system for patient records. Data analysis was conducted in Excel, with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) calculated for all variables except age, for which means and standard deviations (SDs) were used. A permutation test for differences in medians was performed using Python to compare wait times between Vancouver Coastal Health and other regional health authorities, because it accounts for small sample sizes, unequal group distributions, and nonparametric data.

Results

Transplant volume and demographics

In 2023, 112 liver transplants were performed across all health authorities in BC; they included 109 initial transplants and 3 retransplantations that occurred within the same year. A patient from Yukon was excluded from the analysis, which resulted in 108 initial transplant recipients and 111 workups analyzed.

For outpatients at referral, the mean age was 57 years (SD: 11), the median MELD-Na score was 17 (IQR: 13,21), and the median Child-Pugh score was 8 (IQR: 6,10) [Table 1]. For inpatients at referral, the mean age was 51 years (SD: 13), the median MELD-Na score was 27 (IQR: 23,37), and the median Child-Pugh score was 11 (IQR: 10,12) [Table 1]. These findings suggest that inpatients had more advanced liver disease severity at the time of referral compared to outpatients, reflecting a population with higher acuity requiring hospitalization.

Wait times by patient type

Sixty-four percent of patients were assessed as outpatients. Across all health authorities, the median wait time for outpatients from referral to first consult was 87 days (IQR: 52,131), compared with 1 day (IQR: 0,44) for inpatients [Table 1]. The median time to complete assessment for activation was 143 days (IQR: 80,269) for outpatients and 8 days (IQR: 5,13) for inpatients [Table 1]. Overall, outpatients waited a median of 320 days (IQR: 246,509) to receive a liver transplant, whereas inpatients waited a median of 32 days (IQR: 13,77) [Table 1].

Regional disparities in overall wait times

Median wait times for outpatients from referral to transplant were similar in Vancouver Coastal Health (279 days [IQR: 160,320]) and Fraser Health (289 days [IQR: 230,572]) and were the lowest of the regional health authorities [Table 1]. The longest outpatient wait time from referral to transplant occurred in Interior Health (442 days [IQR: 306,572]), followed by Northern Health (426 days [IQR: 380,1189]) and Island Health (424 days [IQR: 320,561]) [Table 1]. Pairwise comparisons against Vancouver Coastal Health showed significantly longer median wait times in Interior and Island Health (P = .022 and P = .018, respectively) in receiving a liver transplant. These findings demonstrate notable regional disparities, with median wait times in Interior and Island Health approximately 5 months longer than in Vancouver Coastal Health. The absence of statistical significance in Northern Health may be partially attributable to the small sample size, which limits the power to detect differences despite the observed delays.

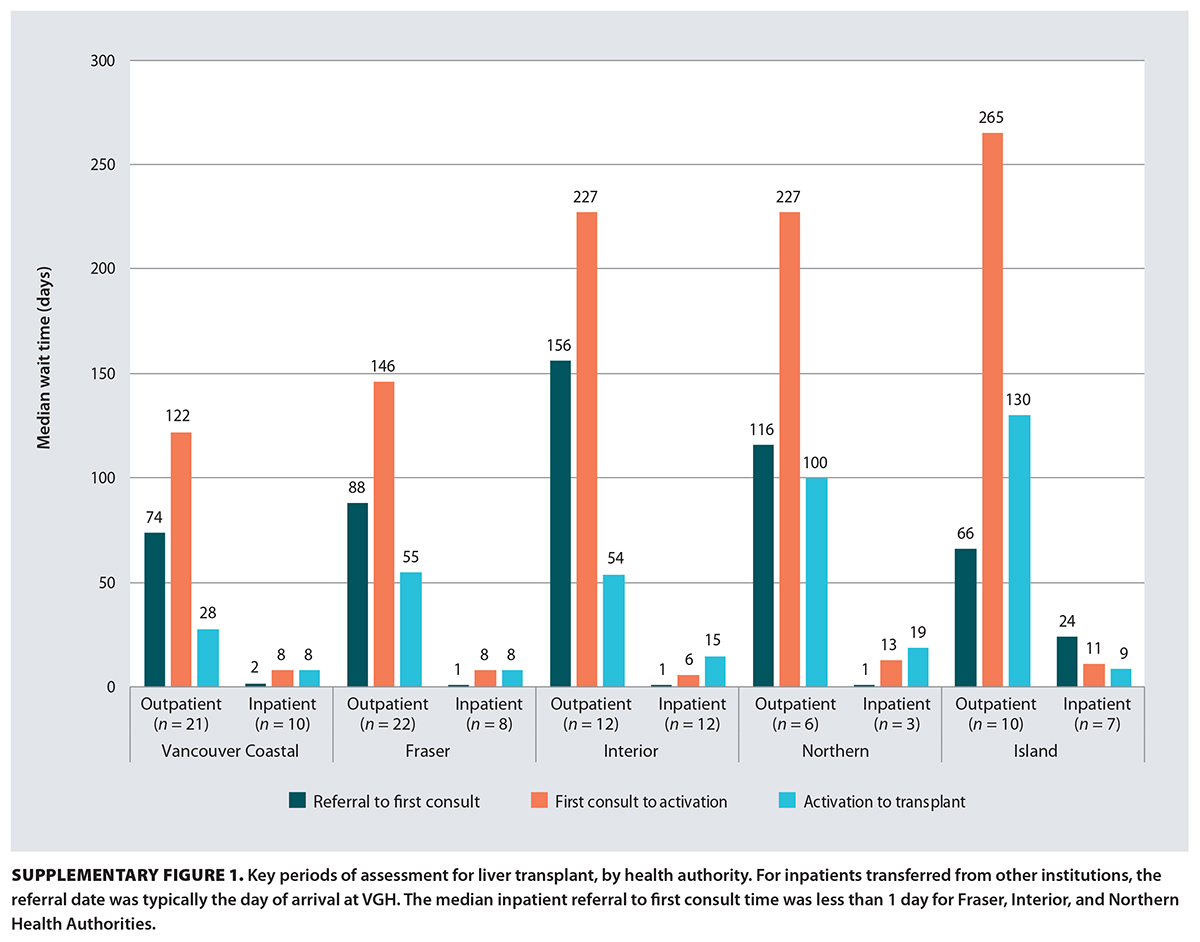

Regional disparities in stages of wait times

For outpatient referral to first consult, median wait times were significantly longer in Interior Health compared to Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .026), with a difference of 82 days; all other comparisons between Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health, Northern Health, and Island Health were not statistically different (P > .05). For outpatient first consult to activation, Interior Health and Island Health had longer wait times than Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .043 and P = .030, respectively). Similarly, in the outpatient activation to transplant stage, Island Health and Northern Health had longer wait times than Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .021 and P = .048, respectively). In contrast, for inpatients, there were no statistically significant differences across health authorities at any stage of the transplant process. Figure S1 shows the key periods of assessment and associated wait times, by health authority.

For outpatient referral to first consult, median wait times were significantly longer in Interior Health compared to Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .026), with a difference of 82 days; all other comparisons between Vancouver Coastal Health and Fraser Health, Northern Health, and Island Health were not statistically different (P > .05). For outpatient first consult to activation, Interior Health and Island Health had longer wait times than Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .043 and P = .030, respectively). Similarly, in the outpatient activation to transplant stage, Island Health and Northern Health had longer wait times than Vancouver Coastal Health (P = .021 and P = .048, respectively). In contrast, for inpatients, there were no statistically significant differences across health authorities at any stage of the transplant process. Figure S1 shows the key periods of assessment and associated wait times, by health authority.

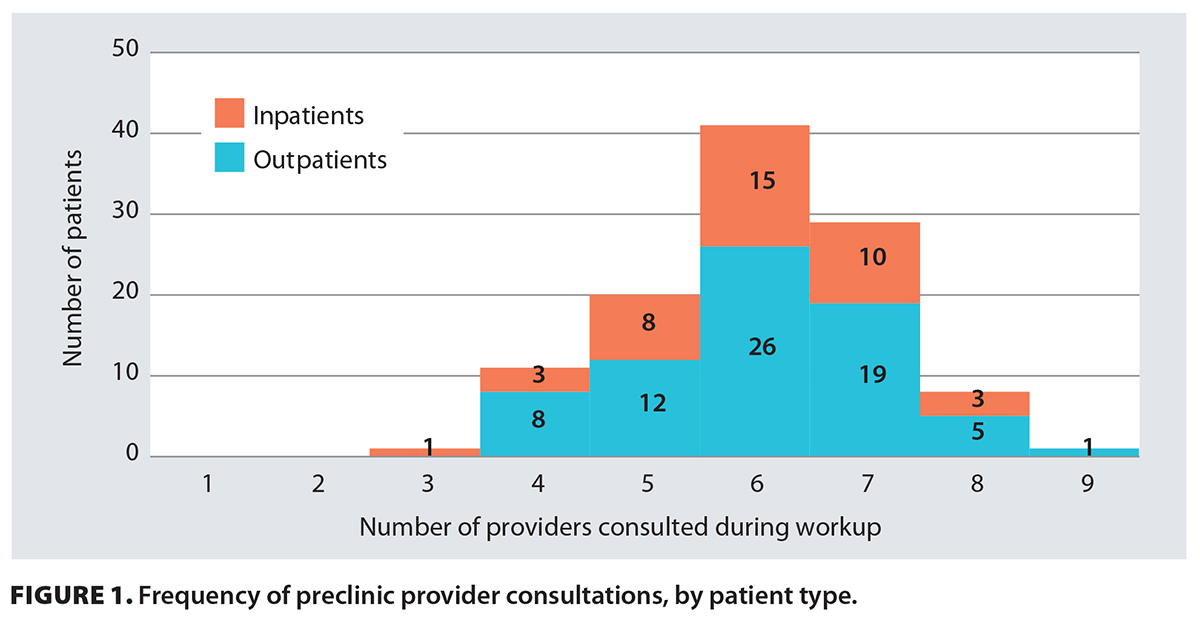

Figure 1 shows that most patients saw six or seven providers during their workup prior to activation, with consultations involving six providers being the most common overall. This indicates that additional specialist referrals were frequently required beyond the standard five consultations. For outpatients, notably long specialist referrals, in increasing order, were dentistry, social work, psychology, and pharmacy, suggesting that pharmacy consultations may be a significant source of delay for those who require them during their workup [Table 1]. Similarly, for inpatients, the order of increasing wait time was social work, pharmacy, psychology, and dentistry, suggesting that dentistry and psychology consultations may also be important contributors to inpatient delays [Table 1]. This pattern suggests that specialist consultations may be a key source of variability in workup duration, and that both regional disparities and the complexity of coordinating multiple referrals may substantially lengthen the transplant evaluation process.

Figure 1 shows that most patients saw six or seven providers during their workup prior to activation, with consultations involving six providers being the most common overall. This indicates that additional specialist referrals were frequently required beyond the standard five consultations. For outpatients, notably long specialist referrals, in increasing order, were dentistry, social work, psychology, and pharmacy, suggesting that pharmacy consultations may be a significant source of delay for those who require them during their workup [Table 1]. Similarly, for inpatients, the order of increasing wait time was social work, pharmacy, psychology, and dentistry, suggesting that dentistry and psychology consultations may also be important contributors to inpatient delays [Table 1]. This pattern suggests that specialist consultations may be a key source of variability in workup duration, and that both regional disparities and the complexity of coordinating multiple referrals may substantially lengthen the transplant evaluation process.

Internal interviews

Table 2 summarizes key barriers and proposed solutions identified by transplant team members, including nurse coordinators, program assistants, hepatobiliary surgeons, hepatologists, social workers, anesthesiologists, and dietitians. Key barriers included incomplete referral packages due to missing or delayed imaging, high administrative workload, patients arriving unprepared for consultations, delays in receiving signed forms, difficulty accessing prior test results, and limited clinic capacity. Proposed solutions included developing an online referral form with mandatory fields, hiring additional staff, creating educational resources to improve patient preparedness, providing the key forms earlier in the process, granting the transplant program provincewide image- and lab-ordering privileges, and expanding clinic space.

The referral package consists of a referral form and all necessary documentation describing the patient’s history and the indications for liver transplant assessment. This includes information on comorbidities, cardiac risk factors, and reports on recent blood work and imaging. To be assessed at VGH, the package must be complete, with all testing performed within the local health authority. Table 3 outlines the main components of the referral package and highlights items that are often incomplete or missing.

External interviews

All hepatologists identified delays and inefficiencies in VGH’s transplant referral process as major challenges, although long wait times were also shaped by region-specific factors.

In Fraser Health, improved communication with VGH has helped, but delays have persisted due to incomplete referral packages and restrictive cardiac testing policies, such as requiring cardiologist approval for myocardial perfusion imaging scans. Proposed solutions included clearer transplant status recognition and streamlined processes to improve patient flow.

In Interior Health, first consult wait times were the longest (up to 156 days) due to limited services in smaller communities. The local hepatologist emphasized that addressing this requires not only expanding VGH’s capacity but also adapting referral processes for patients with incomplete testing.

In Northern Health, geographic distances and socioeconomic challenges, especially for remote and First Nations communities, contributed significantly to delays. The hepatologist suggested tailoring referral requirements to each health authority’s unique challenges, with solutions such as establishing flexible processes, expanding local testing, and providing transportation support.

In Island Health, delays in cardiac testing and geographic isolation sometimes led to avoidable hospitalization. A triage system and rapid access clinic in Victoria have reduced hospitalizations and improved outcomes, but further refinements are needed.

Collectively, hepatologists stressed the need to expand VGH’s capacity, adopt more flexible referral processes, and address inefficiencies within each health authority to reduce wait times and meet growing transplant demands.

Discussion

The VGH liver transplant preclinic serves all of BC and has doubled the number of transplants performed over the last 12 years. A key driver of this success was increasing the clinic’s weekly capacity for new consults. This was achieved by mandating complete referral packages before submission, which allowed the identification of patients with contraindications to transplant at the time of triage and minimized the number of visits per patient before a decision for activation could be reached. By minimizing follow-ups and addressing incomplete referrals, the clinic significantly enhanced both efficiency and consult volume.

However, challenges have persisted, particularly in managing referral delays caused by incomplete submissions and systemic constraints. Many studies have highlighted health care disparities and disparities in access to liver transplantation related mostly to race and ethnicity,[9-13] but few have specifically examined the referral and evaluation stages.[14] Those that have focused on the referral stage identified barriers such as poor adherence to referral guidelines, provider biases, administrative delays, and poor coordination.[14,15] While our study did not indicate poor adherence to referral guidelines, it did identify administrative inefficiencies and poor coordination. Geographic and regional disparities in wait times were also evident. Similar to Madabhushi and colleagues, who highlighted how geographic isolation and limited specialist access hindered transplant access in rural areas,[16] we observed similar trends and increased wait times in underserved regions of BC.

Our findings demonstrated that outpatients experienced substantially longer wait times at each stage of the evaluation process compared to inpatients, with regional disparities contributing to median differences of up to 5 months. The need for multiple specialist consultations, particularly pharmacy, dentistry, and psychology referrals, also emerged as a possible factor prolonging workup durations.

Local preclinic challenges

Internally, incomplete referral packages and outdated fax systems, combined with difficulty tracking the status of required laboratory and imaging studies, continued to delay the scheduling of first consultations. Nurse coordinators often had to follow up to confirm whether essential tests were complete, adding to their administrative burden. Once patients were in clinic, additional challenges could arise during the evaluation process. They often stemmed from poor health literacy, inadequate social support, and geographic isolation.[17] Staffing shortages, particularly among social workers and dietitians, further exacerbated these issues by limiting the clinic’s ability to handle increasing patient volumes and provide comprehensive education. Insufficient clinic space also restricted patient flow. As a provincial service, the program would benefit from provincewide ordering privileges for labs and imaging, and the development of an online referral system that resets requirements by indication and can flexibly accommodate the unique challenges of each health authority.

Health authority–specific challenges

Geographic isolation in Northern Health and Island Health and inconsistent access to testing facilities in smaller communities, such as those in Interior Health, compounded delays. Socioeconomic barriers, particularly in remote and First Nations communities, complicated coordination efforts, which often required long-distance travel with limited support. McCormick and colleagues similarly noted that geographic proximity and financial barriers significantly affected access to liver transplantation, even within systems that offered universal health care.[18] Addressing these regional disparities necessitates expanding localized testing infrastructure—especially for cardiac and imaging services—and introducing transportation support for patients in underserved areas. Barritt and colleagues found that the number of gastroenterologists in a rural-referred patient’s health authority influenced transplant likelihood; that likelihood increased by 12% with each additional gastroenterologist per 100 000 population.[19]

Proposed solutions

To address the challenges identified in our study, we propose several solutions. Internally, increasing the number of hepatologists, expanding clinic space, and enhancing technological infrastructure are critical to reduce bottlenecks in first consults. Implementing an online referral system with mandatory fields tailored to specific indications could minimize incomplete submissions, although care must be taken to avoid overburdening referring physicians. Centralized tagging in CST Cerner for “Liver transplant” files could streamline workflows, and online educational videos could support patient education, particularly for those with encephalopathy. Investments in localized testing and transportation programs are also needed to reduce regional inequities. Addressing intraprovincial disparities will require coordinated efforts across all health authorities.

Study limitations

Our study is limited by the inherent challenges of retrospective chart reviews, including incomplete or missing records. Additionally, only patients who received liver transplants in 2023 were included; those who were referred but did not receive transplants that year were excluded. We interviewed only a small sample of referring physicians, and their answers may not reflect the opinions of other physicians. However, we included representation from each health authority, which provided a provincial perspective. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable metrics on the VGH liver transplant preclinic efficiency, integrates insights from referring physicians and allied health teams, and highlights wait times experienced by liver transplant recipients in 2023.

Conclusions

Patients experience major barriers to accessing liver transplantation in BC. Persistent regional disparities, driven by imaging delays, geographic isolation, and consultation bottlenecks, highlight the need for localized and contextualized solutions. Additionally, coordinated reforms to streamline the preclinic process are essential to advancing timely and equitable care across the province. Future research should evaluate the impact of these solutions and explore additional strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Competing interests

None declared.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the physicians and allied health care team members for their time and insights during the interviews, as well as the referring hepatologists for their valuable input and collaboration. Special thanks to our clinical research manager Ms Do Hee Kim, and pretransplant liver coordinator Ms Dionie DeLaFuente, for their instrumental support throughout the project. Artificial intelligence–assisted technologies were used to improve the readability and grammar of some text in this article without introducing generative content. All content in this article is original, based on our findings.

This article has been peer reviewed.

|

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. |

References

1. BC Transplant. Clinical guidelines for liver transplantation: Continuum of patient care from pre-transplant to post-transplant/out-patient. 2023. Accessed 27 January 2025. www.transplant.bc.ca/Documents/Health%20Professionals/Clinical%20guidelines/BC%20Clinical%20Guidelines%20for%20Liver%20Transplantation%20Jan%202023.pdf.

2. BC Transplant. Hundreds of people in British Columbia received the gift of life in 2023 thanks to a record number of organ donors [news release]. 29 January 2024. Accessed 27 January 2025. www.transplant.bc.ca/about/news-stories/organ-donation-transplant-stories/hundreds-of-people-in-british-columbia-received-the-gift-of-life-in-2023-thanks-to-a-record-number-of-organ-donors.

3. Hogen R, Lo M, DiNorcia J, et al. More than just wait time? Regional differences in liver transplant outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma. Transplantation 2019;103:747-754. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000002248.

4. Tuttle-Newhall JE, Rutledge R, Johnson M, Fair J. A statewide, population-based, time series analysis of access to liver transplantation. Transplantation 1997;63:255-262. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007890-199701270-00014.

5. Webb GJ, Hodson J, Chauhan A, et al. Proximity to transplant center and outcome among liver transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2019;19:208-220. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.15004.

6. Robinson Smith P, Richardson A, Macdougall L, et al. Changing the liver transplant assessment process from inpatient to a day-case and outpatient approach to reduce inpatient bed utilisation. BMJ Open Qual 2024;13:e002693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjoq-2023-002693.

7. Al Ammary F, Concepcion BP, Yadav A. The scope of telemedicine in kidney transplantation: Access and outreach services. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2021;28:542-547. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ackd.2021.10.003.

8. Rogers JL, Kraft K, Johnson W, Forbes RC. Adoption of telehealth as a strategy for pre-transplant evaluation and post-transplant follow-up. Curr Transplant Rep 2024;11:140-152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-024-00443-7.

9. Mathur AK, Ashby VB, Fuller DS, et al. Variation in access to the liver transplant waiting list in the United States. Transplantation 2014;98:94-99. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.TP.0000443223.89831.85.

10. Bryce CL, Angus DC, Arnold RM, et al. Sociodemographic differences in early access to liver transplantation services. Am J Transplant 2009;9:2092-2101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02737.x.

11. Nguyen GC, Thuluvath PJ. Racial disparity in liver disease: Biological, cultural, or socioeconomic factors. Hepatology 2008;47:1058-1066. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22223.

12. Nephew LD, Serper M. Racial, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2021;27:900-912. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.25996.

13. Mathur AK, Schaubel DE, Gong Q, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in access to liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2010;16:1033-1040. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.22108.

14. Julapalli VR, Kramer JR, El-Serag HB. Evaluation for liver transplantation: Adherence to AASLD referral guidelines in a large Veterans Affairs center. Liver Transpl 2005;11:1370-1378. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20434.

15. Yilma M, Kim NJ, Shui AM, et al. Factors associated with liver transplant referral among patients with cirrhosis at multiple safety-net hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2317549. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.17549.

16. Madabhushi VV, Wright M, Orozco G, et al. A qualitative study of end-stage liver disease and liver transplant referral practices among primary care providers in nonurban America. J Rural Health 2025;41:e12871. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12871.

17. Rosenblatt R, Lee H, Liapakis A, et al. Equitable access to liver transplant: Bridging the gaps in the social determinants of health. Hepatology 2021;74:2808-2812. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31986.

18. McCormick PA, O’Rourke M, Carey D, Laffoy M. Ability to pay and geographical proximity influence access to liver transplantation even in a system with universal access. Liver Transpl 2004;10:1422-1427. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.20276.

19. Barritt AS 4th, Telloni SA, Potter CW, et al. Local access to subspecialty care influences the chance of receiving a liver transplant. Liver Transpl 2013;19:377-382. https://doi.org/10.1002/lt.23588.

Mr Turner is a general surgery research assistant in the Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, and a chemistry BSc candidate at UBC. Dr Kim is a liver transplant and hepatopancreatobiliary surgeon and a clinical associate professor in the Division of General Surgery, Department of Surgery, UBC. Dr Chahal is a gastroenterologist and hepatologist and a clinical assistant professor in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, UBC. Dr Cox is a general internist based in British Columbia. Dr Yoshida is a gastroenterologist and hepatologist and a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, UBC. Dr Marquez is a gastroenterologist and hepatologist and a clinical associate professor in the Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, UBC.