ABSTRACT: Gastroesophageal reflux disease is one of the most common upper-gastrointestinal disorders and accounts for considerable symptom burden and health care use. If left untreated, it can lead to complications such as esophagitis, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma. However, most patients can be managed in primary care using a structured approach. The disease is generally diagnosed clinically; in patients with typical symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation without alarm features, an empiric trial of proton pump inhibitors serves as first-line therapy. Diagnostic endoscopy is reserved for those with alarm features, inadequate response to optimized therapy, or risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Patients with persistent or atypical symptoms despite optimized therapy warrant further evaluation, such as upper endoscopy and esophageal function testing, including esophageal manometry and pH testing. Antireflux surgery may be considered in carefully selected patients, and laparoscopic fundoplication can offer relief in selected patients. Newer options such as magnetic sphincter augmentation and endoscopic techniques have limited roles.

Most patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease can achieve excellent outcomes in a primary care setting if given a history-based diagnosis and appropriate pharmacological therapy, lifestyle counseling, and follow-up.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders affecting Canadians; it impacts up to 1 in 5 adults and is responsible for a large proportion of primary care visits.[1] Its symptoms, often dismissed as benign heartburn or indigestion, can erode quality of life; disrupt sleep; and lead to complications such as esophagitis, strictures, Barrett’s esophagus, and esophageal adenocarcinoma if left untreated. Given its high prevalence, GERD is a condition that primary care providers are uniquely positioned to manage effectively. With a thoughtful approach that emphasizes history-based diagnosis, rational use of pharmacological management, lifestyle counseling, and appropriate follow-up, most patients can achieve excellent outcomes in a primary care setting without specialist referral. This article provides an evidence-based approach for primary care clinicians to navigate GERD confidently and helps them recognize when reassurance and education suffice and when escalation or further investigation by a gastroenterologist is warranted.

Aarti, a 38-year-old woman, reports a 2-year history of heartburn one to two times per week, often after eating spicy food or late-evening meals. She takes 20 mg of omeprazole as needed with meals, when symptomatic. She finds some relief, but symptoms continue to recur. She has no dysphagia, weight loss, anemia, or alarm features [Box]. She prefers to avoid daily medication if possible. How would you manage Aarti’s current symptoms and proton pump inhibitor use?

BOX. Alarm features in GERD.

The following symptoms are rare in GERD and warrant further investigation:

David, a 46-year-old man, has had daily heartburn for years. He has a 50-pack-year history of smoking. His BMI is 31. He has been on 40 mg of esomeprazole twice daily for 6 weeks, with minimal improvement. He reports no dysphagia, odynophagia, weight loss, or gastrointestinal bleeding. What are the next steps in his management, and does he need an upper endoscopy?

The Montreal Consensus defines GERD as a multifactorial condition in which gastric contents reflux into the esophagus, causing troublesome symptoms and/or complications.[2] The esophagogastric junction, comprising the lower esophageal sphincter and crural diaphragm, normally prevents reflux, but it can be compromised by transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations; low basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure; or anatomical defect, such as hiatal hernia.[3] Acid and bile exposure can trigger mucosal injury via inflammatory mediators.[3] Impaired clearance from upper gastrointestinal dysmotility or xerostomia, as in Sjögren’s syndrome, may prolong refluxate contact time. Symptom severity varies with mucosal sensitivity and may not correlate with acid exposure.[3]

Chronic acid and bile reflux can erode the esophageal squamous epithelium, leading to inflammation and ulceration (reflux esophagitis).[3-5] Repeated injury and subsequent fibrosis during the healing process can cause stricture formation and significant dysphagia. This cycle of injury and healing in the distal esophageal squamous lining can cause progenitor cells at the gastroesophageal junction to accumulate somatic mutations and reprogram themselves, forming metaplastic columnar epithelium, which is more resistant to acid.[6,7] This specialized intestinal metaplasia, known as Barrett’s esophagus, represents a premalignant condition in approximately 1% to 2% of the general population and up to 10% to 15% of patients with chronic GERD.[6] Barrett’s esophagus progresses along a metaplasia–dysplasia–carcinoma sequence, from non-dysplastic metaplasia to low-grade dysplasia, high-grade dysplasia, and eventually invasive esophageal adenocarcinoma.[6,7] Although the annual risk of progression to cancer in nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is low (approximately 0.5% per year), the high prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the population makes it the predominant precursor lesion for esophageal adenocarcinoma, with most cases arising through this metaplastic–dysplastic pathway.[7]

Typical GERD symptoms include heartburn (substernal burning toward the throat); regurgitation of sour/bitter contents; and chest pain, which can mimic cardiac pain.[5] Regurgitation should be distinguished from rumination, in which involuntary abdominal contractions cause the return of recently ingested food. The latter usually occurs while eating or shortly after eating, where the content tastes similar to the material just ingested; the content is often chewed again and swallowed back down.[5]

The Lyon Consensus, an expert statement that provides objective diagnostic thresholds for GERD, also describes gastric belching, a physiologic venting of air that may precipitate reflux, and supra-gastric belching, a behavioral pattern of rapid air entry/expulsion before entry into the stomach.[5] Differentiating these symptoms is important in patients who are thought to have proton pump inhibitor–refractory GERD, in which case their esophageal symptoms are persistent despite good compliance with a course of single- or double-dose proton pump inhibitor, taken 30 minutes before a meal, for 4 to 8 weeks.

Patients may report cough, hoarseness, throat clearing, globus sensation, asthma-like symptoms, nausea, and/or abdominal pain.[5,6] In the absence of typical reflux symptoms, these have low sensitivity and specificity for GERD in isolation, and acid suppression is often ineffective.[6] Chronic cough usually has multiple causes, including upper airway cough syndrome, postinfectious respiratory diseases, postnasal drip, environmental exposures, ACE inhibitors, nonacid reflux, irritable larynx syndrome, and other cardiopulmonary pathologies. In addition, placebo response to proton pump inhibitors in this patient population can be high, with up to 42% of patients in placebo groups in randomized trials reporting adequate relief of laryngeal or cough symptoms.[8] When cough or laryngitis occurs without typical GERD symptoms, objective reflux testing (pH with impedance monitoring) off proton pump inhibitor therapy should precede antacid therapy.[5] Globus hystericus is more often linked to visceral hypersensitivity and hypervigilance and often responds better to neuromodulators, such as low-dose tricyclic antidepressants.[6] If atypical symptoms accompany typical GERD symptoms in the absence of alarm features, an up-front 8- to 12-week proton pump inhibitor trial is reasonable; nonresponders should be referred for objective reflux monitoring.[5]

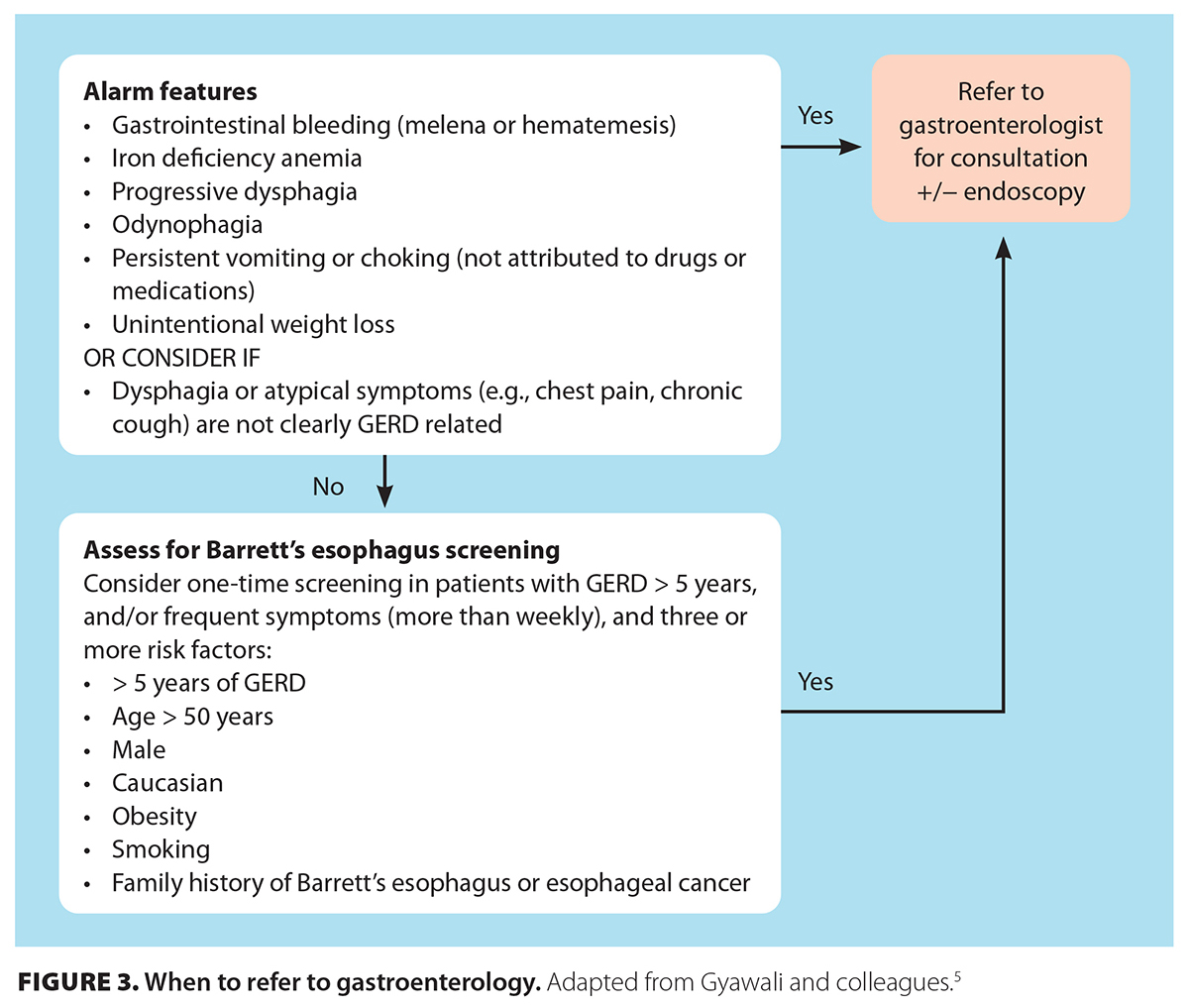

Alarm features—dysphagia, odynophagia, gastrointestinal bleeding or anemia, weight loss, recurrent vomiting, or choking—are uncommon in GERD and warrant further investigation, including early upper endoscopy.[4] Without alarm features, a 4- to 8-week proton pump inhibitor trial is diagnostic of GERD if symptoms resolve. Partial relief may justify twice-daily dosing for another 4 to 8 weeks. No response should prompt further investigation.[4] In resource-rich settings, up-front esophageal pH monitoring off proton pump inhibitor therapy is suggested for atypical presentations or proton pump inhibitor nonresponse before long-term therapy or invasive management is initiated.[4,5] Generally, an upper endoscopy is indicated before any esophageal function testing, which allows objective evaluation for alternative diagnoses, such as esophageal dysmotility, functional heartburn, or esophageal hypersensitivity.

Up-front upper endoscopy is recommended for patients with alarm features or Barrett’s esophagus risk factors: older than 50 years of age, male sex, central obesity, Caucasian race, tobacco use, GERD for 5 years or longer, or a family history of Barrett’s esophagus or adenocarcinoma.[4]

The Los Angeles classification grades endoscopic appearance of erosive esophagitis from A (≤ 5 mm mucosal breaks not bridging folds) to D (≥ 75% circumferential injury) [Figure 1 [11]].[9] Objective endoscopic evidence of GERD includes the presence of grade B, C, or D esophagitis; Barrett’s esophagus; peptic stricture; or previous abnormal pH monitoring off proton pump inhibitor therapy.[5] The yield of initial upper endoscopy for GERD can increase with discontinuing proton pump inhibitor therapy for 2 to 4 weeks.[4] The absence of visible esophageal mucosal injury on endoscopy may suggest nonerosive GERD and represents most GERD cases. If clinically relevant, it can be followed up with pH testing to objectively document the presence of pathologic GERD[4,5]—for example, in cases of proton pump inhibitor non-responders. However, given the limited access to esophageal function testing, judicious use of resources should be considered.

Barrett’s esophagus—salmon-colored, velvety mucosa with histologic intestinal metaplasia—confirms GERD and requires surveillance.[4] Barrett’s esophagus is graded endoscopically using the Prague C&M Classification (outlining the circumferential extent and maximal length of involved tissue) and requires careful 4-quadrant biopsies every 1 to 2 cm per the Seattle Protocol, with specific care to target suspicious-appearing lesions.[10] Endoscopic surveillance intervals depend on the presence of dysplasia. When there is no dysplasia, upper endoscopy is recommended in 3 to 5 years; if it is indefinite for dysplasia after review by two dedicated gastrointestinal pathologists, a repeat endoscopy should be done in 6 to 12 months after adequate acid suppression.[10] Preferably, low-grade dysplasia should be referred for endoscopic eradication (otherwise, surveillance should be conducted every 6 to 12 months).[10] Visible high-grade dysplasia or intramucosal carcinoma must be endoscopically resected, with close endoscopic follow-up at 3, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter.[10]

The updated Lyon Consensus defines “actionable GERD” as Los Angeles grade B, C, or D esophagitis; long-segment Barrett’s esophagus (longer than 3 cm); peptic stricture; more than 80 reflux episodes; or distal esophageal acid exposure time greater than 6% on a 24-hour catheter-based study.[5] Further details of these investigations are outside the scope of this article. Overall, this physiologic framework helps direct therapy and avoid overtreatment, especially with prolonged proton pump inhibitor use in functional heartburn or reflux hypersensitivity.

Ambulatory esophageal pH or pH-impedance monitoring is the gold standard for confirming conclusive pathologic GERD, defined as distal esophageal acid exposure time greater than 6% or more than 80 reflux episodes over 24 hours off proton pump inhibitor therapy.[4,5] Testing is indicated when diagnostic uncertainty exists; when there is incomplete proton pump inhibitor response; and before antireflux surgery in patients with typical GERD symptoms who have minimal or no endoscopic findings, yet symptoms persist despite optimal use of proton pump inhibitors.[4] In a resource-rich region where access to esophageal function testing is readily available, patients with atypical reflux symptoms, such as cough, sore throat, or globus, with no heartburn or acid regurgitation, should undergo up-front esophageal manometry and pH testing off proton pump inhibitors.

Catheter-based impedance–pH monitoring detects acidic and nonacidic reflux and allows the correlation of reflux episodes with reported symptoms.[4] Another modality includes wireless capsule monitoring (Bravo test), implanted in the distal esophagus during upper endoscopy, which allows recording of distal acid exposure time up to 96 hours. Barium swallow is not recommended solely for reflux diagnosis, because reflux seen on esophagram is not diagnostic of pathologic GERD.[4]

Currently, the motility lab at Vancouver General Hospital serves as the centre for excellence in BC; it accepts referrals for patients with gastrointestinal motility disorders throughout the province, while offering evidence-based, up-to-date reporting of esophageal function testing, based on rapidly evolving literature. The lab is also involved in research on esophageal disorders, including esinophilic esophagitis and esophageal motility disorders. However, resources remain limited; therefore, patients are reviewed and accepted from specialty services based on stringent criteria, outlined on the BC centralized referral form.

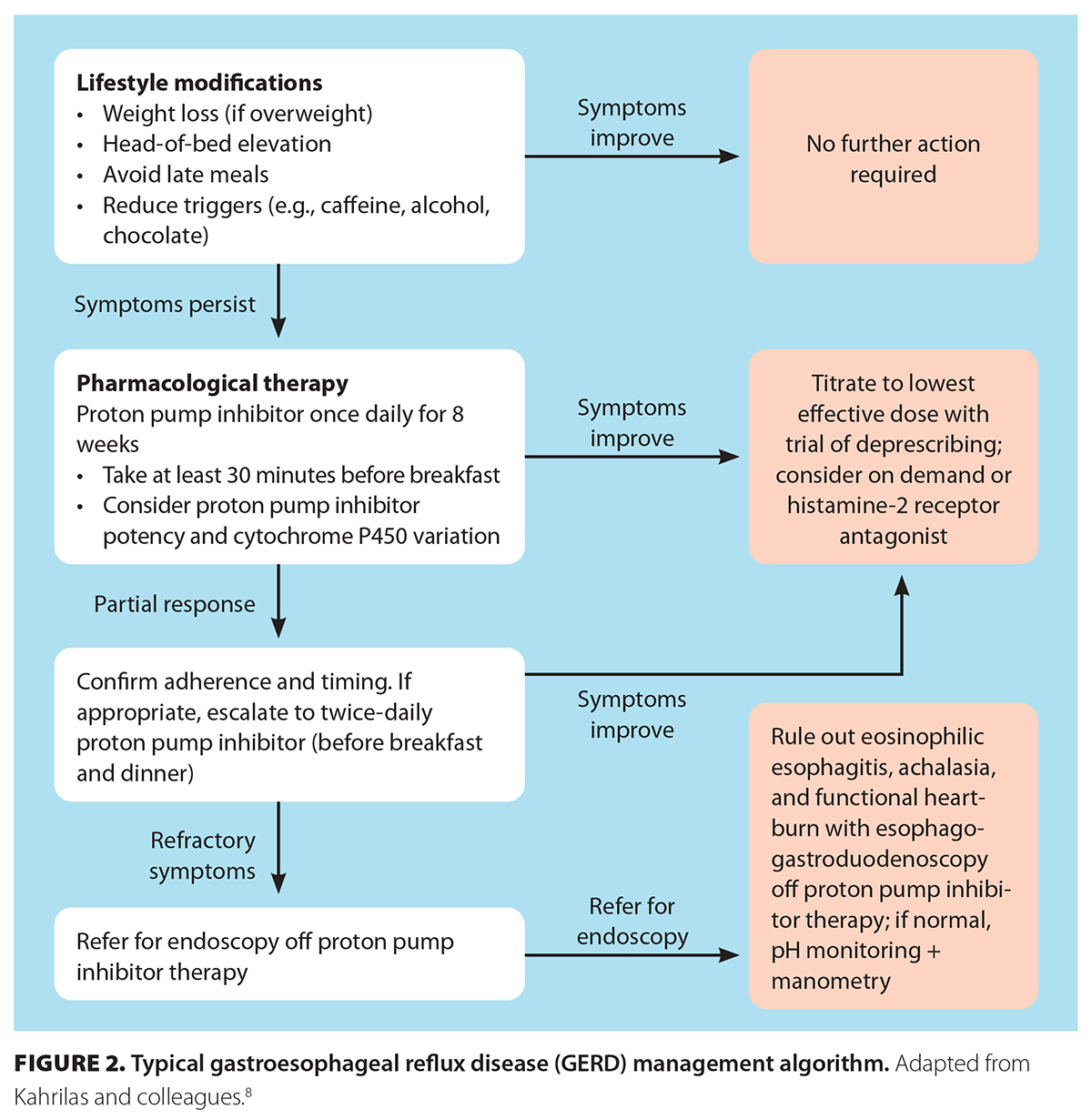

Adjunctive lifestyle changes are recommended, although evidence of their benefits is modest. Even moderate weight loss in overweight patients consistently improves symptoms.[4,11] Other measures include elevating the head of the bed, particularly for nocturnal symptoms; avoiding recumbency after meals for 4 hours; and limiting late-night eating or snacking.[4,11] Smoking cessation and reduced alcohol intake are advised, because both smoking and alcohol impair lower esophageal sphincter function.[3,4] Trigger-food avoidance is reasonable when individualized; common culprits include caffeine, chocolate, peppermint, spicy foods, citrus, and fatty meals.[4] Lifestyle measures may reduce symptoms but rarely replace pharmacologic therapy in severe reflux.

Proton pump inhibitors are first-line therapy for reflux esophagitis and are superior to H2 blockers for symptom control and mucosal healing.[4,5] Standard dosing is once daily, 30 minutes before breakfast, with improvement expected in 4 to 8 weeks; erosive esophagitis usually requires 8 weeks or longer, with more than 80% healing.[4] Severe esophagitis (Los Angeles C or D) or Barrett’s esophagus may warrant higher-dose therapy (twice a day or double strength),[5] with indefinite use likely required to avoid recurrence and risk of further progression of Barrett’s dysplasia to esophageal cancer.[10,12,13]

Beyond symptom control, proton pump inhibitors may provide chemopreventive benefit in Barrett’s esophagus. Observational studies and meta-analyses suggest that long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with a reduced risk of neoplastic progression, likely through sustained acid suppression and reduction of inflammation-mediated DNA injury.[12] The AspECT trial indicated that high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy (40 mg of esomeprazole twice daily), particularly when combined with aspirin (300 to 325 mg daily), significantly prolonged the time to the composite endpoint of high-grade dysplasia, esophageal adenocarcinoma, or death, compared with standard-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy alone.[13] However, routine use of high-dose aspirin for chemoprevention is not recommended in current gastrointestinal practice due to bleeding risk in patients without another clear indication for chronic antiplatelet therapy.[14]

Patients metabolize CYP2C19 at varying rates, so their GERD response can vary depending on the proton pump inhibitor used. First-generation proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole) are more affected by rapid-metabolizer phenotypes; in non-responders, switching to second-generation proton pump inhibitors (e.g., rabeprazole, esomeprazole, dexlansoprazole) that are less influenced by CYP2C19 metabolism polymorphism should be considered if their higher cost is acceptable to the patient.[15]

Clinically important adverse effects from chronic proton pump inhibitors are rare, and in high-quality randomized, placebo-controlled studies conducted over multiple years, they were generally not statistically different from placebo; a small excess of enteric infections may occur.[16] In meta-analyses, proton pump inhibitors have been linked to Clostridioides difficile infection, but effect sizes are modest (typical pooled odds ratio ~1.3 to 2.3 [i.e., < 3]) and subject to confounding.[16,17]

H2 blockers can relieve mild or breakthrough symptoms, but they are less effective than proton pump inhibitors in healing erosive esophagitis and are prone to tachyphylaxis.[5] A notable side effect is gynecomastia, particularly with cimetidine.[18]

Alginates form a “raft” barrier, are safe in pregnancy, and are useful as adjuncts in partial proton pump inhibitor responders or those with nonacid reflux.[19] Baclofen reduces transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations but is limited by CNS effects.[4] Antacids provide only short-term relief by neutralizing acid and require caution and monitoring in patients with renal impairment.[20] Prokinetics (e.g., metoclopramide, domperidone) are reserved for coexisting gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia.[14] For metoclopramide, Food and Drug Administration labeling limits use to a maximum of 12 weeks due to tardive dyskinesia risk and advises caution for QT prolongation and arrhythmia risk; RCT and observational data show effects on QT dynamics.[21,22] The same potential cardiac side effect may be seen with domperidone.[22]

Vonoprazan (a potassium-competitive acid blocker) is Food and Drug Administration approved in the United States for Helicobacter pylori eradication (dual/triple packs) and for erosive GERD/maintenance; currently, the class is not approved in Canada.[23,24]

Once symptoms are controlled, we recommend stepping down proton pump inhibitors to the lowest effective dose. If GERD symptoms are under control, consideration can be given to using proton pump inhibitors on demand, or intermittently in nonerosive reflux disease. Severe esophagitis or chronic symptoms may require long-term therapy and reassessment on a case-by-case basis [Table [12]].

If symptoms persist, first confirm adherence to, dosing of, and timing of proton pump inhibitor therapy, which should be 30 to 60 minutes pre-meal dosing. True refractory GERD—persistent symptoms despite twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy for 4 to 8 weeks—requires objective testing: upper endoscopy followed by esophageal manometry and pH-impedance off proton pump inhibitor if esophagogastroduodenoscopy shows no abnormalities.[5] This is to distinguish esophageal dysmotility and pathologic reflux from esophageal hypersensitivity or functional heartburn, where the latter often responds better to neuromodulators such as low-dose tricyclic antidepressants.[4] In patients who remain symptomatic despite optimized therapy, CYP2C19 genetic variability should be considered. Rapid and ultrarapid metabolizers can demonstrate increased hepatic clearance and subtherapeutic acid suppression; switching to proton pump inhibitors that are less affected by CYP2C19 metabolism (e.g., esomeprazole, rabeprazole, dexlansoprazole) can improve response.[17] In proven GERD with good symptom association on pH testing that is partially or totally unresponsive to optimized pharmacologic and dietary therapies, anti-reflux surgery may be considered in carefully selected patients. Laparoscopic fundoplication offers durable relief in selected patients (e.g., young patients with severe erosive disease or large hiatal hernia),[4] although 30% to 40% resume the use of proton pump inhibitors and 4% to 10% require reoperation for complications such as gas bloat, dysphagia, or wrap failure within a few years after surgery.[4,14] Newer options—magnetic sphincter augmentation and endoscopic techniques (e.g., transoral incisionless fundoplication, Stretta)—have limited roles, and should preferably be considered in expert centres.[4] Careful selection and physiologic testing are essential in ensuring a successful outcome.

Aarti has uncomplicated GERD with no alarm features. However, her proton pump inhibitor use can be further optimized by taking the proton pump inhibitor 30 to 60 minutes before a meal for a 4- to 8-week trial. If effective, she can switch to antireflux medications as needed, if symptoms recur. She should be counseled on adjunctive lifestyle measures, as discussed above [Figure 2 [13]].

David has proton pump inhibitor–refractory GERD, defined as persistent typical symptoms of GERD, despite optimized twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy for 4 to 8 weeks. He should be referred for consideration of upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsies, ideally off proton pump inhibitor therapy for 2 to 4 weeks to increase the yield of biopsies [Figure 3 [14]]. Endoscopic evaluation will allow clinicians to rule out mimickers such as eosinophilic esophagitis or peptic ulcer disease. If there are no abnormalities, esophageal manometry may be indicated to assess esophageal motility disorders, followed by ambulatory pH or impedance–pH monitoring off proton pump inhibitor therapy to differentiate pathologic GERD from esophageal hypersensitivity or functional heartburn. Proton pump inhibitor doses should not be taken more than twice a day; adjuncts such as baclofen, alginates, or neuromodulators may be considered after testing.

[13] [13] |

[14] [14] |

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a prevalent and often chronic condition that can be effectively managed in the primary care setting using a structured, evidence-based approach. Most patients achieve symptom control through accurate clinical diagnosis, lifestyle modification, and rational use of proton pump inhibitors. Primary care physicians play a pivotal role in early recognition, appropriate empiric therapy, and patient education to prevent complications such as erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus. Diagnostic endoscopy should be reserved for those with alarm features, inadequate response to optimized therapy, or risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Patients with persistent or atypical symptoms despite optimized therapy warrant further evaluation, such as upper endoscopy and esophageal function testing, including esophageal manometry and pH testing.

By applying current guideline-based management—emphasizing stepwise therapy, periodic reassessment, and judicious investigation—primary care clinicians can manage gastroesophageal reflux disease confidently and reduce unnecessary referrals, and thus optimize both patient outcomes and health care resource use.

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

[15] [15] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [15]. |

1. Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, et al. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: A meta-analysis. Gut 2018;67:430-440. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589 [16].

2. Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, et al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: A global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:1900-1920. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x [17].

3. Argüero J, Sifrim D. Pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: Implications for diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024;21:282-293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00883-z [18].

4. Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, et al. ACG clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117:27-56. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538 [19].

5. Gyawali CP, Yadlapati R, Fass R, et al. Updates to the modern diagnosis of GERD: Lyon consensus 2.0. Gut 2024;73:361-371. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330616 [20].

6. Souza RF, Spechler SJ. Mechanisms and pathophysiology of Barrett oesophagus. Nat Rev Gastro-enterol Hepatol 2022;19:605-620. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00622-w [21].

7. Killcoyne S, Fitzgerald RC. Evolution and progression of Barrett’s oesophagus to oesophageal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2021;21:731-741. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-021-00400-x [22].

8. Kahrilas PJ, Altman KW, Chang AB, et al. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux in adults: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016;150:1341-1360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1458 [23].

9. Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: Clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut 1999;45:172-180. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.45.2.172 [24].

10. Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus: An updated ACG guideline. Am J Gastroenterol 2022;117:559-587. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680 [25].

11. Ness-Jensen E, Hveem K, El-Serag H, Lagergren J. Lifestyle intervention in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:175-182.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.176 [26].

12. Chen Y, Sun C, Wu Y, et al. Do proton pump inhibitors prevent Barrett’s esophagus progression to high-grade dysplasia and esophageal adenocarcinoma? An updated meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2021;147:2681-2691. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03544-3 [27].

13. Jankowski JAZ, de Caestecker J, Love SB, et al. Esomeprazole and aspirin in Barrett’s oesophagus (AspECT): A randomised factorial trial. Lancet 2018;392(10145):400-408. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31388-6 [28].

14. Iwakiri K, Fujiwara Y, Manabe N, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease 2021. J Gastroenterol 2022;57:267-285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-022-01861-z [29].

15. Lima JJ, Thomas CD, Barbarino J, et al. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for CYP2C19 and proton pump inhibitor dosing. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2021;109:1417-1423. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2015 [30].

16. Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019;157:682-691.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056 [31].

17. Deshpande A, Pant C, Pasupuleti V, et al. Association between proton pump inhibitor therapy and Clostridium difficile infection in a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:225-233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.030 [32].

18. Spence RW, Celestin LR. Gynaecomastia associated with cimetidine. Gut 1979;20:154-157. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.20.2.154 [33].

19. Leiman DA, Riff BP, Morgan S, et al. Alginate therapy is effective treatment for GERD symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dow020 [34].

20. Salusky IB, Foley J, Nelson P, Goodman WG. Aluminum accumulation during treatment with aluminum hydroxide and dialysis in children and young adults with chronic renal disease. N Engl J Med 1991;324:527-531. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199102213240804 [35].

21. Food and Drug Administration. Metoclopramide (Reglan) label—boxed warning for tardive dyskinesia and 12-week duration limit. FDA Safety Labeling Update. 2011. Accessed 13 September 2025. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/017854s058lbl.pdf [36].

22. Cowan A, Garg AX, McArthur E, et al. Cardiovascular safety of metoclopramide compared to domperidone: A population-based cohort study. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2020;4:e110-e119. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcag/gwaa041 [37].

23. Food and Drug Administration. Voquezna triple/dual pak (vonoprazan) prescribing information. FDA Drug Database. 2022. Accessed 13 September 2025. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215152s000,215153s000lbl.pdf [38].

24. Laine L, Spechler S, Yadlapati R, et al. Vonoprazan is efficacious for treatment of heartburn in non-erosive reflux disease: A randomized trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024;22:2211-2220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2024.05.004 [39].

Dr Nap Hill is a gastroenterology fellow in the Division of Gastroenterology, University of British Columbia, at Vancouver General Hospital. Dr Kalra is an internal medicine resident at UBC. Dr Moosavi is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Medicine, UBC, and a staff gastroenterologist at Vancouver General Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Sarvee Moosavi, sarvee.moosavi@gmail.com [40].

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/node/7824

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/estello-nap-hill-md-frcpc

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/gunisha-kalra-md

[4] https://bcmj.org/author/sarvee-moosavi-md-frcpc-edm-agaf

[5] https://bcmj.org/print/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting

[6] https://bcmj.org/printmail/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting

[7] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[8] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Diagnosis and management in a primary care setting&url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[9] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[10] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[11] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_GERD_Figure1.jpg

[12] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_GERD_Table.jpg

[13] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_GERD_Figure2.jpg

[14] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_GERD_Figure3.jpg

[15] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[16] https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589

[17] https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00630.x

[18] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-023-00883-z

[19] https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001538

[20] https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330616

[21] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-022-00622-w

[22] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-021-00400-x

[23] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1458

[24] https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.45.2.172

[25] https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000001680

[26] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.04.176

[27] https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-021-03544-3

[28] https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31388-6

[29] https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-022-01861-z

[30] https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.2015

[31] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056

[32] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.030

[33] https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.20.2.154

[34] https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dow020

[35] https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199102213240804

[36] http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/017854s058lbl.pdf

[37] https://doi.org/10.1093/jcag/gwaa041

[38] http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/215152s000,215153s000lbl.pdf

[39] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2024.05.004

[40] mailto:sarvee.moosavi@gmail.com

[41] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176?arturl=/articles/gastroesophageal-reflux-disease-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&nodeid=67

[42] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop