ABSTRACT: Functional dyspepsia is a common condition that involves a complex of symptoms, such as epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, and/or early satiety. While the pathophysiology is not completely understood, it is likely a complex interplay between the gut–brain axis, gut microbiome, and motor and sensory functions of the gastrointestinal tract. Endoscopy is not a mainstay of diagnostic testing and should be reserved for patients who are 60 years of age or older, or for high-risk patients based on individual cases. Clinical diagnosis can be made using the Rome IV criteria. Dietary modifications should be considered as first-line therapy prior to the use of pharmacological therapies. Other nonpharmacological treatments, such as exercise, psychological therapies, and patient counseling, should also be considered. Pharmacological treatments involve the use of proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, and neuromodulators. Management may also require a multidisciplinary approach that includes dietitians and psychologists.

Management of functional dyspepsia requires a multipronged approach, including nonpharmacological lifestyle changes, pharmacological therapies with a stepwise approach, and a multidisciplinary approach with dietitians and psychologists.

Functional dyspepsia is a chronic, complex constellation of symptoms that include epigastric pain or burning, postprandial fullness, and/or early satiety. Given the spectrum of symptoms, it is a common presenting complaint in primary care; the estimated prevalence is 8% in Canada and 20% globally.[1,2] In addition to its burden on quality of life, functional dyspepsia is associated with significant health care costs: the annual economic impact is estimated at $18 billion in the United States alone.[3] Symptom overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, gastroparesis, and peptic ulcer disease, leading to misdiagnosis, unnecessary investigations, patient frustration, and significant impact on quality of life.[4] Given that functional dyspepsia affects almost 1 in every 12 Canadians,[1,2] primary care providers are uniquely positioned to diagnose and manage it effectively. Our aim is to provide a structured clinical pathway for diagnosing and managing functional dyspepsia in the primary care setting, which will allow family physicians to build on their expertise to both optimize patient outcomes and eliminate unnecessary wait times and testing.

Mohammad is a 51-year-old man who has had ongoing abdominal pain for several years. His medical history includes dyslipidemia on statin therapy and generalized anxiety disorder not on medical therapy. He experiences epigastric and right upper quadrant pain three to four times per week in both fasting and unfasting states, with no clear food triggers. He has no personal or family history of gastrointestinal disease and no weight loss; however, during these pain episodes, he often takes time off work. His physical examination suggests no abnormalities. He has been on proton pump inhibitor therapy with escalating doses to twice daily, and he has cut out acidic foods, caffeine, and wine, with no effect. What should the next steps be in the management of his condition?

Samantha is a 43-year-old woman who experiences chronic postprandial fullness with bloating and discomfort on most days. This is often associated with nausea, and less frequently with vomiting. Her medical history includes hypothyroidism, which is well managed on levothyroxine, and fibromyalgia, for which she takes gabapentin. Due to abdominal pain, she has been started on hydromorphone as needed. Her physical examination shows a mildly distended abdomen with mild left-side discomfort. She has tried proton pump inhibitor therapy with no effect. What should the next steps be in the management of her condition?

Due to the multifaceted nature of functional dyspepsia, its pathophysiology is complex and not yet fully understood. A number of potential mechanisms have been proposed; functional dyspepsia is likely a result of a complex interplay between them.

The gut–brain axis, communicated via the hypothalamic–pituitary axis, is modulated by stress, immune function, and the gut microbiome.[5] Central signaling through corticotropin affects gut permeability, with eosinophilic and mast cell activation contributing to barrier dysfunction.[5,6] Adverse early life experiences can also contribute to functional gut disorders,[7] which underscores the gut–brain relationship.

Increased duodenal bacterial load is correlated with meal-related symptoms and thus links the small-intestine microbiome with dyspeptic symptoms.[8] Dysbiosis also alters the composition of bile acids, which promotes pro-inflammatory bacterial overgrowth.[9] This relationship between the microbiome and dyspepsia is underscored by the postgastroenteritis dyspepsia phenomenon[10] and the effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication in resolving dyspeptic symptoms.[8]

Low-grade duodenal inflammation, evidenced by abnormal populations of inflammatory cells in duodenal samples of functional dyspepsia patients,[11] impairs duodenal mucosa integrity,[11] which leads to delayed gastric emptying[12] and decreased neuronal responsiveness,[13] and thus disrupts gastrointestinal neuroregulation.[5]

While poor gastric emptying was thought to be directly correlated with dyspepsia, associations between functional dyspepsia and gastric emptying are inconsistent.[14] Pasricha and colleagues showed that functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis are clinically and pathologically indistinguishable in tertiary centres, which suggests they represent a spectrum of gastric neuromuscular disorders.[15] Additionally, visceral hypersensitivity, modulated by mechanical inputs, receptors, and enteral hormones,[16,17] contributes to epigastric pain and is associated with nonpainful symptoms of fullness, bloating, and belching.[16-18]

Risk factors for functional dyspepsia include female sex, smoking, use of NSAIDs, H. pylori infection,[1] acute gastroenteritis,[19] and psychiatric comorbidities such as anxiety and depression.[20]

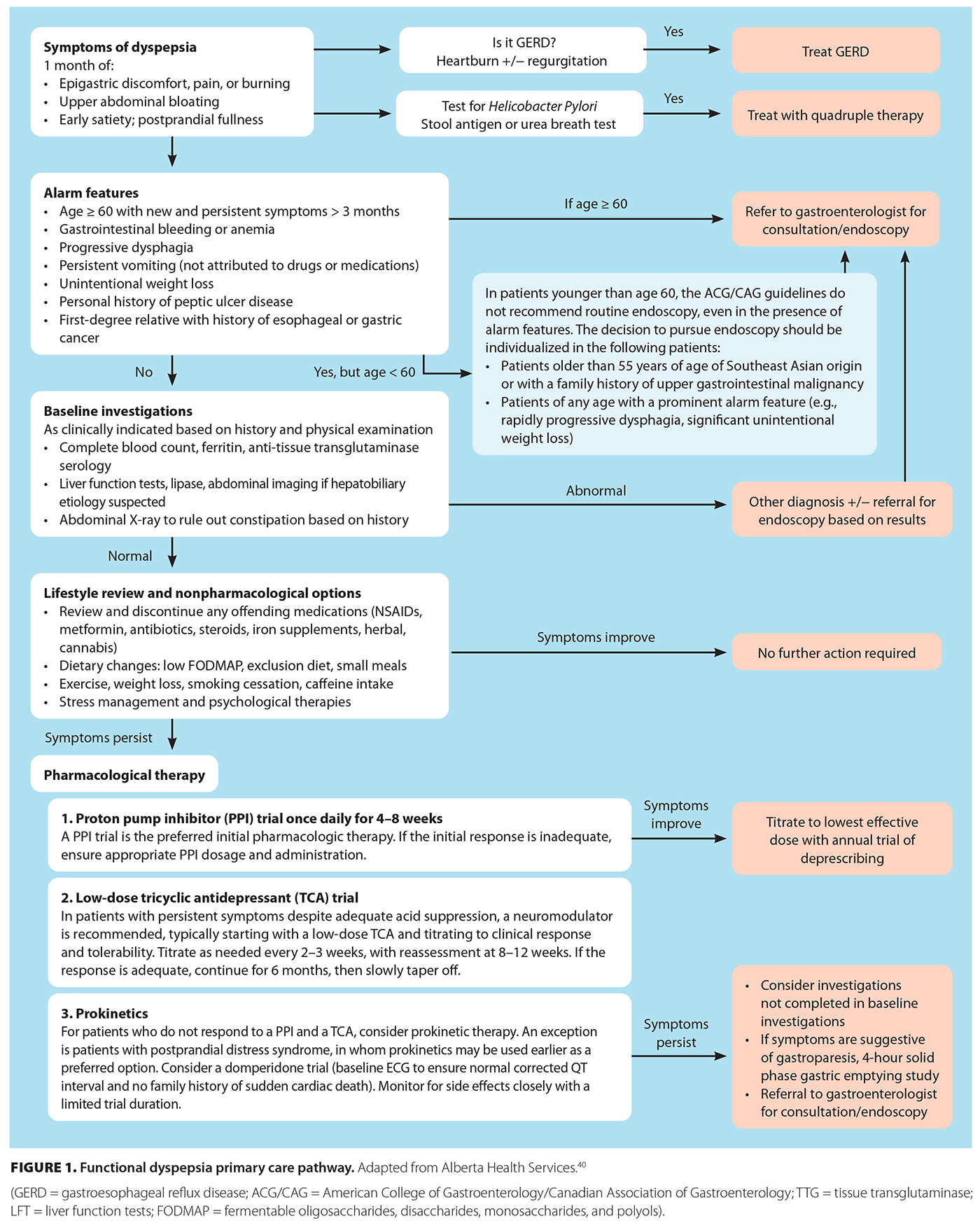

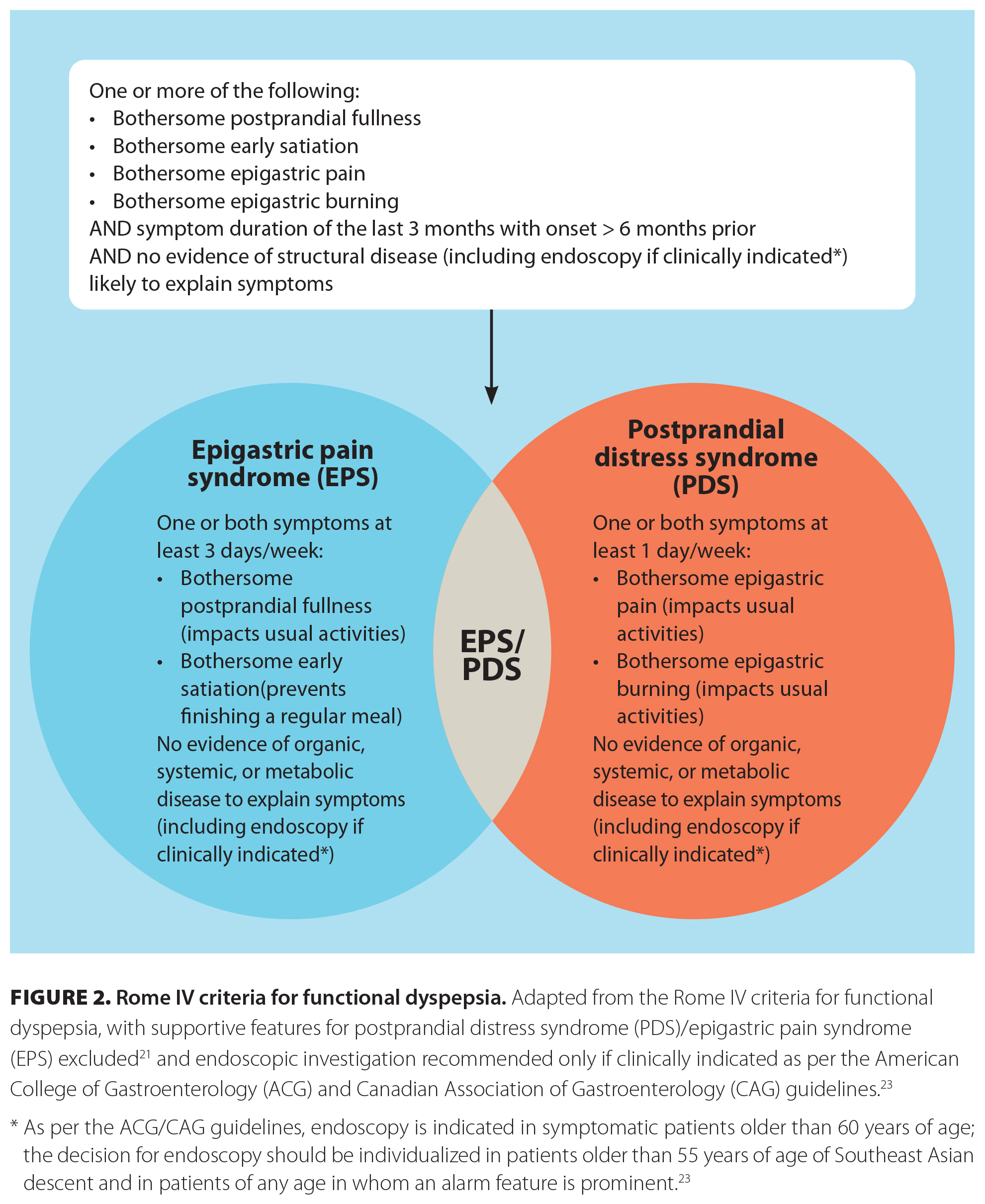

[11]Functional dyspepsia should be considered in patients who present with symptoms of postprandial fullness, early satiety, bloating, and/or epigastric pain or burning in the absence of alarm features [Figure 1 [11]].[21] Epigastric burning in particular should be further characterized in terms of location, timing, and modifying factors, because it is often confused with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Recurrent or cyclic vomiting or symptoms related to defecation suggest alternative diagnoses and warrant appropriate workup, although other gut–brain interaction disorders could coexist. Once functional dyspepsia is suspected, diagnosis requires a detailed history and, in appropriate patients, can be made clinically using Rome IV criteria [Figure 2 [12]],[21] which will minimize the use of generally low-yield endoscopy and delays in care.

[11]Functional dyspepsia should be considered in patients who present with symptoms of postprandial fullness, early satiety, bloating, and/or epigastric pain or burning in the absence of alarm features [Figure 1 [11]].[21] Epigastric burning in particular should be further characterized in terms of location, timing, and modifying factors, because it is often confused with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Recurrent or cyclic vomiting or symptoms related to defecation suggest alternative diagnoses and warrant appropriate workup, although other gut–brain interaction disorders could coexist. Once functional dyspepsia is suspected, diagnosis requires a detailed history and, in appropriate patients, can be made clinically using Rome IV criteria [Figure 2 [12]],[21] which will minimize the use of generally low-yield endoscopy and delays in care.

Rome IV criteria for the diagnosis of functional dyspepsia include one or more of bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning; symptom duration of the past 3 months, with onset 6 months prior to diagnosis; and no evidence of structural disease as an alternative etiology.[21] Once functional dyspepsia has been diagnosed, it can be further classified into two subtypes: postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome.[21] The former is characterized by bothersome postprandial fullness and/or early satiation at least 3 days per week; the latter is characterized by bothersome epigastric pain or burning at least 1 day per week [Figure 2 [12]].[21] In certain patients, the two subtypes may overlap.[22] Determining subtypes may be beneficial in management.

[12]As per the American College of Gastroenterology and Canadian Association of Gastroenterology guidelines, endoscopy is not routinely required to diagnose functional dyspepsia and should be reserved for specific patient populations: symptomatic patients older than 60 years of age, with a lower threshold of 55 years of age in patients from Southeast Asia, given the higher prevalence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy in that population [Figure 1 [11]].[23] In patients who are younger than 60 years of age, routine endoscopy is not recommended, even in the presence of alarm features [Figure 1 [11]].[23] However, in patients from Southeast Asia who have a family history of upper gastrointestinal malignancy or a prominent alarm feature (e.g., rapidly progressive dysphagia, significant unintentional weight loss), the decision to use endoscopy should be individualized.[23]

[12]As per the American College of Gastroenterology and Canadian Association of Gastroenterology guidelines, endoscopy is not routinely required to diagnose functional dyspepsia and should be reserved for specific patient populations: symptomatic patients older than 60 years of age, with a lower threshold of 55 years of age in patients from Southeast Asia, given the higher prevalence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy in that population [Figure 1 [11]].[23] In patients who are younger than 60 years of age, routine endoscopy is not recommended, even in the presence of alarm features [Figure 1 [11]].[23] However, in patients from Southeast Asia who have a family history of upper gastrointestinal malignancy or a prominent alarm feature (e.g., rapidly progressive dysphagia, significant unintentional weight loss), the decision to use endoscopy should be individualized.[23]

Aside from endoscopy, diagnostics for functional dyspepsia are limited. All patients should undergo H. pylori testing, via either gastric biopsies during endoscopy for patients 60 years of age or older or noninvasive testing for patients younger than 60 years of age, with treatment and confirmation of eradication.[23] It is also prudent to rule out celiac disease by ordering anti–tissue transglutaminase serology. In patients with predominant symptoms of nausea and vomiting or significant early satiety and postprandial fullness refractory to therapy, gastroparesis should be considered.[24] To establish the diagnosis, a 4-hour solid phase gastric emptying study is recommended; however, upper endoscopy should be performed first to rule out structural causes.[24] The use of 2-hour studies is discouraged due to false negatives.[24]

The American College of Gastroenterology and Canadian Association of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend noninvasive H. pylori testing in patients younger than 60 years of age who have dyspepsia, because it is a cost-effective strategy that minimizes unnecessary endoscopy[25] and reduces gastric cancer rates in Asian populations.[26] In patients who do not undergo endoscopic evaluation, noninvasive testing with the urea breath test or stool antigen testing is preferred;[27] the choice of modality is contingent upon local resource availability and patient preference. Serologic testing has lower specificity for acute infection and thus is not preferred. Patients should be off proton pump inhibitor therapy for 2 weeks prior to testing. If testing is positive for H. pylori, patients should be treated with quadruple therapy, and a confirmation of eradication test should be conducted after treatment.[25] We refer readers to the American College of Gastroenterology guideline for H. pylori treatment recommendations and pharmacotherapy regimens,[25] because this is outside the scope of this article.

The approach to managing functional dyspepsia is multipronged and may involve nonpharmacological interventions, pharmacological treatments, and alternative pharmacologic therapies. A stepwise approach is required [Figure 1 [11]], often with the involvement of dietitians and psychologists.

Diet and exercise: Managing functional dyspepsia through dietary modifications should be considered first-line therapy prior to the use of pharmacological treatments. Patients whose diets are low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAP) show symptomatic improvement, particularly those with postprandial distress syndrome.[28] Similarly, patients who follow a Mediterranean diet have shown an associated decrease in dyspeptic symptoms.[29] Conversely, alcohol, coffee, spicy food, and gluten are common triggers for functional dyspepsia[29] and, depending on individual patient response, should be avoided. Although the data are primarily from observational studies, small meals, low-FODMAP diets, and avoidance of trigger foods are generally recommended, and specific dietary choices (e.g., gluten-free, Mediterranean) should be individualized.[28,29]

Systematic reviews that evaluated the effectiveness of exercise—from aerobic exercise or walking to traditional Chinese exercises—found improvements in symptoms of epigastric fullness and pain, enhanced quality of life and sleep, and reduction in depressive symptoms;[30] however, many studies included concurrent pharmacological or psychological interventions.[30] Thus, while the benefit of exercise alone remains unclear, given the lack of harm, it is a reasonable first-line lifestyle intervention.

Other: Before initiating pharmacological interventions, the patient’s medications and any associated side effects should be carefully reviewed. Medications commonly associated with functional dyspepsia symptoms, such as NSAIDs, steroids, metformin, glucagon-like peptide-1 agonists, antibiotics, and opioids, should be discontinued.[5] Recreational drug use, specifically cannabis, should be reviewed and discouraged. There is a lack of evidence that smoking cessation, weight management, and alcohol cessation improve functional dyspepsia symptoms, but they are important general health measures.

Psychological therapies: While pharmacological therapies are the mainstay of treatment, a significant portion of patients may benefit from psychological therapy, given the coexisting mental health disorders.[23] While systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials have shown statistically significant benefits of psychological therapies,[31] including cognitive-behavioral therapy, meditation, gut-directed hypnosis, and relaxation therapy, the quality of the data is very low due to study heterogeneity, methodological limitations, and study bias.[23]

Acid suppression therapy: Given the presence of abnormal inflammatory cells, the immune response in the duodenum,[11] and hypersensitivity to gastric acid, acid suppression therapy is a recommended first-line treatment in functional dyspepsia.[25] While the use of proton pump inhibitors is preferred,[23] histamine-2 receptor antagonists are reasonable alternatives if proton pump inhibitors are not tolerated or are ineffective; however, evidence suggesting their equal efficacy is limited by trial heterogeneity and misclassification of diagnoses.[23] Proton pump inhibitor dosing is recommended as once daily; further escalation is unlikely to confer benefit in the functional dyspepsia population.[23] Response should be reassessed in 8 weeks, and attempts to taper off or discontinue proton pump inhibitor therapy should be made every 6 to 12 months.[23]

Neuromodulators: In patients who do not respond to proton pump inhibitors or achieve only partial response, the use of neuromodulators is recommended.[23] Specific therapies include tricyclic antidepressants, which are preferred as first-line therapy, and mirtazapine.[23] Patients should be started at the lowest dose. The dose should be titrated up every 2 to 3 weeks as needed, then reassessed at 8 to 12 weeks.[32] If efficacious, tricyclic antidepressants should be continued for 6 months, then slowly tapered off; they can be re-initiated in recurrent dyspepsia at the previous lowest effective dose.[32] In patients who cannot tolerate tricyclic antidepressants or have concurrent weight loss, mirtazapine may improve both symptoms and early satiety.[23] Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have not shown any benefit, and there is currently no role for them in functional dyspepsia.[33]

Prokinetics: In cases where the above therapies have failed, prokinetic agents, such as metoclopramide and domperidone, are third-line options, but there is limited improvement in quality of life.[34] Consideration could be given to using prokinetic agents as first-line therapy in patients with postprandial distress syndrome subtype. Notably, prokinetic agents, particularly metoclopramide, have significant adverse effects, such as tardive dyskinesia, which affects up to 30% of patients.[23] Therefore, trial use with limited duration and close monitoring are advised. We recommend a baseline corrected QT interval prior to initiating therapy; cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death have been reported with the use of domperidone. Additional agents, such as buspirone, a 5-HT1A receptor agonist that causes fundal relaxation, have not shown significant improvement in dyspeptic symptoms and only modest improvement in bloating severity and early satiety;[35] however, they could be considered in patients with predominant postprandial distress syndrome subtype that have failed to respond to other therapies.

Other: Other pharmacological therapies, including gabapentin and rifaximin, as well as nonpharmacological therapies such as FDgard, a duodenal-release caraway oil/menthol formulation commonly used to treat irritable bowel syndrome, have shown some benefit in single trials or retrospective case series;[36-38] however, further study is needed before definitive conclusions can be drawn, and they are not currently recommended for the management of functional dyspepsia. Herbal medications, such as rikkunshito, artichoke leaf extract, and Zhizhu Kuanzhong, have been used traditionally to treat upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Symptomatic improvement has been demonstrated in controlled trials and systematic reviews, but concerns remain regarding toxicity, quality control, and dosage regulation; thus, there are no current recommendations for the use of these herbal medications in functional dyspepsia management.[39]

Patients would benefit from counseling and validation from their providers, given that symptoms may be dismissed in the absence of structural disease. Patients should be counseled that functional dyspepsia is a common condition that causes pain, discomfort, or a feeling of fullness in the upper belly, and they can feel bloated, full quickly, and nauseated. This does not mean there is something structurally wrong with their stomach or intestines. Rather, due to the complexity of the gastrointestinal tract nervous system, visceral hypersensitivity and interplay of the gut microbiome, and the gut–brain interaction, patients may experience dyspeptic symptoms. Their symptoms can also be due to infection, such as by H. pylori, and can be exacerbated by medications such as NSAIDs. Emotional and psychological cofactors such as anxiety and depression may also play a large role in symptomatology. Finally, diet can also play a role in symptom manifestation. Treatment includes dietary changes, regular exercise, and managing concurrent mental health disorders and may require a multidisciplinary approach with a dietitian and psychologist. Treatment with medications includes acid reflux medications to calm down the lining of the gut, anti-depressant medications that help regulate the gut–brain interaction, and prokinetics that stimulate gastric emptying. Opioids should be avoided as they carry risk of dependence, tolerance, and can further lead to narcotic bowel syndrome; they have no role in the management of functional dyspepsia. Management of functional dyspepsia may require trial of various therapeutic options, as what works for one person may not work for another, but with the right care, most people with functional dyspepsia can manage their symptoms successfully.

Mohammad was misdiagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux disease and thus is nonresponsive to escalating doses of proton pump inhibitors. The lack of food triggers, association with meal times or positional changes, and localization to epigastric pain rather than typical retrosternal heartburn symptoms, point away from gastroesophageal reflux disease. He meets Rome IV criteria for epigastric pain syndrome. Given his age, lack of alarm features, chronicity, and stability of symptoms, he does not require urgent upper endoscopy; a clinical diagnosis of functional dyspepsia can be made. He should be offered noninvasive H. pylori testing and treatment. If he is treated and his symptoms persist or the H. pylori test is negative, given his lack of response to proton pump inhibitor therapy, he should be started on low-dose tricyclic antidepressant therapy, such as amitriptyline, 10 to 15 mg by mouth every bedtime, or nortriptyline, 10 to 25 mg by mouth every bedtime, with reassessment at 8 to 12 weeks.

Samantha meets Rome IV criteria for functional dyspepsia, favored postprandial distress syndrome. Given her abdominal exam and opioid use, an abdominal X-ray is performed, which shows constipation. She is treated with osmotic laxative polyethylene glycol. While this mildly improves her symptoms, her quality of life remains impaired. She is counseled on tapering off her opioids to avoid dependence and narcotic bowel and is started on tricyclic antidepressant therapy with nortriptyline, 10 mg by mouth every bedtime for 12 weeks, but shows little improvement. Given her intermittent nausea and vomiting, an upper endoscopy and 4-hour gastric emptying study (off opioids) are performed, which show mild delayed gastric emptying with 15% retention of a standardized meal at 4 hours. She is then started on domperidone, 10 mg by mouth three times a day, 30 minutes before meals, which significantly improves her symptoms. She is counseled on following a low-fibre, low-fat diet (gastroparesis diet) and is referred to a dietitian for further diet optimization. Her dose will be reassessed in 2 months.

In patients with functional dyspepsia, it is important to test for and treat H. pylori. Dietary modifications should be considered first-line therapy prior to the use of pharmacological treatments. However, the use of acid reflux medications can help by calming the lining of the gut. If the patient receives no relief, medications such as tricyclic antidepressants, which help regulate the gut–brain interaction and visceral hypersensitivity, should be considered. If symptoms are mainly postprandial bloating fullness, prokinetics that stimulate gastric emptying may be considered as first-line therapy. The use of opioids should be avoided because they are associated with the risk of tolerance and dependence and can further lead to narcotic bowel syndrome. They have no role in the management of functional dyspepsia. Various therapeutic options may be needed to manage functional dyspepsia, because what works for one patient may not work for another, but with the right care, most patients can manage their symptoms successfully. In addition, management may require a multidisciplinary approach that includes dietitians and psychologists.

None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

[13] [13] |

| This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License [13]. |

1. Ford AC, Marwaha A, Sood R, Moayyedi P. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, uninvestigated dyspepsia: A meta-analysis. Gut 2015;64:1049-1057. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843 [14].

2. Aziz I, Palsson OS, Törnblom H, et al. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associations for symptom-based Rome IV functional dyspepsia in adults in the USA, Canada, and the UK: A cross-sectional population-based study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3:252-262. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30003-7 [15].

3. Lacy BE, Weiser KT, Kennedy AT, et al. Functional dyspepsia: The economic impact to patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:170-177. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12355 [16].

4. Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al. Initial poor quality of life and new onset of dyspepsia: Results from a longitudinal 10-year follow-up study. Gut 2007;56:321-327. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.099846 [17].

5. Ford AC, Mahadeva S, Carbone MF, et al. Functional dyspepsia. Lancet 2020;396(10263):1689-1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4 [18].

6. Rodiño-Janeiro BK, Alonso-Cotoner C, Pigrau M, et al. Role of corticotropin-releasing factor in gastrointestinal permeability. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2015;21:33-50. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm14084 [19].

7. Videlock EJ, Adeyemo M, Licudine A, et al. Childhood trauma is associated with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1954-1962. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.058 [20].

8. Zhong L, Shanahan ER, Raj A, et al. Dyspepsia and the microbiome: Time to focus on the small intestine. Gut 2017;66:1168-1169. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312574 [21].

9. Pavlidis P, Powell N, Vincent RP, et al. Systematic review: Bile acids and intestinal inflammation—Luminal aggressors or regulators of mucosal defence? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;42:802-817. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13333 [22].

10. Pike BL, Porter CK, Sorrell TJ, Riddle MS. Acute gastroenteritis and the risk of functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1558-1563. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ajg.2013.147 [23].

11. Vanheel H, Vicario M, Vanuytsel T, et al. Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut 2014;63:262-271. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303857 [24].

12. Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, et al. Small bowel homing T cells are associated with symptoms and delayed gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1089-1098. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.512 [25].

13. Cirillo C, Bessissow T, Desmet A-S, et al. Evidence for neuronal and structural changes in submucous ganglia of patients with functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1205-1215. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.158 [26].

14. Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Association of the predominant symptom with clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2006;130:296-303. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.019 [27].

15. Pasricha PJ, Grover M, Yates KP, et al. Functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis in tertiary care are interchangeable syndromes with common clinical and pathologic features. Gastroenterology 2021;160:2006-2017. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.230 [28].

16. Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Dupont P, et al. Abnormal regional brain activity during rest and (anticipated) gastric distension in functional dyspepsia and the role of anxiety: A H2[15]O-PET study. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:913-924. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.39 [29].

17. Tack J, Caenepeel P, Fischler B, et al. Symptoms associated with hypersensitivity to gastric distention in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 2001;121:526-535. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.27180 [30].

18. Vandenberghe J, Vos R, Persoons P, et al. Dyspeptic patients with visceral hypersensitivity: Sensitisation of pain specific or multimodal pathways? Gut 2005;54:914-919. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.052605 [31].

19. Futagami S, Itoh T, Sakamoto C. Systematic review with meta-analysis: Post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:177-188. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13006 [32].

20. Aro P, Talley NJ, Johansson S-E, et al. Anxiety is linked to new-onset dyspepsia in the Swedish population: A 10-year follow-up study. Gastroenterology 2015;148:928-937. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.039 [33].

21. Drossman DA, Hasler WL. Rome IV—Functional GI disorders: Disorders of gut–brain interaction. Gastroenterology 2016;150:1257-1261. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035 [34].

22. Carbone F, Holvoet L, Tack J. Rome III functional dyspepsia subdivision in PDS and EPS: Recognizing postprandial symptoms reduces overlap. Neuro-gastroenterol Motil 2015;27:1069-1074. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12585 [35].

23. Moayyedi PM, Lacy BE, Andrews CN, et al. ACG and CAG clinical guideline: Management of dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:988-1013. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.154 [36].

24. Staller K, Parkman HP, Greer KB, et al. AGA clinical practice guideline on management of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology 2025;169:828-861. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2025.08.004 [37].

25. Chey WD, Howden CW, Moss SF, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2024;119:1730-1753. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002968 [38].

26. Ford AC, Yuan Y, Forman D, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication for the prevention of gastric neoplasia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;7:CD005583. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005583.pub3 [39].

27. Malfertheiner P, Camargo MC, El-Omar E, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023;9:19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00431-8 [40].

28 Rettura F, Lambiase C, Grosso A, et al. Role of low-FODMAP diet in functional dyspepsia: “Why”, “when”, and “to whom.” Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2023;Feb-Mar:62-63:101831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2023.101831 [41].

29. Duboc H, Latrache S, Nebunu N, Coffin B. The role of diet in functional dyspepsia management. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00023 [42].

30. Huang Z, Zhuang Y, Lin T, et al. Efficacy of exercise therapies on functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Liver Dis 2025;57:2087-2098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2025.06.004 [43].

31. Soo S, Moayyedi P, Deeks J, et al. Psychological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(2):CD002301. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002301.pub4 [44].

32. Longstreth GF, Lacy BE. Functional dyspepsia in adults. UpToDate. Topic last updated 5 December 2025. Accessed 20 July 2025. www.uptodate.com/contents/functional-dyspepsia-in-adults [45].

33. Lu Y, Chen M, Huang Z, Tang C. Antidepressants in the treatment of functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One 2016;11:e0157798. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157798 [46].

34. Pittayanon R, Yuan Y, Bollegala NP, et al. Prokinetics for functional dyspepsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2019;114:233-243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0258-6 [47].

35. Mohamedali Z, Amarasinghe G, Hopkins CW, Moulton CD. Effect of buspirone on upper gastrointestinal disorders of gut–brain interaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2025;31:18-27. https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm24115 [48].

36. Tan VPY, Liu KSH, Lam FYF, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Rifaximin versus placebo for the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2017;45:767-776. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13945 [49].

37. Staller K, Thurler AH, Reynolds JS, et al. Gabapentin improves symptoms of functional dyspepsia in a retrospective, open-label cohort study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53:379-384. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001034 [50].

38. Chey WD, Lacy BE, Cash BD, et al. A novel, duodenal-release formulation of a combination of caraway oil and L-menthol for the treatment of functional dyspepsia: A randomized controlled trial. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2019;10:e00021. https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000021 [51].

39. Gwee K-A, Holtmann G, Tack J, et al. Herbal medicines in functional dyspepsia—Untapped opportunities not without risks. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2021;33:e14044. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14044 [52].

40. Alberta Health Services. Dyspepsia primary care pathway. Updated 2020. Accessed 17 November 2025. www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/arp/if-hp-arp-dh-dyspepsia-pathway-adult-gi.pdf [53].

Dr Kalra is an internal medicine resident at the University of British Columbia. Dr Nap Hill is a gastroenterology fellow in the Division of Gastroenterology, UBC, at Vancouver General Hospital. Dr Moosavi is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Medicine, UBC, and a staff gastroenterologist at Vancouver General Hospital.

Corresponding author: Dr Sarvee Moosavi, sarvee.moosavi@gmail.com [54].

Links

[1] https://bcmj.org/node/7824

[2] https://bcmj.org/author/gunisha-kalra-md

[3] https://bcmj.org/author/estello-nap-hill-md-frcpc

[4] https://bcmj.org/author/sarvee-moosavi-md-frcpc-edm-agaf

[5] https://bcmj.org/print/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting

[6] https://bcmj.org/printmail/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting

[7] http://www.facebook.com/share.php?u=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[8] https://twitter.com/intent/tweet?text=Functional dyspepsia: Diagnosis and management in a primary care setting&url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[9] https://www.linkedin.com/sharing/share-offsite/?url=https://bcmj.org/print/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton&via=BCMedicalJrnl&tw_p=tweetbutton

[10] https://bcmj.org/javascript%3A%3B

[11] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_dyspepsia_Figure1.jpg

[12] https://bcmj.org/sites/default/files/BCMJ_Vol68_No2_dyspepsia_Figure2.jpg

[13] http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

[14] https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307843

[15] https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30003-7

[16] https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.12355

[17] https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2006.099846

[18] https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30469-4

[19] https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm14084

[20] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.058

[21] https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312574

[22] https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13333

[23] https://doi.org/ 10.1038/ajg.2013.147

[24] https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303857

[25] https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.512

[26] https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2015.158

[27] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.019

[28] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2021.01.230

[29] https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2010.39

[30] https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.27180

[31] https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2004.052605

[32] https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13006

[33] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2015.01.039

[34] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.03.035

[35] https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.12585

[36] https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2017.154

[37] https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2025.08.004

[38] https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000002968

[39] https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005583.pub3

[40] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-023-00431-8

[41] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpg.2023.101831

[42] https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00023

[43] https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dld.2025.06.004

[44] https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002301.pub4

[45] http://www.uptodate.com/contents/functional-dyspepsia-in-adults

[46] https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157798

[47] https://doi.org/10.1038/s41395-018-0258-6

[48] https://doi.org/10.5056/jnm24115

[49] https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.13945

[50] https://doi.org/10.1097/MCG.0000000000001034

[51] https://doi.org/10.14309/ctg.0000000000000021

[52] https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14044

[53] http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/hp/arp/if-hp-arp-dh-dyspepsia-pathway-adult-gi.pdf

[54] mailto:sarvee.moosavi@gmail.com

[55] https://bcmj.org/modal_forms/nojs/webform/176?arturl=/articles/functional-dyspepsia-diagnosis-and-management-primary-care-setting&nodeid=67

[56] https://bcmj.org/%3Finline%3Dtrue%23citationpop