Rural health data can be more effectively organized through the use of population catchments to facilitate needs-based planning and serve as a framework for research and quality improvement initiatives.

There has been a steady and progressive decline in support for rural health care across Canada, including in British Columbia, where many barriers have not been adequately addressed, including those related to patient transportation, scope of rural facility services, ratio of physicians to population, burnout among health care providers, and lack of adequate financial and social resources.[1-5] It is also generally recognized that research on rural health care “is limited, poorly funded, and not well coordinated, and it often fails to be used in informing health policy.”[1] The subsequent lack of valid rural-specific data makes it difficult to sustain appropriate and sustainable levels of rural health services in a rural generalist context.[6] Nonetheless, government resources, policies, and infrastructure continue to prioritize urban perspectives, with rural priorities falling to the wayside. To address the need for more effective rural health data organization, we propose the use of a needs-based catchment approach designed specifically for the rural context, which provides clarity and accountability and serves as a framework for quality improvement and research.

The emphasis on urban-centred policies can be seen clearly in the existing health-related data in Canada, which prioritizes a use-based reporting structure and access to specialist services—factors that do not reflect the reality of rural generalist health systems and service use.[4] Currently in BC, health data are organized across the province using nested geographic health boundaries aligned with regional health authorities. There are four levels of data stratification, with health authorities being the broadest health boundary. Each health authority is divided into health service delivery areas, which are further subdivided into multiple local health areas. Each local health area comprises one or more community health service areas.[7] Community health profiles, which compile demographic and health data, have been created for 195 community health service areas and 142 municipalities across the province.[8] While this provides a consistent approach across the province, there are significant limitations to their application in rural areas.

Community health service areas must cover the entire province, which means that they are often very large in rural areas and contain significant areas of unpopulated land and/or regions with low population density. Moreover, the boundaries of these areas do not always align with the natural catchments of rural communities. This limits the utility of these areas as geographic units for reporting rural health data, as there is a lack of linkage between health service facilities and the surrounding populations that naturally depend on each facility. Further, the specialist-oriented data that are predominant in the community health profiles, such as reports on the number of patients with renal failure or myocardial infarctions, limit the utility of community health service area data in a rural context, where generalist care is more common and generalist care measures are needed.[4,8]

[14]Catchments as a complementary approach

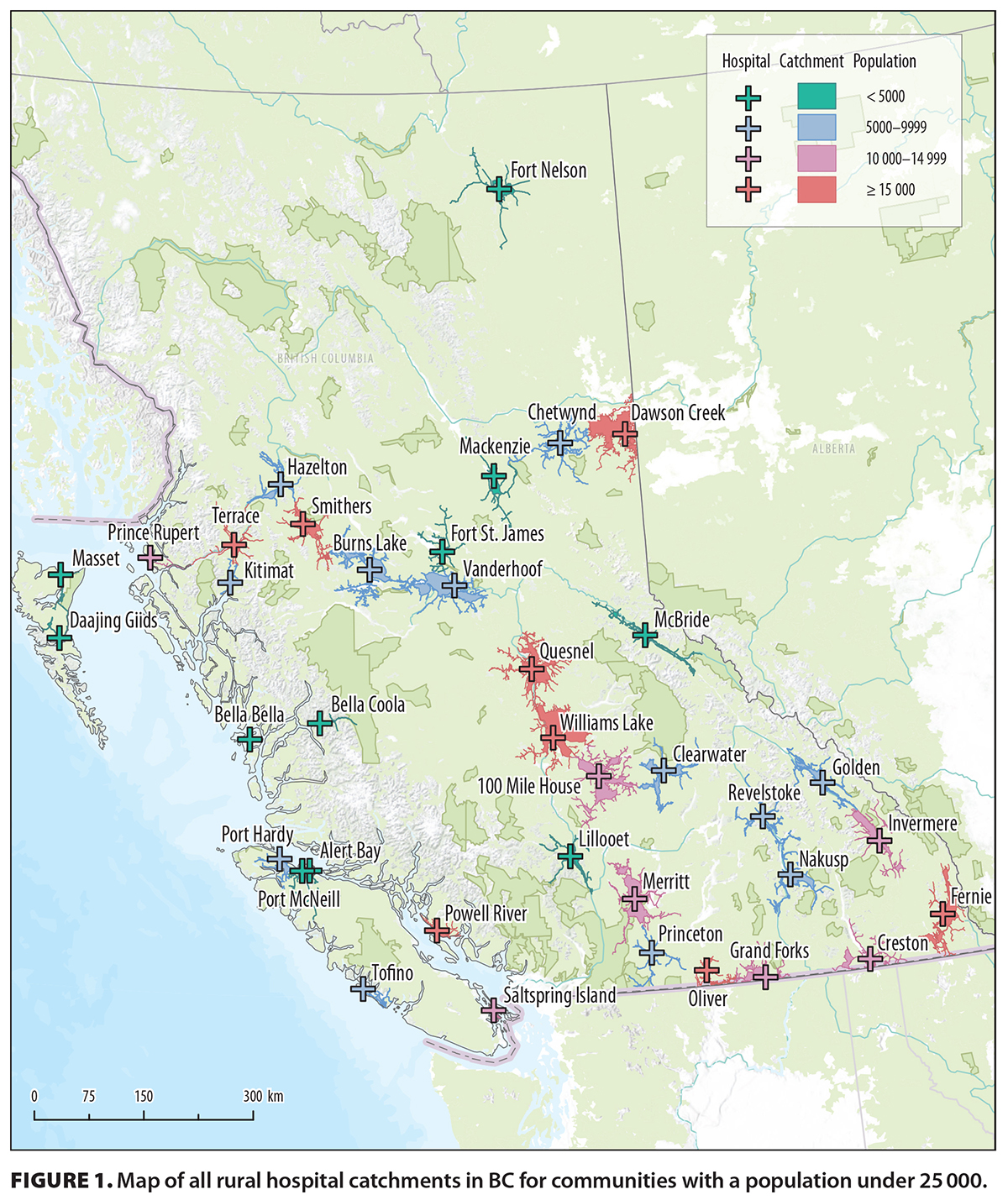

[14]Catchments as a complementary approachWe propose a complementary geographic approach to structuring rural health data, through population catchments. Broadly, a population catchment is the geographic area around a service point defined using criteria such as travel time or distance. The catchment population is then defined by the number of people living within that geographic area. Researchers have developed similar population catchments in other parts of the world, such as rural and remote Australia[9] and sub-Saharan Africa,[10] with similar objectives to increase the utility of rural health data and improve equity in services. We propose a population catchment approach for BC based on drive time to a given health care facility (in this case, rural hospitals). BC’s mountainous and coastal terrain lends itself to this catchment approach, as communities tend to be naturally separated from one another, making it clear which health facility rural residents are most likely to seek out. We intend this structure to be complementary to the overarching Ministry of Health geographic health boundaries that are mentioned above. To start, we have developed catchments based on a 1-hour drive time to a facility for all rural communities that contain a hospital and have a catchment population under 25 000 [Figure 1 [14]]. Catchments were created using ArcGIS Pro, and population estimates were derived from Canadian census data.

The goals of the population catchment approach are to build on the geographic characteristics of rural communities in BC and to define populations that naturally depend on local hospitals and associated services. Moreover, data that are structured on a catchment framework will provide a reasonably informed denominator for the catchment of a defined service facility, which will help facilitate improved needs-based planning accountability and quality improvement initiatives. A needs-based approach to health services planning, as opposed to one that is based on use, is better suited for rural communities because it allows health care systems to dynamically adapt to changes in population needs as they arise in the community.[11] Similarly, when health services do not prioritize population needs in the planning process, unmet needs may go unnoticed until they worsen and create greater undue stress for patients and the health care system as a whole.

Being able to define the catchment for a specific health facility also sets the stage for research examining the system’s efficacy and effectiveness. To this point, we have developed two needs-based measures and applied them to our rural catchments: the Rural Birth Index (RBI) and the Rural Generalist Provider Services Index (RGPSI). The RBI serves as an objective measure of population needs for birthing services, including surgical services,[12] and the RGPSI aims to quantify the need for rural generalist services at the community level. Demographic characteristics of the catchment can also be captured by combining the geographic catchment boundaries with other data sets, such as Canadian census data [Figure 2 [15]]. We compiled demographic data; our needs-based measures; and a variety of other information related to health services, referrals, transportation, and the environment into catchment profiles that can be used by rural health care providers, administrators, and community members. In this way, it is perhaps not unrealistic to imagine that through the transparency of understanding rural populations and the services that sustain them, we may have new ideas to apply across the larger health care system.

The principal limitation of our approach is that while it may work well for rural communities in a mountainous or coastal context, it loses focus as the population becomes more densely located and the terrain becomes more navigable. Therefore, we propose a population catchment approach specifically designed for rural communities of fewer than 25 000 people located in areas where communities have natural separation. While 1 hour is a reasonable amount of time to travel to a facility to receive care and provides a standard measure allowing for comparison between rural communities, it may not fully depict the realities of each community. Therefore, in addition to the standard 1-hour catchments, we are interested in expanding to create secondary catchments, tailored to specific communities.

Finally, because health service data are a moving target, it is challenging to constantly provide up-to-date data. To address this limitation, it is imperative that local providers have access to data related to their communities and that they have the ability to update these data on an ongoing basis.

Rural areas have the advantage of being able to naturally group the local population into distinct community catchments, which provides the opportunity to link the needs of the population with the services that can meet those needs, providing clarity, accountability, research opportunity, and a quality improvement framework. It is time we bring in the data infrastructure that is capable of serving the needs of rural communities.

None declared.

hidden

[16] [16] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [16]. |

1. Wilson RC, Rourke J, Onadasan IF, Bosco C. Progress made on access to rural health care in Canada. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:31-36.

2. Centre for Rural Health Research. Relocation for solid organ transplant: Patient experience and costs. 2024. Accessed 9 April 2025. https://med-fom-crhr.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2025/02/HIH_FINAL_REPORT_DEC19-copy.pdf [17].

3. McDonald B, Livergant RJ, Binda C, et al. Availability of surgical services in rural British Columbia. BCM 2024;66:51-57.

4. Grzybowski S, Kornelsen J. Rural health services: Finding the light at the end of the tunnel. Healthc Policy 2013;8:10-16.

5. Stronger BC. Good lives in strong communities: Investing in a bright future for rural communities. 2023. Accessed 29 July 2024. https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/Good-Lives-Strong-Communities-2023.pdf [18].

6. Rourke J, Bradbury-Squires D. Rural research: Let’s make it happen! Can J Rural Med 2022;27:116-117. https://doi.org/10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_4_22 [19].

7. BC Ministry of Health. BC Ministry of Health geographies portal. 2022. Updated March 2023. Accessed 17 July 2024. https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/5f44ce2df1e2471b8570f1a2ba2801a6/ [20].

8. Provincial Health Services Authority. BC community health data. Accessed 23 July 2024. http://communityhealth.phsa.ca/ [21].

9. McGrail MR, Humphreys JS. Spatial access disparities to primary health care in rural and remote Australia. Geospat Health 2015;10:138-143. https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2015.358 [22].

10. Macharia PM, Ray N, Giorgi E, et al. Defining service catchment areas in low-resource settings. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e006381. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006381 [23].

11. Murphy GT, Birch S, Mackenzie A, et al. An integrated needs-based approach to health service and health workforce planning: Applications for pandemic influenza. Healthc Policy 2017;13:28-42. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2017.25193 [24].

12. Grzybowski S, Kornelsen J, Schuurman N. Planning the optimal level of local maternity services for small rural communities: A systems study in British Columbia. Health Policy 2009;92:149-157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.007 [25].

hidden

Ms Kelly is a geographic information systems analyst for the Rural Health Services Research Network of BC. Ms Dunn is a research assistant for the Rural Health Services Research Network of BC. Ms Kim is a network coordinator for the Rural Health Services Research Network of BC. Dr Grzybowski is the network director for the Rural Health Services Research Network of BC.

Corresponding author: Dr Stefan Grzybowski, stefan.grzybowski@ubc.ca [26].

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/cover/januaryfebruary-2026

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/sarah-kelly-ba

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/theresa-asha-dunn-bsc

[4] https://bcmj.org/author/esther-kim-mph

[5] https://bcmj.org/author/stefan-grzybowski-md-ccfp

[6] https://bcmj.org/node/11060

[7] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_premise.pdf

[8] https://bcmj.org/print/premise/rural-data-amplification-linking-needs-rural-population-catchments-health-services-british

[9] https://bcmj.org/printmail/premise/rural-data-amplification-linking-needs-rural-population-catchments-health-services-british

[10] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/premise/rural-data-amplification-linking-needs-rural-population-catchments-health-services-british&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[11] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Rural data amplification: Linking the needs of rural population catchments to health services in British Columbia&url=https://bcmj.org/print/premise/rural-data-amplification-linking-needs-rural-population-catchments-health-services-british&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[12] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/premise/rural-data-amplification-linking-needs-rural-population-catchments-health-services-british&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[13] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[14] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_premise_Figure1.jpg

[15] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_premise_Figure2.jpg

[16] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[17] https://med-fom-crhr.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2025/02/HIH_FINAL_REPORT_DEC19-copy.pdf

[18] https://news.gov.bc.ca/files/Good-Lives-Strong-Communities-2023.pdf

[19] https://doi.org/10.4103/cjrm.cjrm_4_22

[20] https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/5f44ce2df1e2471b8570f1a2ba2801a6/

[21] http://communityhealth.phsa.ca/

[22] https://doi.org/10.4081/gh.2015.358

[23] https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006381

[24] https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpol.2017.25193

[25] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.03.007

[26] mailto:stefan.grzybowski@ubc.ca

[27] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176

[28] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop