ABSTRACT

Background: Assessing patient satisfaction, particularly among patients with complex disability, is vital to patient-centred care and access to care. We evaluated patient satisfaction at the BC Children’s Hospital Spinal Cord Clinic using the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18), modified to suit our pediatric population.

Methods: The modified PSQ-18 was distributed to families who visited the Spinal Cord Clinic from June to October 2019. Seven domains of patient satisfaction were assessed: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with doctor, and accessibility and convenience. Likert scale data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Two independent evaluators analyzed additional qualitative feedback.

Results: During the study period, 231 families visited the Spinal Cord Clinic; 80 participated in the study. Patients and families reported the highest degree of satisfaction with interpersonal manner and communication and the lowest satisfaction with financial aspects and accessibility and convenience. Participants also provided comments about their clinic experiences.

Conclusions: Families were generally satisfied with their clinical care and aspects under the control of health care providers. The clinic has conducted follow-up visits virtually when possible to reduce the financial burden of in-person appointments.

Offering patients a platform to express their level of satisfaction with their care can help care providers respond to areas of dissatisfaction and improve health outcomes.

Traditional hierarchical medical frameworks assumed physicians knew what was best for their patients and often left patients out of the decision-making process.[1] This medical model of care has been replaced with an increasingly patient- and family-centred model, where patients actively collaborate with their health care team to design and manage their treatment journey.[2] As a “desirable component of quality health care,”[3] the success of patient-centred care can be evaluated using tools such as patient satisfaction surveys and questionnaires.[4]

A variety of factors influence patient satisfaction. It has been positively correlated with trust in the health care team, interaction between doctors and patients, and perceived empathy of care providers.[5] The interpersonal skills of care providers[6,7] and wait times[7,8] also affect patient satisfaction and trust in the health care team. Other factors, such as lower socioeconomic status, have been negatively correlated with patient satisfaction.[9] In addition, patient satisfaction is positively correlated with treatment compliance[10,11] and positive health outcomes. Hence, evaluating patient satisfaction and eliciting feedback from patients helps care providers advocate for their patients’ needs, respond to areas of dissatisfaction, and improve health outcomes.

Because patient satisfaction is multifaceted, it is challenging to evaluate. Many instruments for assessing patient satisfaction, such as the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey[12] and the Long-Form Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-III),[13,14] target the adult patient group, None of these questionnaires were designed to target a pediatric outpatient population. Therefore, we chose a validated, fairly generic instrument, the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18), which we modified to suit our clinic situation. The PSQ-18 allowed us to assess parents’ and children’s satisfaction in seven domains: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with doctor, and accessibility and convenience.[15] The breadth of patient satisfaction domains assessed by the PSQ-18 sets it apart from other assessment tools. Moreover, the PSQ-18 is commonly cited in the literature[16] and has demonstrated versatility in diverse settings.[17-22] Consequently, we deemed the PSQ-18 to be a quick, easy, and comprehensive patient satisfaction questionnaire that was appropriate for a busy pediatric clinic setting.

We conducted this quality improvement project at the BC Children’s Hospital Spinal Cord Clinic, a multidisciplinary clinic that treats complex congenital and acquired spinal cord conditions, such as spina bifida, closed spinal dysraphism, VACTERL syndrome (VACTERL association), sacral agenesis, and traumatic and nontraumatic spinal cord injuries. As the designated provincial service for children with spinal cord conditions, the Spinal Cord Clinic serves an average of 260 patients living across BC. The combination of significant geographic distances and a sparse population creates unique challenges for health care delivery. An internal project conducted at the Spinal Cord Clinic indicated that 25.2% of patients live between 30 and 80 km from the clinic; 43.1% live more than 80 km from the clinic. Many of our patients experience limited mobility, and some are on ventilators, which exacerbates the challenges of traveling great distances for in-person appointments. Another internal study reported that approximately 25% of families in pediatric surgical clinics at BC Children’s live below the poverty line and experience many social vulnerabilities, which also affects patients’ ability to access care. Given the barriers to care our patient population experiences, ensuring our patients’ voices are heard and improving patient satisfaction are major priorities. We aimed to assess the various domains of patient satisfaction in our clinic’s vulnerable patient population to improve their health outcomes.

The Spinal Cord Clinic team designed this quality improvement project in conjunction with the Office of Pediatric Surgical Evaluation and Innovation. Because this was a quality improvement project, it was exempt from Research Ethics Board review, according to “TCPS 2 (2018) – Chapter 2: Scope and Approach.”[23]

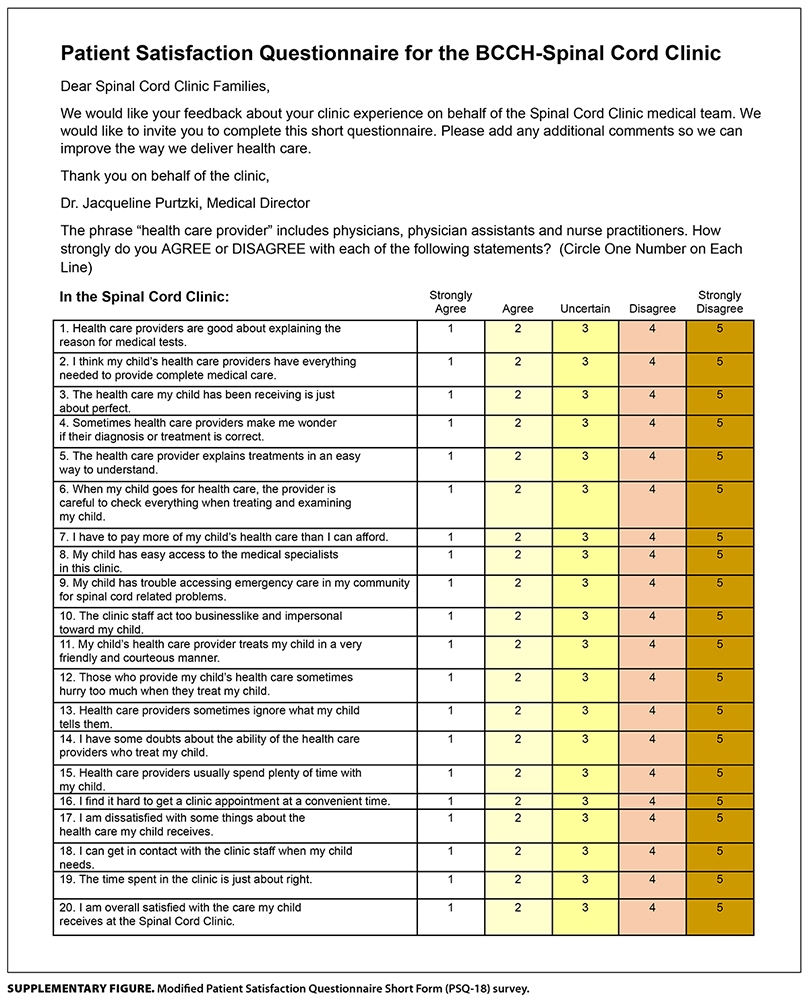

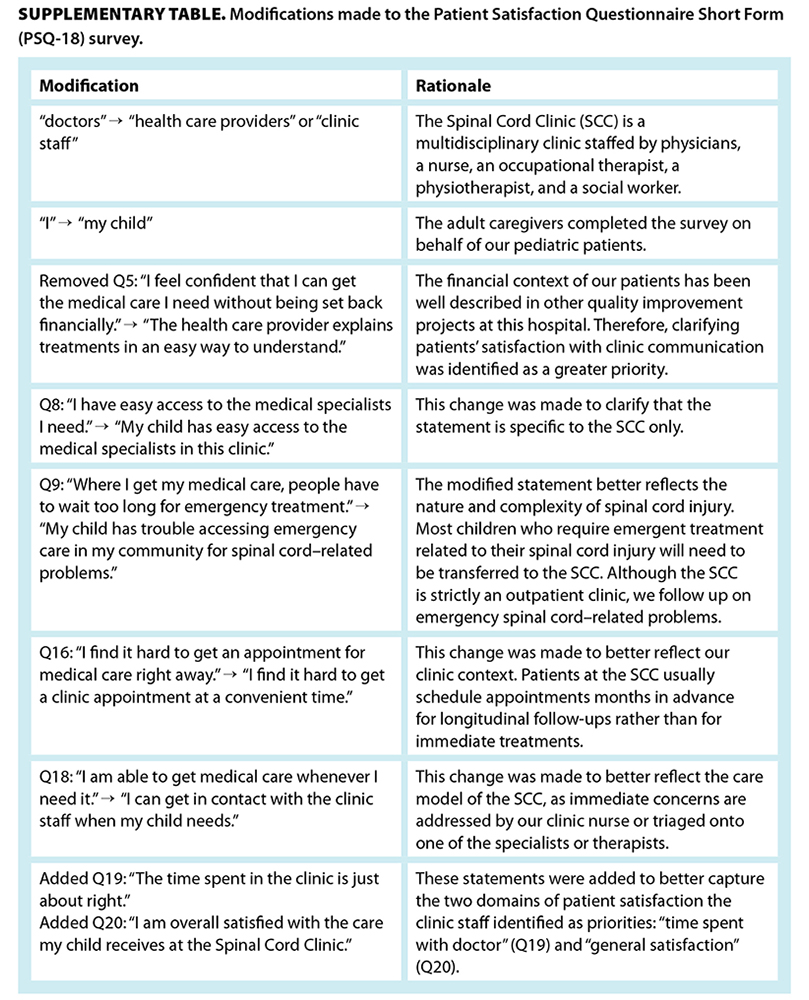

The PSQ-18 was originally developed using an English-speaking adult population.[15] Given our pediatric population and the multidisciplinary nature of the Spinal Cord Clinic, the research team modified the original PSQ-18 after careful review, prior to initiating the study. For example, the subject of each statement was changed from “I” to “my child,” because parents typically completed the survey. Additionally, a statement about financial considerations was replaced with one that focused on communication, because previous research had extensively examined the financial situation of clinic patients. We also added two statements to the PSQ-18 survey to fit the goals of our study and to reflect the nature of the pediatric outpatient clinic. The study team also added a comments section where participants could provide open-ended feedback. The modified PSQ-18 survey was available in English only.

The full questionnaire [12] and a comprehensive list of modifications and associated rationales [13] are reported in the supplementary files.

Patients who presented to the Spinal Cord Clinic from June to October 2019 were invited to complete the survey. Research assistants distributed printed surveys to patients and/or their caregivers after obtaining their informed consent. The survey included 20 statements.

Survey responses were transcribed and stored in a database in Microsoft Excel version 16.38 (Microsoft Corporation, 2020). Data were stored in a file encrypted with a password on a password-protected computer.

Likert scale data collected during the survey were processed using the methods outlined by Marshall and Hays.[15] Descriptive statistics, including ranges, means, medians, and modes, were calculated for each statement. Microsoft Excel was used to adjust responses so that a score of 5 indicated a strongly satisfied response, while a score of 1 indicated a strongly dissatisfied response. Next, the 20 statements were grouped into seven domains of patient satisfaction: general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with doctor, and accessibility and convenience. We defined technical quality as patients’ perceived competence of the specialists at the Spinal Cord Clinic. A Likert graph was created using R version 1.2.5033, 2019 (RStudio, PBC, 2019).

The qualitative responses patients left in the comments box were reviewed and coded by two research assistants (T.C. and C.B.) into positive or negative statements about the seven domains of patient satisfaction. Discussion between study team members resolved differences in comment classification between the two reviewers.

In total, 80 of 81 families (98.8%) that were invited to participate in the study completed the anonymous survey. This represented approximately 35% of the total clinic population (n = 231) and was deemed a representative sample of that population.

Table 1 [14] provides unadjusted scores for each survey statement. For eight of the 20 statements, experiences on both extremes of the “agreement” scale were reported, with at least one participant reporting “strong agreement” and another reporting “strong disagreement” with the same statement.

The Figure [15] shows the average score of responses in the seven domains of patient satisfaction. The greatest satisfaction was associated with “interpersonal manner” and “communication”; the lowest satisfaction was associated with “financial aspects” and “accessibility and convenience.”

In total, 28 comments were left in the comments box at the end of the survey; they included 25 positive and 25 negative statements [Table 2 [16]]. The greatest number of positive statements were made in the domain of “general satisfaction” (n = 12). The greatest number of negative statements were made in the domain of “accessibility and convenience” (n = 12).

To the best of our knowledge, the PSQ-18 survey has not been used in the setting of a pediatric spinal cord clinic, nor has it been used to evaluate clinics that share our multidisciplinary model of care. In our study, patients were encouraged to discuss their views of the Spinal Cord Clinic with their families and the clinic team. Providing pediatric patients with disability and their families with a platform to voice their opinions about their care contributes to the realization of Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.[24]

The modified PSQ-18 survey we used was well received by patients and families, as evidenced by its excellent response rate. Several key strengths contributed to its success. First, its concise yet comprehensive design allowed participants to complete it efficiently, even within their busy appointment schedules. Second, the survey encompassed broad patient satisfaction aspects, which enabled a holistic assessment of the care provided. Finally, the inclusion of a comments section empowered patients to share their experiences in their own words, which ensured their voices were heard and valued.

The patients and families at the Spinal Cord Clinic reported the greatest satisfaction in the domains of “interpersonal manner” and “communication,” the two domains over which the clinic has the most agency. Patients were most dissatisfied with “financial aspects” and “accessibility and convenience,” the domains over which the clinic has the least agency. In the open-ended comments, patients reported the most dissatisfaction with “accessibility and convenience” and the most satisfaction with “general satisfaction.” A caveat about the analysis of the open-ended comments is that the comments were not mandatory; therefore, not everyone left comments. As a result, the responses may not be representative of the entire group of participants in our study, let alone the entire clinic population.

Lower satisfaction in the domain of “accessibility and convenience” was not a surprise, because the Spinal Cord Clinic runs only 1 morning per week, and it serves a very large geographic area. There is little flexibility for families who are not available Thursday mornings. Scheduling conflicts with other clinics and the clinical responsibilities of the health care team outside of the Spinal Cord Clinic limit how responsive the team can be to concerns about accessibility and convenience of care. The PSQ-18 survey has been used in various studies in different settings, which demonstrates its versatility.[17-22,25,26] Other centres have also found that their patients reported the highest satisfaction with “interpersonal manner”[17] and the lowest satisfaction with “financial aspects”[17-19] and “accessibility and convenience.”[17] While it is important to note that those studies were conducted in different clinical and cultural contexts, there is an opportunity for health care providers in different settings to collaborate to create solutions to address relatively low satisfaction in common domains, such as “financial aspects” of care.

Dissatisfaction with the financial impact of care, which can act as an obstacle for patients attending appointments, is often overlooked. Many families must travel a long distance to attend the Spinal Cord Clinic. Out-of-town patients may have to stay overnight in Vancouver, either with relatives or in hotels, and their caretakers may need to take time off work and pay for their overnight stay, transportation, food, and parking. Significant personal expenses, combined with socioeconomic hardship, may make attending the clinic a serious affordability issue. Some parents qualify for government or social service support because they live below the poverty line, but many are not eligible for additional financial support because their income is just above the cutoff for social services. This may explain parents’ dissatisfaction with the “financial aspects” of the Spinal Cord Clinic. However, this is not a factor the clinic can control directly, although we try to connect families with financial resources whenever possible.

We adapted the PSQ-18 to better align with the unique patient population and clinical setting of the Spinal Cord Clinic and to enhance the survey’s relevance and accuracy in assessing patient satisfaction; however, this may have influenced the questionnaire’s original validity.

Additionally, we approached 81 of the 231 patients (35%) in the clinic’s total patient population. While we invited patients who presented to the clinic consecutively to participate, our sample may not have been representative of all 231 patients and families. The reason for this is multifactorial. First, because this was the first study that assessed patient satisfaction at the Spinal Cord Clinic, we focused on determining whether the modified PSQ-18 survey was well suited to the clinic rather than on reaching a large sample size. Second, our recruitment was limited by logistical constraints and scheduling issues within the clinic. It was not feasible to recruit patients over the entire year. Patients attend the Spinal Cord Clinic with varying frequency, depending on their need. By using a shorter study interval, we were more likely to sample opinions from a different family at each clinic encounter.

Because the modified PSQ-18 survey is a general, multidisciplinary questionnaire, it did not allow for the assessment of patient satisfaction within specific medical specialties involved in patients’ care. In the future, developing specialty-specific statements could provide a more detailed evaluation of the quality of care delivered by each discipline. This refinement would offer deeper insights into areas for improvement at the clinic, which would ultimately enhance the patient experience.

Last, because this was a pilot project for quality improvement in the Spinal Cord Clinic, we did not collect socio-demographic information, such as sex, household income, and distance of residence from the clinic. This limited our ability to analyze our results further and to establish any association between demographic variables and the results. We plan to collect this information in future studies.

We intend to use our modified PSQ-18 survey for future quality improvement studies. We will aim to include a larger sample size to represent the number of patients at the Spinal Cord Clinic and will develop more discipline-specific statements to gain insight into patients’ perspectives on the care they receive from specific disciplines. We will also aim to collect socio-demographic information so our results can be more thoroughly analyzed.

Since this initiative was conducted, there have been significant disruptions to care provided at the Spinal Cord Clinic due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, there have also been many positive changes at the clinic. First, discussions are being held between the Spinal Cord Clinic team and the hospital operational leads on potential improvements to the clinic structure, including the possibility of providing an extra clinic day and adding more clinical team members. This large-scale change will help address the accessibility issue that patients in our study noted. Second, the clinic plans to use internal funds to establish a bursary program for patients with financial constraints, in response to patients’ dissatisfaction with financial aspects of attending the clinic. Last, virtual care using applications such as Zoom or Microsoft Teams has become much more acceptable since the pandemic, and the clinic team has pivoted to a hybrid model of in-person and virtual care. This has numerous potential benefits for the patient population, many of whom have difficulty ambulating. The Spinal Cord Clinic research team plans to launch another patient satisfaction quality improvement study as a follow-up to our initial project in 2019, this time focusing on patients’ satisfaction with the hybrid model of care. The assessment of patient satisfaction reported in this study serves as a record of our prepandemic baseline patient satisfaction. By continuing to monitor patient satisfaction, we will be able to identify the long-term impacts of increasing access to virtual care and future quality improvement initiatives.

Quality improvement is a continuous process that demands ongoing evaluation and follow-up to ensure patients’ needs and expectations are met. This study aimed to enhance care at the Spinal Cord Clinic by offering patients a platform to share their experiences. The modified PSQ-18 survey proved to be both adaptable and applicable across diverse health care settings, making it a valuable tool for assessing and improving patient satisfaction. We hope to see its adoption in other clinics to further advance patient advocacy and the delivery of patient-centred care.

Internal funding from the BC Children’s Hospital Spinal Cord Clinic was used to purchase gift cards to thank participants for their feedback. This project received no external funding.

None declared.

The authors’ work takes place on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), Stó:lō and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh), and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam) Nations.

The authors thank the patients, families, and staff who made this work possible, especially Katherine Vinokour and Meena Singhal, as well as Damian Duffy and the Office of Pediatric Surgical Evaluation and Innovation for their support and mentorship.

[17] [17] |

[18] [18] |

This article has been peer reviewed.

[19] [19] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [19]. |

1. Kilbride MK, Joffe S. The new age of patient autonomy: Implications for the patient-physician relationship. JAMA 2018;320:1973-1974. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14382 [20].

2. What is patient-centered care? NEJM Catalyst. Accessed 3 January 2024. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559 [21].

3. Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, Dearing KA. Patient-centered care and adherence: Definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20:600-607. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x [22].

4. The Health Foundation. Helping measure person-centred care. 1 March 2014. Accessed 30 June 2024. www.health.org.uk/publications/helping-measure-person-centred-care [23].

5. Lan Y-L, Yan Y-H. The impact of trust, interaction, and empathy in doctor-patient relationship on patient satisfaction. J Nurs Health Stud 2017;2:2. https://doi.org/10.21767/2574-2825.100015 [24].

6. Renzi C, Abeni D, Picardi A, et al. Factors associated with patient satisfaction with care among dermatological outpatients. Br J Dermatol 2001;145:617-623. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04445.x [25].

7. Hall MF, Press I. Keys to patient satisfaction in the emergency department: Results of a multiple facility study. Hosp Health Serv Adm 1996;41:515-533.

8. Bleustein C, Rothschild DB, Valen A, et al. Wait times, patient satisfaction scores, and the perception of care. Am J Manag Care 2014;20:393-400.

9. Haviland MG, Morales LS, Dial TH, Pincus HA. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with health care. Am J Med Qual 2005;20:195-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860605275754 [26].

10. Calnan M. Towards a conceptual framework of lay evaluation of health care. Soc Sci Med 1988;27:927-933. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90283-3 [27].

11. Harris LE, Luft FC, Rudy DW, Tierney WM. Correlates of health care satisfaction in inner-city patients with hypertension and chronic renal insufficiency. Soc Sci Med 1995;41:1639-1645. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00073-G [28].

12. Goldstein E, Farquhar M, Crofton C, et al. Measuring hospital care from the patients’ perspective: An overview of the CAHPS® Hospital Survey development process. Health Serv Res 2005;40:1977-1995. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00477.x [29].

13. Ware J, Snyder M, Wright W. Part A: Review of the literature, overview of methods, and results regarding construction of scales. In: Development and validation of scales to measure patient satisfaction with health care services: Volume I of a final report. NTIS Publication no. PB 288-329. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 1976.

14. Ware J, Snyder M, Wright W. Part B: Results regarding scales constructed from the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire and measures of other health care perceptions. In: Development and validation of scales to measure patient satisfaction with health care services: Volume I of a final report. NTIS Publication no. PB 288-330. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 1976.

15. Marshall GN, Hays RD. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18). P-7865. RAND Corporation, 1994. Accessed 30 June 2024. www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P7865.html [30].

16. Thayaparan AJ, Mahdi E. The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) as an adaptable, reliable, and validated tool for use in various settings. Med Educ Online 2013;18: 21747. https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.21747 [31].

17. Chander V, Bhardwaj AK, Raina SK, et al. Scoring the medical outcomes among HIV/AIDS patients attending antiretroviral therapy center at Zonal Hospital, Hamirpur, using Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire (PSQ-18). Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS 2011;32:19-22. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7184.81249 [32].

18. Vahab SA, Madi D, Ramapuram J, et al. Level of satisfaction among people living with HIV (PLHIV) attending the HIV clinic of tertiary care center in Southern India. J Clin Diagn Res 2016;10:OC08-OC10. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/19100.7557 [33].

19. Holikatti PC, Kar N, Mishra A, et al. A study on patient satisfaction with psychiatric services. Indian J Psychiatry 2012;54:327-332. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.104817 [34].

20. Ziaei H, Katibeh M, Eskandari A, et al. Determinants of patient satisfaction with ophthalmic services. BMC Res Notes 2011;4:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-7 [35].

21. Yildirim A. The importance of patient satisfaction and health-related quality of life after renal transplantation. Transplant Proc 2006;38:2831-2834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.162 [36].

22. Chan FWH, Wong RSM, Lau WH, et al. Management of Chinese patients on warfarin therapy in two models of anticoagulation service – a prospective randomized trial. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006;62:601-609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02693.x [37].

23. Government of Canada. TCPS 2 (2018) – Chapter 2: Scope and approach. In: Tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans. 2019. Accessed 30 June 2024. https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter2-chapitre2.html [38].

24. UNICEF. Convention on the rights of the child. Accessed 25 February 2025. www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text [39].

25. Ganasegeran K, Perianayagam W, Manaf RA, et al. Patient satisfaction in Malaysia’s busiest outpatient medical care. Scientific World Journal 2015;2015:714754. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/714754 [40].

26. Aung MN, Moolphate S, Kitajima T, et al. Satisfaction of HIV patients with task-shifted primary care service versus routine hospital service in northern Thailand. J Infect Dev Ctries 2015;9:1360-1366. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.7661 [41].

Dr Chae is an orthopaedic surgery resident at the University of British Columbia. Dr Binda is a general surgery resident at the University of Ottawa. Dr Purtzki is a pediatric physiatrist at BC Children’s Hospital and a clinical assistant professor at the University of British Columbia.

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/node/10878

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/taewoong-chae-md

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/catherine-joanne-binda-md

[4] https://bcmj.org/author/jacqueline-s-purtzki-md

[5] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_bcmd2b.pdf

[6] https://bcmj.org/print/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic

[7] https://bcmj.org/printmail/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic

[8] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic

[9] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Assessing patient satisfaction in the BC Children’s Hospital Spinal Cord Clinic&url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[10] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic

[11] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[12] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_SupplementaryFigure_post.jpg

[13] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_SupplementaryTable_post.jpg

[14] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_bcmd2b_Table1.jpg

[15] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_Figure.jpg

[16] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_Table2.jpg

[17] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_SupplementaryFigure.jpg

[18] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol67_No7_core-Spinal-Cord-Clinic_SupplementaryTable.jpg

[19] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[20] https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.14382

[21] https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.17.0559

[22] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00360.x

[23] http://www.health.org.uk/publications/helping-measure-person-centred-care

[24] https://doi.org/10.21767/2574-2825.100015

[25] https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04445.x

[26] https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860605275754

[27] https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(88)90283-3

[28] https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(95)00073-G

[29] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00477.x

[30] http://www.rand.org/pubs/papers/P7865.html

[31] https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.21747

[32] https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7184.81249

[33] https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2016/19100.7557

[34] https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.104817

[35] https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-7

[36] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.162

[37] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02693.x

[38] https://ethics.gc.ca/eng/tcps2-eptc2_2018_chapter2-chapitre2.html

[39] http://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text

[40] https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/714754

[41] https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.7661

[42] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176?arturl=/articles/assessing-patient-satisfaction-bc-childrens-hospital-spinal-cord-clinic&nodeid=67

[43] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop