ABSTRACT: Gastric ischemia secondary to infection by Sarcina ventriculi is rare and has been reported in a limited number of case studies. We describe the case of a patient who presented after a low-velocity motor vehicle accident with no symptoms. During his workup, a CT scan incidentally found the patient had portal venous gas and a focus of gastric wall ischemia, despite being asymptomatic. He underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which showed patchy necrosis but no perforation. He was managed conservatively with antibiotics and bowel rest. Biopsy showed the presence of S. ventriculi. A repeat CT scan with oral contrast and an esophagogastroduodenoscopy did not show any leak, and the patient was progressed to a full diet and discharged with oral antibiotics. This case showed that initial conservative management of S. ventriculi in hemodynamically stable patients, even in patients with gastric ischemia and necrosis, can be considered in the absence of perforation.

Initial conservative management of Sarcina ventriculi in hemodynamically stable patients, even those with gastric ischemia and necrosis, can be considered in the absence of perforation.

Sarcina ventriculi is a gram-positive anaerobic bacterium with a characteristic tetrad morphology.[1,2] It is technically part of the Clostridium genus and is therefore occasionally referred to as Clostridium ventriculi.[3] Case reports of the presence of S. ventriculi in the stomach often describe resultant symptoms of delayed gastric emptying, with cases of perforation also noted.[1] We describe the case of a patient who had gastric wall necrosis, extensive air in the portal vein system, and a biopsy that showed the presence of S. ventriculi.

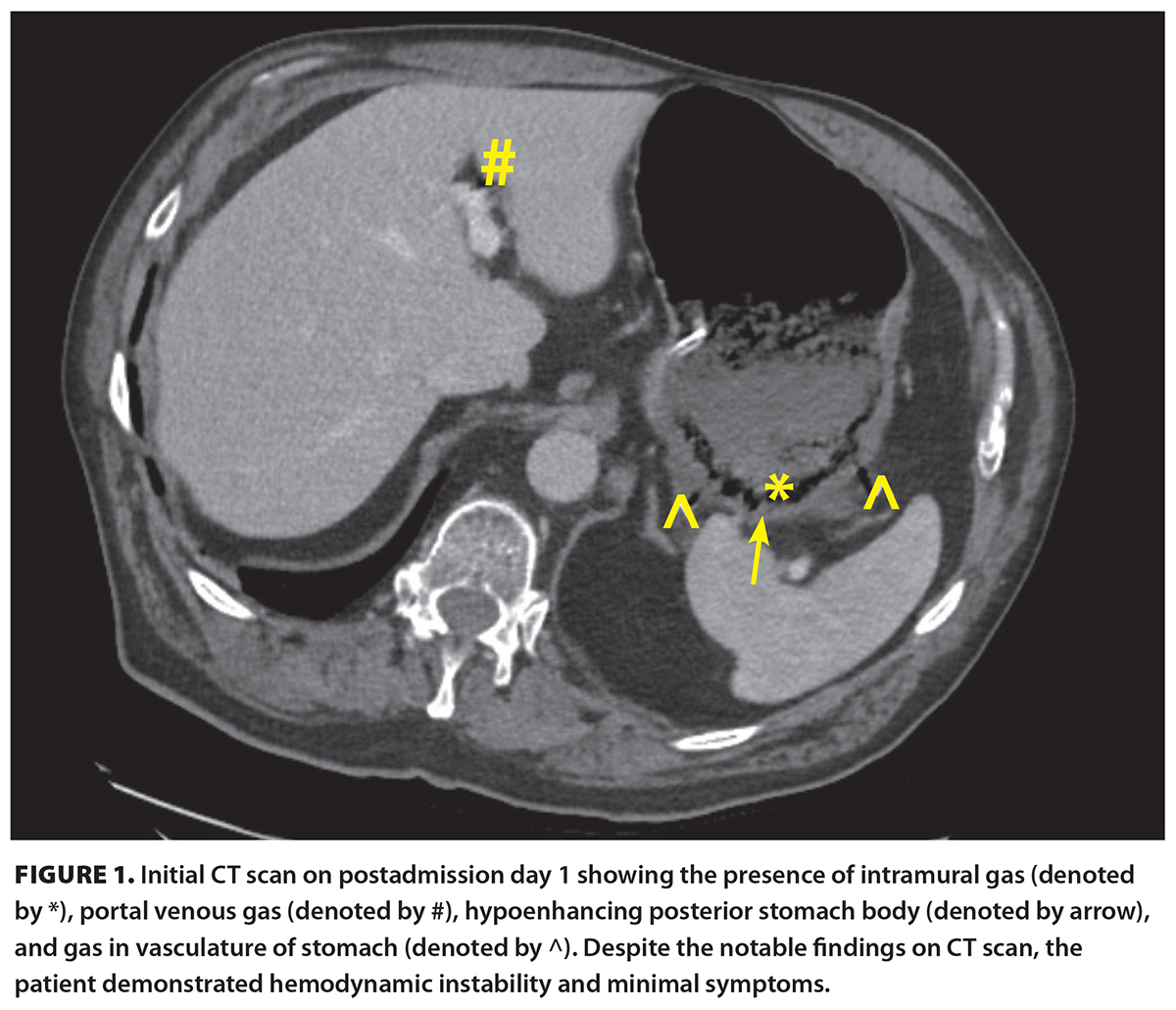

[11]A 71-year-old male presented to a peripheral centre with chest pain and shortness of breath after a low-velocity motor vehicle accident. His medical history was significant for previous myocardial infarction with stents in situ, hypertension, dyslipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had an 80-pack-year smoking history and was otherwise functionally independent. Cardiac workup was negative, and he was presumed to have a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. A CT scan of the abdomen was performed [Figure 1 [11]] in the context of the recent motor vehicle accident and new chest pain. Incidentally, the CT showed hypoenhancement of the posterior gastric wall with intramural air, gas extending along the right and left gastroepiploic veins, and portal venous gas. There was adjacent inflammation without any significant free fluid.

[11]A 71-year-old male presented to a peripheral centre with chest pain and shortness of breath after a low-velocity motor vehicle accident. His medical history was significant for previous myocardial infarction with stents in situ, hypertension, dyslipidemia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. He had an 80-pack-year smoking history and was otherwise functionally independent. Cardiac workup was negative, and he was presumed to have a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. A CT scan of the abdomen was performed [Figure 1 [11]] in the context of the recent motor vehicle accident and new chest pain. Incidentally, the CT showed hypoenhancement of the posterior gastric wall with intramural air, gas extending along the right and left gastroepiploic veins, and portal venous gas. There was adjacent inflammation without any significant free fluid.

The patient was hemodynamically stable and minimally symptomatic. Prior to transfer to our centre, the patient had a nasogastric tube inserted and was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor. He remained well during transfer and had minimal tenderness on abdominal examination. Laboratory investigations revealed a normal white blood cell count and mildly elevated C-reactive protein (21 mg/L). On arrival, the general surgery team saw the patient. He was alert, appeared well, and had a benign abdominal exam without tenderness. Given his clinical stability, he was taken for an esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which showed a 5 cm area of ulceration and necrosis with surrounding inflammatory changes, with no clear evidence of full thickness perforation [Figure 2 [12]]. Biopsies were taken.

Given the patient’s ongoing hemodynamic stability, benign examination, and no clear evidence of perforation on either CT or esophagogastroduodenoscopy, he continued to be managed nonoperatively. He was taken for a repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy the following day, which showed the lesion was similar in size and mucosa seemed to be slightly less necrotic. A CT scan with oral contrast was done 2 days later, which again did not show evidence of frank perforation. Peri-gastric inflammation had also decreased, and there was no longer presence of gas in the gastroepiploic or portal veins.

The patient was then progressed to a full diet, which he tolerated. At that time, pathology returned, showing the presence of luminal S. ventriculi. Additionally, biopsies showed chronic active gastritis with erosion and ulceration; no dysplasia, metaplasia, or malignancy; and equivocal results for Helicobacter pylori immunostaining. The infectious diseases service was consulted, and due to the possibility of gastric necrosis secondary to S. ventriculi, the patient was treated empirically with ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily and metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 10 days.

Follow-up with the patient as an outpatient was conducted several weeks later. He remained well. An outpatient esophagogastroduodenoscopy was arranged and was normal, and repeat biopsies of the gastric body failed to demonstrate the ongoing presence of S. ventriculi.

S. ventriculi is normally found as spores in soil, water, and air,[4] and it causes similar gastrointestinal presentations in veterinary medicine as in humans.[5] It may exert its pathologic effects via the accumulation of acetaldehyde from its metabolism.[6] This bacterium has been seen in patients with and without prior gastric surgery, and presentations have ranged from duodenal mass to gastroparesis to perforation.[1] It has also been seen in specimens associated with malignancy, including gastric adenocarcinoma.[1] It is unclear what determines the various degrees of symptomatology associated with infection.

We observed a case associated with a localized area of gastric necrosis with intramural air and gastroepiploic and portal vein gas. While we were not able to definitively rule out an additional or alternative cause, similar case reports seem to support that the pathogen may have played a contributory role.[7] Given that the stomach is a well-perfused organ, ischemia is rare and is usually due to vascular causes, systemic hypoperfusion, or mechanical obstruction.[8] Differential diagnosis for this patient’s localized gastric ischemia included a focal vascular event, especially in the context of the patient’s smoking history and medical comorbidities. Although we did not have a CT with arterial contrast, there were no obvious calcifications of the blood supply, and the patient did not describe a history consistent with chronic mesenteric ischemia, so we thought this was less likely. The ischemia could also have been due to trauma from the motor vehicle accident, but the accident lacked sufficient force to cause injuries to any adjacent structures (e.g., rib fractures, splenic injury). Given the lack of another rationale for the gastric ischemia, the bacterium was thought to be the culprit rather than an incidental finding. While not all patients with gastric ischemia require operative management, such findings should prompt monitoring, additional workup and consideration of endoscopy, and follow-up to ensure resolution. Operative indications can include gastric volvulus failing endoscopic management and gastric or mesenteric ischemia causing hemodynamic instability. Thus, cases of gastric ischemia should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.[8] The patient in this case study did not have a definitive reason for operative intervention; thus, we pursued conservative management, and there was complete resolution of the patient’s endoscopic, pathologic, and radiographic findings with antimicrobial therapy.

This case is unique and highlights that certain patients with active S. ventriculi infection without pneumoperitoneum or hemodynamic instability could be nonoperative candidates. Although the literature suggests that those with perforation associated with S. ventriculi gastric infection have a poor prognosis,[9] it is mixed for those without frank perforation. In one case report, an 86-year-old female with nonperitonitic pain, elevated lactate, and leukocytosis was taken for an exploratory laparotomy, and imaging showed extensive portal vein gas and gastric emphysema.[10] There was no frank perforation, and no resection was performed at the time of operation; intraoperative endoscopy revealed necrotic gastritis. Postoperatively, the patient was managed with antibiotics, and repeat imaging within 24 hours showed significant improvement of imaging findings; thus, there may be a role for nonoperative management. This is further supported by a case report of a 3-year-old patient who presented with hematemesis and leukocytosis, and X-rays showed massive gastric dilation with intramural air.[11] The patient was managed with endoscopic decompression and antimicrobial treatment, and there was significant improvement of endoscopic findings on repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Because S. ventriculi can persist despite antimicrobial treatment, even up to 4 weeks after treatment,[12] repeat esophagogastroduodenoscopy should be considered to ensure clearance. Conversely, there was a report of an 86-year-old patient who presented with diffuse nonperitonitic pain, and investigations showed elevated lactate, extensive portal vein gas, and gastric emphysema; the patient died during resuscitation, prior to any operative management.[13] Notably, the diagnosis of S. ventriculi infection may not be readily available at the time of initial management or during the early resuscitation period.

This case report includes details on imaging, the extent of infection, and our management of the case, which may be of use to clinicians in similar scenarios. However, our results cannot be generalized, because this is a case study that lacks comparisons to other patients. Many reports lack a control group; hence, it is difficult to identify the optimal management for patients with S. ventriculi, because their presentation and prognosis can vary significantly.

Nonetheless, this case report suggests that patients with S. ventriculi infection should be managed on a case-by-case basis, ideally in a setting with access to overnight surgical and endoscopic capabilities. Close follow-up of biopsy results, with documented clearance of S. ventriculi infection, is warranted to avoid progression to perforation.

S. ventriculi can present in both outpatient and inpatient settings, and presentations associated with radiographic or endoscopic findings of ischemia should warrant close observation and treatment. Patients without gastric perforation or hemodynamic instability can be trialed for nonoperative management on a case-by-case basis with monitoring. Posttreatment investigations should be performed to ensure bacterial clearance.

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

[13] [13] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [13]. |

1. Marcelino LP, Valentini DF, dos Santos Machado SM, et al. Sarcina ventriculi a rare pathogen. Autops Case Rep 2021;11:e2021337. https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2021.337 [14].

2. Ratuapli SK, Lam-Himlin DM, Heigh RI. Sarcina ventriculi of the stomach: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:2282-2285. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2282 [15].

3. Willems A, Collins MD. Phylogenetic placement of Sarcina ventriculi and Sarcina maxima within group I Clostridium, a possible problem for future revision of the genus Clostridium. Request for an opinion. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994;44:591-593. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-44-3-591 [16].

4. Lowe SE, Pankratz HS, Zeikus JG. Influence of pH extremes on sporulation and ultrastructure of Sarcina ventriculi. J Bacteriol 1989;171:3775-3781. https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.171.7.3775-3781.1989 [17].

5. Vatn S, Gunnes G, Nybø K, Juul HM. Possible involvement of Sarcina ventriculi in canine and equine acute gastric dilatation. Acta Vet Scand 2000;41:333-337. https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03549642 [18].

6. Al Rasheed MRH, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: Review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2016;140:1441-1445. https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2016-0028-RS [19].

7. Savić Vuković A, Jonjić N, Bosak Veršić A, et al. Fatal outcome of emphysematous gastritis due to Sarcina ventriculi infection. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2021;15:933-938. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518305 [20].

8. Sharma A, Mukewar S, Chari ST, Wong Kee Song LM. Clinical features and outcomes of gastric ischemia. Dig Dis Sci 2017;62:3550-3556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4807-4 [21].

9. Dumitru A, Aliuş C, Nica AE, et al. Fatal outcome of gastric perforation due to infection with Sarcina spp. A case report. IDCases 2020;19:e00711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00711 [22].

10. Alvin M, Al Jalbout N. Emphysematous gastritis secondary to Sarcina ventriculi. BMJ Case Rep 2018;2018:bcr2018224233. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-224233 [23].

11. Laass MW, Pargac N, Fischer R, et al. Emphysematous gastritis caused by Sarcina ventriculi. Gastrointest Endosc 2010;72:1101-1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.021 [24].

12. Sopha SC, Manejwala A, Boutros CN. Sarcina, a new threat in the bariatric era. Hum Pathol 2015;46:1405-1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.021 [25].

13. Singh K. Emphysematous gastritis associated with Sarcina ventriculi. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2019;13:207-213. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499446 [26].

Dr Jatana is a general surgery resident in the Department of Surgery at the University of Alberta. Dr Hintz is a clinical assistant professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of British Columbia and a general surgeon at Abbotsford Regional Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Sukhdeep Jatana, sjatana@ualberta.ca [27].

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/node/11007

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/sukhdeep-jatana-mdcm

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/graeme-hintz-md-frcsc-med

[4] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No10_sarcina-ventriculi.pdf

[5] https://bcmj.org/print/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina

[6] https://bcmj.org/printmail/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina

[7] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[8] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Successful nonoperative management of gastric ischemia and portal venous gas secondary to Sarcina ventriculi infection&url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[9] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[10] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[11] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No10_sarcina-ventriculi_Figure1.jpg

[12] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No10_sarcina-ventriculi_Figure2.jpg

[13] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[14] https://doi.org/10.4322/acr.2021.337

[15] https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i14.2282

[16] https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-44-3-591

[17] https://doi.org/10.1128/jb.171.7.3775-3781.1989

[18] https://doi.org/10.1186/BF03549642

[19] https://doi.org/10.5858/arpa.2016-0028-RS

[20] https://doi.org/10.1159/000518305

[21] https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-017-4807-4

[22] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00711

[23] https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-224233

[24] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.021

[25] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humpath.2015.05.021

[26] https://doi.org/10.1159/000499446

[27] mailto:sjatana@ualberta.ca

[28] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176?arturl=/articles/successful-nonoperative-management-gastric-ischemia-and-portal-venous-gas-secondary-sarcina&nodeid=67

[29] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop