ABSTRACT

Background: Health care disparities in rural and remote British Columbia have persisted over time despite efforts to improve access to care. While strategies have typically focused on improving access to primary care, discrepancies in access to specialist care remain uncertain. The aim of this study was to better understand the temporospatial distribution of general specialists in BC.

Methods: Clinician data were acquired from BC Ministry of Health Medical Services Plan reports for 2010–11 to 2022–23. The number of internal medicine specialists, pediatricians, and psychiatrists registered in each Health Service Delivery Area was analyzed over time.

Results: In 2022–23, 1480 internal medicine specialists, 364 pediatricians, and 864 psychiatrists were registered in BC. Only 6% to 7% of specialists were registered in rural and remote areas, a pattern that has persisted despite increases in clinician numbers since 2010–11.

Conclusions: Rural–urban discrepancies in specialist distribution in BC have persisted over the past decade. We call upon clinicians and policymakers to address this long-standing issue.

In 2022–23, only 6% to 7% of internal medicine specialists, pediatricians, and psychiatrists were registered in rural and remote areas, straining patients, family physicians, emergency services, and surgical specialties.

Health care disparities in rural and remote regions of British Columbia are well documented in the literature.[1,2] Despite efforts to close the gap, such as the creation of rural medical school training streams, health care inequities persist.[1,3,4] In recent decades, significant efforts have focused on addressing the shortage of primary care physicians in rural BC.[4,5] However, with advances in medicine, an aging population, and the increasing complexity of patients across the whole spectrum of age, specialists play a key role in the care of rural patients.[6]

Rural–urban health care inequities span medical fields, including internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry. In BC, only 40 pediatricians live and practise in rural communities, and the vacancy rate for pediatrician postings in rural communities has been 25% to 30% for several years.[7,8] Northern BC continues to face challenges recruiting pediatricians, despite the population having the highest percentage of children of any region in the province. Rural communities also experience worse mental health outcomes and, in particular, disproportionately higher suicide rates than urban centres.[9,10] Individuals in rural communities experience additional unique mental health needs compared with people in urban centres due to economic hardship associated with living in resource-centred towns, privacy concerns in seeking psychiatric help in small communities, and lack of outreach services.[9,11] The situation is further complicated by the current opioid crisis, where BC has double the rate of opioid toxicity compared with the national average.[12] Additionally, rural patients often face complex logistical challenges and financial and psychological consequences when they have to travel long distances to seek specialist services that are unavailable in their community.[13] The lack of access to specialists also strains primary care providers, emergency services, and surgical specialists such as obstetricians, who may feel that they need to practise outside their scope to address immediate patient needs.[2]

In recent years, innovative solutions to address health care needs have included the use of telemedicine and increasing outreach or mobile clinical services.[13,14] While some acute medical needs of BC’s rural patients may be supported by Real-Time Virtual Support (RTVS) services, such as the recently established Rural Outreach in Critical Care and Internal Medicine (ROCCi) and Child Health Advice in Real-Time Electronically (CHARLiE) hotlines, many of their acute and chronic health care needs are not being met.[14,15] Fly-in/fly-out services, locums, and telehealth options attempt to support regions in need, but wait times can be significant, and long-term care can be affected. As a result, patients may receive suboptimal treatment of complex chronic medical diseases, which places further strain on the health care system. These strategies do not replace the need for having on-the-ground specialists in many of BC’s larger rural communities.[9] In addition, rural specialists may face shortages of specialized equipment, support staff with enhanced training, and social services, which are needed to provide comprehensive services comparable to those in urban settings.[16]

Overall, access to specialists in rural BC is limited. The aim of this study was to better understand the temporospatial distribution of specialists in BC.

Physician data were acquired from BC Ministry of Health Medical Services Plan (MSP) reports for fiscal years 2010–11 to 2022–23.[17] Data were summarized for the following specialties because they represent some of the most common nonprocedural “general” specialists in rural communities: internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry.

The number of specialists per 100 000 persons was calculated using MSP registrants as a proxy for population. Data were analyzed for each Health Service Delivery Area (HSDA). The following HSDAs were deemed rural regions: East Kootenay, Kootenay Boundary, North Vancouver Island, Northwest, Northern Interior, and Northeast. The BC Rural Practice Subsidiary Agreement considers all communities in these regions as rural based on the following criteria: number of designated specialties within 70 km, number of general practitioners within 35 km, community size, distance from major medical community, degree of latitude, specialist centre, and location arc.[18] Data for physicians with unknown locality were excluded. Maps displaying the distribution of physicians in HSDAs and changes over time were created by the authors using QGIS (v. 3.34).

The numbers of physicians registered as practising “internal medicine” and “general internal medicine” were combined and reported as “general internists.” The number of physicians in the following internal medicine specialties were combined and reported as “subspecialists”: geriatrics, cardiology, rheumatology, clinical immunology and allergy, respirology, endocrinology, critical care, gastroenterology, nephrology, infectious diseases, hematology, and oncology. General internists and subspecialists were collectively referred to as “internal medicine specialists.” Subspecialists in psychiatry and pediatrics are not listed separately in the MSP register, so they were reported as “psychiatrists” and “pediatricians,” respectively.

In 2022–23, 1480 internal medicine specialists (439 general internists), 364 pediatricians, and 864 psychiatrists were practising in BC. Of these, 6% of internal medicine specialists, 7% of pediatricians, and 6% of psychiatrists were practising in rural HSDAs.

[16]Urban regions had more internal medicine specialists per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1A; supplementary materials are available from the corresponding author]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 65.4 internal medicine specialists and 49.2 subspecialists per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast region had 1.3 internal medicine specialists per 100 000 persons and no subspecialists [Supplementary Table 2]. Provincial medians were 19.0 internal medicine specialists and 11.7 subspecialists per 100 000 persons.

[16]Urban regions had more internal medicine specialists per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1A; supplementary materials are available from the corresponding author]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 65.4 internal medicine specialists and 49.2 subspecialists per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast region had 1.3 internal medicine specialists per 100 000 persons and no subspecialists [Supplementary Table 2]. Provincial medians were 19.0 internal medicine specialists and 11.7 subspecialists per 100 000 persons.

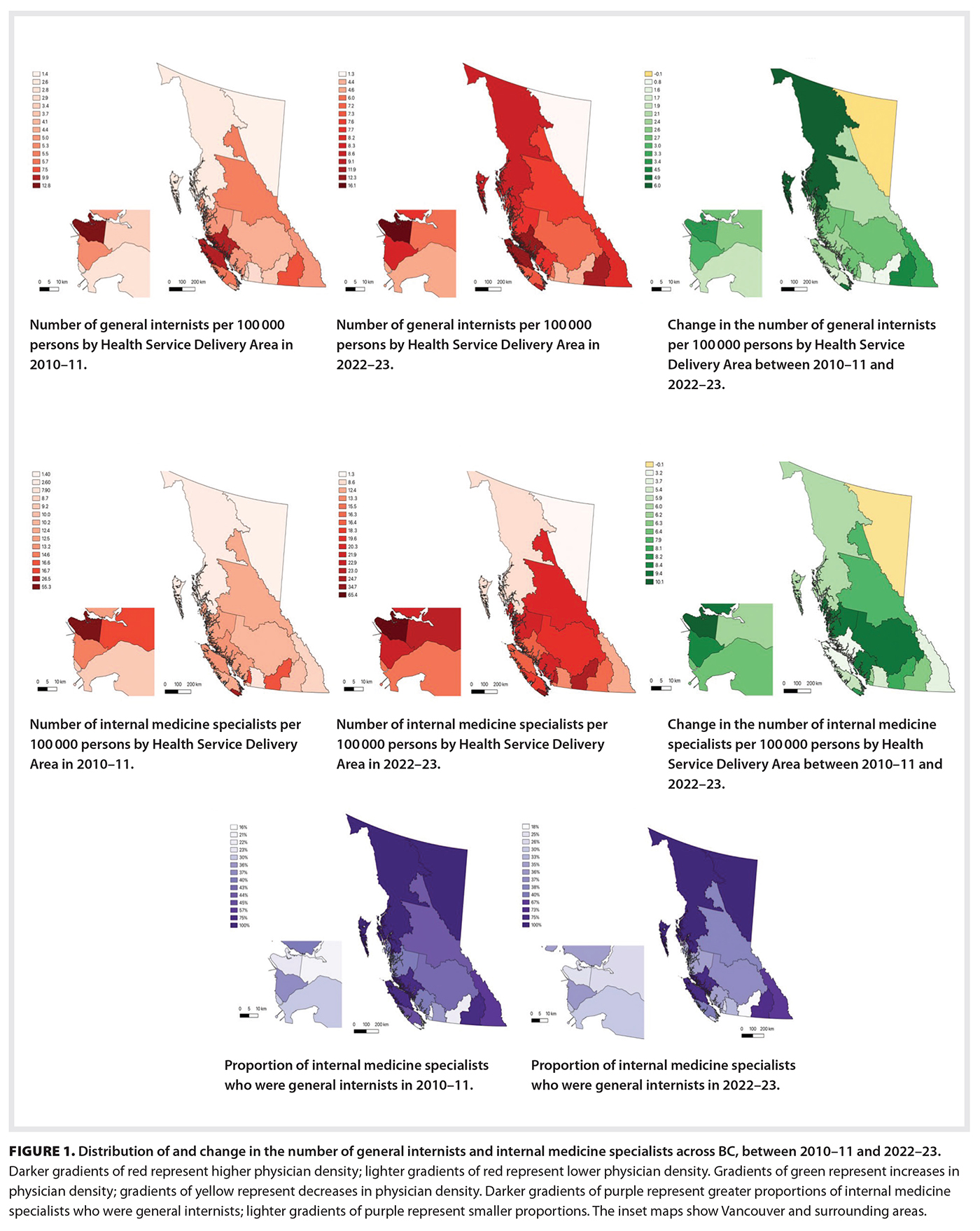

From 2010–11 to 2022–23, there was a 69% increase in the number of internal medicine specialists across all regions, with urban areas experiencing the greatest increase [Supplementary Table 3; Figure 1 [16]]. The number of internal medicine specialists per capita increased in all HSDAs except the Northeast. The greatest increases per capita occurred in urban regions (an increase of 10.1 in Vancouver versus 3.7 in the East Kootenay region and 3.2 in the North Vancouver Island region).

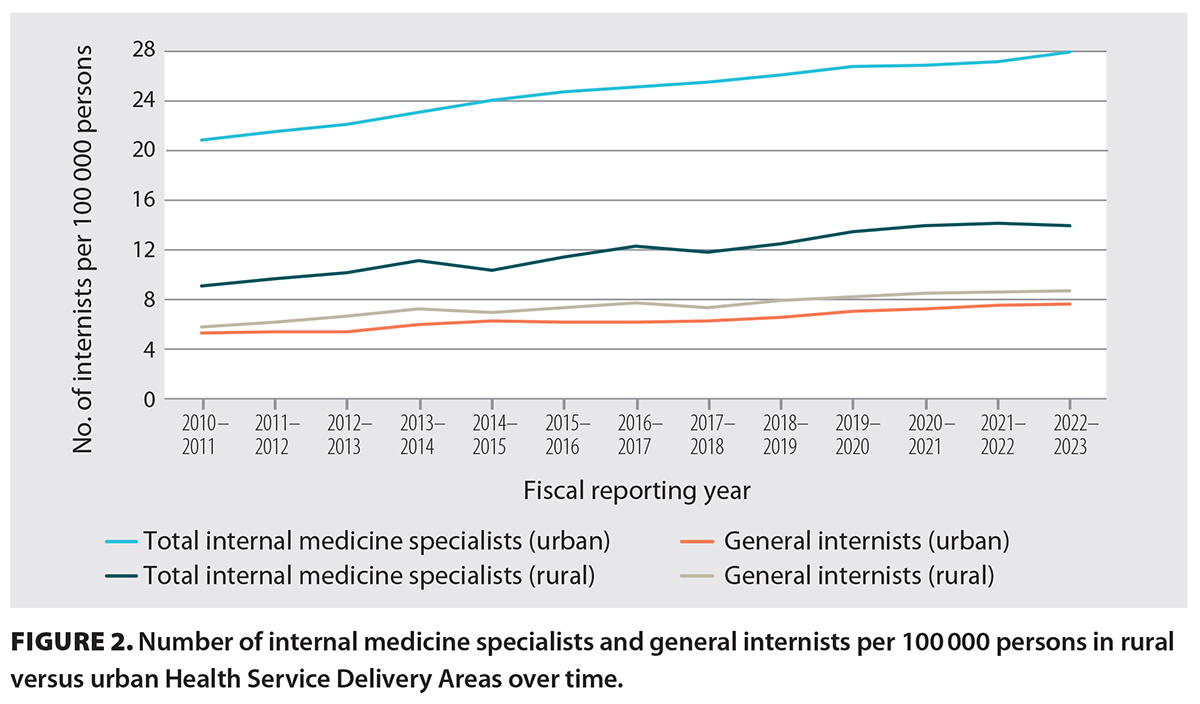

[17]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, the number of general internists per capita increased in both urban and rural regions [Figure 1 [16]; Figure 2 [17]]. In 2022–23, general internists made up a greater proportion of internal medicine specialists in rural regions than in urban centres (100% in the Northeast and Northwest regions versus 25% in Vancouver); similar ratios occurred in 2010–11 [Figure 1 [16]; Supplementary Table 2].

[17]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, the number of general internists per capita increased in both urban and rural regions [Figure 1 [16]; Figure 2 [17]]. In 2022–23, general internists made up a greater proportion of internal medicine specialists in rural regions than in urban centres (100% in the Northeast and Northwest regions versus 25% in Vancouver); similar ratios occurred in 2010–11 [Figure 1 [16]; Supplementary Table 2].

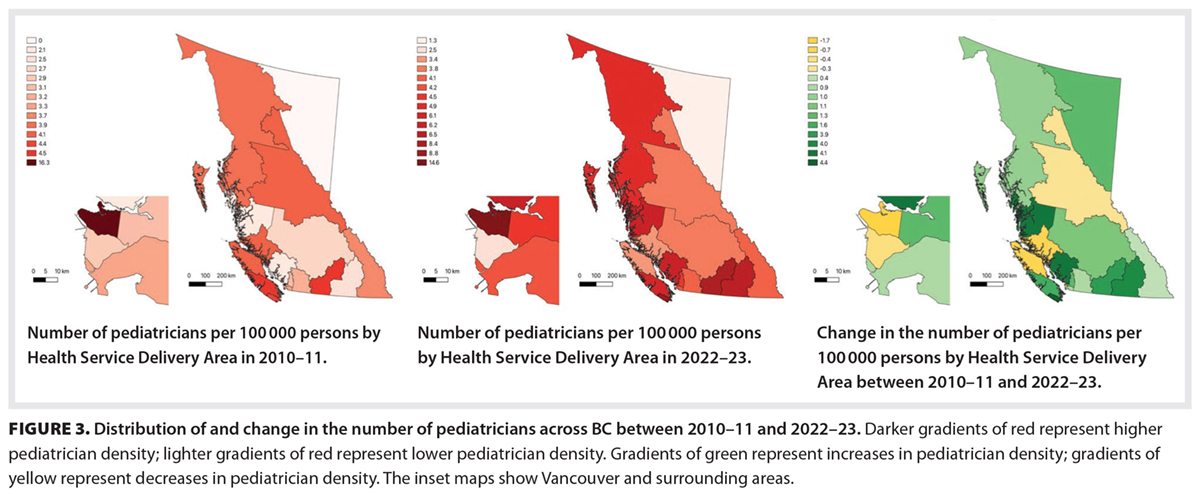

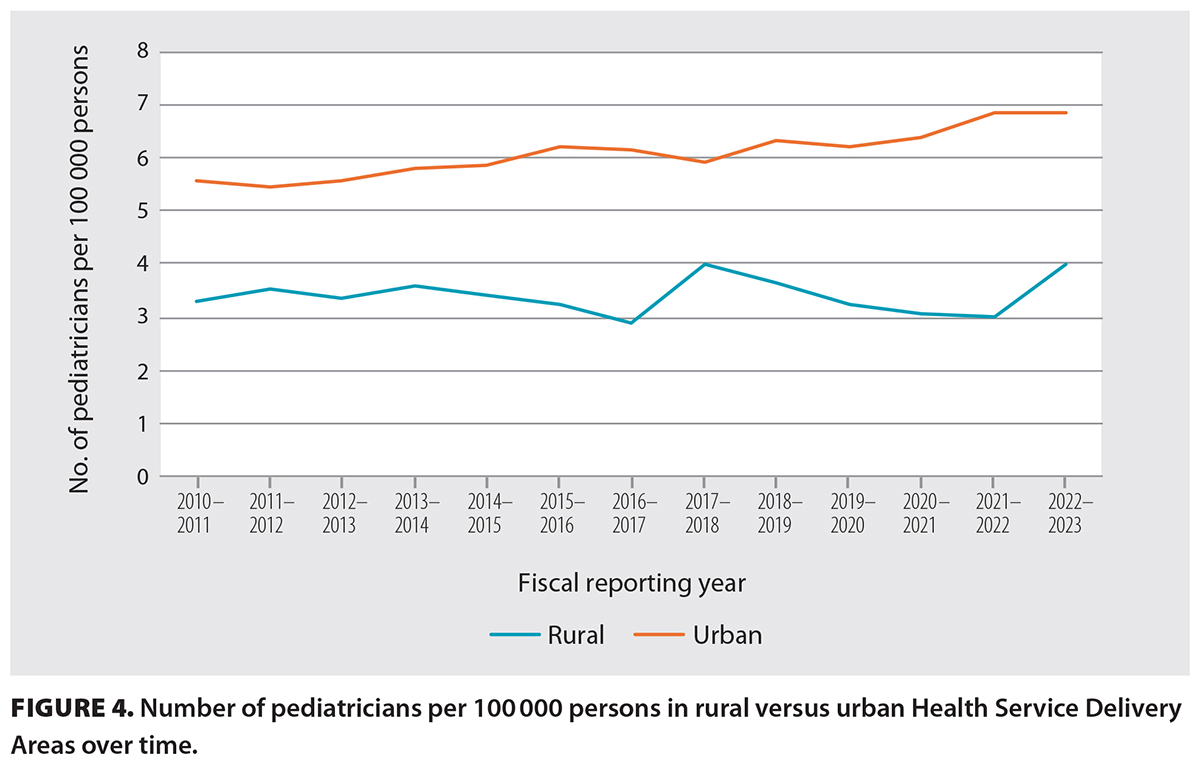

[18]Urban regions had more pediatricians per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1b]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 14.6 pediatricians per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast region had 1.3 pediatricians per 100 000 persons. The provincial median was 4.3 pediatricians per 100 000 persons.

[18]Urban regions had more pediatricians per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1b]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 14.6 pediatricians per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast region had 1.3 pediatricians per 100 000 persons. The provincial median was 4.3 pediatricians per 100 000 persons.

[19]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, there was a mixed trend in the number of pediatricians per capita across regions [Supplementary Table 3; Figure 3 [18]]. In 4 of the 16 HSDAs, the number of pediatricians per capita decreased, including in both rural and urban communities. Urban regions had a slightly greater increase in the number of pediatricians per capita than rural regions [Figure 4 [19]].

[19]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, there was a mixed trend in the number of pediatricians per capita across regions [Supplementary Table 3; Figure 3 [18]]. In 4 of the 16 HSDAs, the number of pediatricians per capita decreased, including in both rural and urban communities. Urban regions had a slightly greater increase in the number of pediatricians per capita than rural regions [Figure 4 [19]].

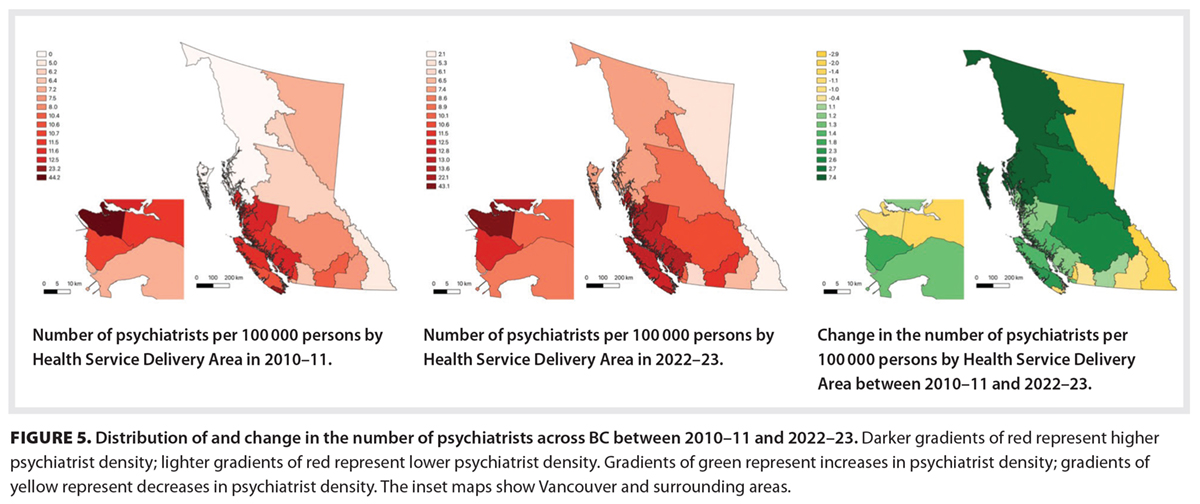

[20]Urban regions had more psychiatrists per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1c; Figure 5 [20]]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 43.1 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast had 5.3 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons. The provincial median was 10.3 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons.

[20]Urban regions had more psychiatrists per capita than rural regions, a situation that has persisted since 2010–11 [Supplementary Table 1c; Figure 5 [20]]. In 2022–23, Vancouver had 43.1 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons, whereas the Northeast had 5.3 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons. The provincial median was 10.3 psychiatrists per 100 000 persons.

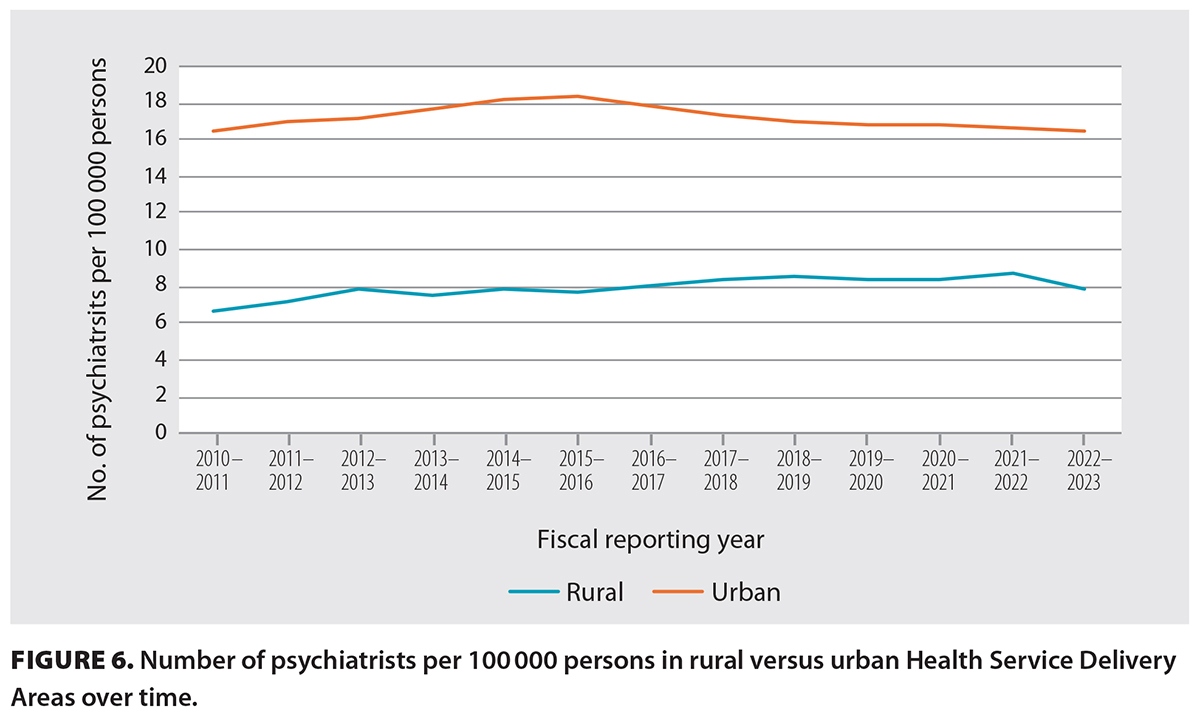

[21]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, there was a mixed trend in the number of psychiatrists per capita across regions [Supplementary Table 3; Figure 6 [21]]. In 7 of the 16 HSDAs, the number of psychiatrists per capita decreased, including in both rural and urban communities. Overall, urban regions experienced no change in the number of psychiatrists per capita, whereas rural regions experienced an increase.

[21]From 2010–11 to 2022–23, there was a mixed trend in the number of psychiatrists per capita across regions [Supplementary Table 3; Figure 6 [21]]. In 7 of the 16 HSDAs, the number of psychiatrists per capita decreased, including in both rural and urban communities. Overall, urban regions experienced no change in the number of psychiatrists per capita, whereas rural regions experienced an increase.

During the study period, there was a disparity in specialist distribution across HSDAs in BC, with fewer specialists per capita in rural regions than in urban centres. This pattern remained constant between 2010–11 and 2022–23, despite absolute increases in the number of specialists. In certain HSDAs, a single specialist may be providing care within their specialty to an entire region; this can pose a serious risk of service disruption to entire geographic regions of BC. The loss of even a single specialist in rural regions can drastically reduce the per capita distribution of specialists in that area. Similarly, small gains in the number of specialists in rural regions translate to significant increases in the number of specialists per capita and access to specialty care. This highlights significant inequities in access to specialist care and the need to create programs that support the recruitment and retention of specialists in rural communities.

In more rural areas, general internists made up a greater proportion of internal medicine specialists than subspecialists, which underscores the importance of rural generalism, a concept that is frequently discussed in primary care literature.[19] General internists have also driven the increase in internal medicine specialists in rural regions that often do not have any subspecialists.

Both urban and rural regions in BC have experienced little change in the number of pediatricians and psychiatrists per capita over time, despite increases in absolute numbers of these specialists. This suggests that the supply and retention of these specialists have not met the demands of population growth. Poor compensation, changing demographics, high call burden, and high rates of physician burnout may be contributing to stagnant availability of pediatricians and psychiatrists.[16,20,21] For psychiatry, simply increasing the number of psychiatrists alone may not be the solution to this complex problem. Rates of use of psychiatry services increase with the number of psychiatrists per capita, but this correlation plateaus in higher-density urban regions.[16] For example, psychiatrists in high-density urban regions in Ontario see fewer patients and are less likely to take on new patients than those in low-density regions.[22] This may be attributed to practitioners seeing the same patients more frequently, working part-time, or focusing on nonclinical duties such as administrative work or research.[16,22]

Further research and policy development are needed to better support the increasing health care needs of rural BC communities where specialists are less readily available than in urban centres. Factors that influence rural physician recruitment and retention include education, remuneration, regulatory environments, organizational support, peer/professional support, lifestyle, and culture.[5,23,24] Efforts can be made to facilitate social engagement between rural community members and newly recruited rural specialists and their families.[23] Social support should be provided to specialists and their families to ensure their seamless integration into rural communities, especially for clinicians who are new to providing care in Canada. Specialists should be supported in their transition to rural practice through mentorship programs; team building; facilitative organizational factors; and opportunities for upskilling, networking, and career progression.[24]

The University of British Columbia has made efforts to address gaps in rural education by opening its Northern, Interior, and Vancouver Island campuses. Graduates from these campuses are more likely to enter family practice and ultimately to practise in rural communities, particularly if they have a rural background.[4] However, additional efforts are needed to ensure that postgraduate specialty programs are also selecting residents who are interested in serving rural communities and that they are optimally trained for rural practice.[1,4] There is a need for increased postgraduate specialty training opportunities in rural settings, for both residents with an interest in rural practice and those who intend to work in urban centres that will provide tertiary care for rural patients.[4,23] Increasing rural content in medical school and postgraduate curricula, along with rural specialist mentorship programs for interested trainees, may enhance rural specialist recruitment.[23]

The BC Ministry of Health is also working to improve access to rural specialists through various programs, including by providing financial incentives, supporting outreach visits, facilitating locum doctors, and providing rural educational opportunities.[5,25] Streamlining hospital privileging processes and cross-national licensing are also needed to ensure safe and effective rural specialist practice.[26] Current MSP billing codes support easy access to virtual care. While virtual care has significantly reduced barriers to providing health care to remote and rural communities, it remains an adjunct to in-person consultations. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC states that “the appropriate use of virtual care includes access to in-person care and is ultimately a professional decision of the registrant made in conjunction with their patients.”[27] Virtual care cannot replace the connectivity and trust that an in-person consultation provides, especially for vulnerable patient populations or for the understanding of community context, values, and resources that comes from spending time in rural communities. Virtual care does not provide clinicians with information gained from a thorough physical examination or the ability to assess body language and behavior. Basic medical services such as emergency care and routine measurements (e.g., blood pressure, pediatric growth assessments) are also difficult to support virtually without the added assistance of nursing staff. Additionally, virtual care faces technological limitations related to network connectivity and hardware availability in rural areas, digital literacy of patients and staff, and privacy concerns regarding the use of digital platforms.[28] While exclusive virtual care may be appropriate in specific cases, other situations require in-person assessment or live support from ancillary staff. Virtual care is an important tool in reducing health care barriers in rural settings, but further research and policy guidance are needed to inform the most appropriate balance between in-person and virtual care.

Rural specialists are also improving rural access to specialty care by creating organizations such as the General Rural Internal Medicine (GRIM) and Sustaining Pediatrics in Rural and Underserved Communities (SPRUCe) networks.[8,29] These organizations aim to identify areas of need in rural communities, connect rural communities with locums or visiting specialists, and facilitate interprovider communication between specialist teams in rural and urban communities. They also advocate for rural medicine through providing support and mentorship to learners and clinicians interested in rural medicine.

Rural health care disparities are complex, and multifaceted solutions are essential to ensure all Canadians can access high-quality medical services. Innovative solutions, investments in rural health infrastructure, and increased recruitment and retention of specialists are needed to ensure equitable access to specialist care for rural populations.[13,16]

This study included only internal medicine, pediatrics, and psychiatry; therefore, the findings do not necessarily reflect the distribution of other specialties, including surgical specialties. The data do not account for services provided via telehealth, locum physicians, and visiting outreach models, which are strategies to address the health care gaps in rural BC. The data also do not capture exclusively salaried physicians or types of service, practice setting, hours worked, or volume of patients seen, all of which may affect access to specialist care. The pediatrician data were based on general pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists using MSP pediatric fee codes. Pediatrician and psychiatrist subspecialists were not accounted for separately, which resulted in a knowledge gap in rural access to these disciplines. Additionally, MSP population data were not age adjusted, so both pediatric and adult populations were included.

Overall, we found rural–urban discrepancies in specialist distribution in BC, which have persisted over the past decade. We call upon clinicians and policymakers to address this long-standing issue.

Dr Jaworsky received research funding from Health Research BC.

Dr Jaworsky and Dr Warbrick are co-leads of the GRIM network. Dr Miller and Dr Retallack are co-leads of the SPRUCe network. Dr Jaworsky is a member of the BCMJ Editorial Board but was not involved in the review and publication decision process for this article.

This article has been peer reviewed.

[22] [22] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [22]. |

1. Snadden D, Casiro O. Maldistribution of physicians in BC: What we are trying to do about it. BCMJ 2008;50:371-372.

2. Wilson G, Kelly A, Thommasen HV. Training physicians for rural and northern British Columbia. BCMJ 2005;47:373-376.

3. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Supply, distribution and migration of physicians in Canada, 2022 – data tables. Ottawa, ON; 2022.

4. Lovato CY, Hsu HCH, Bates J, et al. The regional medical campus model and rural family medicine practice in British Columbia: A retrospective longitudinal cohort study. CMAJ Open 2019;7:E415-E420. https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20180205 [23].

5. McKay M, Lavergne MR, Lea AP, et al. Government policies targeting primary care physician practice from 1998-2018 in three Canadian provinces: A jurisdictional scan. Health Policy 2022;126:565-575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.006 [24].

6. Naik H, Murray TM, Khan M, et al. Population-based trends in complexity of hospital inpatients. JAMA Intern Med 2024;184:183-192. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7410 [25].

7. Health Match BC. Find a job. Accessed 25 August 2025. https://applicants.healthmatchbc.org/JobsBoard/HMBC/Default.aspx [26].

8. Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. Sustaining pediatrics in rural & underserved communities. Accessed 23 August 2025. https://rccbc.ca/initiatives/spruce/ [27].

9. Caxaj CS. A review of mental health approaches for rural communities: Complexities and opportunities in the Canadian context. Can J Commun Ment Health 2016;35:29-45. https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2015-023 [28].

10. Edwards A, Hung R, Levin JB, et al. Health disparities among rural individuals with mental health conditions: A systematic literature review. Rural Ment Health 2023;47:163-178. https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000228 [29].

11. Maddess RJ. Mental health care in rural British Columbia. BCMJ 2006;48:172-173.

12. Lowe L, Fearon D, Adenwala A, Harris DW. The state of mental health in Canada 2024: Mapping the landscape of mental health, addictions and substance use health. Toronto, ON: Canadian Mental Health Association; 2024. Accessed 13 November 2025. https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/CMHA-State-of-Mental-Health-2024-report.pdf [30].

13. Anish N, Minnabarriet H, Hawe N, et al. Navigating the odyssey: The challenges of medical travel for people living in rural and remote communities in Canada—A narrative review. CJGIM 2025;20:162-185. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjgim.2025.0003 [31].

14. Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. Real-time virtual support. Accessed 23 August 2025. https://rccbc.ca/initiatives/rtvs/ [32].

15. Duke S, Treissman J, Freeman S, et al. A mixed-methods exploration of the Real-Time Virtual Support pathway Child Health Advice in Real-Time Electronically in Northwestern BC. Paediatr Child Health 2024;29:346-353. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxae063 [33].

16. Rudoler D, Kaoser R, Lavergne MR, et al. Regional variation in supply and use of psychiatric services in 3 Canadian provinces: Variation régionale de l’offre de services psychiatriques et de leur utilisation dans trois provinces canadiennes. Can J Psychiatry 2025;70:511-523. https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437251322404 [34].

17. British Columbia Ministry of Health, Health Sector Information, Analysis and Reporting Division. MSP information resource manual fee-for-service payment statistics. Last updated 3 November 2023. Accessed 13 November 2025. www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/PubDocs/bcdocs/340499/ [35].

18. Government of British Columbia, Association of Doctors of BC, Medical Services Commission. 2022 rural practice subsidiary agreement. 1 April 2022. Accessed 13 November 2025. www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/appendix_c_rural_subsidiary_agreement.pdf [36].

19. Schubert N, Evans R, Battye K, et al. International approaches to rural generalist medicine: A scoping review. Hum Resour Health 2018;16:62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0332-6 [37].

20. Vinci RJ. The pediatric workforce: Recent data trends, questions, and challenges for the future. Pediatrics 2021;147:e2020013292. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-013292 [38].

21. Miller K, Ward V. Understanding the paediatric workforce in British Columbia: A survey of BC paediatricians. Paediatr Child Health 2022;27(Suppl 3):e5-e6. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxac100.013 [39].

22. Kurdyak P, Stukel TA, Goldbloom D, et al. Universal coverage without universal access: A study of psychiatrist supply and practice patterns in Ontario. Open Med 2014;8:e87-e99.

23. Lee DM, Nichols T. Physician recruitment and retention in rural and underserved areas. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2014;27:642-652. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhcqa-04-2014-0042 [40].

24. Wieland L, Ayton J, Abernethy G. Retention of general practitioners in remote areas of Canada and Australia: A meta-aggregation of qualitative research. Aust J Rural Health 2021;29:656-669. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12762 [41].

25. Government of British Columbia. Rural practice programs. Last updated 19 March 2025. Accessed 20 July 2025. www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/physician-compensation/rural-practice-programs [42].

26. Kornelsen J, Cameron A, Rutherford M, et al. The provincial privileging process in British Columbia through a rural lens. BCMJ 2024;66:334-339.

27. College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. Virtual care. Practice standard. Last updated 22 June 2023. Accessed 15 October 2025. www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/PSG-Virtual-Care.pdf [43].

28. Kruse CS, Williams K, Bohls J, Shamsi W. Telemedicine and health policy: A systematic review. Health Policy Technol 2021;10:209-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.10.006 [44].

29. Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia. General rural internal medicine. Accessed 23 August 2025. https://rccbc.ca/annual-report/2024-annual-report/general-rural-internal-medicine/ [45].

Dr Nadeem is a graduate of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. Dr Hehar is a graduate of the Faculty of Medicine, University of British Columbia, and a pediatric resident at the University of Saskatchewan. Dr Ayub is a resident in the Faculty of Medicine, UBC. Dr Miller is a clinical assistant professor in the Faculty of Medicine, UBC; a co-lead of Sustaining Pediatrics in Rural and Underserved Communities (SPRUCe) at the Rural Coordination Centre of British Columbia (RCCbc); and a pediatrician at University Hospital of Northern British Columbia. Dr Retallack is a clinical assistant professor in the Faculty of Medicine, UBC, and a co-lead of SPRUCe at RCCbc. Dr Warbrick is a clinical instructor in the Faculty of Medicine, UBC, and a co-lead of general rural internal medicine at RCCbc. Dr Jaworsky is a clinical associate professor in the Faculty of Medicine, UBC; a physician partner at RCCbc; and a general internal medicine specialist at East Kootenay Regional Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Denise Jaworsky, denise.jaworsky@ubc.ca [46].

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/node/11060

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/zohaib-nadeem-md

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/harleen-hehar-md

[4] https://bcmj.org/author/aysha-ayub-md

[5] https://bcmj.org/author/kirsten-miller-md-frcpc

[6] https://bcmj.org/author/jenny-retallack-md-frcpc

[7] https://bcmj.org/author/ian-warbrick-md-frcpc

[8] https://bcmj.org/author/denise-jaworsky-md-phd-frcpc

[9] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_Regional%20disparities-in-medical-specialties.pdf

[10] https://bcmj.org/print/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia

[11] https://bcmj.org/printmail/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia

[12] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[13] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Regional disparities in medical specialties in rural British Columbia&url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[14] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[15] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[16] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_Regional%20disparities-in-medical-specialties_Figure1.jpg

[17] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_Regional-disparities-in-medical-specialties_Figure2.jpg

[18] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_core-regional-disparities_Figure3.jpg

[19] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_Regional-disparities-in-medical-specialties_Figure4.jpg

[20] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_core-regional-disparities_Figure5.jpg

[21] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No1_Regional-disparities-in-medical-specialties_Figure6.jpg

[22] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[23] https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20180205

[24] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.006

[25] https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2023.7410

[26] https://applicants.healthmatchbc.org/JobsBoard/HMBC/Default.aspx

[27] https://rccbc.ca/initiatives/spruce/

[28] https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2015-023

[29] https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000228

[30] https://cmha.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/CMHA-State-of-Mental-Health-2024-report.pdf

[31] https://doi.org/10.3138/cjgim.2025.0003

[32] https://rccbc.ca/initiatives/rtvs/

[33] https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxae063

[34] https://doi.org/10.1177/07067437251322404

[35] http://www.llbc.leg.bc.ca/public/PubDocs/bcdocs/340499/

[36] http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/practitioner-pro/appendix_c_rural_subsidiary_agreement.pdf

[37] https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-018-0332-6

[38] https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-013292

[39] https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxac100.013

[40] https://doi.org/10.1108/ijhcqa-04-2014-0042

[41] https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12762

[42] http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/health/practitioner-professional-resources/physician-compensation/rural-practice-programs

[43] http://www.cpsbc.ca/files/pdf/PSG-Virtual-Care.pdf

[44] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.10.006

[45] https://rccbc.ca/annual-report/2024-annual-report/general-rural-internal-medicine/

[46] mailto:denise.jaworsky@ubc.ca

[47] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176?arturl=/articles/regional-disparities-medical-specialties-rural-british-columbia&nodeid=67

[48] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop